Has the EITI been successful? Reviewing evaluations of the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative

How to cite this publication:

Päivi Lujala, Siri Aas Rustad, Philippe Le Billon (2017). Has the EITI been successful? Reviewing evaluations of the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative. : (U4 Brief 2017:5)

Has the EITI been successful? Many efforts have been devoted to improving resource governance through the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative. A review of 50 evaluations concludes that the EITI has succeeded in diffusing the norm of transparency, establishing the EITI standard, and institutionalizing transparency practices. Yet, there remains an evidence gap with regard to the mechanisms linking EITI adoption and development outcomes. Addressing this gap will require developing a theory of change for the EITI and demonstrating causality through more sophisticated methods. The cost-effectiveness of the EITI will also need to be compared to other policy options.

Introduction

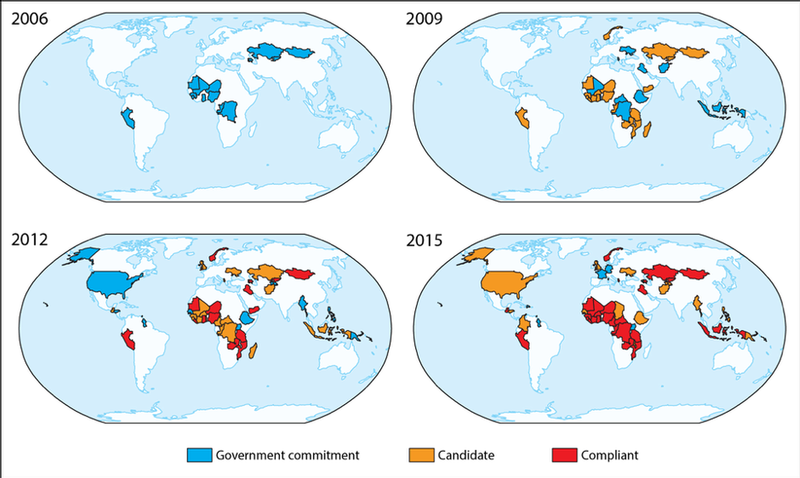

Conceived in the late 1990s and launched in June 2003, the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) has been a hallmark of international resource governance efforts and is now a global standard for transparency in extractive sectors. Initially designed as a voluntary process of extractive sector revenue disclosure for payments from companies to governments, the EITI has evolved into a broader instrument seeking to improve transparency and accountability within the natural resource management value chain, including corporate beneficiary ownership. A large number of resource dependent governments have committed to the EITI, which receives extensive support from donors, non-governmental organizations, and extractive industry companies. At the moment, the EITI has 52 members spread across all four major continents, including several high-income countries such as Norway, the United Kingdom, and the United States (Figure 1).

Despite this widespread support, and more than a decade of implementation, many researchers, practitioners, donors, and decision-makers alike are asking to what extent the EITI is achieving its goals and having a measurable impact on resource governance. The tasks at hand for the EITI – a relatively small international initiative – are indeed daunting given the sheer size of the targeted revenues (about 3.5 trillion dollars per year) and the vested interests of powerful actors involved (including some of the richest governments and largest corporations). Furthermore, turning around the poor developmental outcomes of ‘resource rich’ countries also requires addressing many other factors besides revenue transparency and resource governance. In this light, any evaluation of the EITI should take these into account when judging the success and progress of the initiative.

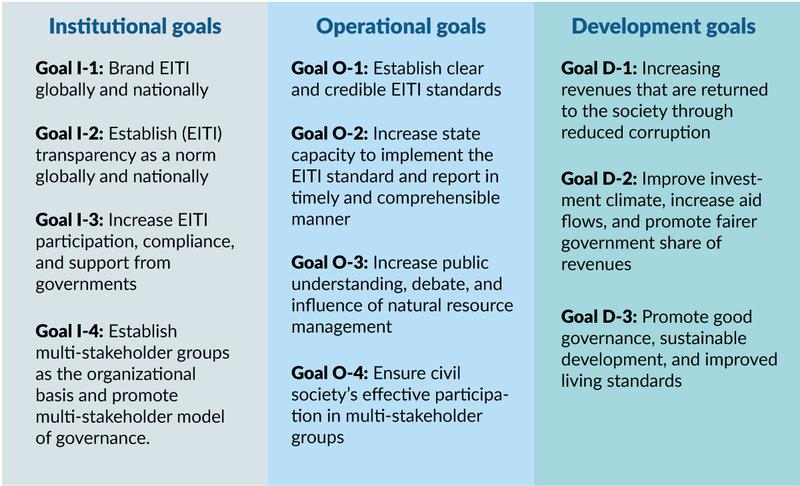

The EITI goals

The EITI has articulated 11 specific goals, falling into three broad categories (see Figure 2). These goals are set out in the core EITI documents – the EITI Principles, the EITI Articles of Association, the EITI Requirements, the Overview of Validation, and the protocol on participation of civil society – all of which were included in the EITI Standard 2016.

Institutional goals are about establishing the EITI as an organization and consolidating its position and its approach and functioning: becoming a recognized brand, consolidating transparency as a global norm, and establishing multi-stakeholder groups (MSG) as the organizational basis.

Operational goals refer to a set of goals about what the EITI is to produce. These comprise immediate EITI outputs and outcomes such as establishing the EITI Standard, publishing the annual national EITI reports, enhancing public engagement in resource governance, and ensuring civil society participation in national MSGs.

Developmental goals contain the broader and more long-term outcomes of meeting the needs of society. For the EITI, these include the goals of reducing corruption, increasing natural resource revenues accruing to the government, improving resource governance, and promoting social and economic development.

Figure 2. The EITI goals

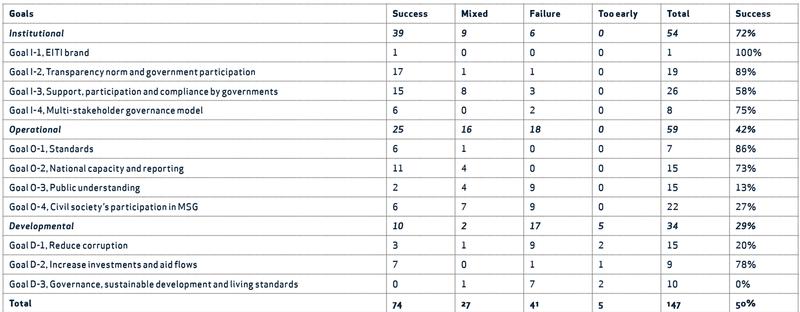

EITI achievements

By early 2017, a total of 50 studies, either independent or commissioned by the EITI, had attempted to assess one or several of the EITI goals included in Figure 2. Table 1 sums up the findings of these studies, with assessments being characterized as either success, mixed (i.e. diverse outcomes within study sample, suggesting a partial success), or failure to reach specific goals. The table also notes when the study concluded that the analysis was ‘too early’ to strongly conclude on the findings. Although we provide an overall ‘success’ percentage for each goal, those figures only provide an idea of aggregate findings across relevant studies, but one should refer to the online appendix to better account for variations in the studies’ scope, methods, timeframe, sample size, and quality. As such, these aggregated assessments need to be treated with caution.

Institutional goals

Among the three broad goal categories, the EITI has been most successful in reaching its institutional goals, notably by becoming a recognized brand and consolidating transparency as a global norm (Goals I-1 and I-2). There has been no study assessing the recognition of the EITI ‘brand’ at the international level, but several indicators suggest that it has achieved a relatively high level of recognition. The EITI returns about 10 million hits on Google, about twenty times more than that Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) founded in 1997, and thirty times more than the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme (KPCS) against ‘conflict diamonds’ created at about the same time as the EITI. The EITI has been endorsed once by the UN General Assembly, at least three times by the G20, and ten times by the G7/G8. This institutional branding success has been celebrated for its own sake. The success of EITI branding at the national level is more difficult to assess, but many efforts have been devoted by the national EITIs to getting the EITI better known and having revenue information more frequently accessed by local populations.

Since about 2012, the adoption of the EITI has spread from mostly low-income and aid-dependent African countries to middle-income countries across all four major continents. (Figure 1). Thus, the existing evaluations deem the EITI relatively successful in increasing EITI participation and support from governments (Goal I-3). However, several evaluations consider the EITI either a failure or a mixed outcome in terms of country participation by pointing to the lack of adoption by some resource-rich countries that are also considered to be highly corrupt. Some of these countries include the petro-states in the Middle East and North Africa. Some evaluations also point at the ability of many governments to delay the actual implementation of the EITI and suggest that institutional adoption is mostly driven by external pressures – such as foreign aid dependence or the need for diplomatic and security support.

Beyond the EITI itself, the initiative has also played a role in promoting and legitimating transparency as an international norm of governance, including through other resource revenue transparency instruments in the EU, US and Canada, as well as greater reporting by private and state-owned companies around the world. An indirect institutional contribution of the EITI has been to refine multi-stakeholder governance that came to prominence in the 1990s as a result of the ‘good governance’ agenda. In this respect, the EITI has frequently been touted as a novel and effective model of ‘tripartite’ governance between governments, companies, and CSOs, and the evaluations find that the EITI has been successful in institutionalizing of multi-stakeholder governance mechanism (Goal I-4).

Among the three broad goal categories, the EITI has been most successful in reaching its institutional goals, notably by becoming a recognized brand and consolidating transparency as a global norm

Operational goals

Operational goals consist of intermediate measures deemed necessary for the EITI to attain its broader developmental goals and relate to aspects that the EITI can directly produce or influence. As Table 1 indicates, the EITI assessment studies generally point to more failures with respect to EITI operational goals as compared to institutional goals. This difference reflects in part country level constraints in terms of policy buy-in, local capacity, and funding availability for implementation.

The EITI has been fairly successful in setting up standards for auditing and reporting (Goal O-1). The definition and implementation of transparency standards have been a major objective and operating mode for the EITI, for which the initial goal was to reduce corruption in extractive industries revenue management. The scope of the requirements was repeatedly criticized in the EITI’s early years for the data requirements not being detailed enough and for the EITI’s narrow focus on revenues flowing from companies to government, but the EITI Standard has since evolved to cover several other aspects of the natural resource value chains.

Overall, the EITI – including through the support of its International Secretariat and national-level organizations – seems to have increased timely reporting in the member countries, and thus has been successful in achieving the goal of national implementation of EITI Standard (Goal O-2).

There is so far little systematic evidence that the EITI has been successful in promoting public debate about, and action for, better natural resource governance (Goal O-3). This absence of evidence is in contrast to general perception that the EITI has contributed to international and domestic debates on resource governance. One possible reason for this lack of evidence is that civil society – and even more so the ‘public’ in general – is a diverse entity with dissimilar, and sometimes conflicting, objectives and expectations with regard to natural resource governance in general, and in particular with regard to how resource revenues should be distributed and invested. Two other possible reasons are that the EITI has to a large extent been a national-level initiative – with mostly technical discussions involving experts and activists – and little apparent relevance for the general public’s needs when it comes to information and changes to natural resource governance at the local level. Further, while the public may be well aware of resource revenue mismanagement, the space for public engagement can be severely limited due to repression or coercive forms of influence exerted by the central government, local authorities, and in some cases by traditional leaders.

The EITI has had some success in terms of civil society groups’ participation in the MSG (O-4). There is good evidence that the EITI has been successful in establishing the MSGs in the implementing countries and that MSGs often provide one of the very first opportunities for many civil society organizations to directly discuss natural resource governance with the government and extractive industries, and to acquire expertise on these issues, which they can then use more broadly. However, to what degree MSGs are addressing governance gaps in terms of inclusivity and accountability is questionable, as civil society is in many countries either under or mis-represented within MSGs, and has limited power to influence the other stakeholders.

Development goals

Developmental goals are, by nature, more long-term than the operational goals, but they also represent the concrete changes that populations would expect from ‘better governance’. Developmental goals, however, are – at least partially – beyond EITI’s direct reach, as they frequently rely on additional factors than EITI-improved resource and resource revenue governance. Whether the EITI has had an impact on developmental goals also remains an open question, as it is challenging to identify the correct measurements for impact, and many evaluations assess goals that are over-inflated compared to what the initiative formally alone can, such as testing for the effects of the EITI on overall quality of governance and poverty reduction.

Increasing natural resource revenues through reduced corruption (Goal D-1) has been the foundational goal of the EITI and the one with the highest public profile. There is some evidence that the EITI may have had a positive impact on reducing corruption in some countries, but this anti-corruption impact of the EITI seems to be context-dependent, for example, limited to countries with strong civil society, and there is little evidence for general reduction of corruption in the EITI member countries. In addition, distinguishing between extractive sector corruption and overall levels of corruption remains a methodological challenge.

Increasing foreign direct investments into member states’ resource sectors is another goal associated to the EITI. Implementation of the EITI is expected to send out a signal to investors that these countries are safer places to invest. This signalling has at times been amplified by international financial institution using EITI implementation as a condition for their support, thus pressuring governments to join the initiative and extractive companies to promote EITI adoption by their host government. There is relatively strong evidence that the EITI member countries receive more FDI after they become members and there is also evidence that this is also the case for foreign aid. Yet, no studies have been conducted to determine whether the EITI increases the share of revenues accruing to the government, an important dimension within the rationale of FDI-driven extractive sector growth.

While the EITI does not make strong claims about contributing to societal development such as poverty reduction and improved living standards, it is clear from the EITI Principles and the EITI Articles of Association that this is a long-term goal (Goal D-3). Currently, there is little evidence that the EITI has contributed to improvement in development outcomes. In any case, it would be difficult to isolate EITI’s causal impact on development goals given the diversity of factors at play and their interlinkages. However, assessing the broad developmental goals of the EITI remains a worthy enterprise, especially in light of the EITI’s own objectives. Yet, given the broad scope of expectations associated with EITI societal development goals, and the strong likelihood of seeing these goals being affected by factors independent from the EITI, evaluations of developmental goals will have to be cautious and qualified when qualifying the EITI as a success or a failure in this respect.

Recommendations for future evaluations and research on the EITI’s impact

Donors are understandably concerned about the success of the EITI, and about the documentation of achievements. They can, however, play an important role in requiring and supporting high quality evaluations to enable better-informed decision-making and measurement of achievements over time and space. At this point, it remains difficult to provide an overall assessment of the EITI based on past evaluations. Many studies have suffered from constraints when it comes to methods, short time frames and focus on early EITI period, sampling, outcome selection, and over generalizations of the results. Previous works have not built a testable theory of change for developmental goals nor systematically evaluated detailed sub-goals and local context factors. The following recommendations address some of these shortcomings.

Whether the EITI has had an impact on developmental goals also remains an open question

Evaluations should be more specific about what they assess, both in terms of measured outcomes and mechanisms tested:

Outcomes: i) measure the effects of the EITI on resource-related corruption, rather than on country’s overall corruption; and ii) parcel out the effects of the EITI on specific developmental outcomes, including resource revenue spending on health, education and poverty reduction rather than broad development indicators.

Mechanisms: measure the effects of increased transparency i) on the decision-making calculus of ruling elites, including over corrupt behaviour and accountability provisions; and ii) on the level and character of public debates and mobilization, including by specific audiences (journalists, parliamentarians, citizens, local authorities), and over demands for accountability.

Evaluations should be methodologically more sophisticated

Influences: evaluations need to account for the potential influence of other factors than the EITI in achieving or failing to reach specific objectives, including simultaneous but non-EITI related changes in governance and society.

Multiple scales: evaluations should account for the involvement of various levels of government in resource governance and revenue management, and the various processes occurring at, and between different scales, including local, national and international.

Methods: impact evaluations can mobilize methods with higher levels of discrimination over causality, including Randomized Control Trials.

Evaluations should consider crucial issues in assessing the effectiveness of the EITI

Theory of change: develop and test a detailed theory of change, which can be then be assessed in specific contexts.

Government revenue: assess whether and why the EITI increases the share of revenues accruing to the government.

Policy options: compare the impacts and cost-effectiveness of implementing the EITI Standard vis à vis other targeted natural resource governance interventions.