antonio.delauri@cmi.no

War and Fun: Reconceptualizing Warfare and Its Experience (WARFUN) is a research project funded by the European Research Council and led by Research Professor Antonio De Lauri.

Fun has every shade of connotation, from the most joyful to the most sinister. In the framework of this project, fun represents an entry point into a deeper realm of war and soldiering. An understanding of the complexity of participation in war requires an epistemic change in conventional learning and debate. The overall objective of this project is to offer a new understanding of war and soldiering through a study of the role and implications of fun for soldiers and veterans.

The suffering and hardships that humans endure within war cannot be stressed enough. It is precisely for this reason that we urgently need a more nuanced understanding of what it means to be at war. WARFUN investigates the plurality of experiences and affective grammars that are generally neglected by normative approaches. Anthropological studies have emphasized the ambivalent sentiments that arise as troubles escalate during large-scale violence and the crucial role that social actors have in determining the magnitude and consequences of conflict. War can only be understood through the broadest and the most complex assemblages of emotions and imagination available. It is only by taking the wide array of sensations and emotions into account that we will be equipped to understand how war blurs the boundaries between the extraordinary and the ordinary and to foresee the long-term, articulated effects of war on those who practice it. This consideration builds on the assumption that war has a co-participative epistemic nature, since it cannot be simply described as the by-product of political decisions from above; it is also determined by participation and initiatives from below.

Building on multisited research and mixed-methods approach, the project will explore the role of fun in the symbolic and concrete reproduction of practices and narratives involved in the construction of the enemy; it will study the mechanisms of normalization of war and the articulation of different emotions among soldiers and veterans; it will address the relationship between agency, complicity, and participation in situations of social disruption and violence; and it will contribute to debates about hazing and sexual violence in the military.

WARFUN is a European Research Council (ERC) Consolidator Grant project - Grant agreement ID: 101001106.

People

Advisory Board

Publications

Oppressive Language and Humanitarian Complicity: Reflections on Gaza and European Border Violence

Unacceptable War Pleasures: The Harsh Treatment of Norwegian “German Whores” (Tyskertøser) post-WW2

Playing war: Norwegian soldiers’ experiences of fun and responsibility in Afghanistan

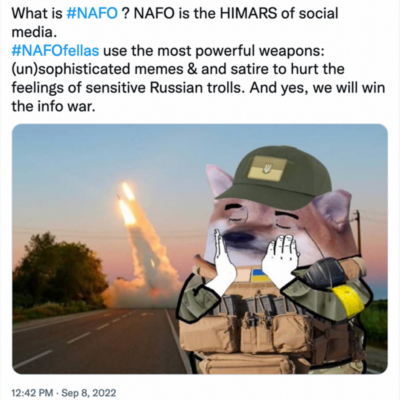

‘Unleash the hounds!’: NAFO’s memetic war narrative on the Russo-Ukrainian conflict

‘Fornøyde veteraner? Hvordan skal vi forstå norske Afghanistan-veteraners positive opplevelser av vekst og mestring?'

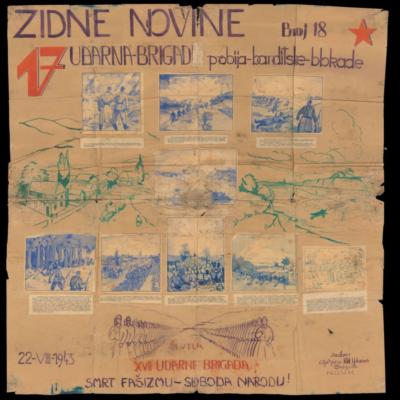

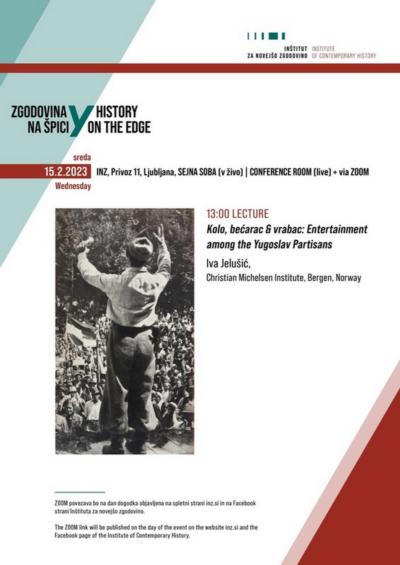

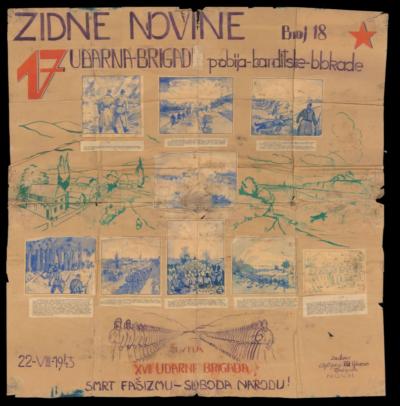

Exploring War&Fun: Insights from the Yugoslav People’s Liberation Struggle (1941-1945)

The Self-Realising Soldier: Post-Heroic Reflections from Norwegian Afghanistan Veterans

Women, Fun, and Women’s Way of Having Fun during the People’s Liberation Struggle

'Unleash the hounds!': NAFO's memetic war narrative in the Russo-Ukrainian conflict

Better than sex? Norwegian Soldiers’ Experiences of Thrill and Pleasure in Afghanistan

Neretva and Sutjeska in Horror and Magic of Individual Remembrances

Podcast: Adventure, precarity and colonial nostalgia: A conversation with Jethro Norman’

"ARE YOU HEADING TO THE FUN ZONE?": NOTES FROM THE POLISH-UKRAINIAN BORDER

The seduction of war: Norwegian soldiers` quest for adventure, thrill, and self-realisation.

Podcast

Welcome to the WARFUN Podcast. The WARFUN podcast investigates the plurality of experiences, the emotional implications, and the narratives of war from the perspective of those who fight. Through these conversations, the WARFUN podcast aims to offer a more nuanced understanding of what it means to be at war and how war blurs the boundaries between the extraordinary and the ordinary.

Episode 01: Is there a place for fun and pleasure in war research? A conversation with Catherine Lutz

In this episode, Eva Johais and Catherine Lutz discuss whether we can and should study fun in the context of war. This means dealing with moral and conceptual questions of conducting research on war. Why does Catherine Lutz call for “decentering the battlefield”? How can our own moralities inhibit our understanding of war as a central phenomenon in the contemporary world? And what forms of pleasure do people feel when they go to war?

Episode 02: Consumerism in the service of pleasure and fun during the Vietnam War. A conversation with Meredith Lair

In this episode, Iva Jelušić and Meredith Lair talk about the life of the US soldiers in army bases during the Vietnam War. The conversation first focuses on some of the findings from Lair’s book Armed with Abundance: Consumerism and Soldiering in the Vietnam War (2011), which examines the non-combat experiences of American soldiers in Vietnam. The second part of the conversation brings to the fore her current research, including soldier photography during the same war.

Episode 03: Adventure, precarity and colonial nostalgia: A conversation with Jethro Norman

In this episode, Heidi Mogstad talks to Jethro Norman about his ethnographic research with European veterans working and living as private military and security contractors in East Africa. Jethro argues for the importance of taking seriously the voices and experiences of veterans and ‘mercenaries’, including their attachments to and critiques of their own societies, the military, and national and colonial history.

Episode 04: Croatian veterans’ serious war games. A conversation with Sven Milekić

In this episode, Iva Jelušić and Sven Milekić talk about the activities of Croatian veterans of the 1990s conflict active in veterans’ associations. The conversation focuses on the veterans' strategies of self-presentation to the public and instances where the observer can glimpse pleasure despite their emphasis on severity and sacrifice.

Episode 05: Theatre in the context of the Yugoslav Wars. A conversation with Jana Dolečki

In this episode, Iva Jelušić and Jana Dolečki discuss theatre in the context of the disintegration of socialist Yugoslavia and the Yugoslav Wars. The conversation focuses on the theatrical performances of the so-called frontline theaters and in the theaters outside war zones (in Zagreb and Belgrade). In the second part of the conversation, they consider some more general claims about theatre and its merits in the times of war.

Episode 06: War as a game: The playful aspects of the Daring Ones’ military and paramilitary experiences, 1917-1922

In this episode, Blasco Sciarrino presents the Italian elite army corps known as the Daring Ones (Arditi), which fought mainly in the First World War. He discusses how having fun increased their fighting power in the course of war and their subsequent paramilitary activism, and considers if the playfulness and collective pursuits increased not just the Daring Ones’ military prowess, but also several of these men’s resolve to use violence. The illustrations that are mentioned in this episode can be found in the WarFun visual archive.

Episode 07: Musical entertainment in the British Armed Forces during the Great War (1914-1918). A conversation with Emma Hanna

In this episode, Iva Jelušić and Emma Hanna talk about wartime entertainment and recreation in the British Armed Forces during the First World War. The focus of the conversation is on the relevance of musical activities to rank-and-file soldiers and their impact on soldiers’ morale and well-being. Read more about the cover image for Emma's book, Sounds of War, and why she chose it in the WarFun visual archive.

Episode 08: Fun and the soldier trophy selfies. A conversation with Elissa Mailänder

In this episode, Iva Jelušić and Elissa Mailänder talk about her research of soldier amateur photography, particularly during the Second World War. The focus of their conversation is what can be discovered about the soldiers and the ways they had fun through these seemingly banal tokens of war.

Episode 09: Living for a better future at the El Shatt refugee camp. A conversation with Florian Bieber

In this episode, Iva Jelušić and Florian Bieber talk about the El Shatt refugee camp in Egypt that operated during the final two years of World War II. The conversation provides an overview of the functioning of this camp, the life of the people in it, and the aspects that made it a well-organised as well as a joyful establishment, which was different from other refugee camps.

Episode 10: On Many Roles of Music during the Siege of Sarajevo (1992-1995). A Conversation with Petra Hamer

In this episode, Iva Jelušić and Petra Hamer talk about musicking in the besieged Sarajevo. The conversation covers many related aspects, from practical issues arising from the lack of electricity to the activities of musicians who stayed and those who fled as well as music-related activities of the soldiers. Petra talks about the omnipresence of music in the city and the reasons why it was completely expected.

Episode 11: Frames and experience of soldiering in Germany. A conversation with Maren Tomforde

This episode first traces how public perceptions of soldiers have changed over time, including the recent reappraisal of the status of the armed forces in the face of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The episode also sheds light on how soldiers experience civil-military relations. Against this background, the conversation revolves around German society’s relation to war. The conversation then digs into ostensibly contrasting realms of soldier experience. It addresses mechanisms to deal with fighting and killing and reveals the unexpected omnipresence of humor in soldier life.

Episode 12: The ‘bad’ anthropologist? A conversation with Thomas Randrup Pedersen about military anthropology and soldiering in the post-9/11 era.

In this episode, Heidi Mogstad and Thomas Randrup Pedersen discuss anthropological attitudes to research on the military and some of the ethical and methodological complexities of studying and writing about soldiers and warfare. Pedersen shares experiences from his fieldwork with combat troops in Afghanistan and Iraq and reflects on his turn to existential anthropology. Mogstad and Pedersen also discuss some of their overlapping findings, including soldierly tropes of adventure, fun and post-war growth.

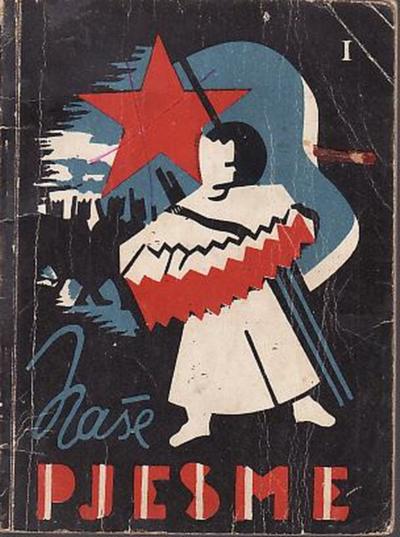

Episode 13: Partisan Struggles of the Past, Present, Future

In this episode, Iva Jelušić and Gal Kirn talk about the Yugoslav People’s Liberation Struggle. Discussing the Partisan art created during the war, especially on the territory of Slovenia, they consider how wartime art production supported the resistance to fascism and complemented it as well as what its values are relevant today and how it could remain relevant in the future.

Episode 14: Humour, War and International Relations

In this episode, Eva Johais discusses with Christopher Browning and James Brassett what a focus on humour reveals about international politics. With (international) politics increasingly becoming a site of ‘comedification’, they make compelling arguments why humour should be taken seriously. Be it its function as a mechanism of anxiety management, a tool of both governance and resistance, or its role in constituting political community, a focus on humour sheds light on both high politics and the politics of the everyday. Considering the differential role of humour in the Russia-Ukraine war and the conflict over Gaza they point out the constitutive role of humour in each case. Why, for whom and with what consequences has one of these conflicts been more ‘fun’ than the other?

Episode 15: The Presence–Absence of Violence: A Conversation with Eva van Roekel on the Importance and Challenges of Perpetrator Research

In this episode, Heidi Mogstad speaks with cultural anthropologist Eva van Roekel about her unconventional research on war perpetrators in Argentina—individuals indicted for crimes against humanity during the so-called Dirty War (1974–1983).

The two anthropologists discuss the ethical and methodological challenges of studying soldiers who have committed acts of violence and atrocity, and how engaging with their perspectives can complicate, but also enrich, prevailing theories as well as our moral and political assumptions.

Visual archive

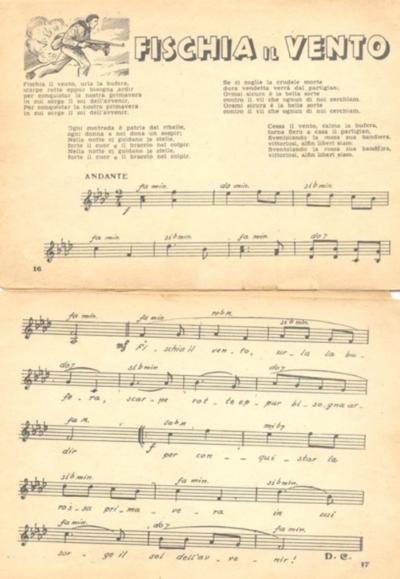

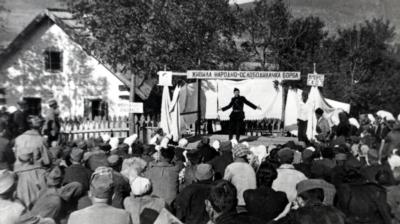

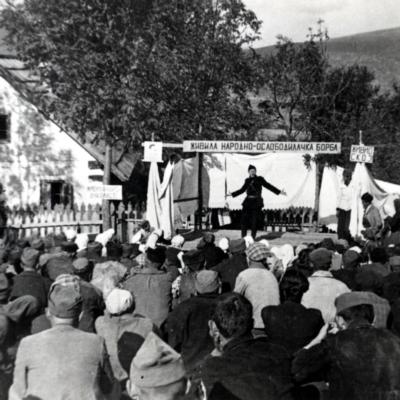

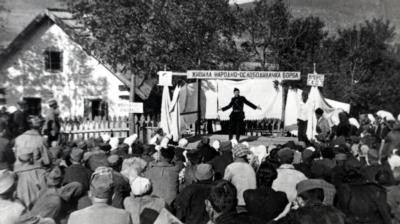

Partisan Anthems

During the Yugoslav People’s Liberation Struggle, anthems proliferated. Throughout the Yugoslav territories, The Internationale (Soviet state anthem until 1944) was widely popular. The song Hej, Slaveni (Hey, Slavs), which would become the official anthem of socialist Yugoslavia, as well as the anthems of the future republics were sung with joy. In addition, anthems to the Partisan struggle and its values, to the military units, and to significant personalities were composed during the course of the war and sung at rallies and political performances as well as in small, more private gatherings.

It is worth emphasizing Janez Kardelj’s Himna agitteatru (Anthem to the AgitProp Theatre). This one seems to be endeavoring to answer some of the key questions about the Partisan art and its role in the ongoing revolutionary transformation. The verses are as follows:

We are all here Partisan–actors,

Our home is nowhere, our stage everywhere.

We are comrades by our fighters’ side,

Now we are here, sorrow somewhere else.

Our words will not enlighten full-fed

Conceited masters in the theatre boxes,

Not in footlights but in deep forest,

They touch the heart of a fighter hero.

Green forest is now our auditorium,

The floodlight – the moon shining from the sky

Nothing is more valid than Partisans’ thanks

More than all the applause of the bourgeois world.

When the evening forest cloaks in darkness

And through it a secretive whisper runs,

Then through the night between the rocks

Echoes the free flight of our words!

And even if the distant voice disappears

Like shooting stars from the night sky,

Even then thousands sing within us

We are like the beat of one big heart.

You can hear more about the Partisan anthems and about the Partisan art in general on the WAFRUN podcast here.

Translation: Gal Kirn

Further reading:

Gal Kirn, The Partisan Counter-Archive: Retracing the Ruptures of Art and Memory in the Yugoslav People’s Liberation Struggle (Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter, 2020).

The Unexpected Sounds of War

Memoir literature about the Yugoslav People’s Liberation Struggle (1941-1945) is full of references to music. It was played and sung, Rodoljub Čolaković wrote, “somewhere on a march, at a [theatrical] performance, after a battle, in a tight spot when it was difficult, […] in spite of everything.”

Revolutionaries, especially volunteers in the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939) and communists who served in prisons throughout the Kingdom of Yugoslavia in the interwar period liked to sing revolutionary songs such as Bilećanka, the Italian Bella Ciao or the adapted Russian song Po šumama i gorama. The interwar city dwellers still enjoyed Vlaho Paljetak’s chansons and Ivo Tijardović’s operettas. The most numerous in the Partisan army and the resistance movement in general was the Yugoslav peasantry, which used folkloric expression in song and dance, particularly simple rhyming couplets and circle dances (as detailed in the cycle about the Partisan cicrcle dancing in this visual archive).

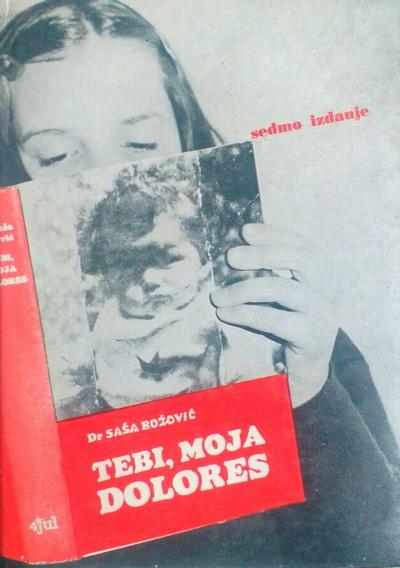

Some of the songs that the Partisans listened to and enjoyed listening to did not belong to any dominant tradition and they surprised with their presence. Partisan doctor Saša Božović wrote about one such composition. Namely, in one of the hospitals she managed, veterinarian Oto worked. According to her, one of his most important activities in that hospital was based on his knowledge of playing the violin:

“Oh my god, when he started to play! The bow glides as if on silk, and the arias spill out and fill the forest with something great and noble.

(…)

Since then, [the first time he played for the hospital staff and patients] Oto’s veterinary duties have been secondary. As soon as we stop and take a break, there is Oto and the violin. I can’t forget the wonderful nights, when the wounded, taken care of after dinner, lie down in the wonderful fragrant fir forest, and Oto circles around them, walks and plays. Already half of the wounded were asleep when Oto began Toselli’s Serenata. After several evenings like this, comrades from Bosnian mountains, Montenegrin stone, remote Serbian villages ask Oto for Toselli’s Serenata. Many are not pronouncing it well, but they feel it well.”

Author of the illustration: Dario Jelušić

Enrico Toselli’s Serenata: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wIY_bSn8-Jw

Sources:

Božović, Saša. Tebi, moja Dolores [To You, My Dolores]. Belgrade: Četvrti jul, 1984 (1979).

Čolaković, Rodoljub. Zapisi iz oslobodilačkog rata [Records from the Liberation War]. Zagreb: Matica hrvatska, 1947.

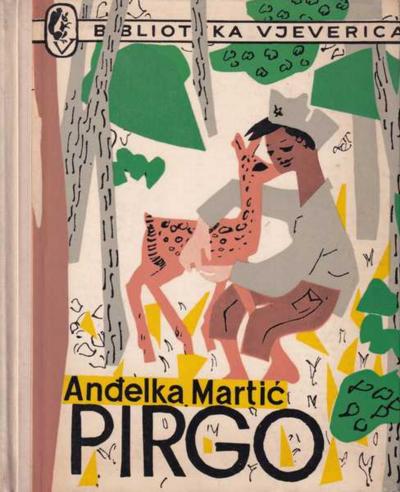

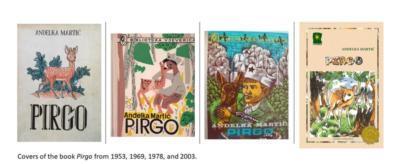

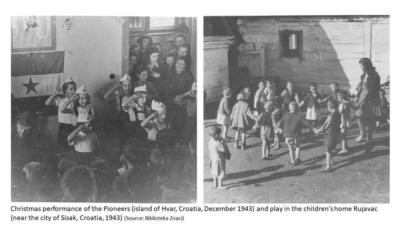

Pirgo

During an enemy bombardment, five-year-old Željko, “the smallest Partisan in the Slavonian forests,” hid in the woods. There he stumbled across a fawn that, it seems, had just become an orphan due to an enemy bomb. The boy and the fawn, whom Željko named Pirgo because of its freckles, were almost inseparable during the next year, and all the fighters of the Sixth Corps of Slavonia knew about them.

“You were a kiddie in a Partisan uniform. I met you in the spring of 1943 on the road to Voćin, where the Sixth Corps commissariat was passing,” Anđelka Martić, a former fighter of the XVIII Brigade of Slavonia, recounted to the already grown-up Željko. “I heard stories about your fawn,” she continued, “and already then I promised myself that I would write a novel for children about the two of you.”

The story of Željko and Pirgo is, of course, a story about fear before the dangers of war. Even more, it is a story about the mutual recognition of two powerless solitudes. The boy and the fawn were brought together in a world they did not actually belong to, and they created a tiny community based on friendship and tenderness.

The fact that the Partisan community in which the two lived during that one year showed not only understanding, but also content and even amusement with the situation – the soldiers checked in on Željko and Pirgo, sometimes teased them, and the duo even visited the nearby Partisan hospital in order to entertain and cheer up the wounded and sick who were recovering there – witnesses that even adults enjoyed the small everyday pleasures of this completely unusual friendship.

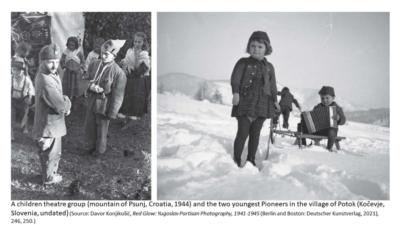

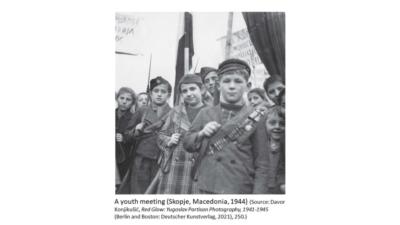

Importantly, in the Yugoslav People’s Liberation Movement, there were many families with children; Željko’s parents were active members of the Partisan army. In addition, wartime institutions tried to take care of war orphans throughout the country. Many children, when it was possible, were placed in Partisan children’s homes, and some, just like Željko, became a part of Partisan structures. Some children helped in Partisan hospitals, boys often helped in military units, mostly in auxiliary roles, and sometimes as couriers and even fighters. Some preserved photographs bear witness to the lives of children among the Partisans.

Sources:

Anđelka Martić, Pirgo (Zagreb: Mladost, 1953).

Veronika Mesić, “Anđelka Martić i herojska priča o Pirgu” [“Anđelka Martić and the Heroic Story about Pirgo”], interview by Veronika Mesić, Vox Feminae, May 1, 2019, https://voxfeminae.net/strasne-zene/andelka-martic-i-herojska-prica-o-pirgu/.

Toni Šimunović. “/Ne/poznati junaci iz pet ratnih romana” [“/Un/Known Heroes from Five War Novels”], Arena 6, no. 132 (July 5, 1963), 4-5.

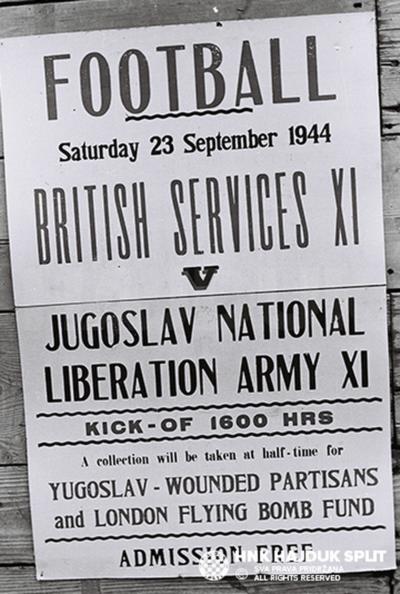

Football club Hajduk in the People's Liberation Struggle

In May 1944, Split football club Hajduk was renewed on the island of Vis, a military base used by the Partisans and the Allies since the capitulation of Italy in the fall of the previous year. The leadership of the People’s Liberation Struggle, Frane Matošić writes, wanted the Partisan army of Yugoslavia to have its own team. And the 26th division was stationed on Vis; in its ranks, since the capitulation of Italy, there were many players from Hajduk and other Dalmatian clubs. Training and occasional matches with teams of other Allied armies on the island were simply added to their military tasks.

Hajduk played several matches on Vis during the spring, but the biggest football spectacle took place in September 1944 in the Italian city of Bari, an important Allied port in the second part of the war. It was a match between the military football teams of Yugoslavia and Great Britain. Just as Hajduk’s team was made of professionals, the British team featured several football stars gathered from the battlefield and from the rear units and led by Stanley Cullis.

This match was played at the Stadio della vittoria in front of 50,000 spectators. Most of them were soldiers brought to the stadium by about a thousand trucks from the battlefield, nearby garrisons, and hospitals. Jug Grizelj, a publicist and journalist, wrote: “Despite the doctor’s strict prohibition, together with other 26 wounded men, I escaped from the hospital bed and went to the match. In hospital pajamas, on crutches, with bandaged heads, arms, legs... and the Stadium was full like a pomegranate...” In addition, British Army Broadcasting Service transmitted the entire game over the radio for those who had to stay at the front lines.

Played in difficult wartime conditions – in the peninsula, Pietro Badoglio’s government sided with the Allies, but Mussolini and the reformed Republican Fascist Party with the considerable help of German troops still ruled in central and northern Italy – this match (as well as other similar events) was conceived not only as a motivating force for soldiers/fans of individual teams, but as an event that encouraged friendship and further cooperation between different nations united against a common enemy. Boosting and bolstering the same spirit of togetherness, the two teams played a rematch in the liberated Split in the very end of 1944.

Photographs: Reproduced with the permission of the Arhiv HNK Hajduk (Archives of the HNK Hajduk), Split, Croatia.

Sources:

Jurica Gizdić, “Sjećanje na Bari 1944” [“Memory of Bari 1944”], HNK Hajduk Split, September 23, 2014, https://hajduk.hr/vijest/sjecanje-na-bari-1944-/5017.

Robert Kučić, Vis 1944.-2014. Dani časti, ponosa i slave 70 godina poslije [Vis 1944-2014. Days of Honor, Pride, and Glory 70 Years Later]. Split: HNK Hajduk, 2014.

Frane Matošić, “Split kroz povijest” [“Split throughout History”], Facebook, April 13, 2020, www.facebook.com/groups/454694734543441/permalink/3227044213975132/.

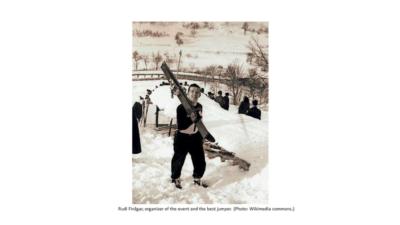

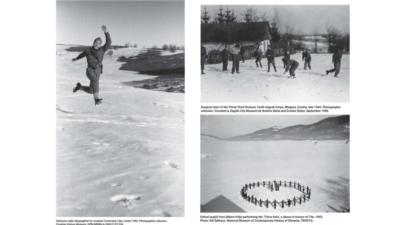

Snow 1

“The magic of the Plitvice Lakes bound by snow and ice was breathtaking,” Eva Grlić wrote in her memoir. She explained: “The landscape seemed like the enchanted, glittering courts of the Snow Queen. The waterfalls turned into the organ of icicles while the blue water could be seen under the ice. People crossed the frozen lakes with sleighs and horses. It was silent and beautiful as if there was no war. We found only members of the English military mission sightseeing. Nature did not recognize human adventures at all, it was and remains as majestic and inexorable as fate.”

Precisely the winters abounding in snow and ice proved to be inexorable for the Partisans to the greatest extent. Then the footprints threatened to reveal the routes they used and the locations of their bases. Its brightness revealed figures at great distances. And because of exposure to extreme weather conditions – particularly during long marches – the Partisans suffered serious health consequences, at times with fatal outcomes. A good example is certainly the case of the Slovenian dancer Marta Paulin – Brina (https://www.cmi.no/resource/1592-brina), who could no longer dance due to frostbite she suffered in the winter of 1944.

At the same time, the snowy weather could also provide an opportunity for children’s play even among adults. And, as the photo of the children in the circle testifies, in some cases children’s games were used as a testimony to the resistance of the entire community. Under the guidance of their teacher, the same children drew a five-pointed star and the name of the leader of the armed resistance, Tito, in the snow, both unifying symbols of the People’s Liberation Struggle.

Images: Davor Konjikušić, Red Glow: Yugoslav Partisan Photography, 1941-1945 (Berlin and Boston: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 2021), 224, 226, 229, 231.

Quote: Eva Grlić, Sjećanja [Memories] (Durieux: Zagreb, 1997), 108.

Further reading:

Kirn, Gal. “Was Dancing Possible during the Fascist Occupation of Yugoslavia?” Apparatus 11 (2020): 1-12. https://doi.org/10.17892/app.2020.00011.238.

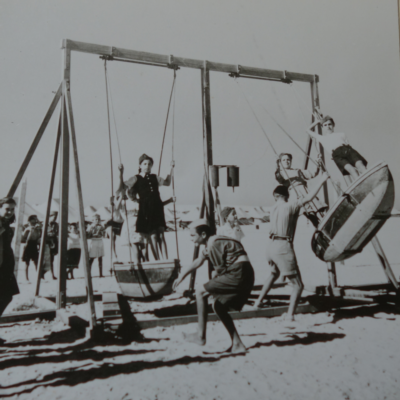

Living for a Better Future in the El Shatt Refugee Camp

In January 1944, the El Shatt refugee camp was established on the Sinai Peninsula. Following the Italian capitulation in September 1943 and in anticipation of the German invasion and reprisals, approximately 30,000 people from Dalmatia (southern Croatia) found refuge in the Egyptian desert. The representatives of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia, with war victory within reach, sought to organize and motivate their future citizens just like they did at home.

As the photos below show, these activities included organizing the lives of numerous children who found refuge in El Shatt, both their school and free time activities.

Pencils and paper were scarce and as a rule reserved for older school children. The youngest, therefore, had to learn how to read and write on the sand. The image shows children posing with the sign Naša škola (Our school) written on the sand.

In their free time, children could play on the swings that the residents of this camp made from driftwood.

Free time was often organized through various group activities, such as the athletics competition shown on the image.

You can hear more about life in El Shatt refugee camp on the WARFUN podcast here.

Photographs: UNRRA, UN Archives, Middle East – Social Life and Customs, S-0800-0008-0010

Further reading:

Bieber, Florian. “Building Yugoslavia in the Sand? Dalmatian Refugees in Egypt, 1944-1946.” Slavic Review 79, no. 2 (Summer 2020): 298-322.

Burić, Eli, “Zabilješke iz zbjega u El Shattu” [“Notes from the El Shatt Refuge”]. Kulturni radnik 8, no. 3-4 (1955): 108-111.

Nola, Danica. “Pionirsko kazalište El Shatt” [“Pioneer Theatre El Shatt”]. In Kultura i umjetnost u NOB-u i socijalističkoj revoluciji u Hrvatskoj [Culture and Art in the NOB and Socialist Revolution in Croatia], edited by Ivan Jelić, Dunja Rihtman-Auguštin, Vice Zaninović, 427-431. Zagreb: Institut za historiju radničkog pokreta Hrvatske, 1975.

Toys

Sisters Srbijanka (Joka) and Jovanka Bukumirović made for their children these three dolls - a boy with a puppy, Baba Jaga and an African warrior with an arrow - while they were imprisoned in the Banjica concentration camp (established in the Territory of the German Military Commander in Serbia in the summer of 1941). I thought for quite a long time about what to write about these toys. The problem appears even greater because the Museum of Yugoslavia, the institution that keeps these and a number of similar objects, does not have any information about the fate of their makers. It seems to me that my historian’s appetite for analyzing and explaining things, events, developments has no power here. However, Mitra Mitrović, who managed to escape from this camp, recorded bits and pieces about life within its walls. Capable to describe the lived experience of war with great care and tenderness, she noted the crucial in just a few sentences:

“It may be strange to someone what for the People’s Liberation Struggle mean these small things like: a doll, a cigarette box, [a box] for children’s pens, a cherry, a button, a sailboat, a piece of black velvet with a flower on it. On the eve of death itself, between the cold walls of the Banjica camp, joy was sought after for oneself and others. A miracle of beauty of the joy of life was made from a piece of silk. On a piece of silk and velvet, [...] I once again read the sad truth about my girlfriends, about gentle mothers who embroider their son’s pencil case, about girls who weave their dreams and youthful ardor into a slender female silhouette on the corner of men’s cigarette case or embroider a fine folk pattern on a doll’s clothes.”

Image: Reproduced with the permission of the Muzej Jugoslavije (Museum of Yugoslavia), Belgrade, Serbia. Further reproduction is prohibited.

Quote: Mitra Mitrović, Ratno putovanje [War Journey] (Belgrade: Prosveta, 1953).

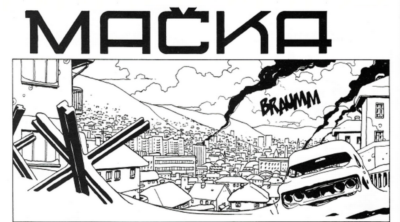

Games

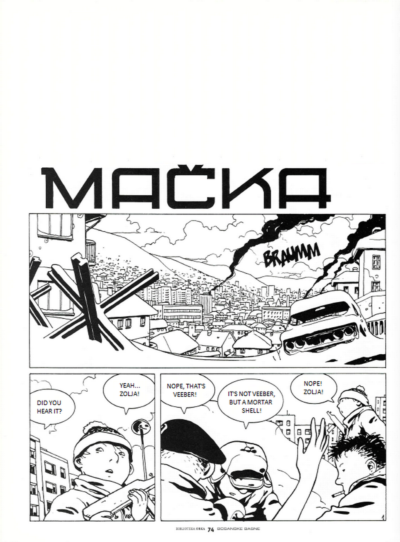

Two American fighter planes take off from their aircraft carrier stationed in the Adriatic. Their mission: surveillance and interception of possible aircrafts violating the airspace of Bosnia and Herzegovina. They fly over burned villages and towns, over camps hidden in the forests, over besieged Sarajevo. They do not detect any hostile activity in the area of operation. It is a rather calm day. But they do not see everything. For instance, what children do for fun in Sarajevo.

The pages showing children’s play, at the same time familiar and eerie, are just the beginning of the story “Mačka” (“Cat”) included in the comic book entitled Bosanske basne (Bosnian Fables).

Source: Lavrič, Tomaž. Bosanske basne [Bosnian Fables] (Zagreb: Naklada Fibra, 2006), reproduced with the author’s permission.

Translation: Iva Jelusic

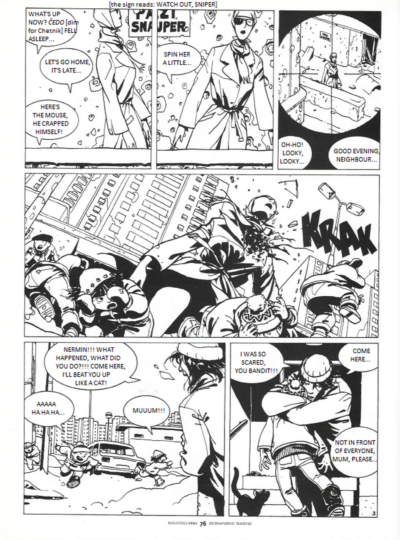

The Battle of Sutjeska in a Meme

World War II battles that happened throughout the Yugoslav countries between the Partisans and their rivals (that is to say, all other foreign and domestic and military-political options of the time) are still alive and kicking in the memories of the inhabitants of the successor states of socialist Yugoslavia. They are often the subject of (un)scrupulous historical research and public discussions. As the 2010 song (set in Croatian modernity) says: "And in the Parliament this morning, the same debilism / Whose old man was an Ustasha, and whose a Partisan."[1] Social networks, of course, contribute abundantly to the controversy. Occasionally a pearl (not necessarily of wisdom, but certainly of whimsy) appears. Right around the eightieth anniversary of the Battle of Sutjeska (May-June 1943), the attached meme - a completely new joke on an eighty-year-old topic - caught my eye in the wilderness of Facebook feed.

Some poet (as well as student of philosophy and jurisprudence, surrealist poet, communist volunteer in the Spanish Civil War, Partisan military commander during World War II, Chief of the General Staff of the Yugoslav People's Army, Minister of Foreign Affairs, and Vice President of Yugoslavia) - Koča Popović

Author of the meme - Stefan Gužvica

[1] T.B.F., Smak svita (The End of the World)

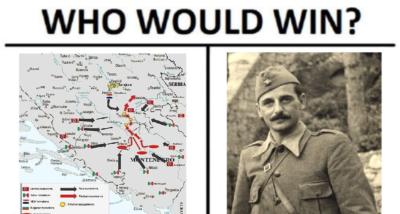

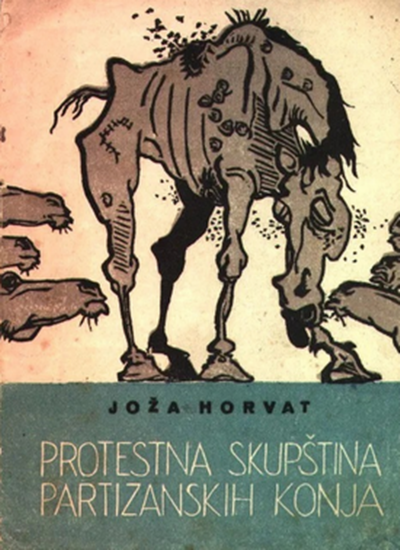

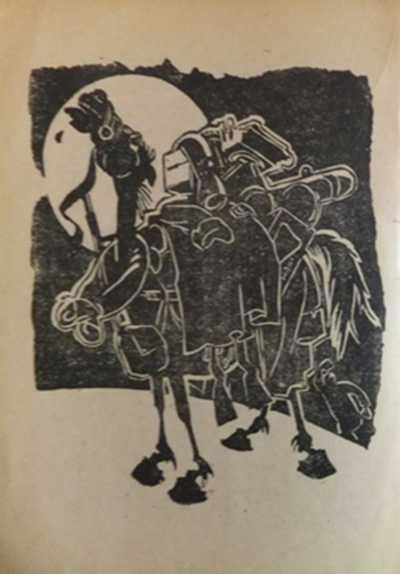

Joza Horvat's Protest Assembly of Partisan Horses (bonus part)

In the memoir literature about the Partisan People’s Liberation Struggle in Yugoslavia, horses are the most frequently mentioned animals. Often there are emotionally charged references to the crucial support provided by horses to civilians and soldiers on their wartime journeys. I have had a favorite little story about a Partisan horse for years now, so I will include it here as an illustration of the previous sentences. Then, I will turn to Joža Horvat’s 1944 booklet Protestna skupština partizanskih konja [Protest Assembly of Partisan Horses].

“My” story is about being wounded, and it is told by an unnamed Partisan soldier:

It hit me in both legs, and I fell off my horse. Zvrk was also wounded in the leg. He carried me and dragged me, holding my coat with his teeth, and little by little, limping, he dragged me to my comrades. They bandaged me, my bones were not injured, so I was sent to the hospital together with the lightly wounded. We also brought Zvrk. …

But you already know. What is a horse with three good legs? … They wanted to kill him with a pistol, but I didn’t let them. He was living in a plum orchard, I brought him bread and sugar, but his heart was breaking in his powerful chest at the sight of the expanses, which started right behind the fence. He collapsed one morning in that orchard, when his heart completely broke.

That’s how my Zvrk died quietly in the Partisan hospital, and I cried while digging his grave and burying him.

They said that I flipped because of a fall from my horse and because of the pain and fear, but, you see, I am completely normal.

It was completely normal for many participants of the Partisan struggle to care for their horses and grieve when the moment of parting came. But there were horses who, apart from the fact that they were often hungry and thirsty like their owners—and horses were regularly used as food when other food supplies were exhausted—also served as packhorses. They carried military commanders, the wounded and disabled, food supplies and kitchen utensils, as well as machine guns and ammunition. In general, they carried everything that could be loaded onto them.

In the name of all such horses, Horvat in his characteristic humorous manner wrote a short booklet. In it, following the numerous different assemblies held by the Partisans and their supporters throughout the war, the horses decide to hold theirs to complain about their misfortunes. One of the present horses explains: “In the brigade, I no longer look like a horse. They turned me into a two-humped camel, loaded on me everything and anything, and how they feed us and give us water, you have already heard from my precursors.”

As if carrying all the cargo was not enough, the horse complained—that is, the author mocked: “Partisans … throw their cloaks on us, hang rifles, purses, and flasks, and while we squirm under the burden, they walk beside us and sing songs.”

Although the booklet Protest Assembly of Partisan Horses was written in a way that would entertain the Partisans and make them laugh, it also had an educational dimension. At the very end, the author advised all the readers not to beat their horses, and to take care of their nutrition and cleanliness, if for no other reason than to prevent such an assembly of horses from taking place again.

Illustrations in the booklet: Vlado Kristl.

Bibliography

Horvat, Joža. Protestna skupština partizanskih konja [Protest Assembly of Partisan Horses]. Crna Lokva na Petrovoj gori: Naprijed, 1944.

Ribnikar, Jara. Život i priča I-II [Life and Story I-II]. Belgrade: Prosveta and Srpska književna zdruga; Sarajevo: Veselin Masleša; Zagreb: Mladost, 1986.

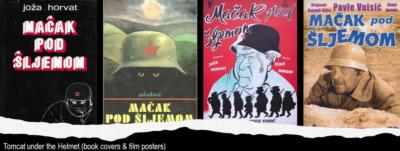

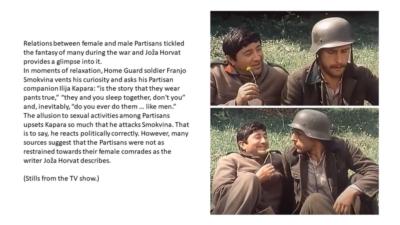

Joza Horvat's Tomcat under the Helmet (part 1): On Soldier Humor

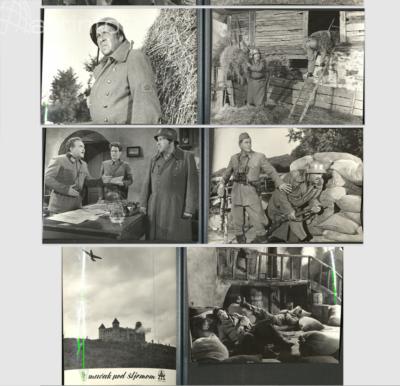

The writer Joža Horvat, inspired by his own experiences of partisanship, wrote about the Yugoslav Partisan war in his 1962 comic novel Mačak pod šljemom [Tomcat under the Helmet]. It became an exceedingly popular novel that was adapted into a film during the same year, and then into a television series in 1978.

The plot of the novel is grounded in real World War II events that took place in the north of Croatia. In September 1944, the imaginary 32nd Partisan Division descends from Mt. Kalnik to the county of Zagorje to sow confusion in the enemy ranks around Zagreb. The figure of Ilija Kapara, “corporal of the first squad of the first platoon of the first company of the first battalion of the First Shock Brigade of Kalnik,” stands out.

Kapara is an unwilling hero as well as an inventive and cunning Partisan “tomcat.” He is also the possessor of a prickly sense of humor; in that, he is not unlike his creator, who was inconvenienced by it more than once. Importantly, Kapara is the first literary Partisan soldier whose sense of humor presents his principal weapon in his daily contest with death. His is a familiar type of military humor; it is often considered exaggerated, inappropriate, and rude, and as such had found no place in most published materials about Yugoslav Partisan warfare.

For instance, after his first battle in the Partisan ranks, during which he had shot two enemy soldiers, Kapara feared that he would have nightmares about the men he had killed. Comforting the trembling soldier, the unit commander assured Kapara that he would certainly not dream of them and that he should rather concentrate and shoot at least two more men the following day! In September 1944, as a result, when he overpowers an Ustasha soldier with a knife, Kapara jokes with ease that “they can now blow up the ass of the guy in the hayloft, the air will come out of his back.” The Home Guard soldier, in whose company Kapara is at that time, exclaims in amazement: “Slaughtering a man to you is like letting out a fart to a child!”

The most interesting thing about Tomcat under the Helmet is that, although civilians commonly find it difficult to accept the sharpness of military humor, when the book was adapted and appeared on television, the people who felt most offended were the Partisan veterans. They complained to Zagreb television that the author of the book had tarnished the reputation of the Partisan struggle during World War II. In the section which seems to have upset them the most, Horvat—quite gently—mocked the partisans’ “provenance.” Specifically, he wrote that there were Partisans who got involved in the war completely by chance—for instance, because they wanted to escape their overbearing wives or because they did not want a girl to see their dirty underwear, as was the case with Kapara’s comrade Vodenjak. Recounting the common fate of many a Home Guard soldier—that in Partisan captivity they could choose to return home only in their underwear or to keep their clothes and weapons and become Partisans—he explained to his comrades:

And that’s how it started, some [soldiers in his Home Guard unit] took off their clothes, some stayed, and all this was watched by the Partisans, and not only Partisans, but, as I said, by the whole village, women, old people, children …. Near me was a pretty village girl, as rosy as an apple. That girl made me sweat. The time to decide was getting closer and closer, I’d like to go home, but I know that my underpants are smeared and torn, I’m going to burn with shame! What should I do, what should I do?! That girl is looking at me, I’m looking at her, and all I can think of are my damned Home Guard shorts and I’m sweating. And when it was my turn to stay or to take off my pants, I raised my hand and shouted in despair: – Comrade, I am yours …

To answer the Partisan veterans’ angry letters, Zagreb television arranged a guest appearance by Joža Horvat himself. The author explained to all who felt offended by his novel that he had spent time with and fought with soldiers who were just like those he wrote about. More importantly, he explained that soldiers such as Ilija Kapara and the men in his squad had successfully resisted all difficulties precisely because they were armed with more than just rifles and bombs. Their superpower—just like the author’s—was, of course, humor.

(source: https://artinfo.ba/index.php/zanimljivosti/32209-macak-pod-sljemom-kiseljak-kao-filmska-kulisa-i-prva-crta-bojisnice)

Bibliography

Horvat, Joža. Mačak pod šljemom [Tomcat under the Helmet]. Zagreb: Naprijed, 1989.

Sabljak, Tomislav. “Humor i lirizam Jože Horvata” [“Joža Horvat’s Humor and Lyricism”]. Mogućnosti 10 (1962): 947–952.

“Joža Horvat – književnik i moreplovac” [“Joža Horvat – Author and Seafarer”]. Accessed: June 14, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e6pTA1eyXTw.

Joza Horvat's Tomcat under the Helmet (part 2): On the Home Guard

Dr. Julka Mešterović recorded in her wartime diary the following exchange between the famous Partisan commander Koča Popović and an unnamed colonel of the Home Guard:

Popović: Do you know that we captured your entire regiment with two Partisan battalions?

Colonel: I know. (…) If you were the commander of my army, and I of yours, I would also perform miracles.

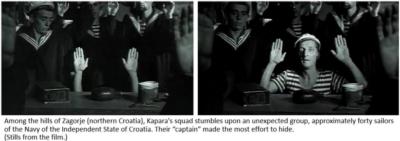

Mešterović interprets the fact that two units of Partisan soldiers won a victory over a group of Home Guard soldiers over twice as numerous as proof of the heroism of her comrades. However, the fighting value of the Home Guard—the conscripted land army of the Ustasha-led Independent State of Croatia—was, according to their German allies, always low. And according to the Partisans, it was often so low as to be laughable. As funny and sometimes likeable cowards, the soldiers of the Home Guard entered the cultural memory of the Second World War in Yugoslavia.

A little in his memoir Witness to Transience and much more generously in the novel Tomcat under the Helmet Joža Horvat mocked them. Remembering the group of captured Home Guards, in his memoir Horvat describes them as a huddled herd of frightened sheep. As the unit’s political commissar, he spoke to them about the importance of Partisan warfare, mostly in relation to the crimes of the occupying armies. And they, he wrote, stared at him almost bleating. Maybe they were the inspiration for the scene of the capture of the Navy unit in the hills of Zagorje or the character of the Home Guard soldier Franjo Smokvina who encounters Ilija Kapara, the protagonist of Tomcat under the Helmet, in the hayloft of an unnamed village in Zagorje county. The author describes the intensity of Smokvina’s fearfulness when he finds out that Kapara is a Partisan:

Poor human heart! Poor timid Home Guard heart! It almost stopped, it almost stopped beating. For the second time in these few minutes, he jumped out of the hay, startled, not knowing what to do. To flit like a bird and fly away from the hayloft, to turn into a mole and bury itself and disappear forever?

Smokvina stays with Kapara. He has estimated that his chances of survival are better that way, at least until he gets closer to his native village, where he can then hide. In the end, however, like many other members of the Home Guard (for example, Vodenjak, mentioned in Part 1), Smokvina himself becomes a Partisan. That is, in the novel, one of the countless cowards from the county of Zagorje, laughed at due to their fearfulness, becomes a soldier of the heroic liberation army. And in reality, Horvat managed to convince eight members of the Home Guard belonging to that group of frightened sheep to join the Partisans.

Bibliography

Horvat, Joža. Mačak pod šljemom [Tomcat under the Helmet]. Zagreb: Naprijed, 1989.

Horvat, Joža. Svjedok prolaznosti [Witness to Transience]. Zagreb: Neretva, 2005.

Mešterović, Julka. Leakrov dnevnik [The Doctor’s Diary]. Belgrade: Vojnoizdavački zavod, 1968.

Skrigin, Žorž, dir. Mačak pod šljemom [Tomcat under the Helmet]. Sarajevo: Bosna film, 1962. DVD.

Joza Horvat's Tomcat under the Helmet (part 3): On Women

In the novel Tomcat under the Helmet, Joža Horvat writes about women from the perspective of the male Partisans. It is well known that approximately 100,000 women served in the Partisan army; Jelena Batinić calculated that the percentage of women in Partisan units was at times as high as twenty percent, with an average of about ten percent. Although Horvat, through the mouth of Ilija Kapara, the protagonist of the novel, readily defends the women who joined the army—drugarice (female comrades)—he does not include any of them among the characters in the novel. Yet he finds some room for a few civilian female characters, most notably Lenka, the kafanska pjevačica (tavern singer).

Following the arrival of the Partisan brigade to which Kapara’s squad belongs at the village of Zelena Mrkvica, a few men visit the local tavern in search of something to eat. One of them, nicknamed Brico, pretends to be a doctor in order to visit the reportedly indisposed singer Lenka. As expected, Brico later boasts to his squad about his supposed conquest. The conversation nicely outlines the prevailing attitudes of the time about men and women in an almost charmingly funny way. To preserve the nuances of humor as much as possible, instead of retelling the sequence, I have translated the conversation between Brico and his comrades.

Squad member: Did she believe you were a doctor?

Brico: Why wouldn’t she believe it? It isn’t written on anyone’s forehead.

Squad member: And she didn’t defend herself?

Brico: I did not attack her so that she would have to defend herself. I also had money if she wanted.

Squad member: She didn’t ask for it in advance. And later?

Brico: Not later either.

Squad member: I guess she knew that the Partisans are poor …

Brico: I won her over, that’s the thing … And she knows her job, the beast! If they hadn’t driven us out of [Zelena] Mrkvica, I would have visited her a couple more times.

Squad member: What’s her name?

Brico: Lenka.

Squad member: And she didn’t say anything at all?

Brico: What would she say?

Squad member: I mean … She must’ve said something!

Brico: Well, she did … she said something. When everything was done, she got up, put on her clothes, stood in front of the mirror, combed her long black hair, combed it, combed, then suddenly she laughed, turned to me, and said: “I didn’t know that medical service in your brigade was so well organized. You’re the third doctor who has examined me this morning …!”

Squad member: What a bitch!

Squad member: She made that up!

Squad member: Why would she make it up? Three out of the whole brigade, that’s not that much.

He [Kapara] did not make it. He could not take it anymore. Somewhere on the border between envy and seniority, [political] awareness awakens in Kapara: You, Brico, stop! You’re embarrassing the brigade!

Brico: Why would I embarrass [it]?

Kapara: That is not worthy of a soldier of the people’s army. You will hear from the political commissar!

Brico: What’s not worthy?

Kapara: That … She’s a whore!

Brico: Of course she’s a whore, that’s why I went to her. To whom should I go—to an honest woman? The women in the brigade, women comrades, you cannot even look at them, let alone touch them, you are not allowed, and they don’t feel like it, and it’s not my fault that I’m like a little calf—I have to be between someone’s legs!

The squad bursts into laughter and Kapara feels that he has lost the battle. He is comforted by the thought that he will get satisfaction at the company meeting.

The author provides a bit more military sexist humor through the character of the Home Guard soldier Franjo Smokvina (mentioned in part 2).

In addition, Smokvina, otherwise an exemplary coward and a deserter from his army, cheerfully suggests to Kapara that instead of lunch, the two of them could “do” a civilian woman whom they met by chance while travelling through a forest—“She is ugly ... but still,” Smokvina jokes; “In my village, a hairy woman and a short-haired mare are the most expensive!”—suggests that much of the soldiers’ sexist humor and their dispositions toward women remains unmentioned.

Bibliography

Batinić, Jelena. Women and Yugoslav Partisans: A History of World War II Resistance. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Horvat, Joža. Mačak pod šljemom [Tomcat under the Helmet]. Zagreb: Naprijed, 1989.

Makarović, Berislav, dir. Mačak pod šljemom [Tomcat under the Helmet]. Zagreb: RTV Zagreb, 1978. DVD.

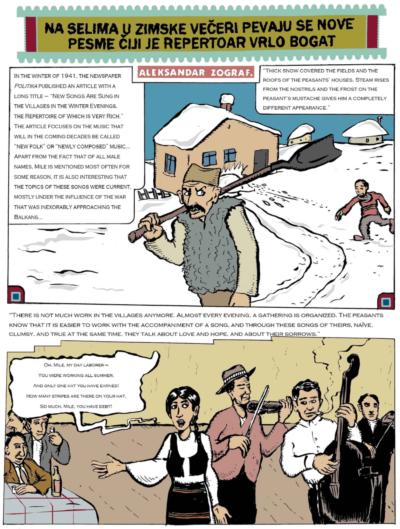

"New Songs are Sung in the Villages in Winter Evenings, the Repertoire of which is Very Rich" (Partisan Circle Dances, part 4)

Despite the efforts of the Yugoslav partisan leadership and cultural workers to inspire their supporters, both civilians and partisan soldiers, to sing about themes motivated by and closely related to the struggle (as presented in the first two posts of Partisan Circle Dances cycle), people never stopped creating songs about the things that moved them the most. Something on this topic was presented in the previous, third post of this cycle, and something will be presented in this one as well, but from the perspective of the Serbian comic artist Saša Rakezić, who is better known by his pen name Aleksandar Zograf.

Source: Priče iz drugog rata (Stories from the Second War) (Belgrade: Popbooks/Muzej Jugoslavije, 2022), reproduced with the author’s permission

More about Aleksandar Zograf and his work: https://www.aleksandarzograf.com/

Translation: Iva Jelusic

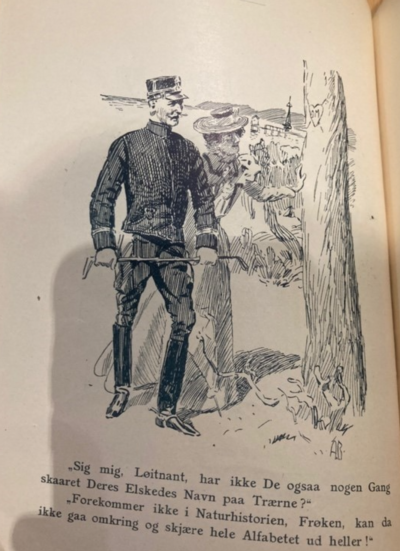

Gendered military satire in Norway

Image: From Bloch, A. (1906) Præsenter gevær! Militærhumoresker fra korsaren. Kristiania: Korsarens Forlag. Sourced from the Norwegian Armed Forces Museum, Oslo.

The woman: ‘Tell me, lieutenant, haven’t you also carved your lover’s name on a tree?’

The cavalry officer: ‘That would never happen in “naturhistorien” [the history of nature]. My lady, I cannot possibly walk around and carve out the entire alphabet.’

As soldiering is a male-dominated profession, it is no wonder that military satire tends to be deeply gendered. However, like other humor genres, satire can be both inclusive and exclusionary, reinforcing or undermining engrained stereotypes and inequalities. I took the picture above when reading a military humoresque book published in 1906 (Bloch 1906) that I found at the special library of the Norwegian Armed Forces Museum in Oslo. The librarian explained to me that cavalry soldiers were often subjects of mockery and ridicule. Their military specialization entailed many expenditures, and in the seventeenth century, many struggled economically. However, the cavalry soldiers were regularly depicted as self-absorbed, superficial, and stupid people who put themselves in debt to buy expensive uniforms and horses. They were also described as kvinnebedårere (womanizers) who cared more about themselves and their horses than their wives.

Fast forward to present-day Norway, and military satire still draws upon gendered stereotypes, yet in different and occasionally more subversive ways. A good example is Førstegangstjenesten (The Conscription Service), a popular sketch comedy TV show created by the comedian and Instagrammer Herman Flesvig that began airing in 2019. The show centres around four main characters, all played by Flesvig: a war enthusiast, a spoiled graduate, a white wannabe gangster rapper, and a ‘female male chauvinist’. That last character, Tanja Laila Gaup, is a brusque and vulgar young woman from Northern Norway who is far stronger and coarser than the male conscripts. Throughout the show, she caricatures and destabilizes gendered and military norms and stereotypes through, for instance, displaying force and violence, sexually harassing male soldiers, and trying to conceal her own emotions.

In the show’s second season, we also learn that Tanja Laila is the only character who passed the selection for the special forces. It is hard not to read this as an intervention into ongoing public debates concerning the role of women in the Norwegian Armed Forces. Despite official targets and ambitions, women still make up only a small, albeit growing, minority in the Norwegian war force (Stai et al 2021). However, besides the all-female special forces training programme Jegertroppen (Hunter Troops), no woman has ever been selected for the special forces. While some have objected to this and called for greater inclusion and gender quotas, others argue that introducing quotas is detrimental to the operational strength and capacity of the Norwegian war force, and the special operation forces in particular (see e.g., Høiback 2016). The debate has raised questions of not only military skills and biology, but also what it means to treat men and women (un)equally within the Armed Forces and whether or not the latter’s representation should be regulated by political ideals and ambitions of gender equality. Norwegian ethnographers studying all-male combat units have added to the debate by showing that female participation is not merely a question of physical capacity; women are also commonly described as potential threats to male asexual cohesion and solidarity (Danielsen 2018; Totland 2009). Finally, there have been multiple reports and accounts of sexual harassment in the Norwegian Armed Forces in recent years, with some suggesting a culture of impunity exists.

Førstegangstjenesten, and the character Tanja Laila in particular, address these debates by exposing and (at times) subverting gendered military norms and narratives. The show has succeeded in making many Norwegians laugh, but also invites the audience to question their preconceived ideas about masculinity, sexuality, and violence.

References

Bloch, A. 1906. Præsenter gevær! Militærhumoresker fra korsaren. Kristiania: Korsarens Forlag.

Danielsen, T. 2018. Making Warriors in a Global Era: An Ethnographic Study of the Norwegian Naval Special Operations Commando. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

Høiback, H. 2016. Forsvaret: et kritisk blikk fra insiden. Oslo: Cappelen Damm.

Stai, N. K., Rødningen, I., Olsson, L., and Tollefsen, A. F. 2021. ‘Breaking Down Barriers for Norway’s Deployment of Military Women’. GPS Policy Brief, 1. Oslo: PRIO.

Totland, O. M. 2009. ‘Det operative felleskapet. En sosialantropologisk studie av kropp, kjønn og identitet blant norske soldater i Telemarksbataljon’. Masters thesis, Institute for Social Anthropology, University of Oslo.

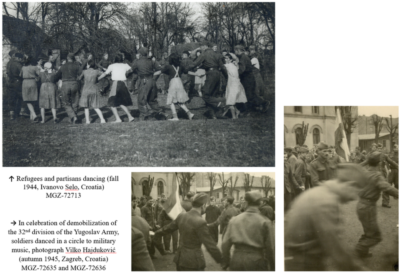

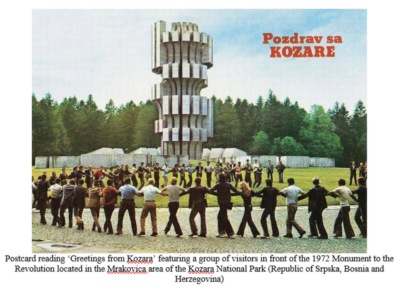

Partisan Circle Dances (part 3)

When they discuss circle dances, historical sources of the Yugoslav partisan war most often mention the Kozara circle dance. Equally as often, they emphasize rhyming folk couplets on war and political topics as the music that accompanied the circle dances (as explained in part 1). It is important to mention, however, that there were many variations of the circle dance, and that the topics for the couplets that were popular in peacetime remained so during the wartime too, especially in more relaxed or unsupervised settings.

The best example is provided by Eva Grlić, who spent most of her partisan life in Slavonia (eastern Croatia). One evening, with the intention of cheering her up, a friend took her for a walk through the forest to a clearing where a group of young people were dancing, illuminated only by the moon. “There was something magical in that scene of dance in the moonlight. […] To me it seemed like a pure surrealism,” Grlić noted in her memoir. Young women and men danced the taraban circle dance and sang:

It is easy to dance taraban

Jump up, and on your own you will go down.

and

Girls, come to me

Before the women have caught me.

This short fragment from Eva Grlić’s memories of war hints at a relevant aspect of life in the partisan army: although the partisan military authorities prohibited romantic relationships among partisans, particularly what we today call hooking up, they never succeeded in eradicating it. If nothing else, many covertly whispered about love, sex, relationships, and marriage, talked and even sang about it. A series of rhyming couplets with which the mischievous participants expressed their thoughts on the restrictive partisan policy remained:

Leave love alone, my sweetheart

And go fight for people’s right.

When our country is free again

Return and make love then.

-----

When I remember your face, my dear

I forget about my commander.

-----

The girls are begging you, comrade Tito,

Let the boys go.

For two, three days or five, six hours at least

And then return them to the brigade forthwith.

Translation of the couplets: my own.

Author of the illustration: Dario Jelušić.

Bibliography:

Bošković-Stulli, Maja. Petokraka, zašto si crvena: narodne pjesme iz ustanka (Five-pointed Star, Why Are You Red: Folk Poems of the Uprising). Zagreb: Lykos, 1959.

Grlić, Eva. Sjećanja (Memories). Durieux: Zagreb, 1997.

Rihtman-Auguštin, Dunja. “Folklor kao komunikacija u NOB” (“Folklore as Communication during the NOB”). In Kultura i umjetnost u NOB-u i socijalističkoj revoluciji u Hrvatskoj (Culture and Art in the NOB and Socialist Revolution in Croatia), edited by Ivan Jelić, Dunja Rihtman-Auguštin, Vice Zaninović, 151–166. Zagreb: Institut za historiju radničkog pokreta Hrvatske, 1975.

Partisan Circle Dances (part 2)

Following the launch of both the airborne and ground assault on the city of Drvar (eastern Bosnia and Herzegovina) in May 1944, the VIII partisan corps retreated to Jadovnik mountain. Despite the units of the German army being on their heels, at night, while the units were resting to prepare for a new day of fighting, the partisans partly walked and partly rolled down a goat trail that led to the foot of the mountain. The next day, the German soldiers searched the territory where the VIII corps had previously stayed. They then searched possible routes of retreat, but not the path by which the partisans left. It is assumed that either they did not notice the sad excuse for a retreat passage or did not think that the partisans would actually dare to use it in the dead of the night.

German units left Jadovnik. The following night, after an almost all-night hike, the partisans returned. The location that was teeming with enemy soldiers the day before was now completely safe. They were alive and, at least temporarily, out of harm’s way. So, as soon as they returned, Žorž Skrigin claims, they got into a circle and danced. He snapped a photo.

Source:

Žorž Skrigin, Rat i pozornica (War and Stage). Belgrade: Turistička štampa, 1968, 255–261, photographs on 256 and 257.

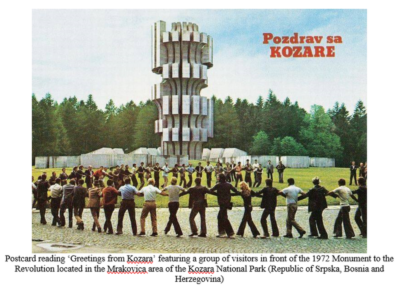

Partisan Circle Dances (part 1)

Hey Kozara, hey Kozara, my thick woodland

You are hiding, you are hiding many a partisan.

How many, hey, how many are there on Kozara tree branches

There are even more, hey, even more young partisans.

How much, hey, how much is there on Kozara leaves

There are even more, hey, there are even more young communists.

These are some of the most famous verses sung by the Yugoslav partisan soldiers and their supporters during World War II. Their foundation is a short rhyming couplet appropriated from the popular folklore form known as bećarac. Every rhyming couplet is one unit, one independent poem. If the couplets had a similar theme, singers would sometimes put them together in order to create a new, longer poem, and sometimes singers omitted the couplets that, for instance, they could not remember.

The couplets acted as poetic comments on all life experiences, in both peace and war. The brevity of the couplets and familiarity of their form made it possible for everyone to understand the gist and participate in their further dissemination.

Partisan commentators thus established that:

Our struggle demands

That one sings when one dies.

Women partisans often sung:

Who could've known last year, comrades,

That girls would become partisans.

or

I’m your only daughter, oh, mother of mine

I am leaving you to carry a carabine.

Of course, daily news – such as the standoff of the Nazi army before Stalingrad or the capitulation of Italy – were regularly commented on:

Hey Hitler, what the hell,

Why does your army stall?

Either you can’t, or winter has met you,

Or the Russian offensive beats you.

and

Rejoice, brothers partisans

Italians by themselves gave up their guns.

Partisans sang these kinds of songs in their free time, on the march, and in the military hospitals, either in the darkness of their hospital rooms lying on their improvised, often straw beds, or in groups while enjoying fresh air – maybe even some sun – in front of the hospitals. However, they were most often sung while soldiers as well as civilians held hands and moved to the rhythm of singing.

The movement was, of course, a circle dance, probably the oldest dance formation common to many cultures. It was most often performed in a semicircle or a curved line to musical accompaniment while the person at the head sang the verses that the rest of the group then repeated. One participant of the war told the Slavist and folklorist Maja Bošković-Stulli that “When I was in a circle, I would invent and sing, I would sing both my own and other people’s [verses]. I was a part of the people. We were all one then, we fought and sang.”

The couplet and the circle dance – particularly the variation that became known as the circle dance of the Kozara mountain – became a means of communication during the war that strengthened the fighting community and encouraged their togetherness and perseverance. Their symbolic role has also become part of the cultural memory of the war.

Translation of the couplets: my own.

Photographs 1–3: Muzej grada Zagreba (Zagreb City Museum), Collection Militaria

Photograph 4: Spomenik database, https://www.spomenikdatabase.org/kozara

Bibliography

Bošković-Stulli, Maja. Petokraka, zašto si crvena: narodne pjesme iz ustanka (Five-pointed Star, Why Are You Red: Folk Poems of the Uprising). Zagreb: Lykos, 1959.

Bošković-Stulli, Maja. “Narodna poezija naše oslobodilačke borbe kao problem savremenog folklornog stvaralaštva” (“Folk Poetry of Our Liberation Struggle as a Matter of Contemporary Folklore Creation”). Belgrade: Etnografski institut Srpske akademije nauka, 1960.

Rihtman-Auguštin, Dunja. “Folklor kao komunikacija u NOB” (“Folklore as Communication during the NOB”). In Kultura i umjetnost u NOB-u i socijalističkoj revoluciji u Hrvatskoj (Culture and Art in the NOB and Socialist Revolution in Croatia), edited by Ivan Jelić, Dunja Rihtman-Auguštin, Vice Zaninović, 151–166. Zagreb: Institut za historiju radničkog pokreta Hrvatske, 1975.

Bela, the actress

Miroslav Krleža is widely considered the greatest Croatian writer of the 20th century. However, immediately following the establishment of the Nazi puppet Independent State of Croatia (Nezavisna Država Hrvatska, NDH), his works were banned and, after spending a few days in Ustasha prison, the author went into isolation. Sick, anxious, and inclined to the usage of barbiturates, in those years he devotedly nursed his own ego in the pages of his diary. The left-wing writer did not change his position throughout the war, although the Ustasha leadership gradually eased pressure on him. The author even got the opportunity to say no to Ante Pavelić, the head of the NDH, who in the fall of 1943 wanted to hire him as director of the Croatian State Theater in Zagreb.

Miroslav Krleža wallowed in his misfortunes thanks to influential colleagues and friends and his wife, Bela Krleža, who performed in the very theater where he refused to work. Her professional compromise – which, given that she was a Serbian, could have been fatal for her – provided them with insurance against political persecution as well as existential security (for the second time during their marriage).

In his diary, Miroslav mocked the pretentiousness of the life of the Zagreb bourgeoisie as well as their seeming obliviousness to grim wartime reality. And Bela was not spared a little of his pity because, he writes, during the war she became “an actress in the bureaucratical sense, de facto acting in some horrible things.” Namely, the plays in which his wife performed were by and large lighthearted, escapist comedies with romantic overtones – for instance, she acted in the adaptation of A Friend of Women (L’Ami des femmes, 1864) and The Lady of the Camellias (La Dame aux Camélias, 1848) written by Alexandre Dumas fils and in the pastoral Plakir (1556) written by one of the most celebrated Croatian Renaissance authors, Marin Držić – intended to amuse and please those people that her husband mocked as well as the members of the leadership of the state, which both had reason to fear.

Since she was one of the most active actresses during the war years, Bela Krleža was exposed to enormous publicity. Moreover, she was loved by both audiences and critics. And when, in the fall of 1945, her colleagues faced the so-called court of honor, she was most probably saved from political persecution by her husband’s war silence and his postwar reconciliation with the leadership of the Yugoslav Communist Party.

Photograph: Scene from the pastoral Plakir, May 1943; Bela Krleža is third from the right

Owner of the photograph: Croatian State Archive (Hrvatski državni arhiv, HDA), Collection of theater photography of Mladen Grčević (HR-HDA-1424)

Bibliography:

Banović, Snježana. “Bela i Miroslav Krleža u NDH - Vedri repertoar kao cijena za život” (“Bela and Miroslav Krleža in the NDH - Bright Repertoire as the Price of Life”). In Intelektualci i rat 1939.-1947.: Zbornik radova s Desničinih susreta 2011. (Intellectuals and the War 1939–1947: Proceedings from the Meetings of the Desnica’s Gatherings in 2011), edited by Drago Roksandić and Ivana Cvijović Javorina, 9–24. Zagreb: Filozofski fakultet u Zagrebu, 2012.

Banović, Snježana. Država i njezino kazalište: Hrvatsko državno kazalište 1941. – 1945. (The State and Its Theatre: Croatian State Theatre 1941–1945). Zagreb: Profil, 2012.

Krleža, Miroslav. Dnevnik 3 (1933.-1942.) (The Diary, volume 3 (1933-1942)). Sarajevo: Oslobođenje, 1977.

Krležin gvozd. “Bela Krleža – televizijski prilog povodom obljetnice rođenja” (“Bela Krleža – Birth Anniversary Television Contribution”). Accessed September 21, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5kU8rKN25DQ.

Puljizević, Jozo. “Jedna biografija - sto života: Bela Krleža o sebi i Miroslavu Krleži” (“One Biography – A Hundred Lives: Bela Krleža about Herself and Miroslav Krleža”). Vjesnik u srijedu (July 4, 1973): 24-26.

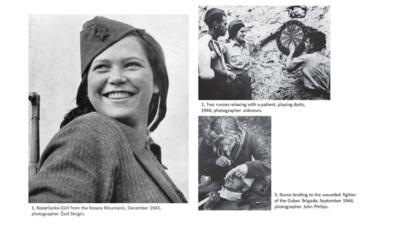

Ina, the poet

Remembering the moment when perhaps the most famous photograph of the People’s Liberation Struggle, “Kozarčanka” (Girl from the Kozara Mountain), was taken, one-time partisan nurse Milja Marin said:

“Even today, I don’t know how that smile in Skrigin’s photograph appeared on my face. I gave in to my emotions, although I did not feel like laughing, but I believed that my personal suffering at that time and the suffering of my family must come to an end.”

Indeed, the everyday challenges faced by nurses in the Yugoslav partisan army were numerous and draining because, as Ina Jun Broda, another wartime nurse, explained, to both doctors and the wounded soldiers the nurses “represented something between the ‘mother of God’, the self-sacrificing comrade and the ‘hospital bedpan’.” As a well-educated woman particularly inclined to poetry, Jun Broda expressed her weariness, her grief and compassion, but also the irony and mockery she sometimes felt in writing. The poem “Samokritika” (“Selfcriticism”) captures this combination of emotions well:

I confess, comrades, it is my fault.

It is my fault that I survived every assault

While the comrades died on the mountain peaks,

I still have all my limbs.

I confess, comrades, it is my fault:

I still don't know when was the third assault[1]

Because, during the political course,

I escaped to the park through the hospital doors.

I h a d to for a while be alone!

I enjoyed the evening's dark tone…

A petit-bourgeois song rising from my chest was so nice and fine

Yet it certainly was not along Party line...

Comrades, I confess that it is my fault

I sinned against the collective.

It is horrible: I would like to have my own home, my own dreams,

My own toothbrush,

my own shoelaces,

my own shoes –

my thoughts…

my comrade and his embrace

and my child…

I know, it is not right

because of my kid

to forget our orphans and their afflict

But I know that I would love that son of mine

even more than the Red Army and Stalin at the same time!

Sitting under Tito’s photo until late last night

I spoke to our hateful ally.

Joe is good and humble, honest and kind

And o u r s. But wounded – he was wounded only two times!

Three years of fighting and still head on his shoulder!

I don’t know, maybe he is not such a devoted soldier?

And so, comrade Commissar, I would like to be informed

Did I sin against our norms...

That’s all. Now let the comrades decide

So be it as they derive.

If I’m guilty, liquidate me.

Put a bullet through my head simply.

Perhaps it was meant to be –

The real consciousness, the new, has not yet been awakened in me

I’m confused and I have no one else to blame but me:

I still don’t know, comrades, how to live.

Should I follow fervor or head – a new blind allegiance

or the old compliance?

Cold discipline or my own ardor,

My heart or instead – the revolver???!

It is too hard, comrades, that’s why I said:

Bullet in the head. – But when they put me in front of a wall

once again I will boldly exclaim:

Death to fascism!!! – and freedom, freedom, freedom

for woman!

Translation: my own.

Poem: Samokritika is a part of Ina Jun Broda's wartime diary. It’s retyped contents, entitled Iz moje Crne bilježnice (From my Black Notebook), are kept in her archival collection at the archives of the Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts.

Illustration no. 1: Žorž Skrigin, Rat i pozornica (War and Stage) (Belgrade: Turistička štampa, 1968), 248.

Illustrations no. 2 and 3: Davor Konjikušić, Red Glow: Yugoslav Partisan Photography, 1941-1945 (Berlin and Boston: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 2021), 214, 319.

Literature:

Kovačević, Dinka. “Mlada partizanka iz čitanke” (“Young Partizanka from a Textbook”). Nezavisne novine, June 8, 2007. http://www.nezavisne.com/novosti/bih/Mlada-partizanka-izcitanke/10554.

Bakšić, Lucija, Grubački, Isidora, and Jelušić, Iva. “Ina Jun Broda.” In Texts and Contexts from the History of Feminism and Women’s Rights in East Central Europe, edited by Zsófia Lóránd, Adela Hȋncu, Jovana Mihajlović Trbovc, and Katarzyna Stańczak-Wiślicz (forthcoming in 2023).

[1] The poet refers to the Third Enemy Offensive, one of seven major Axis military operations undertaken against the Yugoslav partisans during World War II, happening in the spring and early summer of 1942 in eastern Bosnia and in Montenegro.

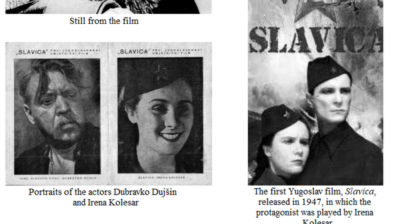

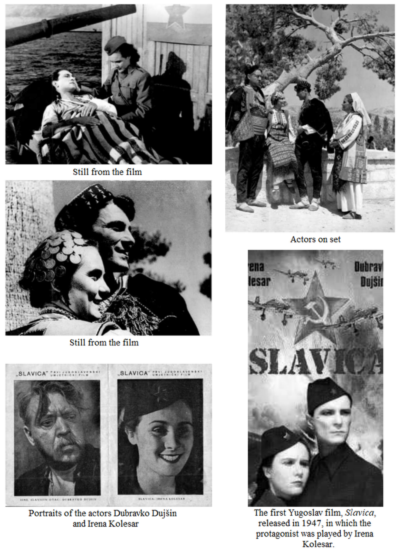

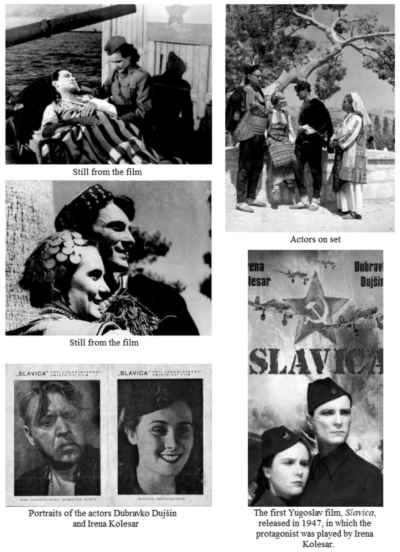

Irena, the actress

In the summer of 1943, Irena Kolesar joined the Yugoslav partisans. Having caught the eye of Šime Šimatović and Joža Gregorin, members of the theater group that was visiting her unit, she was invited to an audition. She spent the rest of the war acting in several major theater groups (and continued her successful acting career after the war ended).

In a 1972 interview for the Yugoslav magazine Start published in Zagreb, Kolesar testified to a common aspect of partisan life: “When things were most difficult for us, we sang. No one believes us today (…).” But many memoirs bear witness to singing in the most unexpected, oftentimes grim and difficult moments.

Irena Kolesar’s recorded memories also reveal an unsurprising but barely mentioned aspect of officially organized entertainment of the partisan war – that artists were usually bored by their assignments, and were also unwelcome and even slighted by their comrades in arms. Kolesar was not particularly straightforward about this. The reason, it seems, was her good-natured personality. Neither the theater colleague who “forgot” to return her trousers, nor the anonymous person who stole her shoes while she was sleeping (shoes were a valuable asset among the partisans, as many soldiers spent long periods of time in soft peasant footwear or barefoot), or even the fact that military units as a rule considered that actors were a burden and treated them accordingly, failed to affect her kind disposition toward everyone she mentioned in her texts and interviews.

Yet there are one or two interesting, negative observations in her small written legacy. These concern the partisan cultural evenings that usually consisted of theatrical performances organized for the civilian populations followed by informal socializing accompanied by music, singing, and dancing. These were well-attended events at which young village girls wore their best dresses. There were, however, always fewer men (usually only the members of the visiting theatrical group) than girls, and so there was a scramble for suitable dance partners. Because of this, Kolesar writes, female members of theater groups had to approach the guests and ask them to dance. She adds: “As uninteresting as that was to me, I know it was the same for those girls!” It comes as no surprise then, that if a partisan took a liking to a comrade – as was the case with Irena Kolesar and Šime Šimatović who eyed each other until he proposed to her in the summer of 1944 – he or she might find such arrangements tiresome. Moreover, the mention of the small numbers of the opposite sex at some of the partisan cultural evenings is an obvious allusion to girls’ desire to indulge in heterosexual socializing. In other words, the partisan cultural evenings, alongside the official emphasis on political and cultural education, were used by young people as opportunities to meet, mingle, and have fun, as in peacetime.

Illustration:

Vladimir Balašćak (ed.), Osmeh porculanske figurine (The Smile of a Porcelain Figurine) (Sremska Mitrovica: Društvo Rusina i Novinarska asocijacija Rusina, 2020), 14.

Literature:

Irena Kolesar, “Moji doživljaji, moja sjećanja” (“My Experiences, My Memories”), Dani Hvarskoga kazališta: Građa i rasprave o hrvatskoj književnosti i kazalištu 10, no. 1 (1983): 269-286.

Đuro Zagorac, “Još uvijek je zovu Slavica” (“They Still Call Her Slavica”), Start 80 (February 9, 1972): 26-28.

Marriage

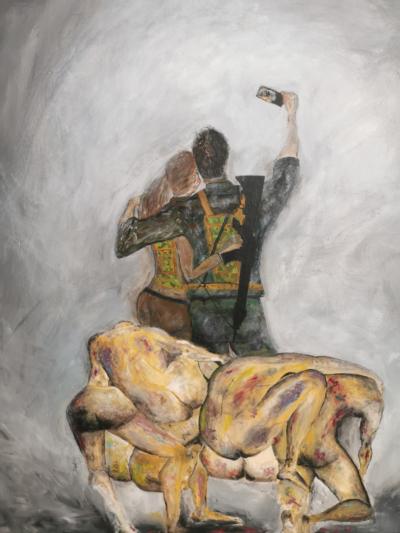

Soldiers deployed for war train and prepare for all kinds of danger and even death – but sometimes they find love.

This painting is inspired by the story of an American soldier who unexpectedly found love while serving on a small outpost in the remote mountains of eastern Afghanistan. Here she became friend with an Afghan interpreter who was always kind and helpful to all those around him. She admired this about him.

After her tour ended, the two remained friends and stayed in close contact. Overtime, the friendship grew into something more and two years later, the once US soldier returned to the tiny outpost in Afghanistan, but this time as a civilian to get married. The two married in a simple wedding and honeymooned in the capital Kabul.

This story touched me as it shows that love can be found even in the toughest and darkest of places. It shows that amidst the chaos, carnage and horror of war, we as humans still have the desire for friendship and love. In my painting, you see this couple on their wedding day with the groom in traditional clothes, but the bride in her military uniform, a reminder of how war brought them together.

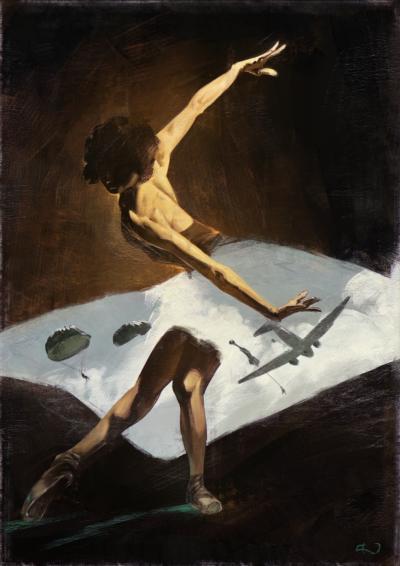

Mira, the ballet dancer

When World War II broke out, ballerina Mira Sanjina was part of the Croatian National Theater (Hrvatsko narodno kazalište) ensemble in Zagreb. After the establishment of the Ustasha-led Independent State of Croatia (Nezavisna Država Hrvatska), Sanjina (who was of Jewish descent) and her husband Ljubiša Jovanović (who was a Serb) fled from Zagreb to Split and then to Ljubljana. Finally, in 1943, they joined the partisans and the Theater of the People’s Liberation (Kazalište narodnog oslobođenja, KNO) in the liberated territory of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Recalling her first performance as a member of the KNO, the ballet choreography she performed to Dvořák’s Sixth Slavonic Dance played by pianist Andrija Preger, Sanjina described the intense feeling of pleasure: “I danced cheerfully, enjoyed the dance, surrendered to it; I danced in a very beautiful, white, fluttering costume made of parachute silk.” Her dance and her costume, however, caused embarrassment for the audience. That is, the differences in the understanding of appropriate female appearance and behavior made it impossible for Mira Sanjina to share the pleasure of ballet dancing with the Bosnian audience. For many attending the event, Sanjina was probably the first ballerina they had ever seen:

I was not aware of the extent to which it was a shock for an unaccustomed audience, the partisan fighters who lived under very harsh conditions, the Muslim women who had never seen a ballet. The appearance of a ballerina was something quite unexpected for them. […] The Muslim women felt shame while I was enjoying the dance. While I was getting carried away and dancing it up, they were ashamed. It seemed to me that they were exiting the hall bit by bit.

For her later wartime performances, Sanjina adjusted both her dance and her appearance. For instance, for the anniversary of the October Revolution observed later in 1943, she chose to play the “more suitable” Joan of Arc. In addition, the military superiors controlled her costume. On that occasion, Sanjina wore a dark gray woolen leotard. Moreover, until the end of the war, she for the most part danced in classical ballet performances, which usually contained folklore elements.

Informed by traditions and religion, local beliefs about appropriate femininity limited Mira Sanjina’s ability to perform expressively. However, although her classical ballet performances were customized with elements of folklore and although her revealing ballet dresses were replaced with more modest costumes, the wartime spectators, she maintains, responded to the adjustments with immense enthusiasm:

Even today I think that it was perhaps my most beautiful audience […] standing for a long, long time, breathless, […] watching and immersing itself [in the performances] with such curiosity and such attention. I think that I never have had such a nice experience and such wonderful contacts [with audiences] during and after my performances, certainly not in such a way. In the way of a wonderful, chaste audience that was so infinitely grateful, so curious, [the audience] that watched me dance with such pleasure.

Author of the illustration: Dario Jelušić

Sources:

Milohnić, Aldo. Gledališče upora (Theater of Resistance). Ljubljana: Akademija za gledališče, radio, film in televizijo Univerze v Ljubljani, 2021.