Eastern Sudan: Hosting Ethiopian refugees under tough conditions

Background: Hosting Ethiopian refugees in Gedaref State

Refugees’ coping strategies under harsh living conditions

How to cite this publication:

Adam Babiker, Yassir Abubakar, Mutassim Bashir, Abdallah Onour (2021). Eastern Sudan: Hosting Ethiopian refugees under tough conditions. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute (Sudan Brief 2021:2)

Many communities in Eastern Sudan host a large number of Ethiopian refugees. Conditions in the refugee camps are extremely harsh, and there is widespread fear within the host communities that the presence of refugees will have a negative impact on everyday life. To improve the poor conditions in the camps and relieve the tensions between refugees and the host communities, a closer collaboration between state authorities and stakeholder organizations is paramount.

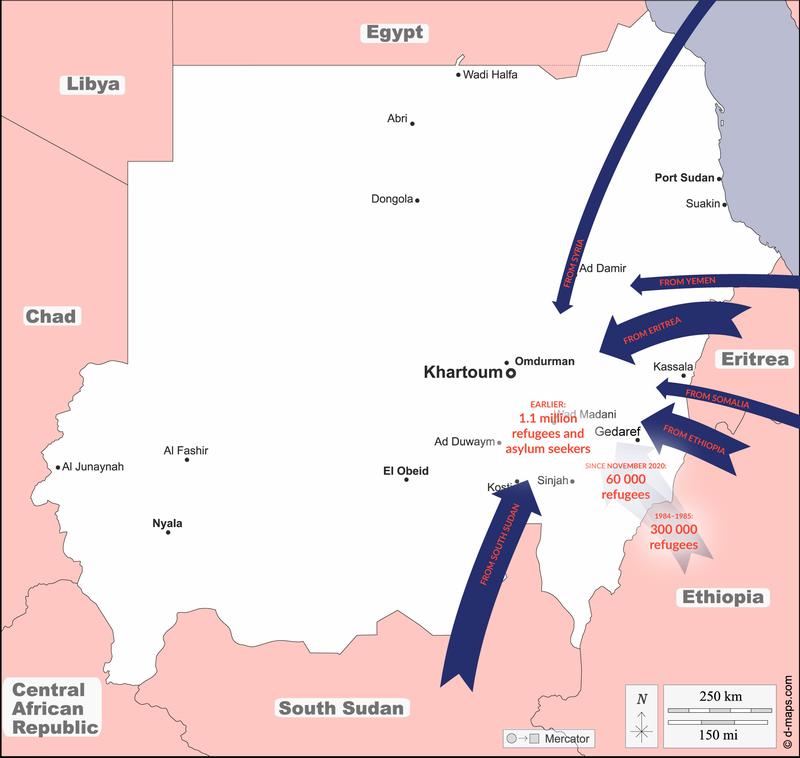

Since early November 2020, communities in Eastern Sudan bordering Ethiopia have received up to 60.000 refugees fleeing from the ongoing conflict in Tigray in northern Ethiopia. Sudan is however not new to the role of hosting refugees. Prior to the conflict in Tigray, Sudan was hosting approximately 1.1 million refugees and asylum seekers from South Sudan, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Syria, Somalia and Yemen. These were hosted in various Sudanese states: in Eastern Sudan (Red Sea, Kassala, Gedaref), in White Nile State, Khartoum and South and West Kordofan states. Historically, Eastern Sudan has had one of the most protracted refugee situations in the world, starting with the first influx of Eritrean refugees more than 50 years ago. The famine in Northern Ethiopia in 1984-85 resulted in 300.000 Ethiopian refugees, the majority from the Tigray. More than 40% of the refugees have been in asylum in Eastern Sudan for over 20 years. While many of the Tigrayans returned, most of Eritrean refugees stayed because of the dire conditions in Eritrea.

The new influx of Ethiopians into Eastern Sudan in 2020 is therefore happening in a context where the host communities are used to receiving refugees. This does not mean, however, that the host communities are in any way prepared for or have sufficient resources or a strong enough apparatus for receiving the refugees. In this brief, based on fieldwork in different camps and host villages in Kassala and Gedaref in 2020 and 2021, we present the challenges faced by both the host communities and the refugees. Through qualitative interviews with Ethiopian refugees, host communities, local government and camps authorities, and representatives of international organizations, we identify steps that need to be taken to improve the situation for both Sudanese and non-Sudanese living in the area.

Background:

Hosting Ethiopian refugees in Gedaref State

The Ethiopian refugees are settling in different types of facilities, with varying links to the host communities. Some of them have settled in what has been termed ‘closed camps’. These are former refugee camps, officially closed down by UNCHR and Sudanese authorities between 2001 and 2004 after the collective refugee status of Ethiopians and Eritreans was revoked. In these closed camps, the UNHCR does not provide any kind support for the refugees. The inhabitants in these camps are however in closer interaction with the neighbouring villages than refugees in regular camps are. In the closed camps Sudanese, Eritreans and Ethiopians live side by side. Some of them marry each other. They may even have access to government services. In recent years, a few organizations and agencies have started providing assistance to the former refugees in the closed camps through a numbers of programs in agriculture, livelihoods, and community development.

Other refugees arrive in recently constructed camps, with few or no historical connections to the neighbouring communities. Being secluded from the local community, these refugees depend on some services and assistance from Sudanese authorities and international agencies. As demonstrated below, this assistance does not provide the refugees with the needed health services, and the food aid provided is not sufficient.

Refugees’ coping strategies under harsh living conditions

Our study is one of the first to examine the impact of the influx of Ethiopian refugees on the host communities and the governments of Gedaref and Kassala.

Through field visits and interviews with refugees and host communities in and around Hamdayet reception centre in Kassala state, and Village 8 (the Al-Hashaba camp), the Umrakoba camp and Basanga reception centre and camp in Basunda, all in Gedaref state, a clear picture emerged: the refugees live under extremely hard physical conditions, with lack of basic infrastructure and access to health services. This has an immediate impact on the host communities, creating extra pressure on an already fragile economic and environmental situation in Eastern Sudan. Host communities have for instance recently complained about thefts, a phenomenon entirely new to the villagers. To the degree the accusations against refugees are correct, they may be seen as an indication of the hardship that they experience in the camps.

Many refugees have adopted a number of short-term strategies to adapt to the new situation. Some have contacted their relatives and acquaintances in order to get money to cover their needs, others have sold assets which they had brought from Ethiopia. Some have established small markets inside the camps, while others have gone to work as agricultural laborers in the agricultural schemes and farms near their camps, or cut wood from the nearby forests as a source of income.

The refugees’ coping strategies do not lessen the burden of their difficult health conditions in the camps though. The poor health conditions are reinforced by the fact that many of the refugees were already malnourished and food insecure before they left Ethiopia. The lack of coordination in provision of services between the different governmental institutions and national and international organizations further exacerbate the situation. One of the main problems facing the refugees in the camps is the scarcity of drinking water. Furthermore, medical staff working in the camps report many cases of fever among the refugees, but the underlying causes of fever cannot be diagnosed due to a lack of technical equipment.

Some of the refugees brought their livestock across the border. The animals in the camps have not been tested for disease or vaccinated, hence constituting a breeding ground for insects that potentially carry disease, such as the sand fly (Kala azar) and mosquitoes which can transfer a number of diseases to humans. The increasing number of house flies in the camps is a clear indication of a deteriorating environmental health situation characterized by overcrowding, lack of latrines and scattered amounts of refuse and human waste inside the camp. Different types of diarrhoea are spreading throughout the camps because there is no opportunity to isolate people who are sick pending their transfer to the state hospital. A rising number of undiagnosed patients with upper respiratory tract infections is also of growing concern in the context of the covid-19 pandemic.

Total numbers of refugees in Eastern Sudan

|

No |

Camps |

State |

Number |

Ethnicity |

|

1 |

Hamdayet |

Kassala |

6192 |

Tigray |

|

2 |

Shagarb |

Kassala |

94 |

Tigray |

|

3 |

Village 8 |

Gedaref |

3093 |

Tigray |

|

4 |

Basanga |

Gedaref |

1449 |

Kimant |

|

5 |

Basunda |

Gedaref |

552 |

Kimant |

|

6 |

Um Rakooba&Tenidba |

Gedaref |

41714 |

Tigray |

|

7 |

Um Gargour |

Gedaref |

120 |

Tigray |

|

8 |

Taya & Um Diblou |

Gedaref |

1409 |

Gumuz |

|

9 |

Camp 6 |

Blue Nile |

152 |

Tigray |

|

10 |

Camp 6 |

Blue Nile |

2360 |

Gumuz |

|

The Total |

57135 |

|||

Source: Sudanese Coordination Office for Refugees (COR) daily report, 26 September 2021.

Host communities’ perceptions of refugee impact

The recent influx of Ethiopian refugees has had a palpable social and economic impact on the host communities. Many express fear that the presence of large numbers of refugees who have different traditions and values from their own could be a threat to their way of life. As the majority of Ethiopian refugees are Orthodox Christians and the Sudanese hosts are Muslims, their traditions and values are perceived to be very different, especially with regard to the relationship between men and women. Local inhabitants also express concern for the potential for various types of social disruption stemming from the difficult life at the camp, for instance child labour, spread of arms and human trafficking, and violence as a result of disputes between Ethiopians from different ethnic groups. The host communities have expressed worries about their children’s future. A father from Village 8, for instance, stated that "our children are less positive towards education now, as they see new income opportunities in newly-made markets in camps as an alternative to school. Not only that; we worry that our children may be influenced by the new culture of of boys and girls mingling that they observe in the camps."

Host communities also express concern for the environment and the economy in and around the camps. They claim that the refugees’ livestock have begun to feed on the agricultural crop of the Sudanese farms in the area. These rumours, true or not, have led to disputes between the refugees and Sudanese farmers. Refugees offering cheap wage labour is perceived to decrease the chances of employment for local people. However, this is not a new phenomenon. Ethiopian migrants have a long history of working as seasonal agricultural labourers in Eastern Sudan. They have for instance constituted a major share of the labour force in the government-run agricultural schemes in Gedaref. When arriving as refugees in November 2020, many former labour migrants used former networks to get work for themselves and fellow refugees on the farms. As such, the new influx of refugees merely feeds into already established patterns of labour migration.

In general, the presence of refugees is seen to contribute to the increase in supply and prices of some goods as well as the decrease of others. In Village 8, for instance, some of the citizens rent their houses to rich Ethiopian refugees, creating new dynamics in the house renting market in the area. A more long-term concern among the host communities is that refugees will move out of the camps due to the unfavourable conditions there. Refugees often claim that they have relatives living in nearby villages or towns as a way of getting out of the camps. But the unrestricted movement of refugees to and from the camp exposes them to human traffickers or exploitation by farm brokers looking for cheaper labor.

Conclusions and recommendations

Our findings clearly show that a general improvement of the camp conditions will be beneficial both for the refugees and the host communities Firstly, the provision of sufficient services in the camps (e.g., well-equipped healthcare center, schools, entertainment, etc.) will help to cover the basic needs of the refugee population. Secondly, satisfactory services in the camps may also make the refugees want to stay put instead of leaving the camps. Staying in the camps will provide protection from human traffickers or labour exploitation. Thirdly, if the refugees get sufficient services in the camps, they will not have to rely on the meagre government services in the host community, thereby lessening the burdens on the local communities in Eastern Sudan.

The following steps should be taken to improve conditions in the refugee camps:

The governments of Kassala and Gedaref and the Sudanese Commission for Refugees (COR) should urge the United Nation’s refugee agency, the UNHCR, to collaborate with stakeholder organizations and agencies to cater to the needs of both refugees and host communities.

In order to address the short-term and long-term challenges facing refugees and host communities, the governments of Kassala and Gedaref and the COR should form a coordination council with effective responsibilities, including all national and international organizations involved in refugee work in Eastern Sudan.

In order to improve the dire health situations in the camps, all healthcare centres and clinics inside the camps should receive adequate equipment as soon as possible. Healthcare centres that are meant to serve host communities are also key to surveying diseases among refugees. These centres should benefit from the expertise of national and international organizations and receive assistance to overcome the current situation.

Involving the host communities in refugee issues, services and affairs will benefit the communities and facilitate a better relationship between the refugees and the hosts. Genuine engagement can reduce tension based on different religious and cultural practices and gender norms, and help refugees and hosts interact in a way that contributes to contain the spread of weapons and human trafficking in Eastern Sudan.

The Center for Refugees, Migration and Development Studies (CRMDS), Faculty of Community Development, University of Gedaref has delegated a dedicated research team to study issues of on-going Ethiopian refugees’ influxes into Gedaref. The influx occurred due to recently erupted conflict between Ethiopian Federal Government Forces (ENDF) against Tigray region government which led by Tigray Peoples Liberation Front (TPLF). The research team was formed of the following members: Mr. Adam Babiker (CRMDS Coordinator), Dr. Yassir Abubakar (Dean, Gadarif Regional Institute of Endemic Diseases), Mr. Mutassim Bashir and Mr. Abdallah Onour (Lecturers at Department of Sociology and Anthropology, University of Gadarif). The study was conducted by CRMDS in collaboration with the Assisting Regional Universities in Sudan (ARUS) Project; whereas the latter generously funded the study in addition to the following stakeholders’ meeting.