Bring back the public order lashings?

Sudan’s public order law used to dictate every aspect of people’s everyday lives. To many, especially women, it was an object of hate. Last year, wide-scale legal reforms repelled the law, but some argue that it is time to put it back in place. And the public order law’s most fierce advocates? The wealthy.

In December 2020, after a few days of protests in Al-Amarat, an upper-scale neighborhood in Khartoum, citizens organized a public event to discuss the main reason behind their protest movement and the way forward. For days, the community had been protesting against the rise of local coffee shops in the neighborhood and took to the streets to chant ‘no to janbat’ which is a colloquial term to describe humble, traditional and more reasonably priced coffee shops that often serve shisha, hot and cold drinks. Residents of Al-Amarat were arguing that the ‘janbat’ double up as venues for prostitution and drug use and distribution.

During the public event, a journalist stood up and explained that the current government allows this debauchery to take place. He argued that if the public order police had still been present on the streets, this chaos could never have happened.

Just a few days earlier, a viral video showed a young man interviewing young women about whether they think the public order police should resume operation. Most of the women interviewed said that they want the public order law to return. ‘There is too much freedom’, one of them said. We could argue that the show may have edited out opposing opinions and willfully features women who call for the public order police to return. If you do a YouTube search for public order in Arabic, several videos with provocative titles explain that this is what's happening after the public order police stopped its work: Videos range from young women and men dancing at a party to a female singer in a concert wearing what is viewed as “provocative”.

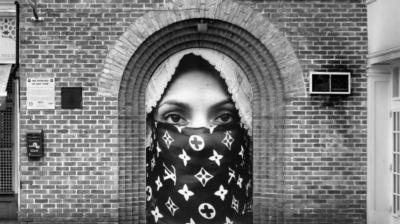

The Khartoum state public order law and the public order articles in the criminal law were known to discriminate against women and criminalize their dress-code and behaviour in private and public spaces. The public order articles, for example on indecent clothing and behaviour, continued to be used to control and intimidate women until the Minister of Justice repelled them in wide-scale legal reforms last year.

Since then, there has been continuous backlash.

In this commentary I argue that the recent reforms were not enough to dismantle the public order establishment. It continues to oppress women, but it has shifted its focus from upper-scale and middle-class neighborhoods to women in the informal sector, refugee and migrant women.

What is the public order establishment?

The public order or morality laws were built on an entire infrastructure from specialized courts to a designated police force spread out across the country. The laws were two-fold; the public order articles were part of the 1991 criminal act and there was also a separate 1996 Khartoum state public order law that was composed of 25 articles (other states also have state-level morality laws such as the famous “tazkyat al-muitmaa” law in Gedarif state). In the early 2010s, Bashir ordered the police to abandon the Khartoum state law after mounting international pressure. However, the police continued to take advantage of the criminal law to continue to persecute nearly 43,000 women a year as per the last known statistic. When the Islamists came to power through a military coup in 1989, they began implementing what they called the civilizational project. The public order was one the manifestations of this project which they described as a tool to “reformulate the Sudanese society on the bases of Islam”[1].

The Islamists used the public order as an important tool to sustain their power through building an environment of fear. This was harnessed by their empowerment of people to call and report any “suspicious” activities. The public order was transformed into a mentality that is widespread across the society. A citizen had the power to call on the public order if he saw girls dressed in “indecent clothing” or if he suspected that a mixed party was taking place in a private house. The law depended on loose articles with phrases such as “indecent clothing” to give its officers the chance to decide and rule out what is decent and indecent. Your safety and freedom was dependent on the opinion and personal preferences of public order officers and random men loitering on the street armed with a misogynistic vendetta.

The public order was transformed into a mentality that is widespread across the society.

For years, women groups advocated for the repeal of the public order establishment. Every week, a new high-profile case would send shockwaves in the community and make us feel threatened to leave the house. Once you were out in public, there was this constant distress mixed with fear as you watched your back and expected the police to arrest you at any time for wearing trousers or a skirt they deemed too tight or sitting with male friends in a park or getting a ride home with a male friend. All my friends, including myself, have encountered the public order police numerous times.

Xenophobia on the rise

Al-Amarat neighborhood which is both vast and home to many international organizations, embassies and companies has slowly changed in the past few decades. It has moved from being solely residential to a very commercial neighborhood. The same is happening in other parts of Khartoum South and East, but Al-Amarat is different with its out-dated infrastructure that translates into run-down streets and sewage water visible all year round. The Al-Amarat protests against the local coffee shops were stained by sentiments of everyday xenophobia. Residents as well as high-profile political and community leaders partly blamed ‘foreigners’ for all the ills spreading throughout the neighborhood. By ‘foreigners’, they mean Ethiopian migrants and Eritrean refugees who live in the surrounding neighborhoods and make up the majority of the workforce in coffee shops and other amenities. Xenophobia has been on the rise in Sudan for years, especially following the economic circumstances and its indisputable impact on peaceful coexistence. This was evident in the refusal of locals to allow South Sudanese, Eritrean and Ethiopian migrants and refugees in different parts of Khartoum to get cards to access subsidized bread even though the overwhelming majority are impoverished.

The Al-Amarat protests against the local coffee shops were stained by sentiments of everyday xenophobia.

The growing discourse by privileged Sudanese individuals calling for the return of the public order to “control” society misses out on two important points: Which society do they want to control? The first point is that the public order police never stopped working in the first place. They continue to terrorize people and especially women. Many activists have reported on how the public order crack down on women in the informal sector and migrant workers in the center and outskirts of Khartoum. They have also continued to crack down on informal alcohol sellers because the 2020 legal amendments have a clear loophole as they allow non-Muslims to consume alcohol, but ban Muslims from consuming and selling alcohol. Feminist activists in Sudan have highlighted how the law puts the seller at fault if she doesn’t ask her clients their religion before offering them her services, which is nothing short of ridiculous. The repeal of a handful of public order articles by the transitional government failed to understand the infrastructure that sets up the system as well as its impact on the society. For starters, this establishment is a multi-million dollar one. It used to bring funds to the state, and was a very good source of income for police officers. Infact, lenient judges who refused to impose hefty fines were often intimidated by police officers and were transferred to other police stations because funds were drying up.

The repeal of a handful of public order articles by the transitional government failed to understand the infrastructure that sets up the system as well as its impact on the society.

A lawyer stated to 3ayin, a Sudanese media outlet, that the number of public order courts rose after Sudan lost its oil revenues in 2011 following the independence of South Sudan and a survey showed that fines brought in “roughly 135 million Sudanese Pounds (roughly US$ 6,750,000) per year –almost as much as the entire Khartoum State health budget”. The survey only showed money that was made official. Most of the fines collected are received by officers before reaching the police station and many succumb to this blackmail as a desperate attempt to avoid any further humiliation. The public order establishment exhausted people financially, but helped thousands of officers thrive and sustain a lifestyle at the expense of women. In a work-visit to the women’s prison in Omdurman in 2014, I noted that 90% of prisoners were there on public order charges as per the prison records I had access to. The fight of this establishment to reclaim their former status - which gave them access to more funds as they blackmailed coffee-shop owners and clients in wealthier neighborhoods - will never stop.

The second important point is the fact that the wealthy who advocate for the return of the public order understand the system and have co-opted it to sustain a lifestyle knowing that their class and ethnic privilege, which is very much interconnected in Sudan, gives them a greater immunity than migrants and other Sudanese people in what they see as the periphery of the city.

Arrested for shisha? Pay the arresting officer before you reach the police station and you will sleep in your bed.

Anxious about public spaces? Invite your friends to your house and have a café deliver shishas to your doorstep and have alcohol delivered with a motorbike.

Arrested by the police? Call a lawyer and family friend and try to mitigate the situation.

This is not to say that young men and women in Al-Amarat, Khartoum two, Riyadh or elsewhere were not arrested before. Coffee shops were raided, parties and concerts were raided and women always found themselves singled out. Yet, the impact was not as extensive. How you are treated in the police station is based on class and ethnicity. Migrant women can face sexual abuse as well as extortion, and women who are poor and are from ethnic minorities make up the majority of the prison population because they lack the wealth and the social networks that protect them and lessens the repercussions.

How you are treated in the police station is based on class and ethnicity.

The public order has become a mentality. And a mentality is even harder to mitigate than the law. To bring about true change will take time and sustained efforts in improving school curriculums and countering fundmentalist propaganda. Moreover, more legal reforms are needed to improve the 2020 reforms and also fully tackle the remaining public order and the discriminatory articles that continue to govern the lives of the Sudanese. Meanwhile, the people in wealthier neighborhoods need to understand that the city is crumbling under pressures due to mass urbanization, lack of urban planning and lack of investment in infrastructure. Drugs are an increasing problem. Anyone living in Khartoum knows that. But we cannot limit the discourse on drug distribution to xenophobic rants about migrants and women in the informal sector. We need to talk openly about how the drug business is largely controlled by businessmen and military officers, and how it overwhelmingly impacts certain demographics more than others.

This Sudan blog post is written by Reem Abbas, a freelance journalist, writer, researcher and communications professional. She tweets using @ReemWrites

The views expressed in this post are those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the ARUS project or CMI.

[1] Salah, Walaa (2017). Dancing to the melodies of whips: the Implications of Sudan’s Sharia Laws on Art and Media .Master’s thesis, University of Essex.