“That time and society has come”

The Sudanese religious thinker and leader Al-Ustadh Mahmoud Mohamed Taha was a passionate advocate for gender equality. In 1945, he founded the Republican Party which later developed to become the Islamic reform movement known as the Sudanese Republican Brothers. Women played an important role in the organisation from the start, and contributed in all activities under the name the Sudanese Republican Sisters

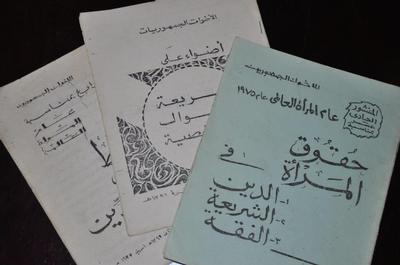

In 1975, the Sudanese Republican Movement celebrated the International Women’s Year by publishing 16 booklets about women’s rights. The booklets were distributed all over the country. In these booklets, issues like divorce, the personal status law for Muslims, and women’s rights in the Sudanese Constitution and in Shari’a were discussed.

The Sudanese Republican Movement argued that the basis for gender equality could be found in the Qur’an itself. “Sudanese women should claim the equal rights that are guaranteed in the 1973 Constitution and supported by religion. The personal status laws are exploitive and demand the domination and control of men over women. These laws are in fact unconstitutional because they consider men as protectors and maintainers of women, and because they differentiate between women and men in their rights. In Shari’a courts in Sudan, a woman is considered half a man in testimony and in inheritance (...) Moreover, a man has the supreme right to divorce by unilateral repudiation, reject a wife’s petition for divorce and forcefully subject the wife to the ‘house of obedience’. The question we ask is: How can the Constitution be valid while these discriminatory laws are implemented in Shari’a courts?”, wrote the Republican Sisters.

When the Nimeiri regime introduced new Shari’a laws in 1983, Taha refused to recognise the laws as Islamic. He termed them the September laws to dissociate Shari’a from the new law which he regarded as a misrepresented and distorted version of Islam. Taha’s radical interpretation of Islam is based on the Qur’anic distinction between the first and second message of Islam, differentiating between the verses revealed to Prophet Muhammad in Mecca and those revealed after his flight to Medina. He stressed that the message revealed in Medina was inferior to the message revealed in Mecca. In demonstrating the historicity of the Medina verses and its limitations, Taha focused on women’s rights. The verses of the Qur’an which describe women’s position of subservience to their fathers, brothers and husbands, count women’s testimony as half of men’s, and limit women’s inheritance are all in the verses revealed to the Prophet in Medina. Taha viewed the Nisa (women) chapter of the Qur’an, which contains many of the restrictions imposed on women in Islamic society, as belonging to historical or early Islam, that is, the Medina verses. Nimeiri’s September laws were based on the Medina verses, according to Taha.

The Sharia laws that the regime ruled by during the 1980’s were meant for a different kind of society, the kind of society that Prophet Mohamed lived in and had to relate to during the seventh century. The Sudan of the 1980’s was a wholly different matter. Taha argued for reviving the Meccan Qur’an as the basis for contemporary Islamic law, because these verses granted women and men equal rights. In one of his publications from 1976, he stated that “The Second Message of Islam lifts women to an equal status with men in all fields”.

Taha, sometimes referred to as Sudan’s Gandhi, was too radical for his time. In 1985, he was sentenced to death for apostacy and exectued. Are his thoughts still too radical for the Islamist regime in Sudan?

The Sudanese Republican Movement took a hard hit after its leader was executed. Most of its members were forced to live in exile. After the peace agreement in 2005, the Al-Ustadh Mahmoud Mohamed Taha Cultural Centre was established in Omdurman. Its members tried to register as a political party in 2014, but were not allowed to.

In the 1970’s, mainstream women’s rights activism in Sudan focused solely on women’s rights in the public sphere. Family law was out of bounds. The Sudanese Republican Movement was the only organisation that promoted women’s equal rights in areas like divorce and marriage. Their argumentation was very progressive at the time.

The personal status law for Muslims remains a battlefield in Sudan, and has been especially contested after the Islamist regime made a new law in 1991 which took women’s rights a step backwards.

-The Sudanese Republican Movement were advocating a very progressive interpretation of Islam on the issue of women’s rights. They highlighted equality and justice, and their arguments are very similar to the arguments voiced by Islamic feminists today. The Sudanese Republican Movement refused to accept traditional interpretations of Islam, arguing that society needed to relate Islam to the real lives and struggles of Sudanese women. It is unfortunate that they were silenced for so long, says Samia Al-Nager, lead researcher in a cooperation between CMI and Ahfad University for Women.

Today, the Sudanese Republican Movement mainly attracts young women and men who want to change women’s position in Sudan. Their heritage is now being revived. Through the CMI-Ahfad cooperation, the booklets they published during the 1970’s have been translated from Arabic to English in order to contribute to the ongoing debate on women’s rights in Islam in the Middle East and Northern Africa.