«Nowadays there are shoot-outs all the time». Women, children, and Police Pacification Units (UPPs) in Rocinha, Rio de Janeiro.

How to cite this publication:

Iselin Åsedotter Strønen (2016). «Nowadays there are shoot-outs all the time». Women, children, and Police Pacification Units (UPPs) in Rocinha, Rio de Janeiro.. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI Working Paper WP 2016:7)

Executive summary

This CMI Working paper explores the implementation of the Brazilian government’s favela (shantytown) policing program, Unidades de Pacificacion Policiais (UPP) or The Pacifying Police Units, from the point of view of women in Rocinha, Rio de Janeiro. It also offers ethnographic insights into how the presence of the UPP affects children.

The paper’s main contention is that the incursion of the UPPs in Rocinha since 2011 has produced a volatile and unpredictable violent dynamic between drug gangs and the police. People, including children, experience having their everyday life disrupted by the risk of being caught in cross fire between drug gangs and the police. Moreover, historically rooted high levels of mistrust towards the police remain, in spite of the attempts to re-brand the UPPs as a new form of inclusive community policing; many people would prefer that the drug gangs took control over the favela again rather than the police. These findings indicate that UPP in Rocinha have not succeeded in instilling an enhanced perception of citizen security, or in fomenting bonds of trust and cooperation.

These findings are discussed in light of the historical asymmetry in the distribution of rights and duties amongst Brazilian citizens, as well as the structural discrimination and marginalization of people from the favelas. Concurrently, it is argued that by addressing these aspects in depth a substantial and humanist security paradigm can emerge.

“The UPPs represent the consolidation of the pact between the Military Police and the citizens, to whom we must destine the best of our efforts. Besides hope and citizenship, UPP symbolizes all the appreciation we have for human life.”

Official web page for Rio’s Police Pacification Units (UPP)1

“When it was only the bandidos here, people respected the laws out of fear. There weren’t thieves or rapists, everyone followed the laws that they imposed. Now, it is worse. No one believes in the police or in the laws of Brazil. “

Girl aged 19, citizen of Rocinha

This CMI Working paper is a publication from the project Everyday Maneuvers: Military-Civilian Relations in Latin America and the Middle East. The project explores the historical, cultural and political ties between military actors and civilians, and is financed by the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Project leader: Nefissa Naguib

Project coordinator and editor: Iselin Åsedotter Strønen

Preface

It is barely ten thirty in the morning when the first fireworks explode outside, just a stone’s throw down the hill. Then all of a sudden, a lot of fireworks go off simultaneously; loud explosions echo through the broad and densely populated valley. I stand up and look out through the open window. Thin, white smoke is floating over the undistinguishable mass of shantytown houses. The children do not seem to notice much. This is a normal part of their world. Although not yet having reached the age of five, these children are all too used to the build-up of a shoot-out. Eleven of them are present this morning in Dona Sofia’s3 kindergarten, set in her own living room, and we have just washed up after having spent the morning playing with Lego. Dona Sofia, the only “employee” when she does not have volunteers to help her out, seems a bit nervous. The fireworks are heavier than usual.

Her unease stems from the fact that in the favela (informal settlement) of Rocinha, Rio de Janeiro, fireworks do not normally mean a celebration of any sorts. Rather, it means that the local drug traffickers are communicating the whereabouts of the police with one another. Up until 2011, when police troops entered and settled in Rocinha as part of the government’s high-profile security reform, the drug traffickers controlled the whole community. However, they still control the drug trade and exercise partial territorial control, but now in a highly fragile and volatile co-existence with the UPPs (Unidades de Pacificacion Policiais), as the favela on-site police units are called.

It is the youngest boys in the drug trafficking hierarchy, located at strategic points in the main streets and inside the favela, who send up fireworks if the police start to move into the areas where the traffickers are located. Little fireworks mean little risk—i.e., just a small police patrol doing a normal round. Big fireworks mean high risk—i.e., that the police are moving in man-strong in order to carry out an “operation”. Then, one of two things happens: Either the traffickers run off and hide deeper up and deeper into the favela; or they confront the police in a tiroteo-shoot-out.

Dona Sofia confers with her teenage nephew, who is in the house, whether they had heard just fireworks or shots as well. He believes that it was just fireworks, whilst she thinks that she had heard shots too. A few weeks before there had been a major confrontation between traffickers and the police in the whole area all morning, from eight until eleven o’clock. Unfortunately, one of the showdowns had taken place in front of the nearby home of one of the children in the kindergarten, Claudio. Luckily, he was in the kindergarten, and his elder brother and single mother were also not at home. But their home was badly damaged. Dona Sofia showed me some photos; the refrigerator was riddled with bullet holes. Claudio and his family had to move to a relative’s house close by, but Claudio was very unhappy. He didn’t sleep well or eat well. His mother was scared of moving back, didn’t have funds to remodel the house, and didn’t know what to do.

Before the UPP was installed in Rocinha in 2011 this area of the favela was much calmer, Dona Sofia had told me earlier that morning. The traffickers had mainly been present further down in the community back then, closer to the main street. But as the police took over “downtown”, the traffickers re-located further up the valley. However, before the “fireworks alert system” was invented it was a lot worse, Dona Sofia confided. As traffickers and police inadvertently ran into each other, shoot-outs erupted with even more frequency than today, and innocent people were often trapped in the cross fire.

The fizzling bang of fireworks fills the air again, this time closer. I am holding the youngest girl, eight-month-old Jasmine, in my arms. She has a bad cold, has been fragile and on the verge of tears all morning, and starts to cry with the loud bang. Nine-year-old Cristiano, another nephew of Dona Sofia, comes in the front door. He says that he has seen police troops moving up the narrow favela alleyways. Dona Sofia looks out the window and then around once more, clearly uneasy, before we continue the morning’s routine. The children are given rice and a vegetable purée, sitting on the six-square-meter floor available in Dona Sofia’s living room, before it is time for face-washing and a cup of water to drink. Dona Sofia is strict, but fair, as the children find their places in the line. When you are normally the only adult present in the kindergarten, taking care of up to 16 children on your own, you cannot give much leeway before tears, fights and quarrels break loose.

Just before noon, when I normally finish my morning stint as a volunteer, another round of heavy fireworks explodes nearby. I am supposed to descend through the favela and down to the main street together with Dona Sofia’s eight-year-old son, Tomas, who attends afternoon school, but she says that she will find someone to watch over the kids and follow us down. However, it is quiet, and eventually she says that we can walk alone as we normally do. The silence indicates that the traffickers have retreated far up the favela hill, and that the police are not following. Nothing more will come of it today. I wish Dona Sofia and the kids goodbye, and, together with Tomas, I walk down the winding, dirty alleyways and stairways through the favela. The narrow passages are filled with children coming home from morning school. This afternoon, at least, the inhabitants of Rocinha can continue their everyday routines without being interrupted by an all too common shoot-out.

The author wants to thank Nefissa Naguib and Celina Sørbøe for suggestions and comments to the first version of this paper. Any mistakes and shortcomings are entirely the author’s own.

Introduction

This CMI Working paper is concerned with understanding the implementation of the Brazilian government favela policing program, Unidades de Pacificacion Policiais (UPP) or the Pacifying Police Units, as experienced by women and children in the favela of Rocinha, Rio de Janeiro4.

Starting in 2008, 38 UPP stations have been installed across the state of Rio de Janeiro,5 with the stated aim of eliminating or weakening the territorial control in the favelas exercised by Rio’s infamous drug gangs. The timing of the implementation of the UPPs coincided with the preparations for the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Olympic Games, and nearly all of the “occupied” favelas, as they are called, are located in proximity to the zones where the sports games are taking place.

Perhaps the most emblematic of all of Rio’s favelas is Rocinha, which is considered Brazil’s largest favela. Situated on a hilltop between two of Rio’ most fashionable neighborhoods, Rocinha has been a hub for the city’s cocaine trade since the 1990s, and the stronghold for one of the city’s three large drug cartels, Amigos do Amigos (Friends of Friends).

It was perceived of, therefore, as a big victory when Rocinha was taken over by elite security forces in 2011, and the UPP were installed in 2012. However, shortly thereafter, the drug traffickers started to return and continue the drug trade. Today, the community lives in a fragile and highly volatile situation whereby drug traffickers and police officers co-exist literally a stone’s throw apart. At the same time, there is a continuous underlying tension and mutual distrust between the police and the favela population. This tension has deep historical and structural roots in the various ways in which, for more than a century, the favelas have been subjected to discrimination, marginalization and violence vis-a-vis the Brazilian state and wider society, as well as numerous interventions to control and contain the favelas and their residents. Significantly, this adversary relationship has taken the form of violence and abuse at hands of the police, who, in addition to being notoriously corrupt, have a long history of a “shoot first, ask questions” style of intervention in the favelas.

Women are often absent from or put in the background of analyses of violence and its effects (Wilding, 2010). And so, one could add, are children. In this ethnographic study, I have consciously sought out women as my local interlocutors. Moreover, I conducted participant observation in a kindergarten in the midst of the favela with the hope of learning something about how UPPs affect children’s everyday lives. It is not necessarily the case that women and men provide “unique points of view”. Surely, many of the reflections made by women that appear in this paper, could also have been made by men. However, my aim is to provide a contrasting view to that of the top-down political goals and discourses surrounding the UPPs programs. Whether we like it or not, women and children for a number of reasons are particularly vulnerable in precarious and volatile living conditions. By paying focused attention to these often-overlooked experiences, we may gain deeper insight into the compound human dimensions of top-down security politics as it affects children and women as well as men.

The first part of the paper provides an overview of how the favelas in Rio de Janeiro emerged, how they became a hotbed for drug trafficking, and the political context within which the UPPs were implemented. The second part of the paper explores how the presence of the UPP affects women’s and children’s everyday lives in Rocinha. Some final reflections on the subject are offered in the last part of the paper.

A short history of Rocinha

“I am always afraid when they are not inside the house, here with me,” Maria said: “Nowadays tiroteos— shoot-outs—can happen anytime. It wasn’t like that before.” Maria has two daughters: shy, giggling 15-year-old Solaida, and attentive, witty 9-year-old Janice. Maria is a 34-year-old morena (light brown skin color), with a motherly and warm radiance, wearing a flowery dress and sandals.

In addition to her two girls, she has nine children in her care in the kindergarten she runs from her house. Like Dona Sofia, who runs the other kindergarten that we got to know in the introduction, Maria provides a much-needed service to working parents in a neighbourhood where public kindergartens are virtually absent. The youngest child in Maria’s care is six months old. Sometimes, the children stay overnight if the parents are working—several of them as maids in middle-and upperclass homes. Sometimes, the parents leave their children with Maria whilst they are out in the street partying.

Her house, where she lives with her children and husband, is located in a part of Rocinha, facing north, that is referred to as the 099—named after a now-closed shop located on the street corner. From their platabanda (an open top floor) they have a million-dollar view of the famous statue Christ the Redeemer, the lake and upper-middle class neighborhoods around Lago Rodrigo Freitas, a snip of Ipanema, Copacabana, and further away, the upscale municipality of Niterói. They see directly down onto the horse track, the upper-middle class neigbourhood of Gávea, and one of Brazil’s top universities, Pontifical Catholic University (PUC). Maria and her family may be part of Rio’s 1.4 million favela dwellers, but at least they have one of the best views in all of Rio, regardless of class, color, income or status.

According to local historiography, the name of Rocinha (“little farm”), can be traced back to the early twentieth century when local residents started growing vegetables that were sold at an open-air market in today’s Gávea (Mundoreal, 2015). Rocinha is today considered the largest favela in Brazil, though the exact population size is widely disputed. The official 2010 census put it at just below 70 000, whilst other (including local) estimates arrive at somewhere between 100 000 and well below 200 000 inhabitants (Ivins 2013:86). Rocinha occupies approximately 1.43 km2, stretching down the mountain valley on both sides next to the famous peaks “Os Dois Irmãos” (the two brothers). One side faces central Rio with the Lagoa Rodrigo Freitas, Gávea, Leblon and Ipanema, and the other side faces the up-scale neighbourhood of São Conrado, where some of Rio’s richest families live. Because of its visual poignancy and unusual location—shantytowns across the world tend to be hidden away on the least desirable lands—Rocinha is often cited as a powerful example of the paradoxical proximity between rich and poor in Rio.

The community started to expand in the 1950s with the increasing flow of immigrants from the Northeast and Minas Gerais (Ivins 2013:85). This population growth was intrinsically tied to development processes elsewhere in Rio as immigrants came looking for work in the booming construction and industrial sector in the rest of the city (Ivins 2013:85). Unable to find housing in the “official city”, the immigrants opted for squatting in the hillsides close to their workplaces. In 1993, Rocinha was officially recognized as a “bairro” (neighbourhood) (Ivins 2013:85) though it continues to be perceived of—and is, for all practical purposes—a favela.

During the 1990s, Rocinha became the main point of sale for cocaine in Rio. Strategically located close to the city center, it was easily accessible for the upper- and middle-classes who are the main buyers of drugs. Moreover, Rocinha became famous for throwing the most spectacular baile funk parties, which were also attended by middle- and upper-class youth (Mundoreal 2011). Since 2004, Rocinha has been controlled by the drug cartel Amigos do Amigos (Friends of Friends). This is one of the three drug cartels reigning in different parts of Rio, the other two being called Terceira Comando (Third Command) and Comando Vermelho (Red Command). The latter is today in control of parts of the upper part of Rocinha, having taken advantage of the blow to Amigos do Amigos’ territorial control following the incursion of the UPP (Mundoreal 2012, field interviews).

Rocinha was controlled by Amigos do Amigos’s top drug lord, the infamous “Nem”—or, as his real name is, Antonio Bonfim Lopes—until his arrest by special forces in 2011. Allegedly, Nem was quite appreciated in the community, not only because his predecessor was famous for his cruelty, but also because he was considered as reasonably “fair” and “socially conscientious” in his rule.6 Moreover, I was told by a local resident, he forbade the sale or use of anything other than marijuana and cocaine within the Rocinha’s borders, which saved the community from the—in relative terms—significantly more destructive and volatile effects of crack cocaine and other cheap “leftovers” drugs.

Starting in 2006/2007, Rocinha received significant attention from the government through the PAC-program (Aceleração do Crescimento, the Growth Acceleration Program), a national strategy intended to reach and maintain a 5-percent annual growth through infrastructure- and development investments (Simpson 2013). As part of this program, a major sports-stadium with a swimming pool has been built at the entrance to the favela, as well as a footbridge designed by the famous architect Niemeyer. The adjacent buildings facing the up-scale neighborhood of São Conrado were also painted as part of the program (ibid). There are a high number of national and international NGOs working in the community, as well as a rich variety of shops, restaurants, public offices, and even several bank offices. In spite of this, the community has severe deficiencies in terms of water, sewage and infrastructure, as well as a full range of housing problems and a lack of health facilities and educational opportunities. For example, when a new public kindergarten opened in Rocinha in 2014, 200 000 families applied for the 150 available spots (Hearst 2014). Because of sanitation problems, the community also suffers outbreaks of tuberculosis and dengue.

Rio and the favelas

The favelas of Brazil represent a powerful and near-mythical imagery both inside and outside the country. Their visual poignancy, combined with tropes of drug gangs, violence, samba schools and baile funk parties has been projected by famous movies, such as Bus 174 (2002), City of God (2002) and Tropa de Elite 1 and 2 (2007/2010). Even if these imageries are nothing more than stereotypes masking the diversity, complexities and real-life challenges that the everyday life in favelas represents, as well as the deep structural injustice underpinning their existence, they have contributed to bolstering Rio’s favelas as perhaps the best known imagery of shantytowns on a global scale.7

In Brazil, famous for its high tolerance of social inequalities (Rother 2012), there is a sharp distinction between the favelas and its residents, the favelados, and the “official city”. This distinction is often referred to as a divide between the favela and o asfalto (“the asphalt”). For the social sectors living on “the asphalt”, the favelas are largely a no-go zone, and favela residents are subject to extensive social, political and economic discrimination (Pearlman 2010).

The favelas in Rio started to emerge with the abolishment of slavery in 1888, when thousands of freed slaves set up provisional settlements close to the city center. They were followed by unpaid veterans from the Revolta dos Canudos rebellion (Xavier and Magalhães 2003:2), and slowly, the favelas started to grow as new flocks of people migrated from the countryside in search for work and a better life.

Throughout the twentieth century, the relationship between the favelas and the official state and city passed through different phases, yet the favelas were always, and are still, viewed as an anomaly to the official city and society. Pearlman, an undisputable academic authority on Rio’s favelas, writes:

Since the late 1800s, in the ongoing effort to rid the city of these “leprous sores”, laws have been passed, building codes established, eviction notices posted, civil and military police deployed, and fires set in the dark of the night. (Pearlman 2011: 26)

Whilst the attitude towards the favelas during the regime of Getulio Vargas (1930–1954) was characterized by a partly benevolent, though insufficient, support, the military regime’s (1964–1985) approach was that the favelas needed to be removed and relocated with force if necessary. When democracy was re-installed in 1985, it was acknowledged that the favelas had come to stay, and the official discourse and focus shifted towards—albeit with patchy and insufficient attempts—upgrading and integration.

Simultaneously, as the favelas became the stronghold for drug cartels from the 1980s onwards, an image of the favelas as sites of danger, criminality and deviance became consolidated. Middle-and upper-class society (though being a key market for drug purchase) perceived of the traffickers and the rest of the favela population as one of a kind; the great majority of hardworking, honest people living there became guilty by association.

The ascendance of the drug trade was not a local phenomenon. Rather, it was partly spurred by the US War on Drugs, which forced drug traffickers in Colombia, Peru and Bolivia to search for new smuggling routes and markets. Rio then became a key hub for further transport to Europe and the US; large quantities also remained in the country. The favelas, with their territorial opacity in central locations, as well as a long history of limited state oversight, poverty and unemployment, were ideal places for criminal gangs to emerge and administer the trade8. Leeds (1996) has argued that the state’s repressive attitude in combination with protective absence produced a void that the drug gangs could fill. This, in turn, created a negative spiral. As the drug cartels gained control over favelas, a war-like discourse and accompanying practices emerged in relation to the state’s attitude towards these areas and the inhabitants (Leite 2012). As has been poignantly describe in the famous movies Tropas de Elite I and II, security forces habitually entered the favelas in search of drug traffickers as if entering a war zone—with a license to kill—at the same time as extensive corruption and unholy alliances made state forces de facto accomplices and partners in the expanding drug economy.

As the state had practically retreated from the favelas9 except for the police raids, and drug traffickers had taken over local governance, an additional “competing power” emerged, namely militias formed partly by former and contemporary police officers. In the name of saving the favela population from the reign of traffickers, they installed a harsh control regime of their own. As has been described by Janice Pearlman (2010), turf wars between drug fractions and/or militias, combined with the violence and the extortion-regimes they wielded, made life in many of the favelas unbearable.

The violent stew

Pearlman cites a mix of ten ingredients that together made up the violent metaphoric feijoada (staple Brazilian bean-and meat stew) that developed in the favelas over time. These are:

(1) Stigmatized territories within the city that are excluded from state protection; (2) inequality levels among the highest in the world; (3) a high-priced illegal commodity with the alchemist’s allure of turning poverty into wealth; (4) well-organized, well-connected drug gangs and networks; (5) easy access to sophisticated weaponry; (6) an underpaid, understaffed , unaccountable police force; (7) a weak government indifferent to “the rule of law”; (8) independent militias and vigilante groups who can kill at will (9) a powerless population of over 3 million people in poverty; and (10) a sensationalist mass media empire fomenting fear to sell advertising and justify police brutality. (Pearlman 2010: 174)

As this list of ingredients indicates, the challenges associated with the favelas are not their citizens as such, but a host of historical and structural factors that have systematically put the favela population in a vulnerable—and in many ways powerless—position. Today, 22 percent of the population of Rio de Janeiro lives in favelas, comprising 1.4 million people (World Bank 2012). Considering that Brazil is still the most economically unequal country in the world, there are enormous differences between favela-and non-favela residents not only in income, but also on the full range of other indicators. For example, life expectancy in Rocinha is 67 years, whilst in the neighboring middle-class community of Gávea, it is 80 years (Moré 2011). Reflecting on the large difference in educational opportunities, the literacy rate in Rocinha is at 87 percent, whilst in Gávea it is 98 percent. A UN Human Development Report on Rio de Janeiro in 2001 found that Gávea had the city’s second highest HDI (Human Development Index) with a score of 0.89 (similar to North-European standards) on a scale of 0 to 1, while Rocinha had the fourth worst at 0.59 (Sørbøe 2013) placing it in the category of “low” human development. There is reason to believe that this score has improved during the past decade, but the differences are still enormous, and the example still serves to illustrate the enormous gaps in life quality and life opportunities that co-exist in Rio.

Figure 1. The BOPE badge and logo.10

A legacy of violence

It has traditionally been the military police (Polícia Militar) and its special police unit BOPE (Batalhão de Operações Policiais Especiais) that have been in charge of security operations in the favelas. Although the Brazilian security apparatus has always been hierarchical and violent vis-a-vis the poor, the era of military dictatorship in particular crafted the police into a highly oppressive and militaristic organization (Saborio, 2014; Sørbøe 2013:34–35).

Indeed, Brazil has been infamous for decades for its police brutality. In the 1990s, death squads, formed partly of “off-duty” police officers and paid by business owners, gained headlines worldwide for executing street children. This practice is reported to continue today (Independent, 200911). It is estimated that the police are responsible for 2000 deaths per years (Economist 2014), and increasing attention has been directed towards the racial aspect of these deaths. A recent report by Amnesty International concluded that out of the 1519 people killed at the hands of the police in the period between 2010 and 2013, 75 percent of the victims were black men aged between 15 and 2912. In official reports, these deaths are often listed as “killed while resisting arrest”. However, it has been documented that many of these have the characteristics of executions (Soares 2009). Nilson Bruna Filho, the only Afro-Brazilian head of a state public defender’s office, has commented that:

“There is a saying that ‘black meat is cheaper’. People don’t get shocked to see a dead black person, because the person in their minds can be linked to crime… And, in Brazil, if a person is linked to a crime, then he can be killed.”13

Because of the racial profiling of men killed at the hands of the police, social movements have claimed that there is a genocide going on against black people in Brazil (Kimari 201314).

The UPPs

The formation of the UPPs has been cast as an attempt to reform entrenched police cultures and to encourage new modes of citizen-police relations. In order to avoid the impression that they have been “tainted” by corrupt networks, the cadres recruited for the UPPs come straight out of police training and receive training in human rights. The program has also become cast as a model for community policing, though critics have pointed out that it lacks the characteristics conductive to community policing (Saborio 2013:132).

Although heavily publicized at home and abroad, the authorities cautioned against expecting too much from the UPP reform. Indeed, state public security secretary José Mariano Beltrame, the “father” of UPP15, has stated repeatedly that the goal was never to eradicate drug trafficking. Rather, the aim was to take away weapons of war off the street, re-conquer the favelas from the drug traffickers in order to “give back” public space to the favela population, and to pave the way for additional processes of social and economic integration with the broader city. For example, he has been quoted as saying that:

The police are not there to be repressive or create a militarized situation, but to create opportunities for other things to happen. The UPP is an opportunity to integrate the favela in the city. If you do not, you are not able to turn the page of violence. The security is one part; it is there. But citizens need more. (Coelho 2014)

From its inception, authorities assured the public that the UPPs would be accompanied by programs for local social and economic development (Saborio 2013:132). Initially called UPP Social, the objective was to “strengthen the territorial control and pacification of the areas with UPPs” (Bentsi-Enchill et al. 2015). These promises have, by and large, hitherto not materialized (Council on Foreign Relations 2014, Ashcroft 2014) causing disillusionment and cynicism (Bentsi-Enchill et. al. 2015; Jacobs 201516). Indeed, in order to disassociate the association between the policing part of the UPP reform and the promises of social investments that originally accompanied it, UPP Social has since been re-branded Rio+ Social Program (Bentsi-Enchill et.al 2015).

The UPPs and the Sports Games

The first Special Police Unit for Neighbourhood Pacification (UPP) was installed in the favela of Santa Marta in 2008. The UPP subsequently took control over 38 favelas or favela complexes17 in the state of Rio de Janeiro, comprising 9 543 UPP police officers18. In reference to the military showdowns involved, the arrival of an UPP is in popular discourse termed “an invasion”. It starts with the arrival of the Special Police Operation Squad (BOPE), supported by naval and air forces, before the UPPs are installed with permanent headquarters (Saborio 2013:131). Initially, the “invasions” were carried out as surprise attacks, leaving scores of deaths. Subsequently, the authorities started to announce the date of arrival in order to give the traffickers a chance to leave and thereby avoid shoot-outs (Council on Foreign Relations 2014, World Bank, 2012).

The success of the UPPs in terms of crime reduction is mixed19. Early studies found that the number of homicides was significantly reduced in favelas with UPPs, whilst other crimes, such as robbery, rape and domestic violence, increased (Averbuck 2012).20 Later, there were reports of increased shoot-outs, as turf wars between gangs and confrontations between the police and returning gangs, emerged21. During the past years, there has been an increase in deaths at the hands of the police (Amnesty International 2016). There have also been significant increases in homicide rates in nearby cities, indicating that the expelled traffickers have moved into other regions. The city of Niteroi, for example, experienced a 116 percent hike in homicide rates in 2013 (Rinaldi 2014). Human rights abuses associated with the UPPs have also surfaced, including rape and homicide (Vigna, 201522, AFP, 201423).

Both social activists, residents and academics have frequently viewed the UPPs with skepticism, viewing it as an effort to “clean up” the city ahead of the sports games more than as a public security reform designed to tackle the complexities of citizen security and social integration associated with the favelas (Marinho et.al 2014). Evidently, it did not reflect well on Brazil’s international image that large parts of the city were controlled by gun-wielding youths in flip-flops, as it were. The UPPs have with few exceptions only been installed in the southern region of Rio, close to the hotels and sports venues used for the 2014 World Cup and 2016 Olympic Games (Conectas Human Rights 2012, Council on Foreign Relations 2014)24. The installation of the UPPs coincided with forced evictions in many favelas, as part of the “urban upgrading” and construction work prior the World Cup25. Indeed, more than 67 000 evictions have taken place between 2009 and 2013 during the administration of the current major of Rio, Eduardo Paes (Chagas 2015). These events, in combination with outrage over the amount of money spent on the sports games, sparked widespread demonstrations (with violent police response) gaining attention worldwide in the months running up to the 2014 World Cup as well as the current run-up to the 2016 Olympic Games.

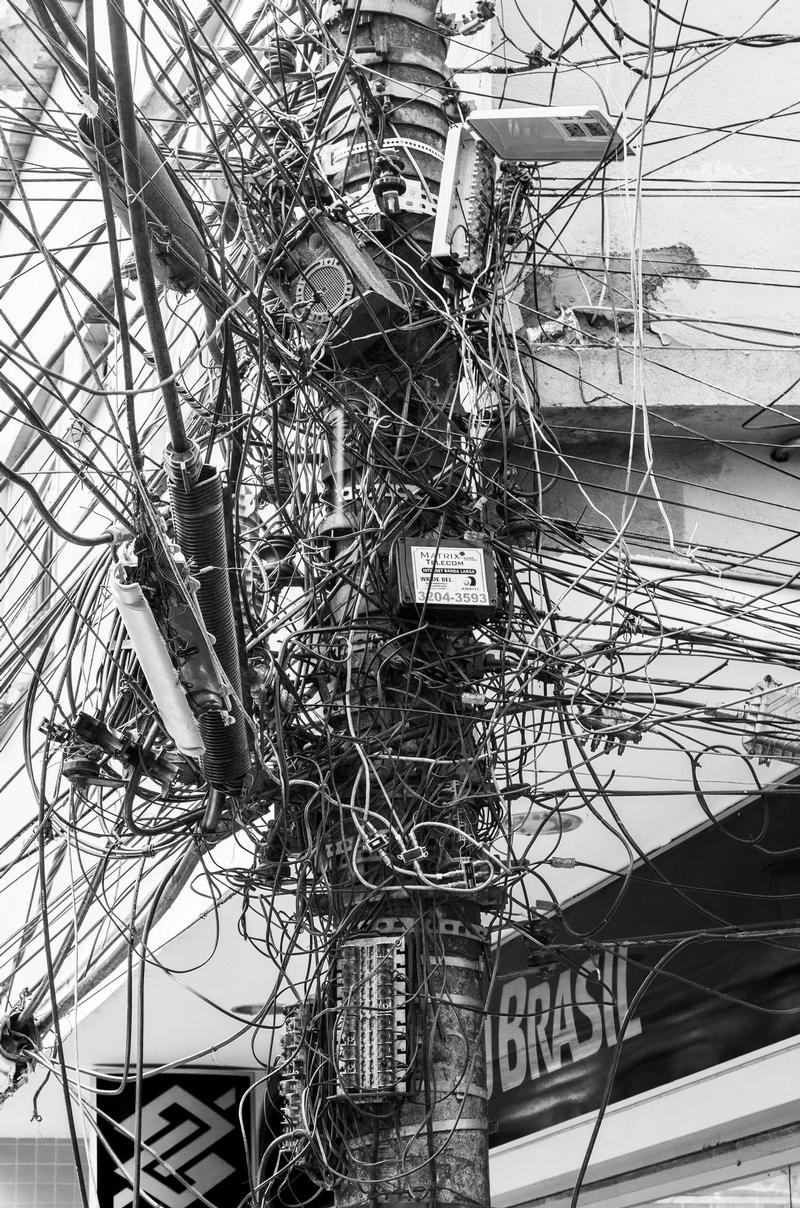

Another vein of criticism has focused on processes of accumulation-by-dispossession and market expansion that have taken place in the favelas by the combined effects of mega-event preparations, public-to-private transfers of state funds, and the state’s attempt to re-assert control over the favelas through the UPPs and other means. In many ways, this can be viewed as a neoliberal reordering and restructuring of the city, paving the wave for expanding market opportunities for private business and for capturing economic life in the favelas into market circuits (Savell, 2014; Saborio 2013; Sørbøe 2013)26. One aspect of this analysis is that the Brazilian boom during the past decades has converted parts of the favela population into lower middle-class, which has created a market for business that requires entering these neighborhoods. In practical terms, the extended realm of market actors and market regulations has had severe consequences for economic life in the favelas. For example, chain stores selling electro-domestic items have set up business inside the pacified favelas, forcing small, private shops out of the local market. Furthermore, commercial electricity, TV, and utility-companies have moved into the favelas, obliging residents to pay market-based fees for services that were previously obtained by informal means27. For favela residents living on low wages, these sums may be overwhelmingly high. Other consequences are the imposition of taxes on what were previously informal, small-scale businesses that may ruin their narrow profit margins. Moreover, real estate prices have gone up significantly in many centrally located favelas spurring a gentrification process,28 and many original residents have been forced to move elsewhere. Often, this is referred to by local residents as remoção branca (white removal). Rocinha, occupying perhaps one of the potentially most valuable lands in Rio, is an example of one of the favelas where this has taken place.

UPP in Rocinha

Rocinha was occupied by the military police BOPE in November 2011. In September 2012, the UPP unit in the community was officially inaugurated (Sørbøe 2013:6). In 2013, the UPP installed closed-circuit security cameras in the community, allegedly converting it into the most intensely monitored place in the world. Upon the initial invasion, Paulo Storani, a former captain in the elite squad BOPE leading the invasion, stated to Associated Press that

Rocinha is one of the most strategically important points for police to control in Rio de Janeiro…The pacification of Rocinha means that authorities have closed a security loop around the areas that will host most of the Olympic and World Cup activities.29

Prior to the announced invasion in 2012, the drug traffickers fled Rocinha and moved into other favelas. However, after a while, they started to return and the drug trade resumed (Mundoreal 2012); at the same time, as mentioned above, a rivalling faction moved in. This split-up of territorial sovereignty among different gangs, as we will see, is an additional factor for why life has become more insecure for ordinary citizens.

The UPP in Rocinha was thrown into a scandal in 2013, when the bricklayer and father-of-six Amarildo do Souza was kidnapped, tortured, murdered and disappeared at the hands of the UPP in Rocinha when he was out shopping for groceries.30 Following investigations, 25 UPP police officers were charged for participation in the crime, and the police commander was re-located from his post. Hitherto, the body has not been found, and the exact details of what actually happened to Amarildo are still unknown. This case, which also made international headlines, severely undermined the government’s attempt to brand the UPP as a new kind of police force without the violent sins of the past, and dealt a serious blow to citizens’ perception of the UPP.

Living in cross-fire in Rocinha

It was the last morning of my fieldwork in Rocinha, and, as usual, I tip-toed over the dirty alleyway crossing a small dirty water stream next to Dona Sofia’s house, before I knocked on her door. She opened with a gasp: “What are you doing here, haven’t you heard the tiroteos, the kindergarten is closed!” Then it dawned at me: the gut feeling that I had ignored as I walked through the streets from my home, had been correct. The streets were far emptier today than they were normally at 8 AM in the morning, and the fireworks that I had heard that morning were more frequent and louder than usual. And the sharp sounds that I heard just as I approached the final alleyway were gun fire, and the man who rushed past me as I did a slight, instinctive jump had said, “Stay calm, if not you only make it worse.”

Dona Sofia pushed me inside. More shots rang out down in the valley just in front of our living room window, and thin, white clouds of smoke dissolved slowly in the light morning air. Only three kids were sitting on the living room watching Peppa Pig-cartoons on TV, eyes fixed on the screen. None of them seemed to take notice of the gunshots. Their parents had brought them in very early in the morning, before the shooting erupted. The other parents were stuck at home with their kids, waiting it out. It was too high of a risk to take children out now.

The risk of getting caught in cross fire or take a bala perdida (lost bullet) was what everyone I spoke with feared the most. Shoot-outs also happened before the arrival of the UPP, but then with a different modus operandi, people stated. As one woman said: “The police entered Rocinha to do an operation at daybreak, did what they had to do, and then they left.“ Or there were limited periods when turf wars were going on, but then people knew about it and traffickers would warn people when something was about to happen. But now that the police were stationed in the community permanently, shooting could erupt everywhere and at any time.

The husband of Maria, who ran the kindergarten in her house as recounted above, told of an episode he had witnessed at the corner next to the entrance to their part of the favela. A police patrol had come down the street, seen a trafficker standing by the roadside, and started shooting at him with a fuzil (automatic machine gun), without taking into regard that the street was full of people. A woman had been hit in her foot and Maria’s husband thought that the foot had to be amputated afterwards. Another young girl told of a shoot-out outside her school when she arrived in the school bus with her mother. In that case, the tiroteo had calmed down after a while, she had gone to school, and her mother had returned back home. “But weren’t you shaken up?” I asked. “Of course I was,” she answered, but with a “what-could-I-do?” expression on her face. Yet another young woman told of how a tiroteo had erupted outside her home, she had fled the street and hid under her bed with her one-year-old daughter in her arms. “How did your daughter react,” I asked. “She was very nervous,” she answered, “she noticed that I was desperate.” The particular day when this event took place was a holiday (dia feriado), so there were a lot of people and, not least, children in the street.

It became clear from the interviews and conversations that the frequency of such episodes since the incursion of the UPP has left the population with a sense of living in a state of permanent potential exposure to risk. Mothers with older children, like Maria, expressed great fear that their children would get caught in cross fire in the street. One young girl was even explicitly forbidden by her single-parent father from being in the street at all, except when she was walking directly to and from school. In July 2015, a meeting was organized in Rocinha to discuss how the police could avoid carrying out operations when children were on their way to and from school and kindergarten. The mother of Wesley Barbosa, 13 years old, who was hit in the head by a stray bullet while in his own home, commented that

the operations are always taking place at the same hours. Six o’clock on the morning when everyone is on their way to school or to work, or noon or four o’clock, when everyone is leaving. (Vieira, 2015)

Dynamics like these, which put the population—and not least children—in the line of fire, are evidently not conducive to improving the relationship between the police and the community. Several women commented that the police exposed the general population to shoot-outs because they didn’t care about favela residents: “to them we are all bandidos,” one woman said—bandido is a common term used to refer to the traffickers. Many of them commented similarly; the police were not able to distinguish between criminals and honest, hardworking people.

Disdain from a distance

Corruption, next to violence, has always been the number one negative trait associated with the Brazilian police. As indicated above, the political ambition was that the UPPs would reduce this negative public perception of them. However, there were no indicators that people had faith that corruption had been reduced within the UPPs. As one woman put it: “The police are corrupt and they are cowards.” Several commented that “they are only here to get their money”. A few were careful to modify their statements by saying that not all police were the same and that were some you could trust, but overall, it was evident that the level of trust in the police was extremely low.

According to UPPs official website, UPP in Rocinha consists of 700 police officers. Most of the day, there is a small group of policemen (and a few women) who are to be found either in the shadow of the passarela (footbridge) by the entrance to the main street Via Ápia, or in Via Ápia itself. They are armed, some with machine guns, and wear bulletproof vests. Police cars also do rounds up and down the main streets. Sometimes the officer in the passenger seat has his machine gun stuck out of the open car window, producing a strong sense of intimidation as you find yourself with a machine gun casually pointed at you as you stand on the sidewalk.

Their lack of integration into the community is visible in the lack of contact and interaction between them and the passers-by; it is as if they are air to people and people are air to them. Sometimes, they go into restaurants to have lunch at a table of their own, or they look at the goods for sale at street vendors’ stalls. However, there is an air of isolation surrounding them, as if people radiate that they do not want to be involved, and as if they themselves know that they are not welcome31.

The apparent air of isolation surrounding the police has an extra dimension: one woman told me that the traffickers really do not like for people to chat to the police––a “trafficker” rule that is widespread in communities under their control (Wilding 2014). There have also been indicators that those residents who initially collaborated with the police were muted or even killed (Mundoreal 2012). A mother, who had caught her 12-year-old son talking to the police, became nervous of a knock on the door and an inquiry as to what her son was up to. This example indicates the entrenched difficulties of the mode of overlapping sovereignties that co-existence represents: the police and the traffickers are both fighting for control, and the population is best off not siding with either so as not to risk retribution from the other side. That makes it evidently very difficult to implement a community policing model.

That being said, very few of my interlocutors stated that they were afraid of the police as such. Moreover, very few had had negative personal experiences themselves with the police. One girl had experienced one or two cat calls, and a mother, who was fiercely critical of the police, recounted that the police once had drawn a gun and put it to her drunken son’s head after a quarrel in the street. “I cannot get that memory out of my head,” she said. Two young girls told me that they had been body-searched by a male police officer even though it is against the law, and one young girl had managed to avoid it through heavy protesting. However, the general attitude was “disdain from a distance”, and that it was best not to have anything to do with them.

Common and sexual crime

A recurrent theme in my field interviews was whether if being in the street (ficar na rua) is as dangerous for girls as for boys. About half of my field interlocutors said that it was the same; “gender-blind” shoot-outs was the safety issue most immediately present in people’s minds. The other half argued that it was more dangerous for girls, citing rape as the main cause for this perception, alongside the risk of getting robbed. Girls’ lesser ability to defend themselves was seen as a reason for why a girl was more likely to be robbed than a boy.

However, everyone I spoke to in the course of my fieldwork stated that common crime and rape had become a more frequent occurrence after the entrance of the UPPs. An increase in these modes of crime has been reported from other communities under UPPs control (see above); earlier statistics from Rocinha indicate the same although the numbers are difficult to interpret (Rousso 2012). I have not been able to obtain more recent statistics from Rocinha for this study. There have, however, been several cases covered in the press of rape within the confines of the community during the past years.

In order to understand how an increase in sexual and common crime can occur, we need to know how law and order was exercised previously. Under trafficker rule, they were the ones who “legislated” and enforced law and order in the community. In order to maintain territorial control, social support and a good business climate, criminal activities other than their own business was not allowed. Hence, rape, robbery and break-ins were virtually non-existent, as the perpetrator would be “taken care of” by traffickers, meaning everything from a warning, to expulsion, to death.32

As the UPP entered, this socio-territorial control was lost. Moreover, whereas the traffickers previously had controlled who entered the community by patrolling the entrances to the favela, it is now easier for non-residents to come and go, and to commit crime within the confines of Rocinha. Consequently, the social fabric and social control have become more opaque, and the police are seen as either unable or unwilling to step in and take people’s need for everyday security seriously. One girl said, pointing down the valley towards the main street: “The police are only down there. Up here, we are left to our own luck.”

However, the traffickers still exercise “law and order” in some ways, though a lot more territorially patchy and less total than before. One woman told me of how a string of people, (i.e., robbers) were “castigated”—that is, badly beaten up—in the alleyway behind her house only a few weeks before. When she opened the door in the morning the sand outside was covered with bloodstains33.

Many, if not most, of those interviewed expressed a preference for the continuation of trafficker’s vigilante system. On one occasion, when I asked a group of women what they thought would potentially improve the security situation in the community, one woman burst out quickly “that Nem [the now imprisoned former dono of Rocinha] comes back” and then they laughed amongst themselves, seemingly believing that the comment would pass over my head. Several people commented that “the traffickers one could talk to” (as opposed to the police) and that the traffickers respected ordinary workers. The presentation of this imagery of a completely peaceful co-existence between traffickers and ordinary people is evidently a truth with modifications, e.g., traffickers often “tax” businesses inside favela communities. As Wilding (2014) has argued, “trafficker rule” is a highly volatile and unpredictable affair, which is contingent upon the dono do morro (gang leader, literally “owner of the hill”) and each gang member’s will, mood, and disposition. The “acceptance” of trafficker rule may also be seen as a psychological defense mechanism in the face of a highly unpredictable and insecure state of living (ibid).

However, the fact that people perceive of it this way—most of them seem to remember the days of trafficker control with a sort of “nostalgia”—reveals that most people perceive of the traffickers as the lesser of two evils. That in itself is powerful evidence of the challenges facing a meaningful implementation of state security in the favela. One girl aged 19 summed it up very crudely:

When it was only the bandidos here, people respected the laws out of fear. There weren’t thieves or rapists, everyone followed the laws that they imposed. Now, it is worse. No one believes in the police or in the laws of Brazil.

The last part of that girl’s statement is highly revealing: the favela population still does not believe that the police are there to protect them or that the Brazilian justice system is made to, or capable of serving them as citizens. Unfortunately, the loss of traffickers’ rule meant the loss of the only system for justice and order that they could relate to, however tentatively and however volatile and potentially dangerous.

What happens if the UPP retires?

So far, there are no indications from the government that the UPPs will be phased out. Their founding father Beltrami has given reassurances that the UPPs are part of a long-term effort, but future electoral results may jeopardize this ambition. In that regard, it is worth having in mind that Rio has seen police reforms, including community policing, come and go before, only to end when new political powers take office.

However, there are many who suspect that the UPP will retire once the Olympic Games are over in 2016 (Council on Foreign Relations 2014). This view was also expressed by some of the community members whom I spoke to. As one girl said: “The UPPs will continue a bit more, just for appearances, and then it will be finished.” This statement must be seen in relationship with the above-mentioned perception of the UPPs as part of a clean-up effort ahead of the Olympics; a view shared by many favela residents. As another girl commented dryly: “The UPPs were about making the favelas more accessible for tourists to the sports games, so that they can come and see the views.”

Asked what they thought would happen if the UPPs were withdrawn from Rocinha, about half of the interlocutors answered flat out that they thought that the traffickers would take full control again, it would go back to the way it was before, and the security situation would get better. However, others were more cautious, and stated that it would be worse for a while whilst different commandos or fractions would be battling for control, and then it would be better again once the turf wars were over. One woman feared that it would be worse and completely out of control because of renewed wars between different commandos. The overwhelming majority, however, responded that it would become better, either immediately or after the turf war was over. Nevertheless, in spite of the prospects for an (temporary) upsurge of violence, all of the 22 women interviewed, except for one, preferred not to have the UPP present in the community.

Social and physical landscapes

Albeit far from exhaustive, this study does reveal that there are some perceptions that appear highly generalized: the security situation has gotten worse with the UPP34; people do not trust the police; and, people think that the traffickers will be in charge again—with or without turf war—if the UPP retires. Rocinha has been highlighted as one of the communities where the UPP has received the most resistance from traffickers (Rocha et.al. 2013), and where there has been the least success in terms of forging bonds with the community (Mundoreal 2012). This might not only be due to the case of Amarildo do Souza, but also to the fact that the sheer size of Rocinha makes it extremely difficult to control (Bottari and Vasconcellos 2013). There are indicators that the UPP have had more success in small communities (Mundoreal 2012); in some smaller pacified favelas, homicide rates were reduced to zero in 2013 (Hearst 2013)35

As frequently highlighted by ethnographers, any public policy targeted at the favelas must incorporate a keen understanding of the complexities of the favela’s quality as an intrinsically interwoven social and physical terrain. Constructed by thousands of narrow, crisscrossing non-linear alleyways, stairways and paths as well as tens of thousands of houses built asymmetrically under, on the top of, and next to each other, it is a highly challenging, if not impossible task for outsiders to maintain territorial control over the favelas. It is a dense ecosystem where social ties, community history and family relations are inscribed in the creation of and use of physical space, and that is the result of an almost unimaginable amount of human labor, sweat and sacrifice throughout decades.

The traffickers were able to wield control over this physical landscape not only by means of sheer force, but because they were intrinsically part of the social landscape—for better or worse. The police, on the other hand, lack an intimate knowledge of the inside of the favela, and this, in combination with the broader history of favela-police relations, constitutes the latter as an alien force in this panorama: as the executor of power that is not viewed as legitimate nor desired. Cramped and enclosed physical features also make the favelas a highly lethal trap if gunfire erupts, and the fact that police operations put innocent people’s lives at risk only confirms to the population that they are still considered disposable lives. This perception constitutes a continuation of a long history of the Brazilian state’s treatment of the favelas as a “site of exception”. As Janice Pearlman writes: “The lives of the poor have always been cheap, but in the milieu of drug and arms traffic, they have been devaluated even more” (2010:162).

“May God protect us all”

Some of those interviewed did express that it was an improvement that youngsters with guns no longer freely patrolled the streets. However, the great majority were careful to emphasize what they viewed as the negative consequences of the UPPs, reflecting that, at the end of the day, it is the lived experience of everyday security that matters for most people. The aforementioned “father” of the UPP, José Mariano Beltrame has indicated that the UPPs must be judged on their merits in the long run and as part of a broader transformation (Rocha et.al. 2013). However, as this paper has indicated, the UPPs have made favela residents’ lives more unpredictable and insecure, and that is what they care about the here and now. As young one woman said, “People from the outside say that we are better off now, but it is we that have to live with the consequences.” The perception of being trapped in a situation not of their choosing can be read in a series of Facebook-postings from the morning that I recounted above, when shooting erupted early in the morning. On a Facebook community page, I later read the moderator’s post:

Beware: shots and fireworks.

Shots and fireworks can be heard in the lower part of the community. Residents, please take care when you go out.

Throughout the morning, several residents commented on the post:

“God, how long are we going to live like this?”

“This has already become a routine, we want to have our right to come and go as we like.”

“Shots here in Rua 1 as well, we cannot sleep because we are afraid of a lost bullet…”

“A lot of shots…”

A woman with a profile photo of herself with a baby, had written: “It is here, in Rua 2.”

Another woman had written: “It is tense here in Vila Verde as well, may God protect us all.”

Yet another woman had written: “It is the time when children are going to school, and the police have to plan for an operation…”36

That morning, as we learned, “my” kindergarten was closed because of the danger of going out, and the streets were almost empty. As Dona Sofia hastily ran me back down to the main street “before it gets worse”, scores of police patrols had arrived and were roaming the streets, and a black helicopter was circling low over the community. It felt like a war scene. As a result, many people were not able to get to work that day, and many children did not go to school or kindergarten. Clearly, being locked up in your house in an extremely dense and opaque physical landscape echoing with gunfire produces a lot of stress, yet this is the everyday reality of the UPP in Rocinha. This dynamic not only makes winning people’s “hearts and minds” extremely problematic (with the paradoxical and tragic effect that people “long” for the reign of the traffickers), but also makes carving out a strategy for how to proceed very difficult if citizen security and renewed state-citizen and state-police relationships are the goal.

Final reflections: re-thinking security

There is a mother in Rocinha, let’s call her Sonia. Her life is a story first of tragedy, then salvation—literally—and now she is fighting to avoid another tragedy. Sonia used to live on the street, using drugs and alcohol. She has a son, William, who was taken away from her by her family because of her life style. He is now 11 years old. Then she had another son, Jesús, who is now three years old. When Jesús was born, she found the strength to recover from her addiction. Accompanied by family, she started to attend one of the many evangelical churches in Rocinha, where she was christened. She got back on her feet, was helped with finding an apartment, and eventually she got William back and settled down with her two sons as a working single mum. Jesús attends kindergarten; he is a restless boy, constantly wanting to be hugged, who has had to switch kindergarten two times already because he is perceived of as a “handful”. William is already attending school. But since Sonia is working long hours in a shop in Rocinha, she is paying someone to bring him from home to school in the morning and back home again in the afternoon. Sonia’s pending tragedy is this: William has already gotten a taste of hanging out in the street. When he has been left at home by the person who is paid to take him there, he more often than not goes out again. And Sonia knows very well what that might lead to. Indeed, everyone knows very well that those kids who “hang out in the street”, can easily by picked up by and seduced into joining the drug traffickers as “scouts” and delivery boys. Everyone knows that this is a high-road to an early death—traffickers rarely live beyond 30 years old. So, there she is, Sonia. Struggling to make ends meet in a very poorly paid job, single mother of two unruly boys, who in the evenings and nights often has to roam the streets of Rocinha to find her eldest son, before it ends in tragedy.

This is not at all an attempt to blame crime on poor mothering. Rather, it is an acknowledgement that mothers often bear the heaviest burden in trying to buffer the absence of social support and social protection. It is also an acknowledgement that the compound dynamics of social and material deficiencies characterizing favela life often function as a “channel” for steering young boys in particular along a criminal life path. In my interviews, I asked the women what they would do if they had the power to change three things in order to improve the security situation in Rocinha. What came up in more than half of the conversations was education, sports fields and social activities for youth. As an elderly mother of four, now grown boys said:

Make a lot of schools, high schools, volleyball courts, football fields, kindergartens…if you do all this, the security situation will be better, if the kids are occupied with good studies instead of being in the street and learn things that they ought not to learn—they need to have their minds occupied!

Both in Harlem (Bourgeois 1995), Caracas (Strønen 2014) and Rio, “street corner socialization” constitutes an arena where young men in particular are drawn into a volatile mix of alternative economic pathways and alternative social codes and values. Janice Pearlman (2010) writes poignantly about the “push” and “pull” factors that contribute to steering young boys into trafficking. One important issue to address is the gap between the end of mandatory school at the age of 15 and when recruits can join the military at the age of 18 (Pearlman 2010:207). These are highly critical years for young, unskilled favela boys, who, because of racism and prejudices, face substantial challenges in obtaining work. The traffickers provide identities, friendships and belonging (Pearlman 2019:307)—some of the most powerful of human needs. If you come from a poor background with a difficult family history and few other arenas where you receive positive feedback, this is one very easy “push” factor. A 20-year-old girl I spoke to, who was hoping to embark on studies to become a physiotherapist, put it this way:

If you are from a bad family structure, your school does not work, there are no teachers there when you come to class, there is no social work to help you, you are experiencing hunger, where are you supposed to go? The government will not help. So then someone comes and says, ‘Hey, I have also had a bad time, I also used to live in poverty,’ and then you get involved [in the traffic]. No one knows the life history of others.

A similar view has been put forward by the Brazilian anthropologist and criminologist Luiz Eduardo Soares:

We have to offer youth at a minimum what the drug trade offers: material resources, of course, but also recognition, a sense of belonging and of value…no one changes if he or she thinks that they are worth nothing. Do we want to exterminate poor youth or integrate them? Pardon and give a second chance also means forgiving ourselves and giving ourselves a second change, as a society. Wouldn’t it be great for us to have a chance to escape from the horrible guilt of having abandoned thousands of children to the fate of picking up a gun? (Soares quoted in Pearlman 2008:308)

Taking cues from these insights, we may conclude that “insecurity” in the context of Rio’s favelas needs to be approached as an intrinsic effect of socio-economic inequalities and social marginalization, in combination with a host of other factors within and beyond Rio’s and indeed Brazil’s borders. It is extremely difficult, if not impossible, to contain and control the proliferation of drug gangs and its ripple effects unless one starts by addressing how society “produces” those who fall outside the legitimate social order in the first place.

Conclusion

This CMI Working Paper has provided an overview of the main features and controversies associated with the implementation of the UPPs in Rio, at the same time as it has explored how insecurity is lived and perceived from the point of view of women in Rocinha. It has also provided ethnographic insight into how children are affected by everyday insecurity. Wilding (2010:722) has problematized how women’s perspectives on and experiences of the so-called “new urban violence” often tend to be ignored in research. She has also observed this pattern in much of the existing literature on gang-related violence, police abuse and paramilitary activity in Brazil (ibid). Although one could argue that many of the perspectives that have come out in this CMI Working Paper are “gender neutral” in the sense that they offer generalized perspectives on the UPPs and their effects on the community at large, it is evident that some of the issues explored here are clearly gendered.

Particularly, the heightened fear of rape is an issue that overwhelmingly concerns women. Likewise, as a great number of households in the favelas are female-headed, the interruption of everyday educational- and labor routines caused by episodes of shoot-outs affect women disproportionally and differently than men (Wilding 2010:740). Moreover, albeit not investigated in this study, there are reports that cases of domestic violence have increased in the aftermath of the installation of the UPPs. From other studies, we know that drug gangs have also functioned as arbitrators, judges and punishers in cases of domestic violence (Wilding 2010:73237) in the absence of police “interest” in these issues. A timely research question is, therefore, if women in UPP-communities now seek out the local police station in cases of domestic violence, or if the loss of “drug-gang justice” has actually left them more vulnerable.

Penglase (2014) has argued that the “innovative” aspect of the UPP is that it combines a unique approach to community policing and counter-insurgency. The question remains if this combination—similar to the violent husband who hits with one hand and caresses with the other—does not in many aspects constitute a contradiction. As this CMI Working paper has demonstrated, as have other publications on the issue, the UPPs inevitably throw up a host of paradoxes and catch-22’s. The most glaringly visible is this: the continuation of the drug economy and associated socio-administrative structures (drug gangs) in parallel with the presence of the police (who continue to feed off the drug economy) will continue to produce confrontational dynamics that inevitably puts the population at risk.

The continuation of a counter-insurgency model that leaves scores of drug traffickers dead clearly undermines the institutionalization of a universal “human rights” culture across Brazilian society. For example, when a most-wanted drug kingpin was recently killed in a police operation in Complejo de Maré in Rio, José Mariano Beltrame (the aforementioned “father” of UPP) stated in an interview with Brazilian press, “The Playboy is one more a dead bandit. We will not value these bandits. This was one and there will soon be another in his place. He will also get his turn” (Ferreira 2015). Such a statement implying that some lives are easily expandable is simply a continuation of the same discourse that has always differentiated and alienated the poor, non-white segment of the population. Moreover, though it was not UPP forces that shot “Playboy”, the continuation of “killed during resistance” murders reinforces the impression that the authorities and the gang members are still engaged in a lethal war. The efforts to advocate for a new citizen-police paradigm then becomes a thinly disguised version of para inglês ver (“for the Englishmen to see”)––that fine Brazilian expression that describes a law created “just for appearances”.

By reporting that people perceive of the security situation today as worse than before, and that many even want the traffickers to take control again, it is not my intent to justify or glorify the traffickers’ vigilante practices. Indeed, we need to abstain from glorifying them as defenders of “the little man” or some kind of Robin Hood. However, we also need to be careful about demonizing those who enter into the drug trade and thereby continue the processes of “othering” that underpin the broader scenario of social marginalization that favela populations—and young men in particular—are subject to. Rather, we should take great care in understanding which factors are “producing criminals”, and how these factors may be reversed. The evident point of departure for such an analysis is the historical asymmetry in the distribution of rights and duties amongst Brazilian citizens, as well as the structural discrimination and marginalization of people of color and lower class. Concurrently, it is through addressing these aspects in depth that a substantial and humanist security paradigm can emerge. Indeed, critical approaches to security studies have highlighted the need to approach the concept and condition of “security” as intrinsically interwoven with the broader human condition in terms of life choices, political emancipation and welfare (Booth 2007). Such a perspective has also contributed to shaping this paper, reflecting on the fact that women in Rocinha themselves address educational opportunities and social welfare as factors that could contribute to increased—and sustainable—security in the community.

As has been addressed in this paper and elsewhere, many favela residents are skeptical of the “real intentions” underpinning the implementation of the UPPs. We need to understand this skepticism not only in light of widespread critique of how preparations for the 2014 and 2016 mega-events have been used as leverage for a range of interventions in the favelas and (extremely expensive) urban restructuring, but also in light of how the favelas always have been an area of containment and control.

Furthermore, current skepticism must be viewed in light of in light of UPP history: they were intially presented as a “full” package including extensive social investment. In Brazil, as in other Latin American countries, citizens are highly accustomed to politicians’ lofty promises, white elephants and high-profile projects that fizzle out once the electoral period is over, media attention declines, or the money has dried up. As Pearlman has suggested (Council on Foreign Relations 2014), the positive perceptions initially surrounding the UPP presented a window of opportunity to prove that this time it was different; that this time the promises of social investments and community participation would really be true. However, as the situation is today, with the gleaning absence of substantial social transformation, this window is arguably lost. As the Rocinha-based community observatory Mundo Real (www.mundoreal.org) argues, UPP cannot work unless it is accompanied by sweeping socio-economic changes, as well as head-on confrontation with “the enemy within” (i.e., corruption within the police force) (Mundoreal 2012).

At the moment, the UPP budgets have been slashed as a consequence of the ongoing Brazilian economic crisis, seriously debilitating police operational capacity ahead of the August 2016 Olympic games. 38 Time will tell how long the UPP will remain in Rio’s favelas. However, the authorities backing the program have in many ways embarked on a path with very high exit costs. If the UPP retreats, a wave of turf wars and acts of retaliation will most likely follow, once again leaving the favela population to live with the consequences of political decisions made far beyond their control. As for the relationship between the security apparatus of the state and the favela population, it remains to be seen if the UPPs have constituted at least a minor step towards increased trust and approximation. In Rocinha, in order for this to happen, the major challenge is to break the dynamic of shoot-outs that make people perceive of the police as an cause of increased insecurity, rather than of peace.

Photo: flickr-user sandy marie, CC-licence

Bibliography

Amnesty International.2016. Rio 2016: Surge in killings by police sparks fear in favelas 100 days before Olympics. Press release on April 26, 2016. UK: Amnesty International, available at https://www.amnesty.org.uk/press-releases/rio-2016-surge-killings-police-sparks-fear-favelas-100-days-olympics. Last accessed July 4, 2016

Ashcroft, Patrick and Rachael Hilderbrand, 2015, Pacifying Police Unit (UPP) Installations Part 1: 2008–2010. www.rioonwatch.org, available at http://www.rioonwatch.org/?p=16065. Last accessed August 20, 2015

Ashcroft, Patrick. 2014. History of Rio de Janeiro’s Military Police Part 1: 19th Century Beginnings. www.rioonwatch.org, available at http://www.rioonwatch.org/?p=13506. Accessed on August 20, 2015

Averbuck, Julia. 2012. UPPs Reduce Violent Deaths by 78 percent. www.riotimesonline.com, available at http://riotimesonline.com/brazil-news/rio-politics/upps-reduce-violent-deaths-by-78-percent/, accessed August 20, 2015

Barber, Mariah.2016. Funding Shortage and Increased Violence Amounts to UPP Crisis. www.rioonwatch.org, available at http://www.rioonwatch.org/?p=28108. Accessed on July 4, 2016.

Bentsi-Enchill, Ed, Jessica Goodenough and Michel Berger.2015. The Death of UPP Social: Failing to Make Participation World. www.rioonwatch, available at http://www.rioonwatch.org/?p=17660, accessed August 21, 2015

Booth K (2007) Theory of World Security. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bottari, Elenilce and Fábio Vasconcellos. 2013. Topografia dificulta policiamento na Rocinha. www.oglobo.com, available at http://oglobo.globo.com/rio/topografia-dificulta-policiamento-na-rocinha-11044741, accessed August 20, 2015

Philippe Bourgois. 1995. In Search of Respect: Selling Crack in El Barrio. Cambridge University Press.

Carpes, Giuliander 2014. Desaparecidos e esquecidos, www.apublica.org, available at http://apublica.org/2014/02/desaparecidos-esquecidos/. Accessed August 20, 2015

Chagas, Maria. 2015. Book Maps Forced Eviction of Residents During Eduardo Paes Administration. www.rioonwatch.org, available at http://www.rioonwatch.org/?p=21863, accessed August 21, 2015

Coelho, Alexandra. 2014. José Mariano Beltrame: “As polívia deve deixar de ser militar, mass isso não acontece de um dia para o outro”. Available at http://www.publico.pt/mundo/noticia/a-policia-deve-deixar-de-ser-militar-mas-isso-nao-acontece-de-um-dia-para-o-outro-1627137, accessed August 20, 2015

Conectas Human Rights. 2012. Interview: views on the special police units for neighbourhood pacification (UPPs) in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, in Sur-International Journal on Human Rights, v.9, n.16, June 2012, pp. 202–211

Council on Foreign Relations. 2014. Battling for Brazil’s Favelas, available at http://www.cfr.org/brazil/battling-brazils-favelas/p33080, accessed August 21, 2015

Dowdney, Luke. 2003. Children of the drug trade. A case study of Children in Organized Armed Violence in Rio de Janeiro. Rio de Janeiro:7 Letras

Ferreira, Eduardo. 2015. ’Daqui a pouco vai ter outro no lugar dele’, diz Beltrame sobre Playboy. www.odia.ig.com, available at http://odia.ig.com.br/noticia/rio-de-janeiro/2015-08-10/daqui-a-pouco-vai-ter-outro-no-lugar-dele-diz-beltrame-sobre-playboy.html, accessed August 21, 2015

Freire-Medeiros, Bianca. 2013. Touring Poverty. Routledge

Griffin, Jo. 2014. Rio’s favela dwellers fight to stave off evictions in runup to Brazil World Cup, www.theguardian. Available at http://www.theguardian.com/global-development/poverty-matters/2014/jan/17/rio-favela-evictions-brazil-world-cup, accessed August

Hearst, Chesney. 2015. Early education opportunities lacking in Rio’s Favelas. www.riotimesonline.com, available at http://riotimesonline.com/brazil-news/rio-politics/early-education-opportunities-lacking-in-rios-favelas/, accessed August 20, 2015

Ivins, Courtney. 2013. Gender and the geopolitics of urban space. Observations from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, with cross-references from Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Master thesis, PUC-Rio

Leeds, Elizabeth. 1996. Cocaine and Parallel Polities in the Brazilian Urban Periphery: Constraints on Local-Level Democratization. Latin American Research Review 31 (3):47–83

Leite, Márcia. 2012. Da “metáfora de guerra” ao projeto de “pacificação”: favelas e políticas de segurança pública no Rio de Janeiro. Rev.Bras.Segur.Pública. São Paolo, v.6, n.2, pp. 374–389

Leite, Renata. 2011. Rocinha descobre o preço de regularização. www.oglobo.com, available at http://oglobo.globo.com/rio/rocinha-descobre-preco-da-regularizacao-3331304, accessed August

Marinho, Glaucia, Campagnani, Mario, and Cosentino, Renato. 2014. Brazil in Paula, Marilene de. (org.) World Cup for whom and for what? A look upon the legacy of the World Cups in Brazil, South Africa and Germany. Marilene de Paula e Dawid Bartelt (organizadores). – Rio de Janeiro : Fundação Heinrich Böll, 2014.

Mundoreal, 2012 “Corruption and the paradox of the UPP in Rocinha and Rio de Janeiro, www.Mundoreal.org, available at http://mundoreal.org/corruption-and-the-paradox-of-the-upp-in-rocinha-and-rio-de-janeiro-2, Last accessed August 19, 2015

— About Rocinha, available at http://mundoreal.org/about/about-rocinha, accessed August 20, 2015

— Corruption and the paradox of the UPP in Rocinha and Rio de Janeiro. Available at http://mundoreal.org/corruption-and-the-paradox-of-the-upp-in-rocinha-and-rio-de-janeiro-2, accessed August 20, 2015

Penglase, Ben. 2010. The Owner of the Hill: Masculinity and Drug-trafficking in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. The Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Anthropology, Vol. 15., No.2, pp.317–337

Rocha, Carla, Selma Schmidt and Sergio Ramalho. 2014. Beltrame sobre 5 anos de UPP: ‘Daqui a 20 anos, o que será da favela? www.oglobo.com, available at http://oglobo.globo.com/rio/beltrame-sobre-5-anos-de-upp-daqui-20-anos-que-sera-da-favela-11056774, accessed August 20, 2015

Rother, Larry. 2012. Brazil on the Rise: The Story of a Country Transformed. St. Martin’s Griffin

Rinaldi, Alfred. 2014. New Report Shows Crime on the Rise in Rio. www. riotimesonline.com, available at http://riotimesonline.com/brazil-news/rio-politics/new-report-shows-crime-on-the-rise-in-rio/, accessed August 20, 2015