Norwegian development assistance in support of social safety nets

1. Mapping of Norwegian ODA in support of social safety nets

1.1 Norwegian support of social safety nets within core ODA sectors

Emergency food assistance (DAC 720.40)

Household food security (DAC 430.72)

Social protection (DAC 160.10)

Conclusions regarding direct ODA to social safety nets

1.2 Imputed aid via multilateral organizations

Conclusions regarding imputed ODA to social safety nets

2. Classification of Norwegian ODA in support of social safety nets

2.1 Emergency vs long-term assistance

2.2 Targeted or universal programs

2.3 Conditional versus unconditional transfers

Conditional vs unconditional transfers

Cash transfers and long-term development

How to cite this publication:

Magnus Hatlebakk (2021). Norwegian development assistance in support of social safety nets. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI Report R 2021:4)

This report is commissioned by Norad as a mapping of Norwegian development assistance in support of social safety nets. It was found that a large share of the support comes in the form of emergency aid via the World Food Program. There has been a transition over time towards more cash transfers, and thus a need for digital solutions in terms of individual accounts and potentially a need for integration with government registers. The mapping was followed by a discussion of selected research findings that may have relevance for the design of Norwegian assistance to safety nets:

1) The choice between conditional and unconditional transfers should depend on the aim of the program. If the aim is to relax liquidity constraints, or help people in need, then unconditional transfers is the right choice, but if the aim is also to incentivize people to send their children to school, or utilize health services, then well-designed conditional transfers will be in place.

2) In remote areas there may be village level poverty traps where the extreme poor meet multiple constraints, and a combination of interventions is necessary to lift them out of poverty in terms of so-called cash-plus, or multifaceted, development programs.

3) A cash transfer will only have an impact on girls’ welfare, beyond the effect via increased household income, if it strengthens the female bargaining position within the household. A cash transfer alone may not be sufficient, and the transfers may have to be combined with other policy instruments, such as programs to strengthen female political participation, self-help groups, entrepreneurship programs, female quotas in hiring processes, information campaigns, inheritance rights, and the right to divorce.

Preface

This report is commissioned by Norad, the Norwegian development cooperation agency, in response to their need for a mapping of Norwegian Official Development Assistance (ODA) in support of social safety nets. The mapping was commissioned to cover relevant DAC-codes, including core support to multilateral organizations, and to have three parts: 1) Mapping of Norwegian ODA for the years 2015–2019 to identify the channels used. 2) Classification of the support by type of support (targeted/universal, conditional/unconditional). 3) Identification of knowledge gaps. In the third part the report focuses on selected knowledge gaps identified in a previous report by Norad on social safety nets published in November 2020. The report is an independent product that represent the analysis and views of the author, and not Norad.

Magnus Hatlebakk

CMI, Bergen, August 2021

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Cindy Patricia Quijada Robles and Espen Villanger for useful comments.

Summary

This report is commissioned by Norad as a mapping of Norwegian development assistance in support of social safety nets. It was found that a large share of the support comes in the form of emergency aid via the World Food Program. There has been a transition over time towards more cash transfers, and thus a need for digital solutions in terms of individual accounts and potentially a need for integration with government registers. The mapping was followed by a discussion of selected research findings that may have relevance for the design of Norwegian assistance to safety nets: 1) The choice between conditional and unconditional transfers should depend on the aim of the program. If the aim is to relax liquidity constraints, or help people in need, then unconditional transfers is the right choice, but if the aim is also to incentivize people to send their children to school, or utilize health services, then well-designed conditional transfers will be in place. 2) In remote areas there may be village level poverty traps where the extreme poor meet multiple constraints, and a combination of interventions is necessary to lift them out of poverty in terms of so-called cash-plus, or multifaceted, development programs. 3) A cash transfer will only have an impact on girls’ welfare, beyond the effect via increased household income, if it strengthens the female bargaining position within the household. A cash transfer alone may not be sufficient, and the transfers may have to be combined with other policy instruments, such as programs to strengthen female political participation, self-help groups, entrepreneurship programs, female quotas in hiring processes, information campaigns, inheritance rights, and the right to divorce.

Introduction

We first report on the actual disbursements of Norwegian official development assistance (ODA) to programs that have a social safety net component. This is not straightforward as these projects are found under different DAC codes (sectors) in the official statistics. We have identified the main DAC sectors, and report all aid to these sectors in combination with short discussions of the most relevant projects within each sector. In the second section we discuss how the Norwegian support fit in with the standard classification of social safety nets, that is, conditional/unconditional, cash vs in-kind, emergency vs long-term, and targeted vs universal transfers. We shall see that emergency assistance is the main category of Norwegian aid to social safety nets. The third section will attempt to map knowledge gaps regarding the impacts of programs in support of social safety nets. The literature is by now extensive, including numerous reviews, thus the focus will be on issues that we believe are important for Norwegian assistance, based on the mapping in sections one and two. The focus will be on how conflicting research findings may be explained by variation in context and type of program and maybe more importantly variation in research questions and research design.

1. Mapping of Norwegian ODA in support of social safety nets

In the mapping of Norwegian support, we apply the World Bank definition of social safety net programs:

Cash transfers and last resort programs, noncontributory social pensions, other cash transfers programs, conditional cash transfers, in-kind food transfers (food stamps and vouchers, food rations, supplementary feeding, and emergency food distribution), school feeding, other social assistance programs (housing allowances, scholarships, fee waivers, health subsidies, and other social assistance) and public works programs (cash for work and food for work).

With the focus on transfers to households this excludes other programs that provide safety for the poor, such as insurance, credit, health, education, infrastructure and employment generating programs, except when these programs have a transfer component, such as cash or food for work programs.

In many ways direct transfers to households reflect a development strategy that is yet to take hold in Norwegian development cooperation. We shall see below that transfers are used primarily in emergency situations (note that emergency aid is included in the definition above). Still, we shall see that the support is regularly part of broader development programs that can, potentially with some changes, contribute to long-term development. We will discuss the potential trade-offs, or synergies, between emergency aid and long-term development to a larger extent in the third section.

To identify relevant DAC-sectors we searched and looked through the Norwegian aid statistics, and identified the relevant DAC-codes as:

DAC 112.50: School feeding

DAC 160.10: Social protection

DAC 430.72: Household food security programs

DAC 720.40: Emergency food assistance

DAC 910: Administration costs/multilateral

DAC 910 will be discussed in section 1.2, while section 1.1 discusses the four other core sectors. In addition to these, DAC 520.10 (food assistance) is in theory relevant, but we found only small amounts in support of staff working for the World Food Programme (WFP). DAC-160.20 (employment creation) includes some cash for work programs, but they constitute only a small share of the total disbursements within this DAC sector, as the focus is on job creation: We find NOK 45 million disbursed over two years to a UNDP led cash for work program on the Gaza strip, while the large sums are for skill development and job creation, with ILO as the main partner (NOK 405 million out of NOK 747 million to DAC.160.20-employment creation over the last six years). DAC 720.10 (material relief assistance and services) is a large sector for Norwegian ODA (NOK 2.5 to 3 billion per year), but the largest disbursements are for humanitarian support in Syria, and based on the project descriptions it appears that relatively small amounts are transfers to households, so we also exclude this DAC sector from the tables below. DAC 430.10 (other multisector aid) includes some very large multi-donor funds that have some smaller social safety net components. It will give a biased representation to include these large sums in the tables below, as most of the funds will not be for social safety net programs. The two largest ones are the Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund (NOK 270 million in 2020), and the World Bank multipartner Fund for Somalia (NOK 142 million in 2020).

1.1 Norwegian support of social safety nets within core ODA sectors

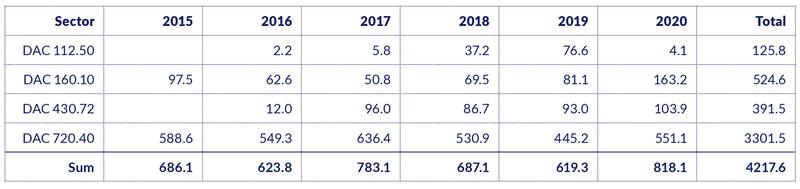

As discussed above, we have identified four sectors where many projects have components that can be considered as support to social safety nets according to the World Bank definition discussed above. We summarize the total amounts disbursed to these DAC sectors in Table 1.1, while keeping in mind that not all projects will have components in support of social safety nets, and if they have such components, then the share of the budget actually being used for transfers to households may be small. It is beyond the scope of this report to go into project documents to classify each and every project. When feasible, based on the description in the aid statistics and with reference to easily available online information on the projects, we will discuss whether the largest disbursements have social safety net components.

Emergency food assistance (DAC 720.40)

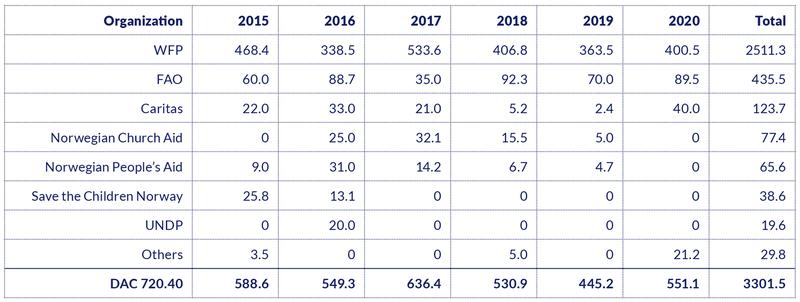

As we can see from Table 1.1 the largest sums go to emergency food assistance. Table 1.2 shows the detailed disbursements to different partners, with WFP as the main partner (NOK 2.5 billion, that is, 76% of the NOK 3.3 billion were allocated through WFP). Most of this (NOK 1.5 billion), in turn, goes to the Middle-East (mainly Syria, Yemen, Lebanon and Jordan).

Other partners are small in comparison, with the Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) (NOK 435.5 million in total over the six-years period) and Caritas (NOK 123.7 million over the six-years period) as the largest. As much as NOK 401 million (92%) of the disbursements via FAO goes to their Emergency Livelihood Response Program in South-Sudan. The program gives direct support to households, but primarily in terms of inputs (mostly seeds) to food production, there is, however, a small food voucher scheme as well. At a general level, FAO states that cash and vouchers are their preferred method of assistance, as it enables recipients to make their own choices. Caritas’s emergency food assistance is focusing on land-locked African countries in conflict (the largest disbursements go to Central African Republic, Niger and South-Sudan). Turning to the largest partner within emergency food assistance, WFP, Table 1.3 reports on the disbursements by country.

We note that there was a very large (NOK 235 million) disbursement to the Syria conflict in 2015. There is not much information to be found on the program components, but it appears to be part of the Syria Response Plan, which in turn seems to include food-rations as one of its components. The emergency food assistance to Syria has continued, and in 2020 includes school lunches and food assistance to vulnerable groups. The other large recipients of Norwegian emergency food assistance via the WFP are Syria’s neighbors Lebanon and Jordan, as well as Yemen and South-Sudan. These are all part of the same large agreement with the WFP. The description of program components varies between countries, in Yemen, for example, the WFP support includes food assistance in kind and as vouchers, plus cash transfers in area where food markets are expected to work well. In general the WFP is deliberately shifting towards more cash transfers in their food assistance, and at an even more general level, the WFP has a deliberate strategy of supporting local governments in their design and delivery of nationally led social protection systems. This includes adjustments to the local context in each country and situation.

Household food security (DAC 430.72)

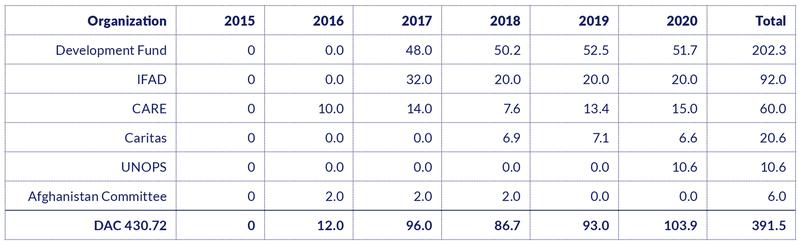

Under DAC 430.72, the Norwegian NGO the Development Fund is the main partner (NOK 202.3 million), out of the total of NOK 391.5 million. Most of this, in turn, goes to Ethiopia (NOK 96.8 million) as part of a broad program with many different components, but with a focus on agricultural production rather than transfers to households. There are many local partners, with some partners implementing both agricultural development projects (DAC 311) and food security projects, which include school meals.

The support via IFAD goes to its program for displaced people in Niger (NOK 92 million). The focus is on supporting the livelihoods of displaced people. This is part of a multi-country program that has a temporary work component. CARE is also working in Niger (NOK 60 million) in support of agricultural development through what they name as a farmer centered research for development approach. We conclude that the multisector DAC 430.72 (food security) code include projects that have some smaller social safety net components.

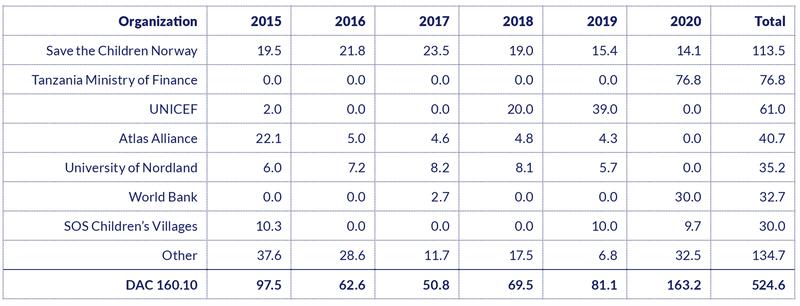

Social protection (DAC 160.10)

Under DAC 160.10 the largest disbursements go to Save the Children Norway through a general agreement that covers many countries, since 2019 this has been named as the Leaving no child behind program. Over the full period the largest disbursements have been to the organization’s programs in Myanmar, Somalia, Zimbabwe, and Ethiopia. These are child protection programs, with some transfer components according to the results framework, that is, school scholarships/conditional cash transfers, and school feeding programs. The second largest disbursement was to the Ministry of Finance in Tanzania, with all NOK 76.8 million disbursed in 2020 for the Ministry’s Social Action Fund to implement a Productive Social Safety Net program with a cash transfer component according to the project description.

UNICEF received NOK 40 million over 2018-19 for its global thematic fund for social inclusion. These are so-called soft earmarked funds. The results framework indicates that there may be some cash-transfer components. The Atlas Alliance focuses on inclusion of people with disabilities, with disbursements going through broad programs, and core partner countries being Malawi and Zambia. We find no clear household transfer component. Nordland University has received NOK 35 million for retraining of military officers in Ukraine, illustrating that also under this DAC code not all disbursements are for social safety nets in the strict sense defined above. The World Bank received NOK 30 million in 2020 for a Covid program on the West Bank in Palestine, with a cash transfer and a cash for work component. The support for SOS Children’s Villages appears to be general programs of capacity building among local partners, with no clear household transfer component. Main partner countries are Malawi and Zambia. In conclusion, not all programs coded as social protection (DAC 160.10) have clear social safety nets components.

School feeding (DAC 112.50)

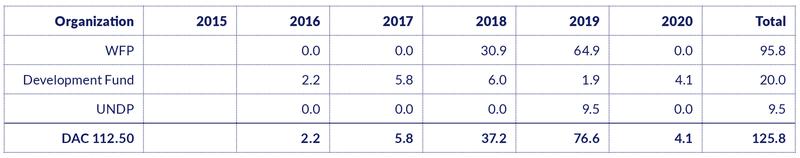

Under DAC 112.50 the main disbursements are the NOK 95.8 million in 2018-29 for the WFP school meals programs in Malawi and Mali.

UNDP also had a program in Malawi, in 2019, which was for homegrown school meals, and thus intends to help developing the local agricultural production. There is little detail on what this means in reality. Ideally food is grown and potentially prepared by the children themselves, or purchased from local farmers, but with the meals served at school. The Development Fund also ran a homegrown school feeding project, in Ethiopia, where they appear to buy food from local farmers.

Conclusions regarding direct ODA to social safety nets

Total disbursements to the four core DAC sectors over the six-years period added up to NOK 4.2 billion, out of which NOK 2.5 billion (60%) was emergency food assistance (DAC 720.40) via the World Food Program, with NOK 1.1 billion (25% of the total) going to Syria, Lebanon and Jordan. There is limited information in the public domain on how these funds are spent beyond general statements saying that food is allocated to households. The other relevant DAC sectors include support for food security (DAC 430.72) with a focus on agricultural development, potentially with some smaller social safety net components. The social protection (DAC 160.10) programs focus on child protection, with some safety net components in terms of scholarships and school feeding. Other social protection programs have cash transfer components, while some programs, including programs for disabled people, appear not to have social safety net components. Finally, there is support for school feeding programs (DAC 112.50), which in some cases are combined with agricultural development programs. Economists have favored cash-transfers as the most direct way of lifting people above the poverty line. The safety net programs supported by Norway do not appear to have permanent poverty reduction as the immediate goal. Instead the transfer programs are intended to help people through emergencies, where most of the funds go, or in combination with other instruments to increase school enrollment or support agricultural development.

1.2 Imputed aid via multilateral organizations

A large part of Norwegian ODA is allocated as core support (DAC-code 910) to cover administrative costs for multilateral organizations. These organizations have their own development programs that are coded with other DAC-codes. One may argue that Norwegian ODA in support of the administrative costs of the multilaterals are ultimately supporting the sector-wise programs run by the multilaterals. It is common to calculate this so-called imputed aid by calculating the split of DAC-910 ODA from a donor, such as Norway, that goes to various sectors (as defined by DAC-codes) implemented by the multilaterals. This implies to multiply Norwegian ODA to a multilateral organization with the share of that organization’s own ODA to each sector. We have done this calculation for the two largest sectors from Table 1.1, DAC-160.10-social protection and DAC-720.40-emergency food assistance. For school feeding there is basically no imputed aid (NOK 0.14 million via FAO in 2019). For DAC-430.72 there is only full report in the Credit Reporting System for 2019 (despite this sector code being used in the Norwegian system earlier). For 2019, the total amount of imputed aid to 430.72 was only NOK 5.8 million (via UNDP, WFP and FAO), a relatively small amount as compared to the NOK 93 million of direct aid reported in Table 1.1.

For DAC 160.10 we find that the total imputed aid to the sector, as reported in Table 1.7, is larger than the direct aid reported in Table 1.5 when we consider the shorter time period.

We see that four multilaterals stand for 96% of the imputed aid for social protection, with IDA, the World Bank’s development agency, as the main actor with about 100 projects in 2019. This is partly because Norway contributes about NOK one billion per year in core support to IDA, but also because IDA contributes significantly to social protection programs, with about 6% of its ODA going to DAC-160.10. Most (65%) of IDA’s support to social protection in 2019 went to three countries, Bangladesh, Ethiopia and Nigeria, with a rural productive safety net program in Ethiopia receiving 20% alone, and the second largest program being a safety net program for the poorest in Bangladesh. UNFPA has one large contribution, but only in 2015, for a multi-country program against gender-based-violence. The other multilaterals have only smaller programs. The largest UNICEF program is the Adolescent Development and Participation (ADAP) in the MENA regions, while the largest UNDP program is supporting financial inclusion in Chad.

The largest program, the rural productive safety net program run by IDA in Ethiopia has clear household transfer components, and in that sense may be considered as one of Norway’s main contributions to social safety nets. But recall that this is imputed aid. Norway contributes towards IDA’s core funds, and not directly to this program, in contrast to other donors, such as USAID, DFID and Danida. The second largest program, the safety net program in Bangladesh, on the other hand, is not as well documented, but appears to be a broad support to the Bangladesh government in their management of social safety nets, although in the early phase it appears to have more tangible components, including a workfare program. The World Bank has related programs though in Bangladesh that appears to be more directly related to safety nets.

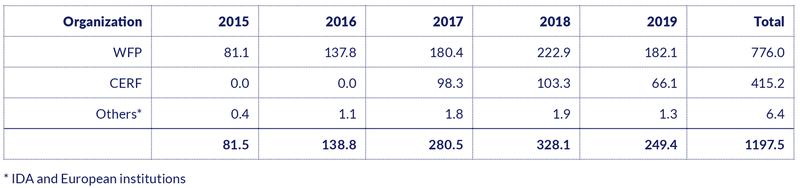

Table 1.8 reports on the imputed aid for emergency food assistance. The imputed aid via WFP is substantial, at about 30% of the direct aid from Norway to the WFP. The WFP is a major partner for Norway, it receives about NOK 300 million per year in core support, and since the main activity of the WFP is emergency food assistance (about 60%), the imputed aid is relatively large. Similarly, another UN organization, the Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF) receives about NOK 450 million in core funding per year, with emergency food assistance being about 20% of their activity. Note that prior to 2017 there is no ODA reported from CERF in the Credit Reporting System of OECD-DAC.

There is no direct aid to CERF from Norway beyond the core support. All aid from CERF is humanitarian (DAC 700), with a significant amount to food emergencies as reflected in the imputed aid in Table 1.8. But note that CERF, in turn, allocates most of its food aid via the WFP. Thus most of the imputed aid in Table 1.8 is ultimately allocated through the WFP.

Conclusions regarding imputed ODA to social safety nets

A relatively large fraction (NOK 50.5 billion, or 23% of all ODA over the period 2015-2020) of Norwegian aid is core support to multilateral organizations. This is, in principle, to cover the administrative costs of these organizations. The direct (earmarked) ODA from Norway via the multilaterals to various sectors is a slightly larger sum (NOK 63.9 billion), and has, when it comes to the allocations to safety nets, been covered in the previous section. The core funds can, however, be interpreted as a support to the sector-specific programs that the multilaterals run themselves. If we do so, then we find that food aid via the WFP is the main channel of Norwegian aid, both in terms of imputed and direct ODA.

2. Classification of Norwegian ODA in support of social safety nets

2.1 Emergency vs long-term assistance

We found in the first section that emergency food assistance via the WFP is the main channel of Norwegian ODA in support of social safety nets. Emergency assistance is a response to aggregate risk, in contrast to idiosyncratic risk. Poor societies are in many ways able to handle idiosyncratic risks, where people help their neighbors in times of need knowing that the next time it may be themselves that need help. Aggregate risk on the other hand, where whole villages, regions, countries or even groups of countries may be hit at the same time, will normally require aid from the outside. Wealthier countries will normally handle these situations themselves, while poor countries will regularly need international support. There is thus a well-founded rationale for large shares of Norwegian aid in support of social safety nets being channeled to emergency assistance. The modality of emergency aid has, however, been changing over time, with cash transfers gradually replacing food distribution, which will be discussed in more detail below.

We know from the welfare states, such as the Nordic countries, that a social safety net may also cover idiosyncratic risk, and thus to a small or larger degree replace the informal safety nets that exist in close-knit societies. The rationale, or at least the implications of this, is to make people less dependent on their family and neighbors. As a result one can more easily migrate to other parts of the country, marry at own will, and have more control over own income. Within village this may make people less dependent on powerful neighbors, in particular local employers cum moneylenders, and thus tilt local power-dynamics. Safety nets, where households receive support in time of need, come with their own problems, with the identification of “time of need” being the essential one. How should one weigh the insurance element against the need of permanent support to some households? We now turn to this issue.

2.2 Targeted or universal programs

Whether a program is defined as universal or targeted depends on definition. The Norwegian welfare state is commonly used as an example of a universalist approach. The largest transfer programs in Norway are pensions, support during sick-leave, subsidized health care, unemployment benefits, and child benefits of different kinds. These programs provide a social safety net, so that people are covered basically in any life-situation, whether they lose their job, needs medical assistance, get children, or simply get old, thus in that sense universal. But all these transfers depend on certain characteristics of the recipient, which involves targeting, and these characteristics are more or less easily verified. One of the largest employers in Norway is NAV, the government institution that verifies demands on the welfare state and disburses the household transfers. NAV interviews people and judge whether they are no longer able to work, and thus eligible for disability pension, or if they are able to work whether they should receive (depending on previous taxable income) the state unemployment benefits or only a basic support from the municipality. NAV also tailor-makes work-training based on individual interviews. Old age pension may be considered universal, but is of course targeted to people above a certain age, with the pension itself depending on life-time income as verified by NAV. Thus the universalist welfare state is based on individual treatment, with the package of support being targeted to each person depending on their life situation and prior income, with the higher paid getting the largest transfers.

What can poor countries learn from the welfare states? The fact that people receive support according to their previous taxable income may explain the widespread support for the welfare state. In poor countries, however, one normally discusses the opposite case, that is, whether the poorest segments of society should receive more than others, or, as an alternative, whether there should be a universal basic income. A main argument for the latter is to reduce the costs of identifying the target group of poor or marginalized people.

A universal transfer to everyone will by construction remove the targeting cost and exclusion errors, since there is no longer a need to identify a target group. The extra transfers may of course cost more than the targeting costs, and the distributional effects will depend on the exclusion and inclusion errors of the targeting system. If participation is made relatively costly for the non-target group, by way of low paid manual work, or other conditions, such as sending children to public school, then the costs of targeting may be low, and a targeted transfer system may be cost-effective.

A targeted transfer may be short-lived, in contrast to a universal transfer. It is an old question within development economics, and social policy in general, whether poor people are in a poverty trap, and can be lifted by way of a one-time large transfer. If poor people lack the means to generate an income, why not rectify that problem, instead of providing permanent support? We shall see below that poverty traps may be the result of multiple constraints, so that the one-time transfer may have to be a one-time combination of interventions.

Thus a universal safety net does not need to be a universal basic transfer to all. On the contrary, in a poor country it appears that public funds, including development assistance, can be used more efficiently in support of maintaining human capital and other types of capital for the poor in times of emergencies, preferably by use of some self-targeting mechanisms such as work efforts or other conditions. Also with respect to long-term development it appears that short term, but multifaceted, support may help people out of a poverty trap. Below we will discuss some of the programs supported by Norway that are in support of these targets, before we turn to relevant knowledge gaps. While above we have already noted that most of the Norwegian support is emergency aid, and thus in support of the first target of maintaining human capital (education, health, nutrition) throughout crisis.

2.3 Conditional versus unconditional transfers

Related to the question of targeting is the issue of conditional versus unconditional transfers. With conditions added one may exclude households that find the conditions too costly for them. Cash or food for work can be considered as a conditional program, which, depending on the amount and type of work, may be attractive only for poor people, and thus constitute a self-targeting scheme. Norway supports some work-fare programs, such as the UNDP program in Gaza, mentioned above, and the World Bank programs in Bangladesh.

Conditional support may also be used, not to self-target specific groups, but rather to meet two objectives by one mean. Some of the Norwegian support is of this kind, with school feeding as the typical example. Children get a meal at lunch, assuming that they in fact go to school that day. The implementation here is essential, as one can imagine programs where families receive support to grow their own food, assuming that this will allow the children to go to school. In worst case the children may stay home to grow the food, for example by working in the vegetable garden and the maize fields. This will be counterproductive if the combined target is to promote both nutrition and education. Scholarships may have similar incentive problems, where children go to school the first weeks, and then leave when the scholarship is received. But in general, as we will see in the section on knowledge gaps, research has found conditional transfers to be successful, also when compared to unconditional transfers. Most of these programs have been implemented by governments in Latin America, while this is still a minor element in Norwegian development assistance, with school feeding being a major component. There are also some programs in the Norwegian portfolio that are conditioned on people using health services.

2.4 Cash vs kind

As discussed above, in-kind payments may be considered as a self-targeting mechanism. Food aid may be more attractive for poor people as there may be a social cost for the wealthier in showing up at food distribution stations, and a direct trading cost if the food is not to their liking and they need to sell it. Food aid also mimics conditional transfers in the sense that the transfer is tied to food consumption. The degree of conditionality depends on the local food market. If the household can easily sell the food in the market, then food aid is in principle an unconditional cash transfer. If no trade is feasible, then the transfer is conditional in the sense that it meets other targets of the implementing agency, such as child nutrition, and if given at school, education.

Many of the programs supported by Norway have implemented intermediate solutions between cash and in-kind transfers. A potential problem with cash transfers is well known from many countries, including Norway from the time when salaries were received in envelopes at the end of the week, money in hand can easily be spent on the way home on payday. Cash on a bank account reduces this problem. Bank accounts come in different forms, and can be more or less tailor made to poor people. Access via a mobile phone allows transfer to family members elsewhere, which is useful for migrant labor, and transfer to shopkeepers or others when cash is needed. The Business Correspondent model in India is an organized version of the latter. The bank account can, in principle be linked to government registers of target groups, such as people with Below Poverty Line (BLP) status in India. Such financial inclusion programs have been equally important in other parts of the world, with the M-Pesa program in Kenya and the Progresa program in Mexico being the best known examples.

While money on an account can normally easily be turned into cash, there are other intermediate solutions that are more similar to in-kind payments, such as food-stamps, or other sorts of coupons, and store-credit. As for in-kind payments, markets will exist for food stamps and other forms, with amount of trading depending on the local market, including any control mechanisms. As discussed above, the WFP is a main vehicle for Norwegian transfers to households in need, and WFP has an explicit policy of combining the different solutions discussed here, with the mix depending on the local context. In particular in emergencies in places where the food market is expected to function well and the target group is easily identified, cash may be the most efficient way to help people in need.

2.5 Multifaceted programs

In the mapping of Norwegian aid in support of social safety nets we found that most programs had only one component among many that was in fact a transfer program. These broad development programs had different additional components. Transfers are tied to the use of health services or children attending school, or they are part of broader agricultural development programs, or broad national level reconstruction programs such as the Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund in Afghanistan. We also know, from the history of Norwegian development assistance, that broad-based rural development programs used to be a major strategy. With the shift towards market led solutions in many donor countries in the 1980s and 90s also the development strategies changed and the focus shifted towards state-building, democratization, trade and economic growth. Today we see that economic growth has reduced poverty in some parts of the world, noticeably in China and some other Asian countries, while poverty is still high in rural Africa, and parts of India and South-Asia in general. There appears to be village level poverty traps where people meet multiple constraints that will have to be solved simultaneously. Norway now supports such broad rural development programs, in particular via multilateral organizations such as the mentioned rural productive safety net program in Ethiopia and the safety net program for the poorest in Bangladesh. We will discuss in more detail below how such multifaceted programs should reflect deeper analysis of the underlying constraints that poor people meet.

3. Knowledge gaps

The literature on social safety nets is extensive, with numerous reviews of different parts of the literature. Instead of making another one, we will focus on a few selected issues motivated by the mapping above and a recent report by Norad that reviews the literature. The Norad report points to some critical issues where findings are not definite. We have gone to the underlying research with the aim of identifying the source of any conflicting findings, to see whether local context, target groups, research questions or research methodology may explain any apparently conflicting findings. Here are some cites from the report (translated by us), and specification of what we will discuss in more detail below.

Conditional vs unconditional transfers

“Studies that have compared the effects of conditional versus unconditional transfers have no clear conclusions (ikke entydige konklusjoner)”. The note concludes that context matters, which we will discuss below. The literature that studies conditional or unconditional support is extensive, while there are not so many studies that compare the two.

Cash transfers and long-term development

“There is a need to understand how cash-transfers can be combined with long-term development projects to improve long-term development”. Below we will in particular discuss how emergency aid may counteract permanent loss of productive capabilities and recent research that show how multifaceted (cash-plus, graduation) anti-poverty programs can help households’ transition from permanent poverty to a positive development path.

Gender programming

“There are mixed findings when it comes to the effects of social transfers on women and gender equality”. We will attempt to reconcile these findings based on existing research.

Implementation (digital solutions)

The report also discusses a number of implementation issues, such as coordination with local governments when it comes to long-term development, the integration of emergency and long-term assistance, identification of target groups versus universal systems, and the use of digital solutions. Many of these are already discussed, and we will below focus on the relatively thin research on digital solutions.

3.1 Conditional transfers

Governments and aid agencies will normally have multiple goals, and cash, or in-kind, transfers can incentivize people to utilize government services in support of these goals. This is, in some sense, the opposite of user-fees, as people are paid to utilize services, such as education and health services. One rationale for this is that there are positive externalities, as not only the person itself will benefit. Vaccines and treatments of transmissible diseases are standard examples. People may not consider the full benefits for society from utilizing these services. Whether the price should be negative, as with conditional cash transfers, or only subsidized, will be a trade-off between the positive externalities and the public costs of raising the necessary funds. In particular for foreign aid it appears to us that the use of funds does not always reflect the marginal cost of funds, but ideally vaccine subsidies should be weighed against the social benefits of other use of public funds, both within and beyond the health sector. Also education may have positive externalities as a child with, let us say, reading skills may help family members and neighbors who cannot read. And at the macro level the full benefits of an educated workforce may extend beyond the private benefits for the households.

Beyond positive externalities, governments or aid agencies may also be concerned with the interests of children, or other household members, with a limited say on how unconditional transfers are spent. One may realize that even if money is given to the child, or others with a limited say within the household, they may not be able to spend it to their own liking. The parents may, in theory, not see the full benefits of education, which in turn is a rationale for transfers conditioned on school attendance.

Conditional transfers are thus intended to divert household expenditures and other behavior away from what the household would do in the case of unconstrained transfers. If the conditions are that children go to school, then this will affect both income (from child labor), and potentially how the lower incomes are spent (clothing, school materials, and potentially food expenditures for the children). The empirical test that will separate the impacts of the two types of transfers is thus whether the composition of household expenditures and other household behavior are in fact affected, and if so, in the intended direction. Many of the reviews of the literature do not focus on this essential issue. Instead of comparing the impacts of conditional and unconditional transfers of the same size, one tend to report the impacts of either conditional or unconditional transfers compared to no transfers. This may have interest, but will not help an agency deciding whether a particular transfer should be conditional or not.

Transfers conditional on sending children to school have been a major research focus. One influential review reports findings from 35 different studies comparing the impacts of conditional and unconditional transfers on schooling. It was found that conditions work, but only for programs where the conditions “are explicitly conditional, monitor compliance and penalize non-compliance”. While they found no significant difference when they included all 35 programs. There is thus clear evidence that it is not the context, but rather the implementation of the program that matters. If a program conditions the transfers on people actually sending children to school, and this is in fact monitored, then, as we may expect, people send their children to school.

The choice between conditional and unconditional transfers should depend on the aim of the program. If the aim is to relax liquidity constraints, or help people in need, then unconditional transfers is the right choice, but if the aim is also to incentivize people to send their children to school, or utilize health services, then well-designed conditional transfers will be in place. In fact the flagship Progresa program is found to have positive impacts on a number of indicators, although there are still relatively few studies of long-term impacts. A recent review reports on the studies of long-term impacts, where available evidence is best on schooling outcomes (although they also cover health interventions, and labor market outcomes). The most robust findings are that: “Most studies find positive long-term effects on schooling, but fewer find positive impacts on cognitive skills, learning, or socio-emotional skills”.

When it comes to liquidity constraints, there are arguments in favor of unconditional cash transfers, as the additional targets on which conditions may be placed will be hard to identify. One condition may be that they start a profitable business, but then a loan may be a better instrument. The exception here is the case where potential entrepreneurs are so close to subsistence consumption that they cannot even handle repayments of a loan. An example that we have studied is rickshaw cyclists who rent the rickshaw despite that the weekly repayments on a rickshaw loan will be only marginally larger. In such cases, where poor people run a profitable business by way of leasing the capital needed (rickshaw, sewing machine, livestock, examples are many), an unconditional cash transfer (or equivalently a transfer of ownership of the asset) may lift them out of a poverty trap. One multi-country study confirms this, cash transfers have the largest impacts on agricultural production when liquidity appears to be the binding constraints, and the households have available family labor to utilize the production capacity. In other contexts other constraints may bind and multifaceted programs may be the solution.

3.2 Cash transfers and long-term development

The Norwegian government states that “cash transfers contribute to bridge humanitarian assistance and long-term development”. The core argument for this is that cash transfers contribute to maintaining in particular human capital throughout emergencies. Norwegian assistance focuses on keeping children in school, sustaining food consumption, and providing health services throughout crisis. Norway also intends to strengthen its support to social safety nets, and see this as a contribution towards long term development. As discussed above, there is a potential trade-off between universal permanent transfers and a universal safety net that kicks in when people are in need, either due to an emergency or as a one-time transfer to lift them out of a poverty trap. In this section we will focus on the latter.

Research indicates that there are geographic pockets of rural poverty, where cash transfers will not be sufficient to lift people out of extreme poverty. In remote parts of Africa, and some parts of South-Asia, the extreme poor meet multiple constraints, and a combination of interventions is necessary to lift them out of poverty. These interventions should, in principle, be temporary, with people accumulating further wealth by themselves after they have passed a critical threshold. The relevant constraints are:

- Subsistence constraints (basic nutrition)

- Insurance (health, agriculture, social safety nets)

- Human capital (education, training, nutrition, health programs)

- Physical capital (microcredit, savings, livestock)

Even people who in principle are willing to accept risk, may be forced to behave as if they are risk averse if they live near a subsistence level. Villagers may insure each other against idiosyncratic risk, while aggregate risk, such as natural calamities, pandemics or village-wide introduction of a new agricultural technology, may require transfers from the outside. These may be in form of insurance at a larger scale than the informal insurance one finds in villages, or just transfer in times of need (thus basically insurance without the ex-ante premium payments).

The subsistence constraint may bind even without risk. As discussed above, this may hinder profitable investments, as even repayments of loans may bring them close to, or even below, subsistence consumption. If markets work well, then a one-time large transfer will make the poor able to get out of poverty. They can buy sufficient food to pass nutritional constraints, they can get access to health, education and training, and buy the necessary physical capital needed to improve their income generation, whether that is in agriculture or other businesses. But we know that markets do not work well in remote and poor areas. Still, one-time interventions may be sufficient if they cover all relevant domains. In the most remote places this may include a package of development programs:

- Subsistence constraints: cash and in-kind transfers, including work-fare programs, nutritional supplements, agricultural inputs.

- Insurance: health services, agricultural insurance, emergency aid, social safety net

- Human capital: primary and higher level education, skill training, agricultural extension services, nutritional programs, health services

- Physical capital: microcredit, savings programs, livestock programs

Multifaceted rural development programs were popular in the 1970s, and later replaced by other development ideas, in particular with a focus on democratic institutions, economic growth and redistribution. But the old integrated rural development programs put less weight on underlying market failures, and more on infrastructure, coordination at the village level, and basic needs of the households. These are all important, but today we can benefit from decades of research on underlying market failures in the rural credit, labor and land markets.

We know from the early writings within development theory that there is a need for a balanced growth path, where countries go through a structural transformation with economic growth in all sectors. Investments in agriculture will release labor and economic surplus that can be utilized in other sectors, both within the rural economy, and in urban areas. Thus today we know that there is no conflict between the development theories of earlier decades, that is, we need both economic growth and redistribution via social safety nets, as well as integrated rural development programs. In contrast to the 1970s, the world should be able to afford the necessary policies to include also the remaining pockets of extreme poverty in remote areas in the development process. In particular China has demonstrated that temporary policies can have permanent effects.

With the randomized control trials (RCT) revolution within development economics, such multifaceted development programs have been tested on a large scale, and have been found to have both short- and long-term impacts on poverty reduction and a number of other outcomes. In the short to medium term (three years) the programs increase households’ net worth, income, consumption, and health. Some of the programs have now been studied for 10 years, and show continued impacts on the same indicators, including spillovers on people who were not targeted. It is also found that if one drops some of the program components, then they may not work.

In the mapping above we found that most of the Norwegian assistance in support of social safety nets have relatively small cash or in-kind transfer components that are part of much larger development programs. This opens up for systematic comparison between programs, and potential adjustment of programs based on available research on what packages may work. It has been outside the scope of the present report to say whether any of the programs supported contain the full package of program components that appear to be successful in lifting people out of poverty. But based on the program description, the IDA supported rural productive safety net (PSNP) in Ethiopia and the safety net program for the poorest in Bangladesh are the closest we get among the larger programs. Some of the NGO supported programs are also broad-based integrated rural development programs. The PSNP has been studied by many, and a recent review indicates a number of positive impacts.

3.3 Gender programming

The role of female empowerment in household decision making is a prime example of how the choice of method, and implicitly the underlying theory, affects your conclusions regarding impacts of a policy intervention. It is well established that measures of female empowerment are positively correlated with a number of welfare indicators. Women tend to prioritize nutrition and education for their children, and in particular for girls, and the more empowered women more so. This does not imply that a cash transfer to women will lead to higher spending on girls’ nutrition and education, beyond the normal income effect that will lead to an increase in all spending. A cash transfer will only have an additional impact on girls’ welfare if it strengthens the female bargaining position within the household. One can easily imagine the opposite: a woman receives cash from an NGO activist, or by some other means from an external agent or program. This can be considered by her husband as external intrusion into family life, and lead to a backlash where he takes more control over the woman’s life.

Despite that one shall not necessarily expect cash transfers to alter female empowerment, it is not uncommon to attempt to test theories of female empowerment by way of an RCT where cash is given to women and men, and then measure whether cash to women leads to higher spending on girls. If there is no statistical difference between the spending by men and women, then one may conclude that there is no support for the female empowerment theory. This will be misleading, since the finding may reflect that women and men have the same preferences, that the sample size is too small, or, more importantly, that the man has full control over the woman’s spending. If the latter is the case, then a negative finding is rather in support of a theory of female empowerment.

To test the theory one will have to compare the spending of empowered women, with the spending of women who are not empowered. This can be done on any type of data, not only from RTCs. If the budget share for, let us say, girls’ education or food intake, is larger among empowered women than for other women and men, then we know female empowerment matters. The research mentioned above has tested this in many different contexts and with different measures of female empowerment. The implication for cash transfers is that one will have to design the programs so that they are likely to affect the female bargaining position within the household.

Although the literature on the role of female empowerment in general is large, there are not many studies that systematically study how cash-transfers affect female empowerment. Any cash-transfer program can be used to investigate this by implementing different versions of cash-transfers. To set up the research, there is a need for theory that may explain why a cash transfer will alter the female bargaining position within a household. Why wouldn’t an additional cash transfer be controlled by the husband to the same extent as any other income? In principle this can be tested by varying the way women receive the cash transfer, but this is rarely done in RCTs. From earlier research we know that it may potentially matter, for example income earned by the woman may give her more power than unearned income (such as a cash transfer).

The lack of theory in many RCTs is a major concern. On top of this comes the fact that a nil-result does not prove much, the standard approach in empirical research will be to set up a nil-hypothesis, and a rejection will support your theory. And if there is support for the theory in many different contexts (as you can test if you have large datasets) then the finding is robust. The established literature on female empowerment has gone through this process of gradually testing theory on large datasets in different contexts, while the recent evidence from a few RCTs with nil-results is too limited to change the main conclusion.

This does not imply that well designed RCTs cannot provide new insights. As mentioned, RCTs, and other intervention studies, can provide new information if one compares different ways of giving women a transfer. Variation can happen along many dimensions:

- wage vs transfer (as in the mentioned study)

- cash vs kind

- cash in hand vs on an account

- cash vs asset

And the transfers can be combined with a set of other policy instruments we know strengthen female empowerment. This can be programs to strengthen female political participation, self-help groups, entrepreneurship programs, female quotas in hiring processes, information campaigns, inheritance rights, divorce rights, and many more.

Going beyond RCTs, the World Bank has added a large gender component to its Living Standard Measurement Surveys, the so-called LSMS+ program, which has led to a number of new publications on the role of female empowerment in agriculture. Adding other data sources, including intervention studies, this literature on women’s role in agriculture is large, and cannot be summarized in this short report. At a methodological level the core problem is the same as with all farm-household models, that all family members work on the same land, and normally pool their resources as well as the produce. The LSMS+ surveys attempt to dig into this black box, by asking about a wide range of individual specific user rights to land, in addition to individual time-use, and spending.

The general finding from all this literature is that female empowerment matters for household decision-making. To strengthen women’s say within the household is, however, a different matter. One cannot expect a cash transfer in itself to alter intrahousehold power relations. But if the transfer is somewhat related to powers outside the household that can alter the power relations within, then a cash transfer may have an impact. Altering those external conditions may, however, be the essential element of the intervention.

Any attempts to alter intrahousehold power-relations need to take into account a potential backlash where the husband use alternative means to maintain his position. This can be straightforward violence, with gender-based violence (GBV) potentially being an unintentional effect of an intervention, or the husband can resolve to other means that alter the woman’s bargaining position. He can threaten divorce, which may have multiple economic implications, or he can keep her away from work, school, the market, or visits to her own family, potentially by threats of violence. One can thus imagine that GBV will first increase as a result of an intervention that strengthen female empowerment, followed by a decline in GBV as the woman in fact gets a stronger position within the household. If this is the case, then the time of measurement of the impact becomes essential. To get quickly over the intermediate phase, it is essential that the woman’s renewed outside option is credibly established. This may require a combination of legal reforms in support of economic empowerment of women and a prior local campaign, that may have to last for years, to ensure support for the transition.

3.4 Digital solutions

Digital solutions within development assistance do not have to be very advanced. For transfers, the simplest possible solution will be mobile talk-time. This can be implemented even on an old-fashioned mobile phone, where people get paid, let us say for one day in a public works program, in terms of phone credit. In many poor economies there is a perfect market where phone credits can be cashed in among friends or at the nearest street corner. From phone credits the digital solutions can be gradually more sophisticated. For those without a smart phone one can in India go to a business correspondent as discussed above. This will normally be a local businessman with cash on hand that can add or withdraw funds from his clients’ bank accounts using his own smart phone. The next step will be that the client can check the balance, and transfer money themselves, using their own smartphone, as in the M-Pesa system in Kenya. For adding and withdrawing cash they also will have to go to an agent as in the business correspondent model. The final step is full scale online banking that is linked to an ATM network. The lower rungs of this value chain can be linked to various micro-finance solutions, with self-help groups, or other types of community organizations or microfinance groups, helping people to save, invest and developing skills related to income-generating activities.

Another direction of digital development will be towards integration with other forms of digital solutions, with government transfers and tax systems being the core examples. As mentioned above, the NREGA work program in India is one example of a well developed system. There is research that points to the cost-effectiveness of linking the NREGA payments to digital registers, including less leakage. While others point out that digital solutions will not necessarily solve the underlying targeting problem.

Most reviews focus, however, on the broader literature on financial inclusion. Financial services include insurance, saving and credit systems. We have already discussed savings and insurance, which is one way to create a social safety net. The literature on microcredit is a large one, with numerous reviews of the literature. The core finding is that people are to some extent credit constrained, and spend new funds from microcredit programs in a number of ways, including productive assets, consumer durables, and for example marriage expenses. As we may expect, microcredit does not lead to transformative changes as concluded in a recent review: “The impacts of financial inclusion interventions are small and variable. Although some services have some positive effects for some people, overall financial inclusion may be no better than comparable alternatives, such as graduation or livelihoods interventions.” Which thus brings us back to the multifaceted graduation programs discussed above.

In conclusion, we cannot see that there are any clear knowledge gaps when it comes to digital solutions in transfer programs. Transfer programs are in general switching to transfers on an account instead of in hand, with recipients having access via mobile phones. This will normally reduce the risk of leakage, and is found to increase savings. Digital registers may reduce the costs of targeting, and if recipients are listed online it will increase transparency, although at the cost of loss of privacy. Norway is already supporting digital solutions, including support to the World Bank’s efforts in helping countries developing digital solutions. But also by supporting a wide range of transfer programs as discussed throughout this report, programs that tend to shift towards cash transfers on an account.

4. Conclusions

Norwegian ODA in support of social safety nets is normally integrated in broad development programs where transfers to households are relatively small elements as compared to the overall budgets, and with most of the aid classified as emergency assistance. Broad programs do, in principle, allow for the necessary flexibility to turn emergency assistance into long-term development. We know it is important to sustain human capital during emergencies. Children need to go to school, and all household members need sufficient food to stay healthy and be able to maintain their livelihood activities. Emergency aid is thus a necessary part of any safety net.

A larger question is whether a safety net should in fact be a safety net, and thus provide temporary support when people are in need, or whether it should provide a permanent (safe) income to all, or to some target group of poor or marginalized people. The Norwegian welfare state is of the first kind. It provides a safety net in terms of transfers to people in need, transfers that in Norway increases with prior income. There is a discussion in both rich and poor countries whether transfers should instead by universal. In Norway this may reduce the costs of the welfare state if they replace costly transfers that depend on income. In poor countries universal transfers mean transfers to large groups that today are not targeted, and are thus potentially very costly.

Returning to emergency aid that may be integrated in broad development programs, the latter may have education, health, and food components, including school feeding and agricultural development interventions, as in many of the programs supported by Norway. This implies that they may already have many of the components of well functioning multifaceted development programs. Emergency aid provides insurance in times of need and sustain human capital. To support long-term development in remote places one should consider not only to help people during emergency, but also to target the extreme poor with support over a few years to lift them above subsistence level, and help them with skill training, including in agriculture, and some assets, such as livestock, so that they in the longer term can develop higher earning livelihoods. In the most remote places this means that households combine agricultural activities with small-scale non-farm livelihoods, while some household members migrate for work.

Within all these programs one may prioritize women to strengthen their position within the household. It is essential then to take into account existing power relations, as the husband, or other male family members, can in principle take control over any transfers to the woman. To avoid this, the interventions need to intrinsically improve female empowerment in a way that will be outside his control. Improving her human capital is an important example, which may include primary education for girls and skill training for adolescent and adult women. Interventions can also strengthen women’s legal rights with respect to marriage, divorce, property and inheritance rights. Such legal reforms will normally have to be followed by campaigns that target the underlying social norms that in most societies are intertwined with the legal system.

Cleverly designed asset, cash and in-kind transfers that take into account underlying power-structures may strengthen female empowerment. Some of the programs supported by Norway are of this kind. School feeding programs are important for female students, as they are more easily kept out of school. Agricultural development programs that focus on small-scale vegetable production is another example, as this is normally the woman’s domain. Vegetables will improve nutrition and give her a potential position as a businesswoman in the local market. When it comes to cash-transfers it is important that women get their own bank accounts. This is no guarantee that they will be able to keep the money out of the husband’s control, but will at least give them another means to strengthen their bargaining position within the household.

When it comes to implementation, we find that Norway supports a variety of social safety net programs, ranging from small local NGOs to multilateral organizations such as the WFP. This variation allows for learning across programs during a phase where Norway intends to strengthen its support to social safety nets. Despite the difference in size between programs, both the smaller NGO led programs, as well as the large emergency assistance programs, integrate cash and in-kind transfers in larger development programs with the aim of also promoting long-term development. The composition of these programs vary with the local context and the aims of the agencies, as we shall expect. This opens up for learning. In that process one will benefit from the recent research on the multifaceted development programs discussed above, which systematically attempt to overcome multiple constraints that poor people meet in remote areas of Sub-Saharan Africa and some parts of South-Asia.