Partisan Circle Dances (part 1)

Hey Kozara, hey Kozara, my thick woodland

You are hiding, you are hiding many a partisan.

How many, hey, how many are there on Kozara tree branches

There are even more, hey, even more young partisans.

How much, hey, how much is there on Kozara leaves

There are even more, hey, there are even more young communists.

These are some of the most famous verses sung by the Yugoslav partisan soldiers and their supporters during World War II. Their foundation is a short rhyming couplet appropriated from the popular folklore form known as bećarac. Every rhyming couplet is one unit, one independent poem. If the couplets had a similar theme, singers would sometimes put them together in order to create a new, longer poem, and sometimes singers omitted the couplets that, for instance, they could not remember.

The couplets acted as poetic comments on all life experiences, in both peace and war. The brevity of the couplets and familiarity of their form made it possible for everyone to understand the gist and participate in their further dissemination.

Partisan commentators thus established that:

Our struggle demands

That one sings when one dies.

Women partisans often sung:

Who could've known last year, comrades,

That girls would become partisans.

or

I’m your only daughter, oh, mother of mine

I am leaving you to carry a carabine.

Of course, daily news – such as the standoff of the Nazi army before Stalingrad or the capitulation of Italy – were regularly commented on:

Hey Hitler, what the hell,

Why does your army stall?

Either you can’t, or winter has met you,

Or the Russian offensive beats you.

and

Rejoice, brothers partisans

Italians by themselves gave up their guns.

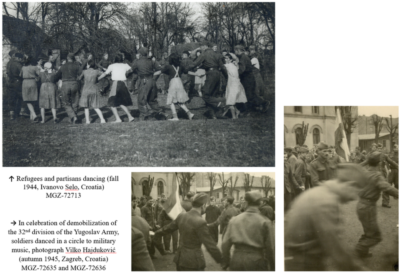

Partisans sang these kinds of songs in their free time, on the march, and in the military hospitals, either in the darkness of their hospital rooms lying on their improvised, often straw beds, or in groups while enjoying fresh air – maybe even some sun – in front of the hospitals. However, they were most often sung while soldiers as well as civilians held hands and moved to the rhythm of singing.

The movement was, of course, a circle dance, probably the oldest dance formation common to many cultures. It was most often performed in a semicircle or a curved line to musical accompaniment while the person at the head sang the verses that the rest of the group then repeated. One participant of the war told the Slavist and folklorist Maja Bošković-Stulli that “When I was in a circle, I would invent and sing, I would sing both my own and other people’s [verses]. I was a part of the people. We were all one then, we fought and sang.”

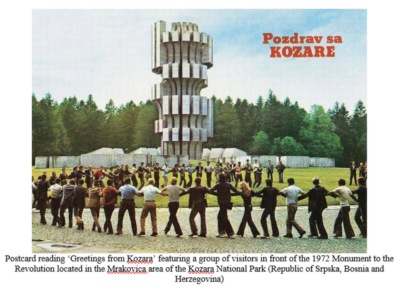

The couplet and the circle dance – particularly the variation that became known as the circle dance of the Kozara mountain – became a means of communication during the war that strengthened the fighting community and encouraged their togetherness and perseverance. Their symbolic role has also become part of the cultural memory of the war.

Translation of the couplets: my own.

Photographs 1–3: Muzej grada Zagreba (Zagreb City Museum), Collection Militaria

Photograph 4: Spomenik database, https://www.spomenikdatabase.org/kozara

Bibliography

Bošković-Stulli, Maja. Petokraka, zašto si crvena: narodne pjesme iz ustanka (Five-pointed Star, Why Are You Red: Folk Poems of the Uprising). Zagreb: Lykos, 1959.

Bošković-Stulli, Maja. “Narodna poezija naše oslobodilačke borbe kao problem savremenog folklornog stvaralaštva” (“Folk Poetry of Our Liberation Struggle as a Matter of Contemporary Folklore Creation”). Belgrade: Etnografski institut Srpske akademije nauka, 1960.

Rihtman-Auguštin, Dunja. “Folklor kao komunikacija u NOB” (“Folklore as Communication during the NOB”). In Kultura i umjetnost u NOB-u i socijalističkoj revoluciji u Hrvatskoj (Culture and Art in the NOB and Socialist Revolution in Croatia), edited by Ivan Jelić, Dunja Rihtman-Auguštin, Vice Zaninović, 151–166. Zagreb: Institut za historiju radničkog pokreta Hrvatske, 1975.