EFFEXT Background Papers – National and international migration policy in Jordan

Part I: National migration policy

Jordan as a refugee-hosting state

Jordan as a migration sending country

How do government, stakeholders, and populations react?

Migration governance structure

Human trafficking / smuggling policy

Emigration and diaspora policy

Part II: International migration policy relations

Europe-Jordan relations and migration policies

EU-Jordan Association Agreement (1997, in force 2002)

About the EFFEXT Background Papers

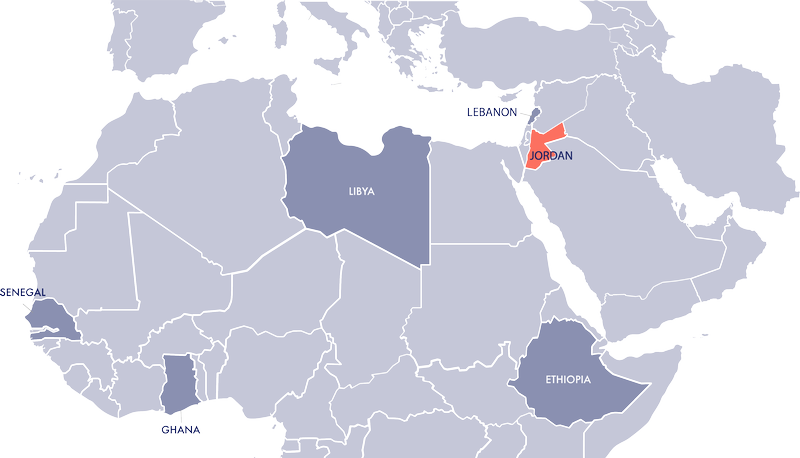

The Effects of Externalisation: EU Migration Management in Africa and the Middle East (EFFEXT) project examines the effects of the EU’s external migration management policies by zooming in on six countries: Jordan, Lebanon, Ethiopia, Senegal, Ghana and Libya. The countries represent origin, transit and destination countries for mixed migration flows, and differ in terms of governance practices, state capacities, colonial histories, economic development and migration contexts. Bringing together scholars working on different case countries and aspects of the migration policy puzzle, the EFFEXT project explores the broader landscape of migration policy in Africa and the Middle East.

The EFFEXT Background Papers guide the fieldwork, case selection and analysis of migration policy effects in the EFFEXT project’s case countries. The papers are based on desk-reviews of scientific literature and grey literature, the latter including government documents, governmental and non-governmental reports, white papers and working papers.

This EFFEXT background paper provides a brief presentation of migration and migration policy dynamics in Jordan. It presents an overview of key national and international migration policies, and outlines the key migration governance structures in Jordan. In terms of international relations, the paper primarily focuses on Jordan’s collaboration with Europe and more specifically, the EU. The paper concludes with a short reflection on the future of the EU-Jordan partnership.

Part I: National migration policy

Introduction

Jordan’s migrant population accounts for an estimated 2–3 million people, including between 650,000 – 1.4 million Syrian refugees, 100,000 refugees of other nationalities, and an estimated total of 540,000 migrant workers, of whom approximately 315,000 are registered (ILO 2017). These figures do not include the large Palestinian-origin population in Jordan, of whom 2,366,903 are registered with the United Nations Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) in Jordan (UNRWA 2022). There are overlaps and transitions between the categories of labour migrant and refugee, and Jordanian national law does not contain an overarching provision to distinguish between different categories of migrants. However, in cooperation with the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR), a large body of regulations and exceptions have emerged that govern the refugee population as several distinct categories detailed below.

This background paper aims to provide a review of migrant and refugee policies in Jordan, in particular those that pertain to the European Union (EU). Based on a literature review of academic and grey literature, the paper first provides a brief description of the migration landscape in Jordan. It then outlines migration governance within the country, and maps key legislation and regulations adopted by the Jordanian government to manage migrants, including refugees, and their access to and presence in the country. The second part of the paper expands on Jordan’s international and regional relationships as they relate to migration, including an assessment of the relations between the EU and Jordan.

For the purposes of this paper, we use ‘refugee’ to refer to those who have been recognised as refugees by UNHCR – either prima facie as in the case of Syrians or on a case-by-case basis as for those of other nationalities – or who hold an asylum-seeker card (ASC) from UNHCR, or who are waiting for registration and assessment. This has been complicated by the request from the Government of Jordan for UNHCR to not register asylum seekers who officially entered Jordan for medical treatment, study, work, or tourism before claiming asylum, primarily affecting non-Syrian refugees (HRW 2020). Where we refer to Palestinian refugees, this means Palestinians registered with UNRWA.

Migration patterns in Jordan

Jordan as a refugee-hosting state

Jordan has long-played an important role in hosting refugees and displaced populations from the Middle East and beyond. Perhaps most notably, Jordan has hosted a substantial Palestinian refugee population who fled in 1948, and in 1967. There are currently an estimated 2.4 million Palestinian refugees in Jordan (UNRWA 2022) and 19,000 Palestinians from Syria (PRS) (UNRWA 2023). Palestinians occupy a unique and complex position within Jordan, with many Palestinian-origin populations holding Jordanian nationality, while others remain as refugees without a Jordanian ID and with limited access to employment and services. Status is determined by place of origin within Palestine, as well as the date of flight. Those who arrived in 1948 were granted Jordanian citizenship, which fathers can transfer to their descendants. As such, they may hold 5-year passports and are eligible for government services. Others, in particular Palestinians from Gaza – numbering up to 150000 – continue to be largely excluded from many protections and services (El-Abed 2006). Palestinian refugees are subject to a wide proliferation of frequently changing regulations (Davis et al. 2017). This history and continued Palestinian displacement are key in understanding policy attitudes towards other groups of refugees, and particularly the potential for long-term presence in the country (Lenner 2020).

More recently, Jordan has been known for hosting refugees fleeing the ongoing conflict in Syria. Currently, there are 660,000 Syrian refugees registered with UNHCR, though the Jordanian government estimated there to be 1.4 million Syrian refugees in the country as of 2015. Some of this discrepancy can be explained by government estimates that included Syrians who were already in Jordan prior to the start of the conflict (Arar 2017). Others have raised questions as to whether the estimate is inflated, as in the case of Iraqis, although this has been contested by government officials (Arar 2017; Seeley 2010; Ali 2021).

The country has also hosted large numbers of Iraqi refugees, displaced by the First Gulf War, the 2003 invasion of Iraq by the United States (US) and allies and, most recently, fleeing the Islamic State (ISIS) (Chatelard, 2002; Chatty, 2010; Stevens, 2013). As of the first quarter of 2023, there are 62,068 Iraqis alongside 12,771 Yemenis and 5299 Sudanese and smaller numbers of refugees from 53 other nationalities registered with (UNHCR 2023). Non-Syrian refugees are required to register as asylum-seekers and undergo refugee status determination processes. At times, there have been significant backlogs in this process resulting in delayed access to status and the associated services. Some protections, such as work permits, are not available to refugees of non-Syrian nationalities, and access to services including healthcare and education fluctuates. In recent years, there has been substantial advocacy for a One Refugee approach within Jordan that has made some progress in expanding assistance to refugees of all nationalities. Jordan hosts about 15 refugee camps for Syrian refugees, Palestinians, and Palestinian refugees from Syria. Refugees of other nationalities registered with UNHCR do not have access to camps, and the vast majority of refugees in Jordan live outside of camps.

Jordan as a transit country

Jordan is one of the largest refugee hosting countries in the world, with an estimated 1 in 10 people in the country being a refugee. However, Jordan largely considers itself as a transit country for migrants, adopting a policy of “letting them in but depriving them of a status, therefore encouraging them to move forward” (Chatelard 2002 pg. 9): Jordan does not recognise asylum-seekers, residency is restricted, and there are extremely limited routes to citizenship for migrants in Jordan. UNHCR’s operations in the country are also subject to the condition that refugees will be resettled to a third country, foreclosing the option for local integration, although this has rarely been met (Chatelard 2002). The potential – and stated expectation from Jordan – that refugees will move on from Jordan, plays an important role in shaping policies relating to migrants’ access to rights and services in the country, and in Jordan’s relationship with the European Union (EU). However, the EU is not always the preferred destination for onwards movement, due to the cost, dangerous routes, and concerns about cultural differences (Achilli 2016, Tyldum and Zhuang 2022). Perceived options for return, meaningful access to education and work have been shown to have some impact on migratory aspirations and realities (Tyldum and Zhuang 2022), and Kvittingen et al (2019) also demonstrate distinct patterns of secondary migration between Syrian and Iraqi refugees in Jordan.

Labour migration

In addition to the large refugee population, Jordan hosts a substantial labour migrant population. In the 1970s, labour migration from Jordan to the Gulf and growing wealth in Jordan resulted in an increasing number of migrant workers being brought to Jordan (ILO2017b). Recent estimates suggest that there are at least 540,000 migrant workers and estimations suggest a maximum of 1 million or 1.4 million migrant workers in Jordan (Global Detention Project 2020, ILO 2017a, ILO 2017b). Major sectors associated with migrant work include the construction sector (particularly for Egyptians); agriculture; and domestic work and the garment industry, which are typically associated with workers from South East Asia and female migrant workers (Almasri 2021; ILO 2017b).

Up until 2007 Jordan had largely maintained an open-door policy towards foreign workers, but from 2007 its approach became increasingly protectionist, with some professions restricted to only Jordanian nationals. Under the auspices of the Jordan Compact, work permits have been made available to Syrian refugees since 2016. In mid-2017, low uptake of permits resulted in the scheme being extended to camp residents, who had previously been excluded due to their identification as security risks by the Ministry of Interior and the dynamics of the Jordanian labour market (Lenner, 2020, Ali 2021, Turner 2015). More than 230,000 Syrian work permits have been issued (Stave, Kebede and Kattaa 2021), however this includes permits re-issued to the same individual following the expiry of their initial permit.

Alongside those holding formal work permits (whether or not they match with a worker’s occupation), there is a large informal workforce. It is estimated that refugees account for 20% of the non-Jordanian labour force in 2016 (ILO 2017b), with the remaining 80% composed of migrant workers. As with refugees, migrant workers in Jordan come from a wide range of countries, but the sector is dominated by Egyptian labour. Between 1994 and 2011, Egyptians accounted for 60% of all foreign nationals holding work permits (MPC 2013) and up to 68% of the migrant labour force in 2011, although this has now dropped to only one third (Kuttab 2020). Nonetheless, as of 2019, 223,000 Egyptians held a work permit, and it is estimated that three times as many were actually engaged in work, including in the informal sector (Kuttab 2020).

Jordan as a migration sending country

While the focus is often on Jordan as a recipient of migrants, it is also an important migrant-sending country in its own right, with 8% of the population understood to be living, working, or studying abroad (Diaspora for Development 2020). The 2022 Arab Barometer report for Jordan indicates that 48% of Jordanians have considered emigrating, the highest proportion among countries surveyed, continuing an upward trend observed in recent years (Arab Barometer 2022). Young people (aged 18–29), men, and those with a university degree are the most likely to wish to migrate (at 63%, 56% and 56%, respectively). Consideration of emigration should not be conflated with an active decision to migrate, nor the resources and capacity to do so, yet the figures reveal a high interest in movement amongst the population. Emigration patterns follow the geopolitical situation in the region and have fluctuated with oil prices, conflicts and economic development. For example, previous outward migrations corresponded with oil price increases in 1973, at which time many highly-skilled and Palestinian-origin Jordanians emigrated to oil-producing states (MPC 2013), followed by the return in the mid-1980s as Arab workers were largely replaced by Asian workers in the Gulf countries. An overwhelming majority (93%) of respondents in the 2022 survey indicated economic reasons as the primary motivation for their interest in migration, a trend likely to continue given economic pressures in the country (Arab Barometer 2022). Patterns of movement to the Gulf have continued, with the majority of Jordanian expatriates in Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (Diaspora for Development 2020; De Bel-Air 2016; Jordan Strategy Forum 2017), followed by the United States. Numbers vary, but between 75,000 and 100,000 Jordanian nationals live in the US and Canada (De Bel-Air 2016; Diaspora for Development 2020). Migration to the EU is of limited significance. Roughly 40,000 Jordanians were registered to be living in Europe of which nearly 9000 were in Germany and nearly 4000 in Sweden, with 7000 in the UK.

According to a survey conducted by the Jordan Strategy Forum in 2018, 66% of Jordanians working abroad held an undergraduate degree, 14.5% a master degree, and 3.9% a PhD. These figures are considerably higher than the rates for the Jordanian population overall (World Bank 2021). Most of the approximately 25,000 Jordanian nationals that study abroad do so in the US, followed by Egypt and Sudan (de Bel-Air 2019). There are about 1600 Jordanian nationals studying in the UK. Jordan is a member in the ERASMUS+ programme, and between 2014 and 2019, 2,603 staff and students from Jordan moved to Europe through an Erasmus+ programme (European Commission 2020).

Remittances make a relatively large contribution to Jordan’s economy, equating to 11.3% of GDP in 2021 (World Bank 2021b). Jordan does not have a diaspora engagement policy, however there is an active 5 Year Strategy and Plan for Expatriates (2019 – 2023) which builds upon a previous iteration (2014 – 2019) and aims to enhance the participation of nationals abroad in development initiatives in Jordan, improve services available to expatriates, enhance communication between expatriates and the homeland, and strengthen institutional capacities to efficiently serve expatriates (Diaspora for Development 2020).

How do government, stakeholders, and populations react?

Jordan has generally been widely lauded for its generous welcome of refugees. A fear of increased social tensions and economic competition is prevalent in government discourse, among international organisations and INGOs, who express concern that the protracted nature of the conflict and dependence on scarce local resources is impacting negatively on Jordanian attitudes towards Syrians (Baylouny 2020). Yet, high levels of tensions and outbreaks of violence between nationals and refugees, as experienced in Lebanon, are rare in Jordan. Despite a strong discourse of hospitality, refugees are frequently framed as security risks and an economic burden with substantial impacts on their access to services and their relationship with the Jordanian community and other migrant groups (El-Abed 2014). Nonetheless, blame has been apportioned to the Syrian influx for price increases, particularly for rent, water scarcity, and reduced access to state services, among other issues. Despite some instances of hostility, redress has primarily largely been sought from the state and INGOs (Baylouny 2020). Syrian long-term presence remains a taboo subject, and integration is not an overt policy goal. However, the public response should not be seen as monolithic, with differences in perceptions according to the nationality and perceived identity of migrant groups, geographic location, and pre-existing political, familial, and economic ties.

Refugees and labour migrants play an important role for Jordan. However, this is not fully recognised in official and public discourse around refugees who are instead portrayed as a significant cost for Jordan to bear (Ali 2021). This discourse distinguishing between Jordanians and foreign labour (which includes refugees) is also reflected in public society, beyond the niches which have experienced competition as a result of migration (Lenner 2020; Ali 2021). Jordan has been described as a rentier state, having successfully leveraged its position to attract high levels of funding and international support, ostensibly to support the hosting of refugees, but arguably in return for containing refugees. The common framing by the EU and Jordan of refugees in Jordan as an economic burden is discussed in greater detail in Section 2. Similarly, both Jordan and the EU regard forced migrants as a potential security threat (Chatelard 2002; Ali 2021), a point which we return to in Section 2.

Migration governance structure

Jordan is an electoral monarchy (Baylouny 2020). The King leads decision-making with regards to immigration and border policy, with the Chief of Staff and the Prime Minister also playing influential roles. Ministry heads, particularly of the ‘sovereign’ ministries (Ministry of the Interior, Ministry of Defence) play a large role in shaping policy, with these positions are appointed by the King (Ali 2021). Particularly with regard to employment policy, investors and business owners also contribute to policy discussions (de Bel-Air 2019).

Bel-Air (2019) identifies the following ministries as the key Jordanian institutions dealing with migration issues:

- Ministry of Interior (MoI): The Ministry of the Interior (MoI) maintains overall responsibility for security, border control, and immigration regulations. This includes issuing refugees with service cards (MoI cards) – biometric ID cards. The MoI also houses the Syrian Refugee Affairs Directorate (SRAD), established in 2014 and responsible for camp security and counting and registering Syrians (Ali 2021). Along with the General Intelligence Directorate and the Royal Court, they also deal with deportations.

- Ministry of Labour (MoL): The Ministry of Labour coordinates with other public sector bodies for the implementation of immigrant employment policies (de Bel-Air 2019), and is responsible for ensuring that employers follow regulations on working conditions. In August 2022, it was announced that the Ministry of Labour would be closed as part of a government efficiency drive, and its functions re-allocated. The issuing of foreign work permits is one key area that has been proposed to move to the MoI (Jordan Times 2022)

- Ministry of Planning and International Cooperation (MoPIC) describes itself as a “hub for local and international partners” (MoPIC 2023). It plays a key role in the management of Jordan’s refugee population through its oversight of the Jordan Response Plans and the coordination of international partners, civil society and other local partners in line with Jordan’s country vision. MoPIC chairs the Jordan Response Platform for the Syrian Crisis (JRPSC), the primary platform for coordination between the Government of Jordan, donors, UN agencies, and non-governmental organisations (NGOs). Within the platform, specific responsibilities categorised into task forces, with the leadership of each task force being held by the relevant sectoral line-ministries.

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Expatriates (MoFA) guides and develops relationships with other countries and external partners, including representing Jordan in global forums and in the development of international agreements. The ministry also has a responsibility towards Jordanian expatriates, and provides consular services to Jordanians abroad and foreigners in Jordan. The MoFA also hosts the Department of Palestinian Affairs supervises the administration of Palestinian camps in Jordan and coordinates with UNRWA for service provision in the country (DPA 2022)

Further to this, specific line ministries have a key role in responding to refugees. In particular, the Ministry of Education and the Ministry of Health have received substantial financial support for the expansion of their services to refugees. For example, between 2011 and 2018 (prior to the COVID-19 pandemic) the EU provided €138 million in budgetary support to the Ministry of Education and a further €22 million for scholarships and higher education (European Commission, 2018). Access to primary education and healthcare has generally been available for Syrian refugees (albeit with inequalities in quality and subject to changing regulations) (Shuayb et al., 2021). The same provisions have not been consistently extended to refugees of other nationalities (Johnston, Baslan and Kvittingen, 2019).

Municipalities play an important role in the implementation of the refugee response and work closely with international actors on specific initiatives. However, the Ministry of Local Administration (MOLA) is not seen as particularly influential within policy processes (Ali 2021), and within this framework most municipalities have a limited formal role in policy-making processes. Nonetheless, municipalities do conduct their own initiatives, including in cooperation with international actors, alongside the centralised framework (Ali 2021).

UNHCR has been operating in Jordan since 1991 (Chatelard 2002) and refugee policy implementation with regards to status determination is delegated to UNHCR, through a 1998 Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) and its update. The Government of Jordan continues to exert a significant influence over UNHCR’s activities in the country (for example, the current halt in registration of non-Syrians).

UNRWA has a long-standing presence in Jordan, and it is the agency’s largest field of operation with over 2 million people registered as refugees (although as noted above, many also hold Jordanian citizenship). Included within this are Palestinian Refugees from Syria (PRS). There are 10 Palestinian camps, accommodating an estimated 18% of the registered Palestinian population (UNRWA 2023). Within the camps, UNRWA provides a range of services, including primary education, healthcare, social security and social and community programming. Nonetheless, conditions in some Palestinian camps are extremely difficult (Kvittingen et al., 2019). UNRWA and the European Union have had a strategic partnership since 1971. The most recent joint agreement, signed in 2021, renews the EU’s commitment to supporting UNRWA politically and financially (Directorate-General for Neighbourhood and Enlargement Negotiations, 2021). In 2022, the European Union announced funding of €246 million to UNRWA for the following three-year period (2022 – 2024), with further funds dedicated to food security, making it the largest multi-lateral donor to the UN agency (UNRWA, 2022). In the same period, UNRWA estimated budgets for Jordan operations of $149,872,000 USD for 2022 and, $153,989,000 USD for 2023

National migration policy

Jordan does not have a unified national migration policy. Key regulations governing migrants in the country include:

- 1973 Law n°24 on Residence and Foreign Nationals’ Affairs, modified by Amendment n°90 of 1998, is the cornerstone of Jordan’s migration policy. Among other measures, it underpins regulations regarding the entry and exit of Jordan by foreign nationals (Article 4), residence permits (Chapter 3), and the penalties for violating these provisions.

- The kafala (sponsorship system): Foreign workers in Jordan are required to have a local sponsor (kafeel) (The Law on Residence and Foreigners’ Affairs (1973, modified in 1998) and the By-Law No. 3 of 1997 regulating Visa Requirements) (de Bel-Air 2019). Sponsors are responsible for permit fees, and in some cases travel expenses and housing. Migrants are tied to a specific employer, and may not transfer to a different employer, resign, or leave the country without written permission from their sponsor (ILO 2017b). In practice, this gives employers near complete control over employees’ work and immigration status and resulting in the potential for exploitation of migrants (Jones et al. 2022, ElDidi et al. 2022)

- The 1996 Labour law contains provisions for the recruitment of overseas workers. Overseas workers must obtain a work contract before departure through established Jordanian diplomatic and economic representations, and sponsors must ensure work permit fees are paid before departure. National applicants are given priority over foreign applicants, and 28 professions are closed to non-Jordanians (Kayed 2020). Initially, domestic services and agriculture – two of the largest sectors employing foreign nationals – were exempt from the 1996 Labour Law, but this was amended in 2008. Workers in these sectors require a work permit, but fees for work permits have varied in these domains. Since the introduction of Syrian work permits in 2016, new regulations for Syrian work permit holders have been introduced that include flexible work permits in some sectors (e.g. agriculture, construction), the permission to switch sectors without a clearance form when the permit expired, and the ability to switch employers without a release form (Stave, Kebede and Khattaa 2021). This has expanded access to the labour market, particularly for seasonal or temporary jobs, but there are concerns about access to social security and other labour rights for workers on short-term agreements. The Labour Migration Directorate sits within the MoL and is responsible for delivering work permits (de Bel-Air 2019). However, the dual role of the MoL as regulator of working conditions and enforcer of immigrant working regulations has been criticised as providing ineffective protections for migrant and refugee workers, who often work without permits (ILO 2017b).

- 1954 Law n° 6 on Nationality, amended in 1987 sets out who is eligible for Jordanian citizenship, and the limited routes through which non-Jordanians may apply for citizenship. Importantly, Jordanian nationality is only passed to children with Jordanian fathers. Jordanian mothers only transmit their citizenship to their children in case of the risk of statelessness and if the children are born in Jordan. There are some reductions in the length of continuous residency required to apply for naturalisation for Arab nationals and in the case of marriage (MPC 2013).

Jordan does not have a national law on refugees (Kelberer 2017). Rather, refugees’ presence in Jordan is generally governed by Law No. 24 of 1973 concerning Residency and Foreigners’ Affairs and its update. The 1952 Constitution of the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan Article 21 also ensures that refugees shall not be extradited on account of their political beliefs. However, there is a plethora of regulations and instructions managing subsequent exceptions and adaptations for specific groups of migrants and refugees, operating at different times, and in relation to specific issues, discussed further in the following section. A number of different governmental bodies work with refugees, but there is little overarching migration policy agenda in Jordan, outside of the Jordan Response Plans and the MoU with UNHCR, discussed further below. The Ministry of Interior (MoI), one of the principle bodies responsible for overseeing immigration policy, makes little mention of forced migration on its website or in the nascent strategic plan available.

Refugee policy

Refugee and asylum policy

Jordan is not a signatory to the 1951 refugee convention or its 1967 protocol and does not have an overarching refugee and asylum policy. The Government of Jordan does not recognise asylum seekers, but those fleeing war may find sanctuary and protection against refoulement (Tsourapas and Verduijn 2021), a protection that is also well established in customary international law and Jordan’s commitments to other international agreements (HRW 2006). Despite this, concerns have been raised regarding the presence and humanitarian access to Syrians in the Berm, a demilitarised ‘no-man’s land’ at Jordan’s northern border with Syria, and the extent to which these populations should be considered as being within Jordan’s territory, returns to the informal Rukban camp (Edwards and al-Homsi 2020), and the ramifications of moving aid distribution points further away from Jordan’s border as a form of forcible movement of populations (Humanitarian Foresight Think Tank 2017; Simpson 2018).

Asylum claims and refugee protection are managed through a MoU between the government and UNHCR. UNHCR has been operational in Jordan since 1991, in response to influxes due to the First Gulf War, and the MoU was signed in 1998 and updated in 2014 (UNHCR 2013). The MoU contains some of the same definitions and provisions as the UN Refugee Convention, but such protections are not guaranteed through changes in legislation (Frangieh 2016; Clutterbuck et al 2021). The relationship between UNHCR and Jordan with regards to protection space has, at times, been contentious (Stevens, 2013), yet certain rights and services (education, healthcare, work) are accessible, albeit typically of lower quality, and are not equally accessible to different nationalities. The 2014 update demonstrates a willingness from parties to persist with the minimum protection offered through the agreement, despite its challenges. The MoU also commits UNHCR to resettling refugees (despite this being outside of the full control of UNHCR). Frangieh (2016) argues that the MoU should be considered as a tool to find solutions for people in transit and to shift responsibility from the state to UNHCR, rather than a response to large-scale displacement.

The response to Syrian refugees in Jordan is guided by the Jordan Response Plan to the Syria Crisis (JRP), beginning in 2015 and providing a 2-year plan of action for the response. Within the JRP, heads of ministries lead sector-specific task forces, with some degree of discretion in the pronouncements made by each ministry. Together, these instruments provide a framework for basic protection of asylum seekers and refugees in Jordan. However, it also leaves scope for substantial flexibility in Jordan’s approach, which can be seen in the different provisions for different national groups, and the relatively frequent changes in provisions and services for different groups. The widespread use of announcements and regulations (rule by decree) – for example, education for particular refugee groups has previously been granted through announcements by the Minister for Education, rather than through an established legislation – rather than legislative change results in refugee governance that is highly flexible for the government, yet often seen as unpredictable and uncertain for refugees (Canefe 2016).

The response to refugees in Jordan ensures inclusion of vulnerable Jordanians, at a minimum 30:70 assistance split between Jordanians and refugees. Refugees are not eligible for social protection programming provided by the Ministry of Social Development of the Kingdom of Jordan (MoSD) (Röth et al. 2017), although a small pilot “Estidama++ Fund – Extension of Coverage and Formalization” was announced in 2022 to support contributions to the national social security system for vulnerable Jordanians and non-Jordanians, including refugees (ILO 2022).

Jordan Compact

During the London Conference in Syria in February 2016, Jordan proposed a “‘holistic’ approach to manage the ‘spill over’ from the crisis on its economy, by advancing the vision of ‘turning the crisis into a development opportunity’ for Jordan” (Panizzon 2019, 226-227). The meeting resulted in the International Compact for Jordan, co-chaired by Germany, Kuwait, Norway, Qatar and the United Kingdom and the International Monetary Fund/World Bank and Multilateral Development Banks. Through the compact, $700 million grants were made available for the 2016 – 2018 JRPs, plus an additional $300 million in loans for education and job creation, particularly in sectors with a high ratio of foreign workers and with a high degree of skills match (Panizzon 2019). The Compact also enabled a simplification of the rules of origin applicable to Jordanian goods imported into the EU, on the condition that production of said goods involved new job opportunities for Syrians. Combined, the humanitarian aid, development assistance, and trade benefits negotiated as part of the compact outstrip the assistance provided to any other state in the region (Kelberer, 2017), totalling €3.3 billion in through various instruments since 2011 (European Commission 2022). Since the Jordan Compact and the London donor conference in February 2016, there has been an annual Brussels conference (between 2017 and 2021) associated with the EU Trust Fund for Syria. The pledges are tied with the Regional Response Plans mentioned above.

The commitment of granting 200,000 formalised work opportunities for Syrians was widely praised, yet there is a wide chasm between the compacts’ templates, refugees’ perceptions, and countries’ governance dynamics (Lenner and Turner, 2019) and access to work and working conditions through the Jordan Compact have not been an unmitigated success (Barbelet, Hagen-Zanker and Mansour-Ille, 2018; Lenner and Turner, 2019). At the same time, the Egyptians migrant labour force are typically seen to have been the losers in the Compact, rather than Jordanians (Baylouny 2020), and there has been little reflection on the impacts of the Compact on other refugee populations in Jordan.

Encampment

Palestinians camps were established for those fleeing the 1948 and 1967 conflicts. Camps became associated with the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO), serving as spaces for recruitment and an emblem of the struggle. Achilli (2015) argues that in some cases – such as al-Wehdat – Palestinian camps achieved quasi-autonomy from the Jordanian government. Tensions between the Jordanian government and the PLO supported Palestinian Fedayeen (guerrillas) escalated to outright violence in Black September, continuing into 1971, and resulting in wide-spread destruction of al-Wehdat as well as other sites. Today, Palestinian camps continue to be part of the fabric of urban Amman and other key cities and areas of Jordan (UNRWA, 2018), but are seen to be under close surveillance of the Jordanian government (Peteet 2011).

The history of politicisation of Palestinian camps in Jordan, and associated security fears have often been used to explain why Jordan avoided encampment for subsequent refugee populations, including the Iraqis. However, Turner (2015) suggests a greater concern for financial aid and economic conditions – and the related impacts on regime stability – than security as such motivated Jordanian policies towards Syrian encampment. He argues that Jordan’s encampment policies supported its aims to reduce dependence on low-wage foreign labour and to support the employment of Jordanians, and that non-encampment policies were disrupted by the challenges of securing financial support for hosting Iraqi refugees due to their non-encampment – and therefore, their lower visibility to the international community.

At the very beginning of the conflict, Syrian refugees could enter Jordan and live outside of camps, however, camps were quickly established in the north of the country, most prominently Zataari in 2012, followed by Azraq in 2014. In the initial years of Syrian displacement to Jordan, policy towards Syrian refugees largely confined them to camps, although a large proportion of Syrians lived outside of the camps, either under the radar or through the bail-out system. At this time, refugees could only formally leave the camps if ‘bailed out’ by a Jordanian citizen acting as a guarantor (Achilli 2015b). This gave rise to further challenges and risks of exploitation, with many making large payments to ‘middlemen’ to facilitate bailout, and specific concerns related to early marriage as a ‘way out’ of the camps.

Starting in early 2015 the government initiated an urban verification exercise to regularise the status of refugees living outside of the camps through the issuing of new MoI cards (NRC 2016). Current figures estimate that 80% of the refugee population in Jordan resides outside of the camps (UNHCR 2023b). Despite this, the camps continue to play an important role in the refugee response within Jordan, promoting legibility of the refugee population to the international community and allowing refugee populations to be read as an economic burden and security risk (Ali 2021).

Immigration policy

Foreign citizens have limited rights, including exclusions from strikes and union membership. They also have few political rights. However, access to public services, particularly primary health care and basic education are now largely available to migrant populations, albeit with specific restrictions and costs for certain populations.

Entry requirements and visas

Nationals of some countries can enter Jordan without a visa – this is primarily other Arab countries through reciprocity agreements, and with a time limitation on their stay. Citizens of other countries require a visa before entering Jordan (de Bel-Air 2019). Those from the Gulf and most Arab states (not including Sudan, Yemen, or Iraq) and EU nationals can get entry visas at the border (Jordan Embassy in the UK 2022).

Residence

Residency permits are available for those working professionally, with sufficient means of living, with commercial or industrial investments, who have locally unavailable skills, or for studies. These are temporary one-year permits, which are renewable. Arab investors and their families can obtain a 3-year permit, and women married to Jordanian citizens and people living regularly in the country for ten years can obtain a 5-year permit. Arabs and students, among others, are exempted from residence fees. The 2009 Regulation on Egyptian workers’ families to visit allows for the visit of an Egyptian migrant’s wife, ascendants, minor children and unmarried children, in cases where the migrant has a one-year residence permit and sufficient income (350 dinar per month).

Foreign citizens may purchase property, subject to ministerial authorisation and based upon reciprocal agreements with the foreign national’s country of origin. Arab citizens are exempted from reciprocity condition and they can also buy to invest (Law n°24 of 2002).

Labour migration to Jordan

- 1996 labour law is the main legislation managing foreign workers employment in Jordan. This law specifies that labour migrants may only be employed with special authorisation and where the work requires expertise or skills unavailable in the Jordanian workforce, but does not list closed or restricted professions (MoL 1996)

- Decree n°90 of 2000 and 28 of 2002: Specific stay and employment conditions in Qualifying Industrial Zones

- 2005 and 2007 Regulations concerning the employment of foreign workers

- 2008 Law n°48 amending labour law to include domestic and agricultural workers under the provisions of the labour law.

- 2009 By-law n°89 (Foreign Workers Recruitment Regulation) governing the employment of non-Jordanian domestic workers by the private recruitment agencies

Jordan is also party to international agreements governing labour migration, including 20 ILO conventions ratified and a Memorandum of Understanding between Jordan and United Nations Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM) regarding empowering women migrant workers in Asia (2001)

The 1996 Labour Code sets out parameters for the employment of non-Jordanians (Section 12), excluding domestic workers for whom separate regulations apply (MoL 2009), and some agricultural workers, subject to decisions by the Council of Ministers (MoL 1996). Jordan’s approach to labour migration became more protectionist from the 2000s. The periods immediately preceding and following this change saw large scale expulsion of up to 39,000 foreign nationals (MPC 2013; Fargues 2009). Work permit regulations (Regulations No. 36 of 1997) were amended in 2016, with 19 professions closed to non-Jordanians. Limited exceptions apply for non-Jordanians with a Jordanian parent or spouse, workers with companies protected under the Investment Promotion Law, foreign companies working with the government, and those working directly with the government. For some professions, non-Jordanians may be employed in line with a quota, or in consultation with the MoL. Closed professions include: administration and accounting, clerical work, switchboards and telephone, warehouse, sales, decoration works, fuel selling in main cities, electricity, mechanics, drivers, guards and servants, medical professionals, engineers, hairdressers, teaching professions, fruit and vegetable unloading, cleaning in private schools and hotels, and in regional offices based in Jordan below a certain managerial level (MoL 2017). In 2020, this was increased to 28 professions (15 closed, 13 restricted) (Kayed 2020). Only 17% of non-Jordanian workers are estimated to hold a work permit that matches their actual employer and employment occupation (ILO 2017b).

In those sectors open to foreigners, quotas for the maximum proportion of non-Jordanian workers may be established. In physically challenging, unhealthy, or night-shift work, this may reach up to 60–70% of the workforce (de Bel-Air 2019). There remains a significant disparity in the treatment of Jordanian and foreign workers, including in the minimum salary (as of 2016, this stood at JD220/month for Jordanians, JD110 for foreigners). Further, Jordan has 14 Qualifying Industrial Zones (QIZ), with a high proportion of migrant workers – within the apparel industry alone an estimated 75% of the 60,000 workers are migrant workers from South and Southeast Asia (ILO 2017), and the majority are female. Previously, concerns have been raised about exploitative and dangerous conditions within QIZs, including links to trafficking (Al-Wreidat and Rababa 2011). The Government of Jordan has put in place a programme of improvements to improve legal compliance, attain ILO standards, and identify cases of trafficking, and while issues remain, improvements have been seen (ILO 2017).

In addition to the above agreements, there have been a number of specific bilateral agreements regarding labour migration, including with: Bangladesh, Egypt, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia, Nepal, Philippines, Sri Lanka, Tanzania, and Uganda (IOM 2021, ILO 2015, ILO 2021, ILO 2023, Migrant Forum in Asia 2014)

Medical visas

Jordan is considered a leader in the region for medical tourism. This is assisted by specific visa regulations for those from certain countries that allow for a shorter application process or visas on arrival. As of 2018, Sudanese, Libyans, Yemenis, Iraqis, Syrians, Chadians, Ethiopians, and Nigerians were eligible for this process (Ghazal 2018). Those entering on medical visas may be accompanied by a limited number of family members, including children. However, there are concerns that some use the medical visa to secure entry to Jordan, before engaging in work or registering with UNHCR. As noted above, the government of Jordan has responded by requesting UNHCR to halt the registration of asylum seekers entering Jordan on a medical visa.

Border control policy

Visa requirements are discussed above, including the general dispensations for nationals of Arab countries. However, Jordan has often steadily increased restrictions on access and residency for nationals of Arab countries experiencing conflict, including Iraq, Yemen, and Syria.

The 1973 Law 24 governs the removal of those with unauthorised entry or stays in the country (Global Detention Project). Those found to have overstayed their visas, contravened the conditions of their visas, or entered the country through an unofficial border crossing who have not regulated their status may be subject to detention and deportation. Those who are deported are subject to a re-entry ban for at least 5 years. As of 2014, there were 2451 immigration detainees, although data in this area is limited and most migrants are detained under regulations pertaining to labour or other offences, rather than under migration offences per se (Global Detention Project 2020).

Jordan has been criticised by human rights bodies for issuing deportation orders against foreign nationals found to be without correct work and residency documentation, including individuals from Syria (HRW 2017) Yemen (HRW 2021), and Sudan (HRW 2015).

With the COVID-19 pandemic, additional border controls were imposed, including border closures, quarantining, proof of vaccination and PCR testing. At the time of writing, border controls have been eased.

Human trafficking / smuggling policy

Jordan remains a destination for Syrian refugees, in spite of the border closures. However, originally a preferred destination for migrants from south Syria, Jordan has become a less popular destination among young men in Daraa in south Syria due to worsening economic conditions and personal security concerns linked to recent rapprochement towards Syria (Al-Jabassini 2022).

The kafala system was highlighted as high risk (Tamkeen 2021) particularly in relation to migration from East and South-East Asia. There is also some evidence of migrants travelling from the Horn of Africa to Jordan via Yemen and Saudi Arabia. In other cases, domestic workers in Jordan have reported issues with women being trafficked from Jordan to Gulf countries. A 2009 Law n°9 on Prevention of Trafficking in Persons penalises those who commit human trafficking with imprisonment or a fine. Failing to alert the authorities to trafficking is also penalised with up to 6 months imprisonment. The law also contains provisions to facilitate the return of victims to their home country or other countries, and housing those affected in facilities providing appropriate support (MPC 2013; Tamkeen 2015). However, despite the presence of specific legislation, in 2018 the US State Department classified Jordan as a Tier 2 country. Tier 2 status indicates that a country has yet to fully implement all necessary measures, but are making efforts to do so.

Emigration and diaspora policy

Jordanian citizens have the freedom to stay abroad and to claim additional citizenships (1954 Law n° 6 on Nationality). Those who have residence in Jordan maintain the right to participate in local and general elections, and access to Social Security (law n°30 of 1978) (MPC 2013)

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs holds responsibility for relationships with Jordan’s expatriates, however there is also an active array of Jordanian organisations, associations, professional and student networks aimed at providing specialist services to Jordanians working and living abroad, and creating links between them (MPC 2013). Jordan Strategy Forum, an association of private companies, academics and economists, released a report in 2017 highlighting the value of remittances to the Jordanian economy and suggesting measures for further increasing remittance flows (Jordan Strategy Forum 2017). As yet, there is limited overarching clarity, but there does appear to be some momentum among business, civil society, and the Jordanian government to enhance diaspora engagement, particularly pertaining to business investment.

Return and readmission policy

The 2014 EU-Jordan mobility partnership contains provisions for the negotiation of a readmissions agreement, alongside an agreement facilitating the issuing of visas (European Commission 2014). The mandate to negotiate has existed since 2015 (European Court of Auditors 2021), and negotiations were launched in 2016, but have made little significant progress. In 2020, 440 individuals were returned from the EU-27 to Jordan, down from 520 in 2019, with the majority being returned from Germany (Eurostat, consulted August 2022).

Part II: International migration policy relations

Introduction

The international migration policy relations must be understood at the interface between Middle East geopolitical relations and global geopolitics, including the relationship with European migration policy and the role of international aid in influencing some of those wider relations. In the geopolitical context of the Middle East, Jordan is often mentioned as a stability element in the region. In its relationship to Europe, Jordan is considered a containment state for refugees with a potential to move towards Europe. In its self-presentation, it is a transit state where migrants and refugees are considered as temporarily present.

Two interlinked elements may help to understand the international migration policy relations vis-à-vis the EU and other international organisations and bodies: financial aid and securitisation. It is in the interest of the international community, dominated by northern states, that Jordan continues to be willing to host refugees on their territory. Jordan uses this interest in its negotiation with the EU, taking an active role as negotiator in the aid flows and policy, lobbying for increased aid and threatening to withdraw services and protections (Kelberer 2017, p 153). Seeberg (2020, pg. 3) describes this as ‘migration diplomacy.’ In this context, Jordan is often described as a ‘rentier state’: a state seeking “to leverage their position as host states of displaced communities for material gain” (Tsourapas 2019a, pg. 465).

These claims are buttressed by a discourse that positions refugees as an economic burden and a security threat, an exclusionist discourse that both the EU and Jordan seem to accept (Pasha 2021). The understanding of security in the Jordanian context is wide-ranging, relating not only to imminent threats, but also ‘non-traditional’ (pg. 1144) concerns: political stability, population balance between refugees and nationals, maintenance of natural resources (especially water), safeguarding the economy, maintaining social cohesion, and protecting outer territorial borders.

This positioning of refugees as a risk has informed the development of a shared discourse of resilience between the EU and Jordan. For the EU, resilience thinking is centred on the humanitarian-development nexus, the responsibility of crisis-affected states, and framing refugees as an economic development opportunity for refugee-hosting states” (Anholt and Sinatti 2020: 312). For Jordan, this is evident in their emphasis on assistance as benefitting the whole society and not only targeting refugees, and their active role in managing the response. Anholt and Sinatti (2020) argue that the EU’s resilience-building in Jordan is a refugee-containment strategy, based on underlying assumptions that the economic integration of refugees will prevent onwards movement and support the host country’s development. Although less explicit than some of the externalisation processes witnessed in other countries, the EU’s actions nonetheless serve to constrain movement and export the management of migrating populations beyond Europe’s territorial borders. Baylouny (2020) interrogates some of the claims regarding the impact of Syrian refugees on the Jordanian population, and subsequent effects on the stability of the governing powers, as do Fakih and Ibrahim (2016), who find no connection between the Syrian influx and the Jordanian labour market. However, as Jordan continues to experience economic crisis, high levels of unemployment, and regional insecurity, a number of commenters have questioned the appropriateness and long-term relevance of a resilience-based framework, and the risk that such an approach poses to Jordan and Europe and, ultimately, refugees themselves (Anholt and Sinatti 2020, Achilli 2015).

Regional policy context

In this section, we situate Jordan in both a global and regional policy context.

The US and Gulf countries, particularly Saudi Arabia, are significant actors in Jordan with long histories of economic support and alignment on key regional and international issues (Muasher 2020). As noted above, Jordan’s migration landscape cannot be understood separately from historical and current bilateral and regional relationships with Palestine and Israel, which are in part shaped by the priorities of external actors, including the US (Pasha 2021). Another key relationship in understanding the current state of EU-Jordan interaction is the relationship to Egypt and Jordan’s use of Egyptian labour migrants. To large extent, Egyptian labourers are the population who have been most at risk and most affected by the inclusion of the Syrian refugees into the labour force. Jordan’s securitisation approach must also be seen in relation to Egypt in this context (see Tsourapas and Verduijn 2018). The particularities of Jordan’s relationship with refugee-origin countries has also, to some extent, shaped refugees’ reception in Jordan (Chatelard 2002; Mason 2011; Seeley 2010).

The EU has played a significant role in assistance to Jordan, mainly towards the Syrian refugee crisis, alongside UN bodies, the ILO, IOM, and in addition to assistance and loans from global financing mechanisms, A general trend is that UNHCR and other multilateral aid agencies and major donors have increased their presence in the country over the past two decades and more of the assistance is now channelled directly to the state (Kelberer 2017). This strategy is closely related to the fact that the international community relies on Jordan to continue containing refugees within their territory, with support operating as an indirect externalisation process. The shift towards a more active fundraising strategy by the Jordanian state may be a direct consequence of the history of hosting Iraqis: with less international funding, and more focus on Iraqis as a security threat, the willingness to host refugees was significantly reduced from 2006. Jordan is seen as the stable country in the region and this geopolitical stability is also used by the international community as an important argument in the nature of assistance to the country.

There seems to be a point in history at which Jordan’s attitude towards international aid changed from not being willing to accept international aid for assisting refugees to using international aid actively in their migration diplomacy. It is particularly the present stage in which aid has become an essential dimension of the EU-Jordan relations that we are interested in here.

Europe-Jordan relations and migration policies

Jordan is considered as part of the EU’s ‘immediate neighbourhood’, despite not sharing a common border or direct sea route. For those with access to passports and visas, there are multiple direct flights to European destinations each day. Others travel by air to Turkey and on to Europe from Turkey (Achilli 2016). Fewer travel overland from Jordan to Turkey. Yet others travel south, through Egypt and on to countries bordering the Mediterranean (Al-Jabassini 2022). In terms of migration, for the EU, Jordan is more relevant as a transit country for refugees than as an emigration country, hence refugees constitute a core dimension of the Europe-Jordan migration policies. In this context, Jordan uses migration diplomacy as a strategy for its relationship to the EU (Seeberg 2020). At the same time, the EU has consolidated its strategic position in the region (Fakhoury 2019). This can be seen in firstly through the EU’s participation in broader regional refugee processes, including the incorporation of its funding instruments, such as the Regional Trust Fund in Response to the Syrian Crisis (Madad), into the Regional Refugee and Resilience Plan (3RP), and secondly in the development of the EU’s own relationships and agreements with Jordan (Fakhoury 2019). Previously, the EU’s 2005 Global Approach to Migration (GAM) did not have clear approach with regards to MENA, but the last decade has seen the negotiation of the 2014 Mobility Partnership and the 2016 Jordan Compact, consolidating Jordan’s status in the European Neighbourhood Policy (Fakhoury 2019).

We have looked at the following EU-Jordan agreements:

EU-Jordan Association Agreement (1997, in force 2002)

The Association Agreement replaced an earlier cooperation agreement (signed 1977, in force from 1978). Its core objectives include: providing a framework for political dialogue; establishing conditions for liberalisation of trade in goods, services, and capital; developing balanced economic and social relations; improving living and employment conditions for productivity and financial stability; encouraging regional cooperation to consolidate peaceful co-existence and economic and political stability; and promoting cooperation in areas of reciprocal interest. Within this, the association commitments on social and cultural aspects includes establishing dialogue on illegal immigration and the conditions for the repatriation of illegal immigrants, as well as actions regarding the reintegration of repatriated illegal immigrants (MPC 2013). The agreement aimed at a Free Trade area between both sides, which was established in 2014. Jordan-EU trade relations and their connection to migration policy are discussed further below, with regards to the Jordan Compact.

EU Neighbourhood Policy (ENP) (2004)

The ENP was launched in 2004 to foster stability, security, and prosperity in Europe’s neighbouring countries. It contains three priority areas for cooperation: Economic development for stabilisation, security, and migration and mobility. In 2005, Jordan adopted its first European Neighbourhood Policy Action Plan (European Commission 2009). Since then, the cooperation between Jordan and the EU has been based on gradually closer and more complex agreements, not least following the worsening of the Syrian crisis from 2011. This includes the 2014 Mobility Partnership and the 2016 Jordan Compact, discussed in greater detail below.

In 2021, the European Commission launched the new Agenda for the Mediterranean, along with an Economic and Investment Plan for Southern Neighbours (European Commission 2022). The 14th EU-Jordan Association Council was held in June 2022, with partnership priorities adopted that will guide the partnership until 2027. June 2022 also saw the launch of the EU Jordan Investment Platform, seeking to catalyse private and public investments in Jordan (Jordan Times 2022). Between 2014 and 2020, the European Neighbourhood Instrument was the primary EU financial tool in Jordan. For the period 2021 – 2027, this has been replaced by the new Neighbourhood, Development and International Cooperation Instrument (NDICI). €364 million have been allocated as part of the Multi Annual Indicative Programme for this initial period (2021-2024), focusing on three areas: good governance; green transition and a resilient economy; and support for human development (European Commission 2022).

EU-Jordan Mobility Partnership (2014)

The EU-Jordan dialogue on Migration, Mobility and Security was launched in December 2012 (European Parliament 2014) and resulted in the Mobility Partnership between Jordan and EU in 2014 (European Parliament 2014). The mobility partnership between Jordan and the EU (European Parliament 2014, 2014a) addresses both Jordanians migrating to and living in the EU and Jordan as a major refugee hosting country. The Mobility Partnership contains four key objectives: effective management of mobility for short periods, legal, and labour migration; strengthening cooperation on migration and development, and the positive potential for migration for the development of signatories – including negotiations on facilitating procedures for Jordanian citizens to receive Schengen visas; combatting irregular migration, trafficking, and smuggling and promoting and effective return and readmission policy; and strengthening the capacity to manage refugees in line with international standards (European Parliament 2014).

Jordan Compact (2016)

The Jordan Compact of 2016 represents one of the key moments in the relationship between EU and Jordan and has had wider ramifications in terms of global migration governance. The Compact can be seen as part of the externalisation of asylum with compensation in terms of trade preferences and development aid in return for containment of refugees (Panizzon 2019). The Compact follows the agreement between the EU and Jordan on a Moblity Partnership, in which a broad understanding of security forms an important basis (Seeberg and Zardo 2020). The compact’s overall logic draws on trade as migration policy and must be understood as an instrument for refugee employment and as such contributes to what Tsourapas (2019) terms ‘refugee commodification’. Such moves towards access to work fit with the EU’s ‘resilience’ building approach, however, with worsening economic conditions and increasing unemployment, frustrations are growing among Jordanians and refugees alike, with people – particularly the young and educated – looking to leave.

Part III: Concluding remarks

Migration policy in Jordan often appears reactive, constituted within an emergency response framing despite the protracted time frame of displacement for all refugee populations in the country. It also demonstrates a bifurcated approach, with little relationship between labour migration and refugee protection, despite a flagship refugee policy focused on access to the labour market for Syrian refugees. Further, within the refugee response, there is a stark distinction between the protections and services available to different nationalities of refugees. These responses are driven by the historical and current political and social relationships between Jordan and refugees’ countries of origin, the availability and orientation of external funding, and Jordan’s internal security concerns and dynamics. The language of security permeates the refugee discourse in Jordan and, while external actors have been keen to address and downplay the risk of social tensions between refugees and Jordanian citizens, there is little challenge to the discourse of refugees as an economic burden. This security focus therefore permeates the relationship between Jordan and the EU.

In general, Jordan and the EU profess strong relationships and a large degree of coherence between their migration policy objectives. While their priorities may differ, there is a high degree of cooperation between the two partners, and they have constructed a partnership that, on the face of it, works for them. Their migration diplomacy must be seen in the context of the prominent discourse on resilience in refugee response work, and its intersections with financialisaton and contextually-specific understandings of security. Both Jordan and the EU appear to have embraced a resilience framework in shaping their relationship, despite legitimate and persistent concerns about the reality of resilience-building in Jordan, the exacerbation of structural challenges, and increasing public dissatisfaction at the impact of such policies on migrants and Jordanians (Anholt and Sinatti 2020).

In addition to the emphasis on the need for financial support and their strategic role in regional stability, Jordan’s migration diplomacy has also worked to shape EU external governance (Fakhoury 2019). For example, the EU has continued to support Jordan, despite governance constraints (Fakhory 2019, Seeberg 2016, Anholt and Sinatti 2020), disregard of core policy positions, and sometimes slack refugee governance (e.g. closing borders). Jordan has also sometimes dismissed refugee-related instruments after their adoption, or ensured, despite initial rhetorical compliance, that the implementation of such instruments follows their own priorities and approaches. For example, despite the development-oriented nature of the Compact, Jordan has not formally moved away from a guest-approach, structural constraints relating to access to employment have not changed, and easing permits for Syrian refugees has not resulted in the reform of Jordan’s asylum system. By and large, refugee-related agreements are only implemented so far as they do not stir Jordanian and migrant dissent or upset business leaders.

The EU and Jordan are both astute international players, adept in leveraging positions to meet their needs and find common face-saving ground. Yet neither actor is the strongest in the region – the EU is dwarfed by the US and regional powers. Similarly, Jordan is primarily valuable to the EU as a mediator of other concerns, rather than its own demands. Humanitarian assistance levels are falling, as attention shifts to newer crises, and particularly the Ukraine conflict. Resilience-based approaches are showing their limits in responding to long-term displacement in contexts where refugees cannot access full rights, and where economic conditions are worsening. As attention shifts, the Syrian conflict continues, and few refugees envisage return as possible. While the international community continues to profess the value of the humanitarian-development nexus, there is limited clarity as to what this development would entail in Jordan in particular, and refugees’ place within it. Alongside displacement, Jordan is also contending with worsening environmental concerns, particularly water scarcity (Achilli 2016, Pasha 2021). The partnership between Jordan and the EU has made new strides in the response to refugees. However, these approaches are showing their limits: for the protection of refugees, for Jordan, and for the EU. It seems likely that the partnership will continue to evolve, but as it does so refugees, migrants, and Jordanians must not be left behind.

References

3RP (2021). Regional Refugee and Resilience Plan in Response to the Syria Crisis. Available at: https://www.3rpsyriacrisis.org/ Last accessed 16/09/2022

Achilli L. (2016). Tariq al-Euroba displacement trends of Syrian asylum seekers to the EU. https://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/38969/MPCRR_2016_01.pdf

Achilli (2015) Al-Wihdat Refugee Camp: Between inclusion and exclusion. Jadaliyya 12 February 2015. Available at: https://www.jadaliyya.com/Details/31776

Achilli (2015b) Syrian Refugees in Jordan: A Reality Check. Migration Policy Centre, European University Institute. Available at: https://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/34904/MPC_2015-02_PB.pdf

Ali, A. (2021) ‘Disaggregating Jordan’s Syrian refugee response: The “Many Hands” of the Jordanian state’, Mediterranean Politics, 00(00), pp. 1–24. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13629395.2021.1922969.

Al-Jabassini (2022) Migration from Post-War Southern Syria: Drivers, Routes, and Destinations. Middle East Directions Programme (MED), part of the Robert Schuman Centre, EUI. Research Project Report Wartime and Post-Conflict in Syria Issue 2022/01 – 06 January 2022. Available at: https://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/73592/QM-05-21-370-EN-N.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

Almasri (2021) The Political Economy of Nationality-Based Labor Inclusion Strategies: A Case Study of the Jordan Compact, Middle East Critique, 30:2, 185-203

Arar, R. (2017) ‘Leveraging Soverignty: The Case of Jordan and the International Refugee Regime’, in M. Lynch and L. Brand (eds) POMEPS Studies: Refugees and Migration Movements in the Middle East, pp. 12–15. Available at: https://pomeps.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/POMEPS_Studies_25_Refugees_Web.pdf.

Al-Wreidat, A. and Rababa, A. (2011) Working Conditions for Migrant Workers in the Qualifying Industrial Zones of The Hashemite kingdom of Jordan. CARIM Research Report; 2011/10; [Migration Policy Centre]; [CARIM-South], European University Institute. Available at: https://cadmus.eui.eu/handle/1814/19884

Anholt and Sinatti (2020) Under the guise of resilience: The EU approach to migration and forced displacement in Jordan and Lebanon, Contemporary Security Policy, 41:2, 311-335

Arab Barometer (2022) Arab Barometer VII: Jordan Report. Available at: https://www.arabbarometer.org/wp-content/uploads/ABVII_Jordan_Report-EN.pdf Last Accessed 6th January 2023.

Barbelet, V., Hagen-Zanker, J., Mansour-Ille, D. (2018) The Jordan Compact: Lessons learnt and implications for future refugee compacts. ODI Policy Briefing

Baylouny, A.M. (2020) When Blame Backfires: Syrian Refugees and Citizen Grievances in Jordan and Lebanon. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Canefe 2016 States of Exile: Rethinking Forced Migration in Contemporary Middle East, https://www.academia.edu/33435814/States_of_Exile_Rethinking_Forced_Migration_in_Contemporary_Middle_East

Chatelard, G. (2002) ‘Jordan as a transit country: semi-protectionist immigration policies and their effects on Iraqi forced migrants’, New issues in refugee research, (61), p. 42.

Chatty, D. (2010) Displacement and Dispossession in the Middle East. Cambridge University Press.

Muasher 2020 Jordan: Fallout From the End of an Oil Era. Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. Available at: https://carnegieendowment.org/2020/06/09/jordan-fallout-from-end-of-oil-era-pub-82008

Chatelard (2002) Jordan as a transit country: semi-protectionist immigration policies and their effects on Iraqi forced migrants. New Issues in Refugee Research. Working paper No. 61. Available at: https://www.unhcr.org/uk/research/working/3d57aa757/jordan-transit-country-semi-protectionist-immigration-policies-and-effects.html

Clutterbuck, Hussein, Mansour, and Rispo (2021). Alternative protection in Jordan and Lebanon: the role of legal aid. Forced Migration Review, 67.

Davis, Benton, Todman and Murphy (2017) Hosting guests, creating citizens: Models of refugee administration in Jordan and Egypt Refugee Survey Quarterly, 36:2

de Bel-Air (2019) The Foreign Workers in The Palgrave Book of Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. Ed. P.R. Kumaraswamy. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan. 49-68

De Bel-Air (2016) Migration Profile: Jordan. Migration Policy Centre, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies, European University Institute, Florence. 2016:06

Diaspora for Development (2020). Diaspora Engagement Mapping: Jordan. Diaspora for Development. Available at: https://diasporafordevelopment.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/CF_Jordan-v.2.pdf Last accessed 16/09/2022

Directorate-General for Neighbourhood and Enlargement Negotiations (2021) ‘Joint Declaration between the European Union and the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) on European Union support to UNRWA (2021-2024)’.

DPA (2022) Department of Palestinian Affairs. Available at: http://www.dpa.gov.jo/Default/Ar Last Accessed 16/09/2022

Edwards and al-Homsi (2020) Jordan returns refugees to desolate Syrian border camp, rights groups cry foul. The New Humanitarian. Available at: https://www.thenewhumanitarian.org/news-feature/2020/09/16/Jordan-expels-syrians-rukban-refugee-camp Last Accessed 6th January 2023.

El-Abed (2014). The Discourse of Guesthood: Forced Migrants in Jordan, in Managing Muslim Mobilities. Between Spiritual Geographies and the Global Security Regime Eds. Anita Fabos and Riina Isotalo. Palgrave Macmillan 81 – 100

El-Abed (2006). Immobile Palestinians: ongoing plight of Gazans in Jordan Forced Migration Review, 26. 17–18

European Commission (2022). European Neighbourhood Policy and Enlargement Negotiations: Jordan. Available at: https://neighbourhood-enlargement.ec.europa.eu/european-neighbourhood-policy/countries-region/jordan_en Last Accessed 16/09/2022

European Commission (2020) Erasmus+ for higher education in Jordan. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/assets/eac/erasmus-plus/factsheets/neighbourhood/jordan_erasmusplus_2019.pdf Last accessed 27th September 2022

European Commission (2018) Responding to the Syrian Crisis: EU Support to Resilience in Jordan

European Commission (2014). EU-Jordan: a new partnership to better manage mobility and migration. Press Release 9th October 2014. Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_14_1109 Last Accessed 16/09/2022

European Commission (2009). Implementation of the European Neighbourhood Policy in 2008: Progress Report Jordan. Commission staff working document accompanying the communication from the commission to the European Parliament and the council. Commission of the european communities. Brussels, 23/04/09 sec(2009) 517/2. Available at: https://www.ecoi.net/en/file/local/1148570/1228_1241445618_jordanien.pdf

European Court of Auditors (2021) Special Report EU readmission cooperation with third countries: relevant actions yielded limited results. European Court of Auditors. Available at: https://www.eca.europa.eu/Lists/ECADocuments/SR21_17/SR_Readmission-cooperation_EN.pdf

European Parliament (2014) Joint declaration establishing a Mobility Partnership between the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan and the European Union and its participating Member States. Available at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/cmsdata/124061/20141009_joint_declaration_establishing_the_eu-jordan_mobility_partnership_en.pdf

Eurostat (2022). Data Explorer. Available at: https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/submitViewTableAction.do consulted August 2022

ElDidi, van Biljon, Alvi, Ringler, Ratna, Abdulrahim, Kilby, Wu and Choudhury (2022) Reducing vulnerability to forced labour and trafficking of women migrant workers from South- to West-Asia. Development in Practice. SI: Modern Slavery and Exploitative Work Regimes. Online

Fakhoury, T. (2019) The European Union and Arab Refugee Hosting States: Frictional Encounters. Centre for European Integration Research. Working Paper No. 01/2019.

Fakih and Ibrahim (2016) The impact of Syrian refugees on the labor market in neighboring countries: empirical evidence from Jordan, Defence and Peace Economics, 27:1 64–86

Fargues (2009) Work, Refuge, Transit: An Emerging Pattern of Irregular Immigration South and East of the Mediterranean, International Migration Review, Volume 43 Number 3 (Fall 2009):544–577

Frangieh (2016) Relations Between UNHCR and Arab Governments: Memoranda of Understanding in Lebanon and Jordan, The Long-Term Challenges of Forced Migration Perspectives from Lebanon, Jordan and Iraq. LSE Middle East Centre Collected Papers | Volume 6, 37-43

Global Detention Project (2020), Jordan Overview. Global Detention Project. Available at: https://www.globaldetentionproject.org/countries/middle-east/jordan

HRW 2021) Jordan: Yemeni Asylum Seekers Deported, Others Face Deportation Decisions. Human Rights Watch. March 30, 2021 Available at: https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/03/30/jordan-yemeni-asylum-seekers-deported

HRW (2020) Jordan: Events of 2019. Human Rights Watch. Available at: https://www.hrw.org/world-report/2020/country-chapters/jordan

HRW (2017) “I Have No Idea Why They Sent Us Back” Jordanian Deportations and Expulsions of Syrian Refugees. Human Rights Watch, October 2017.

HRW (2015) Jordan: Deporting Sudanese Asylum Seekers, Police Take 800 From Protest Camp to Airport. Human Rights Watch. December 16 2015. Available at: https://www.hrw.org/news/2015/12/16/jordan-deporting-sudanese-asylum-seekers

HRW (2006) “The Silent Treatment”: Fleeing Iraq, Surviving in Jordan. Available at: https://www.hrw.org/reports/2006/jordan1106/4.htm Last Accessed 6th January 2023

Humanitarian Foresight Think Tank (2017) Jordan and the Berm Rukban and Hadalat 2017 – 2018 Available at: https://www.iris-france.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/Sensitive-Jordan-and-the-Berm-1.pdf Last Accessed: 6th January 2023

ILO (2023) Bilateral labour arrangements (BLAs) on labour migration. Available at: https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/labour-migration/policy-areas/measuring-impact/agreements/lang--en/index.htm Last Accessed 01/03/2023

ILO (2022) Jordan and ILO sign agreement to support the extension of social security coverage and promote formalization. International Labour Organisation. Press release 24th May 2022. Available at: https://www.ilo.org/beirut/media-centre/news/WCMS_846298/lang--en/index.htm Last accessed: 23rd September 2022

ILO (2021) Training manual on the ILO Guidelines for skills modules in bilateral labour migration agreements. International Labour Organisation. Available at: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---protrav/---migrant/documents/publication/wcms_778029.pdf

ILO (2017) Migrant domestic and garment workers in Jordan: A baseline analysis of trafficking in persons and related laws and policies / International Labour Office, Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work Branch (FUNDAMENTALS) – Geneva: ILO, 2017.

ILO (2017b) A challenging market becomes more challenging: Jordanian Workers, Migrant Workers and Refugees in the Jordanian Labour Market. International Labour Organisation. Available at: https://www.ilo.org/beirut/publications/WCMS_556931/lang--en/index.htm Last accessed 26th September 2022

ILO (2015) Bilateral Agreements and Memoranda of Understanding on Migration of Low Skilled Workers: A Review https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---protrav/---migrant/documents/publication/wcms_385582.pdf

IOM (2021) Rapid Assessment of the Southern Corridor (Ethiopia – Kenya – Tanzania – South Africa) IOM/UN Migration Regional Office for East and Horn of Africa and Southern Africa. Available at: https://eastandhornofafrica.iom.int/sites/g/files/tmzbdl701/files/documents/blmas-rapid-assessment-southern-corridor-2021.pdf

Stave, E.S., Kebede, T.A., and Khattaa, M. (2021) Impact of work permits on decent work for Syrians in Jordan. International Labour Organisation. Available at: https://reliefweb.int/report/jordan/impact-work-permits-decent-work-syrians-jordan-september-2021-enar

Jones, K., Ksaifi, L., and Clark, C. (2022) ‘The Biggest Problem We Are Facing Is the Running Away Problem’: Recruitment and the Paradox of Facilitating the Mobility of Immobile Workers’ Work, Employment and Society.

Johnston, R., Baslan, D. and Kvittingen, A. (2019) Realizing the rights of asylum seekers and refugees in Jordan from countries other than Syria, with a focus on Yemenis and Sudanese. Available at: https://reliefweb.int/report/jordan/realizing-rights-asylum-seekers-and-refugees-jordan-countries-other-syria-focus.