Born in the USA

When Philippe Bourgois shows affluent Americans photos from the inner city neighborhoods of large American cities, they find it hard to believe that what they see is the U.S. Run down factories and shattered buildings, mile after mile of abandonment. The photos evoke images of bombed European cities during the Second World War. Indeed, Bourgois calls on historical precedents like the Marshall Plan to explain the current need for state intervention in US inner cities.

- Segregation is not a strong enough word to describe the demography of many large American cities. We now use the term "hypersegregation." I have to use photos to illustrate. No words are powerful enough, says Philippe Bourgois.

In a city like Philadelphia, the demographic patterns are stark. Puerto Ricans and blacks live in the inner city areas, Whites live in the suburbs of the city and rarely go to the inner city at all. They live in separate areas and lead separate lives.

The problems started in the 1950s, when many factories were shut down and people lost their jobs. The population has been decreasing every year since 1951. There is no obvious reason why Philadelphia should be a wasteland. The city is located in a corridor of financial and political power and has access to the sea. Yet, the city is poor and cannot afford to clean up its waste. The problem of run down inner cities and poor neighbourhoods is a structural one, says Bourgois. It stems from an uneven distribution of resources and social inequality based on class and racialized ethnicity.

- In the U.S. there are huge differences in the distribution of resources and public services. Non-White areas have bad schools, brutal police and inferior investments. This creates a snowball-effect, says Bourgois.

The state used to spend large resources on housing and education. Now investments in life support schemes have been cut down, and more money goes to the police, to prisons and high tech medical care. The effect is that poverty is criminalized and pathologized. Bourgois pinpoints the poor quality of schools as one of the biggest challenges. Poor education leaves youths with little hopes for the future, and robs them of cultural capital.

- The problems are right there, but they are invisible to many Americans, he says.

Streets of Philadelphia

Philadelphia had the highest murder rate in the country last year. In addition to the segregation between blacks and whites, Philadelphia also has a large Puerto Rican community. The Puerto Ricans literally live in-between the blacks and the whites, not only demographically speaking. They are a true rainbow community phenotypically and have been for centuries. This gives them an advantage, unfortunately, when it comes to drug dealing, now the only equal opportunity industry employing many Puerto Ricans in Philly. They can mingle with blacks as well as whites, without the risk of standing out and without generating as much antagonism. This means that there is less risk of being spotted by the police, less risk of being suspected for drug dealing, and less random racialized violence.

Philippe Bourgois has conducted field-work in the Puerto Rican community in Philadelphia since 2007. He has followed many of the Puerto Ricans families living there closely for years. Many of them are drug sellers. Some of them have become his friends.

Initially, he found it hard to grasp how Philadelphia could be one of the most violent places in the country, because – like he says; the people there are so warm and friendly and welcoming--especially in the Puerto Rican community.

Many of the youth, however, will inevitably end up in prison because of the de facto criminalization of poverty. One of the main predictors of going to prison is having a family member that has been incarcerated.

-This has become a tragic state policy, essentially condemning children for the neighborhood and family into which they are born, says Bourgois.

He has seen the carceralization process take place with his own eyes. Many of the Puerto Ricans he has met during his fieldwork expect to go to prison. This expectation, paired with desperation, makes the prospects of drug dealing seductive.

-If you were a poor teenager with ripped sneakers living on a drug selling block and knew that you could make a hundred dollars in the next few hours, wouldn’t you take the risk as well? It is almost lack of entrepreneurship to not sell drugs when you are born in this vulnerable neighborhood, he says.

They live in an area where there are almost no regular jobs, no shops, no supermarkets--none of the infrastructure taken for granted in middle class neighborhoods. They are excluded from the opportunities that children and youths have in the more affluent areas of Philadelphia. He knows too many young boys and girls who are willing to take the risk.

-That is the most depressing part of this fieldwork; to witness this waste of human creativity.

Murder incorporated

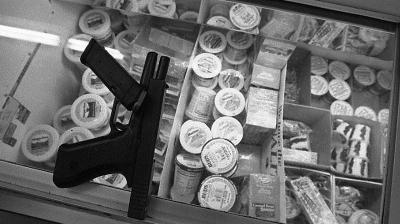

- The biggest problem in the US is the easy access to weapons, states Philippe Bourgois. He is not only talking about pistols, but semi-automatic and automatic firearms like AK 47s--even bazookas! Some even take pride in showing that they are experts on weapons, that they can recognize the sound of fire arms from a distance. Weapons have not only become standard equipment, but an esthetic fetish--a cool teenage fashion statement.

For many Americans living in the shattered inner city areas, weapons are seen as a practical necessity. The high level drug dealers all have access to weapons, but they do not carry them on a daily basis. They are stopped by the police too often to take that risk. Instead they keep their weapons at home or on their girlfriends. If they are threatened or insulted in any way, they bring out their guns to show them off. Sometimes, being known to have a weapon is enough to scare off troublemakers and enemies. Yet, far too often disputes end in tragedy.

- Even disputes over soap opera-style love affairs regularly end with automatic gunfire, says Bourgois.

Violence has become normalized in these areas, not only because of the easy access to weapons and the high level of social insecurity, but also because violence has become strongly linked to masculinity and self-respect. The unemployment rates are staggering. Men are not able to provide for their families.

- Being violent is the only space left in which they can excel. Violence becomes a skill. Fathers train sons. This is how they make their mothers proud and defend their family’s honour, he says.

This hard land

Trips to prison to visit fathers, sons or other close relatives have become part of everyday life for a rapidly increasing number of U.S. citizens. In the 80’s, the number of people sentenced to prison started scaling up. Now the country has the highest incarceration rate in the world. What has happened to the Land of the Free?

In the 70’s, people left the rural areas to head for a more prosperous life in the cities. The state’s response was to transfer resources to the white countryside in an attempt to stop the migration. One of the measures was to create more jobs in the countryside. Building prisons made jobs easily available, jobs for white countryside dwellers with little or no education. Now, the re-allocation of resources has evolved into a structural problem that according to Bourgois, is tragic, yet interesting from a sociological perspective.

-There has been a massive state transfer of resources. The irony is that poor whites have received subsidies at the expense of young urban black and Latino men.

Is it really that bad? Could Bourgois be accused of being a left-wing academic that has made up his mind to become a knight in bright and shining armour for troublemakers? The statistics support Bourgois’ grim picture of the situation. More and more Americans are incarcerated, often for minor criminal offenses.

-Offenders that would get six months or perhaps be enrolled in rehabilitation programmes in Europe, are routinely sentenced to 2-4 years in the US. The inclination to give lengthy sentences for even minor criminal offenses is perhaps the single most important factor that has filled our prisons to the rim, says Bourgois.

The media and politicians benefit from exaggerating the level of insecurity in the U.S. Crime sells newspapers. Politicians actively promise to clamp down on crime to buy votes. And people are seduced. The number of police officers has risen dramatically. Yet, security comes at a cost. It is expensive to keep that many police officers and prisons going. The prison wards are well paid. The Prisons Union has gained political momentum and has become a "Political Action Committee." In California, their union was the second largest contributor to political campaigns after the Doctor’s Union.

Interview by Åse Johanne Roti Dahl

Philippe Bourgois

Philippe Bourgois is Richard Perry professor of Anthropology and Family and Community Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. He is internationally renowned for his ethnographic research and long-term fieldwork. He spent five years among drug dealers in New York's East Harlem and more than a decade of fieldwork among a group of heroin and crack users in San Francisco. Bourgois has also done extensive fieldwork among Puerto Ricans living in the inner-city in Philadelphia. His research addresses inner-city social suffering, and raises critique of the political economy in the U.S. He has also worked in Central America, where his research has focused on the political mobilization of ethnicity, immigration and labour relations, political violence, popular resistance and the social dislocation of street children.