The spatial governance of the Syrian refugee crisis in Jordan: Refugees between urban settlements and encampment policies

Jordan’s Syrian refugee crisis in a dynamic of governance

Reasserting the encampment governance of the Syrian refugee crisis

Governance toward urban settlements

Refugee urban settlements facilitated by jobs, investments, and citizenships

This CMI Report presents a critical analysis of the Jordans’ governance of the Syrian refugee crisis and discusses the spatial policies in the framework of space and power. It identifies a shift in the direction of governance and explores how settlement options between urban settings and refugee camps were shaped by policies and humanitarian aid.

About the authors

Zaid Awamleh

Zaid is a Humanitarian Architect specializing in the psychology of space. He is a CNRS research engineer who served as Jordan response person for the Migration Governance and Asylum Crisis program (MAGYC) and lead the team of the digital data content. Simultaneously, he is the Co-Founder and Vice-Chairman of SAIB Humanitarian NGO in addition to holding the positions of the project manager of a rehabilitation program with the UNDP. His work focuses on developing behavioral change methodologies relating to sense and placemaking, resilience, and gender roles with vulnerable communities and refugees. Zaid is a Ph.D. candidate at Leeds Beckett University in the UK, holds a Master’s degree in the field of Environment-Behavior sciences from IEU, and a Bachelor of Architecture and Interior Architecture from the German Jordanian University. Email: zaid.awamleh@live.com

Kamel Dorai

Kamel Doraï is a researcher at the French National Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) based at Migrinter, University of Poitiers (France) and was Director of the Department of contemporary studies at the French Institute for the Near East - Ifpo (Lebanon). His work focuses mainly on asylum and refugees in the Middle East. He has published several articles and book chapters on Palestinian and Syrian refugee camps in Jordan and Lebanon and urban refugees in Syria and Lebanon.

About this publication

This publication is a part of the project Urban Displacement, Development and Donor Policies in the Middle East (URBAN3DP).

Syrian refugees in Jordan

Jordan, a country of 10 million people with limited resources and a challenging economic situation, is home to the second-highest ratio of refugees in the world. Given that it is surrounded by a region that is frequently plagued by political unrest, its strategic location in the Middle East and its political stability and safety make it a sought-after place to seek refuge.

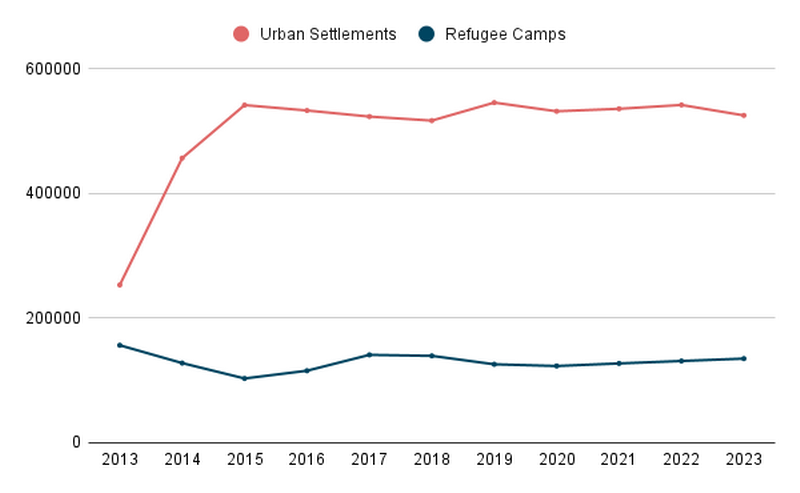

Disseminated between 15 official refugee camps and urban settlements, Jordan is hosting refugees from 57 different nationalities, mainly from Palestine, Iraq, Sudan, Somalia, Yemen, and Libya. Additionally, Jordan has hosted the third-largest population of Syrian refugees in the world since the beginning of the conflict in Syria in 2011. Out of the 1.3 million Syrian refugees according to the latest Jordanian Census (December 2015), the UNHCR registered a total of 661,854 refugees by the first quarter of 2023. Nearly 20% of the registered refugees are hosted in five official refugee camps across the country, while 80% are settled in urban areas (see Figure 1). Registered refugees were given temporary residence permits good for six months as a result of an agreement (Memorandum of Understanding) reached between the Jordanian government and UNHCR, as Jordan is not part of the 1951 Refugee Convention or the 1967 Protocol.

Jordan’s Syrian refugee crisis in a dynamic of governance

Managing the Syrian refugee influx in Jordan has witnessed serious shifts. The transition from the traditional governance of a refugee crisis to a response that is allegedly beneficial to both the host communities and refugees can be seen in a number of decisions and policies that identify the governance of the Syrian refugee crisis in Jordan. The former is typically framed into encampment policies with the provision of necessary aid and substances for a large influx of refugees, whereas the latter is based on an integration strategy that strives to include the needs of both refugees and the host communities in development agendas, mobilize additional development funding, and enhance burden sharing with nations that are hosting sizable refugee populations.

In Jordan, the UNHCR plays a significant role in governance when it comes to issues involving refugees. The Jordanian government and UNHCR have been collaborating closely to manage and organize the hosting of refugees in the country and to provide them with the services they require. The shift in governance necessitated the establishment of more relationships besides the UNHCR with national and international humanitarian organizations, as well as the public and private sectors.

Research Parameters

This CMI Report deduces that the demographics of the Syrian refugee settlements between the camps and the urban cities have been shaped by a shift in the governance strategies and agendas of the refugee crisis. The paper questions the spatial policies that shaped the settlement choices for the Syrian refugees in Jordan, what these spaces look like, and how they were subsequently utilized for aid, development, and control.

The author examined the decisions and policies that identify Jordan’s Syrian refugee governace in chronological order and accumulated them into two sections. The first are the decisions and policies that led to encampment, while the second refers to what promoted urban settlements.

Governance toward encampment

Decisions and policies that promoted encampment:

- Opening four new refugee camps in different cities in Jordan.

- Establishing the Syrian Refugee Camps Directorate (SRCD).

- Empowering and funding aid programs operating only inside refugee camps, not outside.

- Restricting camp residents’ movement to neighboring urban cities.

The opening of four refugee camps in different cities in Jordan was the first step that shaped the encampment policies in Jordan. The first residents of the Zaatari refugee camp, which opened on July 28, 2012, were a group of 450 Syrians who crossed the border into neighboring Jordan. With just a few tents, the camp quickly grew to be one of the largest Syrian refugee camps in the world, hosting 80,434 Syrian refugees in prefabricated metal shelters that served as schools, hospitals, and shops, while 26,000 shelters were designated for housing according to the most recent report by the UNHCR in 2022.

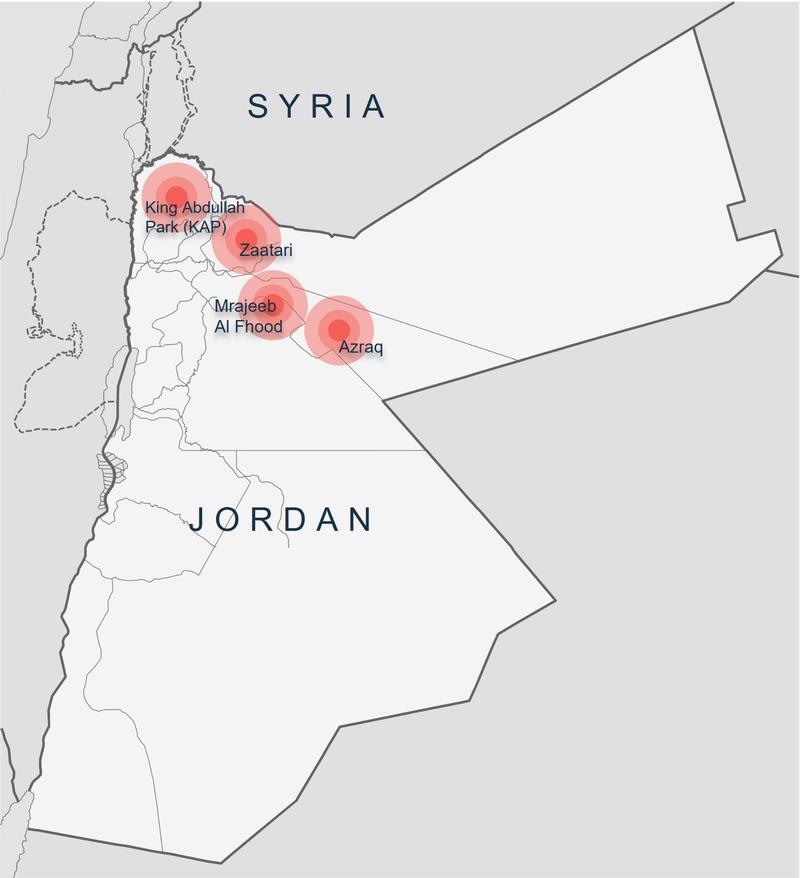

Syrian refugees in Jordan were hosted in four refugee camps in different cities, as shown in Figure 2.

- Zaatari refugee camp.

- King Abdullah Park (KAP)

- Mrajeeb Al Fhood Refugee Camp

- Azraq refugee camp

Figure 2: The locations of the four refugee camps in Jordan where Syrian refugees were hosted.

Source: Zaid Awamleh based on UNHCR data and Google Earth.

After the Zaatari camp, Jordan established the King Abdullah Park (KAP) refugee camp in 2012, and the UAE sponsored the establishment of the Mrajeeb Al Fhood Refugee Camp in 2013. Azraq Refugee Camp, the second-largest camp, opened later in 2014 and is currently housing more than 39,000 refugees in 8,850 shelters.

While numerous national and international NGOs provided all services and aid support inside the camps, the movement of refugees to the nearby cities was severely constrained, leading the dwellers to refer to the camps as their homes. In the interim, Jordan established the Syrian Refugee Camps Directorate (SRCD), a governmental entity with official status, to organize the camp settlements and work in tandem with all other national and international organizations present in the camps.

Along the way, the organizations created programs known as “durable solutions” to support the refugees’ stay in the camp while also providing aid. Being a registered refugee and residing in one of the recognized refugee camps are prerequisites for receiving benefits from those programs.

According to the Memorandum of Understanding between UNHCR and the government of Jordan, drafted in 1998, UNHCR has been tasked with registering and issuing documents to refugees and asylum seekers subject to annual renewal using the “continuous registration” processes, which entail updating vital events (birth, death, divorce, and marriage) as well as specific needs and vulnerabilities. The latter tasks were completed in agreement and close coordination with the government, which additionally issues MOI service cards to Syrian refugees upon receipt of registration and supporting documentation from UNHCR. A legal stay, protection, and access to services like primary health care and education are guaranteed by UNHCR and the Ministry of the Interior, and these documents serve as the legal basis for assistance from NGOs and UN agencies. However, the UNHCR card is only available to Syrians who entered Jordanian territory illegally; Syrians who entered Jordan legally are not eligible to obtain or use the UNHCR card.

Providing activities that would save lives, like shelter, food, and medical care, was the camps’ main objective during their formative years. Registered refugees were provided with blankets, sleeping mats, and essential food packs before being distributed to tents. The United Nations World Food Programme (WFP) provided dry food rations and daily bread distributions during this time. Later, refugees got access to cash assistance, which allowed them to set up shops and businesses within the camp. The United Nations World Food Programme (WFP) in Jordan has distributed food vouchers to all Syrian refugees living in camps, allowing them to buy the food of their choice from designated shops inside the camp. In response to the change in the governance direction that is covered in the later section, both the cash assistance and food voucher programs were later expanded to assist refugees living outside of the camps in urban areas.

Encampment lessons unlearned

Although Jordan has established and managed many refugee camps before, some important lessons from those earlier experiences were not retained. The situation in the Zaatari refugee camp began to bring back memories of a challenging refugee situation of permanent temporariness that Jordan experienced with the influx of other refugees, a pattern that could be repeated.

Until 2013, Jordanian security forces were concentrated at the camp’s entrance and around the perimeter, rather than providing law and order within the camp. As a result, community structures formed naturally among the refugees, forming informal self-governance systems. Refugees with common places of origin in Syria clustered in groups and formed reciprocal support among themselves. Many defined their clustering territory and provided some form of group protection. Meanwhile, the absence of official law and order representation by the authorities created an atmosphere of impunity that allowed powerful individuals and organized gangs to form destructive groups (UNHCR, 2013). They posed a threat to the refugees’ peace and well-being by engaging in criminal activities, sexual exploitation, and diverting aid that arrived at the camp, a problem that was heavily addressed in the UNHCR report in 2013.

The dialogue between refugees and any official entity was also so limited. The contact between them was primarily at arrival for registration purposes. In some cases, refugees use demonstrations and violence to make their voices heard. A lack of community ownership of communal spaces and a lack of a sense of belonging among refugees have also been highlighted by the UNHCR in their periodic reports. This eventually led to the vandalism of spaces such as administration offices, communal kitchens, and WASH facilities (UNHCR, 2013).

Reasserting the encampment governance of the Syrian refugee crisis

A dynamic reassertion in the governance of the Syrian refugee situation was witnessed after a year of the emergency mood and nearly a year before moving forward and opening the next largest camp for Syrian refugees in Jordan. Almost halfway through 2013, the Zaatari governance plan was set to acknowledge the setbacks of the prior approach and to address the essential need for restructuring the camp, enhancing its security capacities, and improving community engagement. The new plan was also intended to end nearly 3,000 businesses (see Figure 3) and limit the informal economic activities that the refugees established by selling the humanitarian aid they receive, including the shelters. A challenge that was later viewed as an opportunity to stretch limits in order to embrace new donors by promoting Syrian refugees as entrepreneurs (Turner, 2019).

Figure 3: Zaatari Refugee Camp showing economic activities by the refugees. Source: Kamel Dorai

The camp was accordingly rearranged into 12 neighborhoods, and tents were gradually replaced by prefabricated housing units (caravans). (see Figure 4). The new plan was to follow the “governance dividends” approach by decentralizing camp administration and service delivery. The government appointed the Syrian Refugee Camp Directorate (SRCD) as the body responsible for camp security. Accordingly, the Jordanian authorities expanded their security forces’ presence and community police inside the camp, while legal mechanisms for integrating the camp’s perimeter into the Jordanian judicial system were established.

Figure 4: Zaatari Refugee Camp. Source: Kamel Dorai

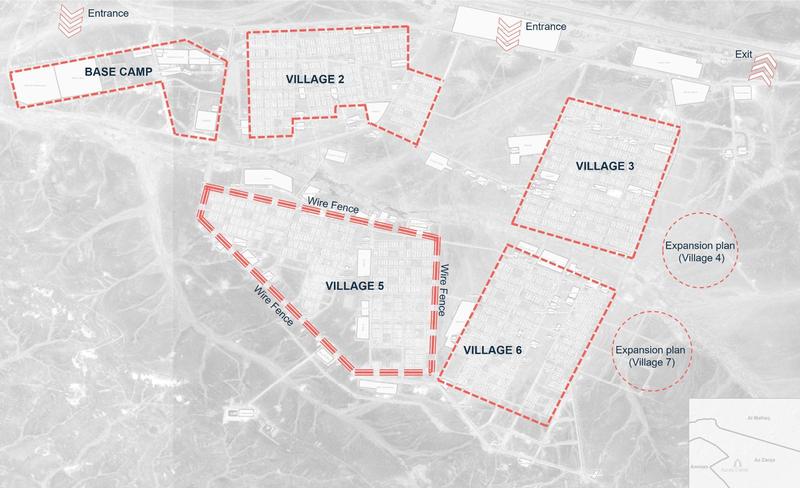

The Azraq camp, established in 2014, witnessed changes in governance and physical structures in comparison to the Zaatari (Dalal et al., 2018). Unlike usual, the Azraq camp took careful planning and a year-long of preparation. The UNHCR and the government’s designers, planners, and decision-makers view the Azraq camp as an innovation that set the bar high and took into account all of the challenges posed by the Zaatari. The new camp was intended to practice control mechanisms over its inhabitants through the design, planning, and management of the built environment. Azraq camp adopted the clustering urban planning method, which divided the camp into independent villages with a centralized distribution of services for each village, as opposed to the majority of earlier refugee camps in Jordan. Village 5 is used as a detention place (Gatter, 2023), where Syrian refugees coming from the camp of Rukban at the border are settled. The village is disconnected from other places, and mobility for the Syrians is prohibited (see Figure 5). This time, unmovable shelters were used, making it easier for authorities to assign fixed addresses to camp residents. Long car rides between villages made it almost impossible for residents of each village to interact with one another. Separating the villages was a deliberate design choice to restrict political mobility among refugees. The location of the administrative base camp was accordingly chosen to allow easy and quick access to all other villages, ensuring that the police and humanitarian organizations are fully in charge (Dalal et al., 2018). The UNHCR’s role in managing the Azraq camp was also reduced as the full SRAD and police took control of the camp. In comparison to Zaatari, the involvement of NGOs and humanitarian relief was also marginalized.

Figure 5: The site plan of the Azraq refugee camp in Jordan showing the villages. Source: Zaid Awamleh based on Google Earth in 2018

Governance toward urban settlements

Decisions and policies that promoted urban settlements:

Figures will be used to present this section.

- Promoting and supporting refugee employment programs in local businesses.

- Shifting strategies toward development programs rather than emergency responses.

- Replacing the Syrian Refugee Camps Directorate (SRCD) with the Syrian Refugee Affairs Directorate (SRAD).

- Legislate new laws that allow Syrian investors to obtain Jordanian citizenship.

- Providing support and aid services for the refugees settled in urban cities.

From emergency responses to development programs

Approaching the end of 2013, 449,192 Syrian refugees were registered in Jordan outside the UNHCR camps. 60% of Syrian refugees have settled in the three northern cities collectively, which are close to Syria’s borders, compared to 30% who have settled in Amman. In some neighborhoods, Syrian refugees constituted the majority in comparison with the host communities in the northern cities (Bank, 2016). Refugees were mainly living in rented apartments, half of which were perceived as substandard, according to the UNHCR home visits project.

In some of the northern Jordanian cities, such as Mafraq, property owners and local entrepreneurs profited from the presence of refugees and the influx of international aid money. While this benefited some communities, it also created socioeconomic pressures on others by increasing housing markets and employment competition, as well as decreasing access to and quality of public services, which paved the way for social tensions to emerge between refugees and host communities.

Under the joint leadership of UNHCR and UNDP, the international community implemented a new comprehensive approach to the Syria crisis that combined humanitarian and development responses into a single cohesive plan in line with national plans and priorities. The UN gathered international efforts at the end of 2014 to present the 3RP, which condensed one region plan covering Turkey, Lebanon, Jordan, Iraq, and Egypt. The 3RP is a strategic, coordination, planning, advocacy, fundraising, and programming platform for humanitarian and development partners to respond to the Syrian crisis (3RP, n.d.).

Jordan responded by enacting a number of policy measures in line with the new approach. The government announced the National Resilience Plan (NRP) and the Host Community Support Platform (HCSP) to provide a strategic framework for refugee crisis governance and to support the Jordanian host communities in the most affected areas of the Kingdom. Later, they launched the Dead Sea Resilience Agenda, held the resilience development forum, and established the Jordan Response Platform for the Syria Crisis (JRPSC).

Refugee urban settlements facilitated by jobs, investments, and citizenships

While Jordan brought together the public and private sectors to enhance the business environment for Syrian refugees, the ILO promoted jobs for communities that are hosting refugees. The 2016 Jordan Compact was described as a game-changer for conventional referee governance (Huang & Gough, 2019). Based on an agreement between the World Bank, the European Union, and the Jordanian government, the Compact integrated Syrian refugees into the Jordanian garment export factories (Kridis, 2021). Successively, the Jordanian Ministry of Labour issued more than 100,000 free-of-charge work permits for Syrian refugees by June 2016. Later in 2017, Jordanian trade unions began issuing work permits in the agricultural and construction sectors.

Following the Jordan Compact in 2016, the Jordanian government has developed a policy to promote the employment of Syrians in Jordan’s Special Economic Zones (Lenner & Turner, 2018). “While innovative, the Compact will not upset the status quo by creating Syrian competition with Trans-Jordanians for employment” (Ali, 2021). In 2018, unemployment rates among refugees have fallen from about 60 percent to about 8 percent (Stave et al., 2021). The work permits that are delivered concern segments of the labor market where Jordanians are not represented and are already taken by migrant workers. At the beginning of the implementation of the program, Jordan announced a three-month suspension of legal proceedings against refugees working without a permit in order to give their employers time to regularize their situation, while later the permits were exempt from fees and obtained online. On a total of 200,000 expected work permits, more than 230,000 permits have been issued to Syrian refugees by 2021 (Stave et al., 2021). The labor market has only been opened in limited economic sectors. Jordanian legislation generally only authorizes the employment of foreigners on the condition that it compensates for a lack of qualifications or human resources within the Jordanian labor force in certain sectors and according to pre-established quotas, mostly in the agriculture and construction sectors (Husseini, 2022).

These collective efforts laid the groundwork for Syrian refugees to move from camps to urban settings, primarily in Jordan’s industrial and agricultural cities. Refugees living in camps can apply for leave permits to work in communities or for other reasons (including more complicated health interventions, weddings, family and humanitarian reasons, etc.). Those stays can be for several days or even two weeks, with the possibility of permit renewal. They may also request to permanently leave the camp, which the authorities will consider on a case-by-case basis. Refugees who have work permits may rely on them to leave the camps they reside in for a full month without seeking permission from the camp administration.

This easing of movement was further consolidated by the decision of the Jordanian Ministry of Interior to replace the Syrian Refugee Camps Directorate (SRCD) with the Syrian Refugee Affairs Directorate (SRAD), which expanded its purview to include all Syrian refugees living in the Kingdom and did not restrict its role to camps only. In 2021, the SRAD facilitated the acknowledgment of the service cards that the Ministry of Interior started issuing back in 2014 for refugees registered with the UNHCR as an official ID that facilitated access to public services like free education and subsidized healthcare outside of the camps.

The opportunities for more business owners and their employees to relocate to Amman, the capital of Jordan, where the majority of decisions, services, and governmental buildings take place, were also promoted by the new policies. Some Syrian business owners saw the new policies as an opportunity to relocate their operations from Syria to Jordan and establish themselves, along with their employees and business partners, in urban areas.

According to Investment Law No. 30 for 2014, Syrians can obtain Jordanian citizenship if they become investors. It’s also allowed for Syrians to apply with a request to issue residency in Jordan if they are investors, whether in category A or category B. Syrians who possess an investor card are permitted to leave and enter the Kingdom of Jordan, and they are also permitted to own properties, whether houses, companies, commercial shops, lands, or cars. Syrian workers are also subject to Jordanian labor law, so they can subscribe to social security institutions and withdraw their accruals of social security at the end of their work or whenever they want, unlike Jordanian workers, who can only withdraw their accruals after the end of their work.

“Due to previous lows, Jordan was off the map for business.” “As a manager of a company, you always need to make visits to the countries you work with in order to establish business relations with them,” a Syrian business owner said in an interview. He added, “This issue has been resolved by the Jordan Investment Commission (JIC), as the foreign investors were finally granted Jordanian citizenship and were able to travel back and forth, which motivated me to move my business to Jordan.”

Concluding remarks and reflections

This CMI Report discussed how the shifts in the governance strategies and agendas of the Syrian refugee crisis in Jordan have shaped the refugee settlements between the camps and the urban cities. The work used critical analysis to examine the spatial governance of the crisis and its impact on settlement characteristics, which were reflected in both major and minor policies and decisions by Jordan, as a host country, the international community, and humanitarian organizations.

By switching from the traditional means of providing emergency aid and shelters to inclusive programs that are thought to be beneficial to both host communities and refugees, a clear shift in the hosting strategy for Syrian refugees is seen. One of the preeminent remarks in this shift was the openness to include Syrian refugees in the jobs market, as seen in the provision of work permits, ease of movement, ownership allowances, and citizenship opportunities, all of which had an impact on where and how refugees could settle.

Refugees in camps with work permits are now able to legally relocate to industrial, agricultural, and urban cities. Due to the UN’s expansion of services outside of the camps and the government’s recognition of the service cards as an official ID, refugees are now still eligible to receive aid and have access to public services even after leaving the camp. The opportunities for residency and citizenship allowed Syrians to start their own businesses and hire other Syrian refugees, which encouraged a sizable number of refugees to settle in Amman, the capital of Jordan.

Jordan announced a new Investment Environment Law number 21 in April 2023, given the fact that the unemployment rate among 15- to 24-year-olds reached 47.2% and the country had come to realize the negative effects of the open-ended investment and work permit policies on the Jordanian host communities. The decision, which may have an impact on the situation of refugees in the near future, forbade non-Jordanians from working in a number of occupations, including those requiring administrative, industrial, and handcrafts labor (Mustafa, 2023).

Although this report argued that when it comes to the encampment in Jordan, lessons should have been learned from the numerous prior experiences, policymakers can also argue that camps are kept to attract humanitarian aid (Tsourapas, 2019), particularly when it comes to a nation with limited resources and a challenging economic situation. Refugee camps are used as a setting for stories about vulnerabilities where donors can discover their interest in taking part in a humanitarian response to a refugee crisis. These stories often involve difficult living conditions, chaos, and trauma. In fact, one can argue that Jordan has learned a lot from the Iraqi refugees’ non-encampment in the 2000s, when attempts at an impulsive response by the international community and donors were severely constrained.

Not long after the UN and the government expressed disturbance over the refugees’ informal economic activities in Zaatari, a new narrative was developed in an effort to entice new donors. Encamped Syrian refugees, particularly those who have settled in the Zaatari refugee camp, have been promoted as entrepreneurs (Turner, 2019) in an effort to change the long-held perception of refugees as passive and dependent on humanitarian aid. These efforts came to support the new humanitarian perspective of responsibilizing refugees within the context of “resiliency humanitarianism” undertaken by the UN (Ilcan & Rygiel, 2015). An agenda that was completely abandoned in the next largest camp for Syrians in Jordan; the Azraq refugee camp.

Humanitarian planners in Za’tari believe the camp to be a failure in terms of planning refugee spaces (Gatter, 2018), whereas the discourse surrounding Azraq was completely the opposite, portraying it as an ideal camp that resolved all problems that appeared in Zaatari. Meanwhile, many researchers and activists see it as an absolute use of architectural design and urban planning to practice control and power over refugees. While Azraq refugee camp eventually succeeded in delivering the objectives it was designed for, it is seen as an exemplary situation for violence contained by humanitarian logic (Hoffmann, 2017). The domestic political conflict in Syria has indeed displaced refugees with different political agendas and backgrounds, yet it is apparent that the vast majority of the Syrian refugees in Jordan are war refugees and not refugee warriors (Bank, 2016), a fact that might have been overlooked when designing the new “ideal” camp. The majority of the Azraq camp was eventually left empty (Davis, 2022) due to a shift toward urban settlement programs and a decrease in the number of refugees influxing to Jordan as a result of new security measures and border closures.

There is a constant debate about whether to humanize or politicize refugee situations. It appears to be much more complex than academics, theorists, politicians, and humanitarian workers can express in a framework that can be discussed exclusively within one. On the ground, it would appear that politicizing the refugee situation is a necessity that should come back and forth in the refugees journey in order to attempt humanizing it.

The Amman-held consultative meeting of the foreign ministers of Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Egypt, and Syria, hosted by Jordan in April 2023, might have laid the foundation for a new change in how the Syrian refugee crisis is being managed. The meeting prioritized safe voluntary repatriation for the Syrian refugees and seeded the Arab League’s decision to re-admit Syria effective May 7th, 2023, 12 years after suspending its membership (JT, 2023). All of which might lead to new political scenarios and governing structures to accommodate the most recent regional diplomacy toward Syria.

References

(n.d.). Syrian Legal Platform. Retrieved May 10, 2023, from https://legal-sy.org/

Ali, A. (2021). Disaggregating Jordan’s Syrian refugee response: The ‘Many Hands’ of the Jordanian state. Mediterranean Politics, Volume 28(Issue 2), 178-201.

Bank, A. (2016). Syrian Refugees in Jordan:: Between Protection and Marginalisation. German Institute of Global and Area Studies (GIGA).

Dalal, A., Darweesh, A., Misselwitz, P., & Steigemann, A. (2018). Planning the Ideal Refugee Camp? A Critical Interrogation of Recent Planning Innovations in Jordan and Germany. Urban Planning, 3(4).

Davis, H. (2022, March 29). A life of isolation for Syrian refugees in Jordan’s Azraq camp. Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/3/29/a-life-of-isolation-for-syrian-refugees-in-jordans-azraq-camp

Gatter, M. (2023). Preserving order: narrating resilience as threat in Jordan’s Azraq refugee camp. Territory, Politics, Governance, 11, 695-711.

Gatter, M. (2023). Time and Power in Azraq Refugee Camp: A Nine-to-five Emergency. American University in Cairo Press.

Gatter, M. N. (2018, February 20). Rethinking the lessons from Za’atari refugee camp. Forced Migration Review. https://www.fmreview.org/syria2018/gatter

Hoffmann, S. (2017). Humanitarian security in Jordan’s Azraq Camp. Security Dialogue, 97–112.

Huang, C., & Gough, K. (2019, March 12). The Jordan Compact: Three Years on, Where Do We Stand? - Jordan. ReliefWeb. https://reliefweb.int/report/jordan/jordan-compact-three-years-where-do-we-stand

Husseini, J. A. (2022). Vulnérabilité et intégration en Jordanie : les réfugiés syriens dans leur environnement local. AFD. https://www.afd.fr/fr/rt_67_vulnerabilite_integration_jordanie_refugies_syriens_al_husseini_padieu

Ilcan, S., & Rygiel, K. (2015). “Resiliency Humanitarianism”: Responsibilizing Refugees through Humanitarian Emergency Governance in the Camp. International Political Sociology, Volume 9(Issue 4).

JT. (2023, May 7). FM attends Arab League meeting as Syria’s participation restored. Jordan Times. https://jordantimes.com/news/local/fm-attends-arab-league-meeting-syrias-participation-restored

Kridis, B. B. (2021, May 17). The Jordan Compact: A model for burden-sharing in the refugee crisis. Refugee Law Initiative Blog. https://rli.blogs.sas.ac.uk/2021/05/17/the-jordan-compact-a-model-for-burden-sharing-in-the-refugee-crisis/

Lenner, K., & Turner, L. (2018). Making Refugees Work? The Politics of Integrating Syrian Refugees into the Labor Market in Jordan. Middle East Critique, 65-95.

Mustafa, M. I. (2023, April 9). Guidelines banning foreign workers from certain professions ignite controversy. Jordan Times. https://jordantimes.com/news/local/guidelines-banning-foreign-workers-certain-professions-ignite-controversy

Stave, S. E., Kebede, T. A., & Kattaa, M. (2021, September 2). Impact of work permits on decent work for Syrians in Jordan. ILO. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---arabstates/---ro-beirut/documents/publication/wcms_820822.pdf

3RP. (n.d.). 3RP. 3RP Syria Crisis – In Response to the Syria Crisis. https://www.3rpsyriacrisis.org/

Tsourapas, G. (2019). The Syrian Refugee Crisis and Foreign Policy Decision-Making in Jordan, Lebanon, and Turkey. Journal of Global Security Studies, 4, 464-481.

Turner, L. (2019, October 25). ‘#Refugees can be entrepreneurs too!’ Humanitarianism, race, and the marketing of Syrian refugees. Review of International Studies.

UNHCR. (2013). Zaatari Governance Plan. UNHCR.