Taxing the urban boom in Tanzania: Central versus local government property tax collection

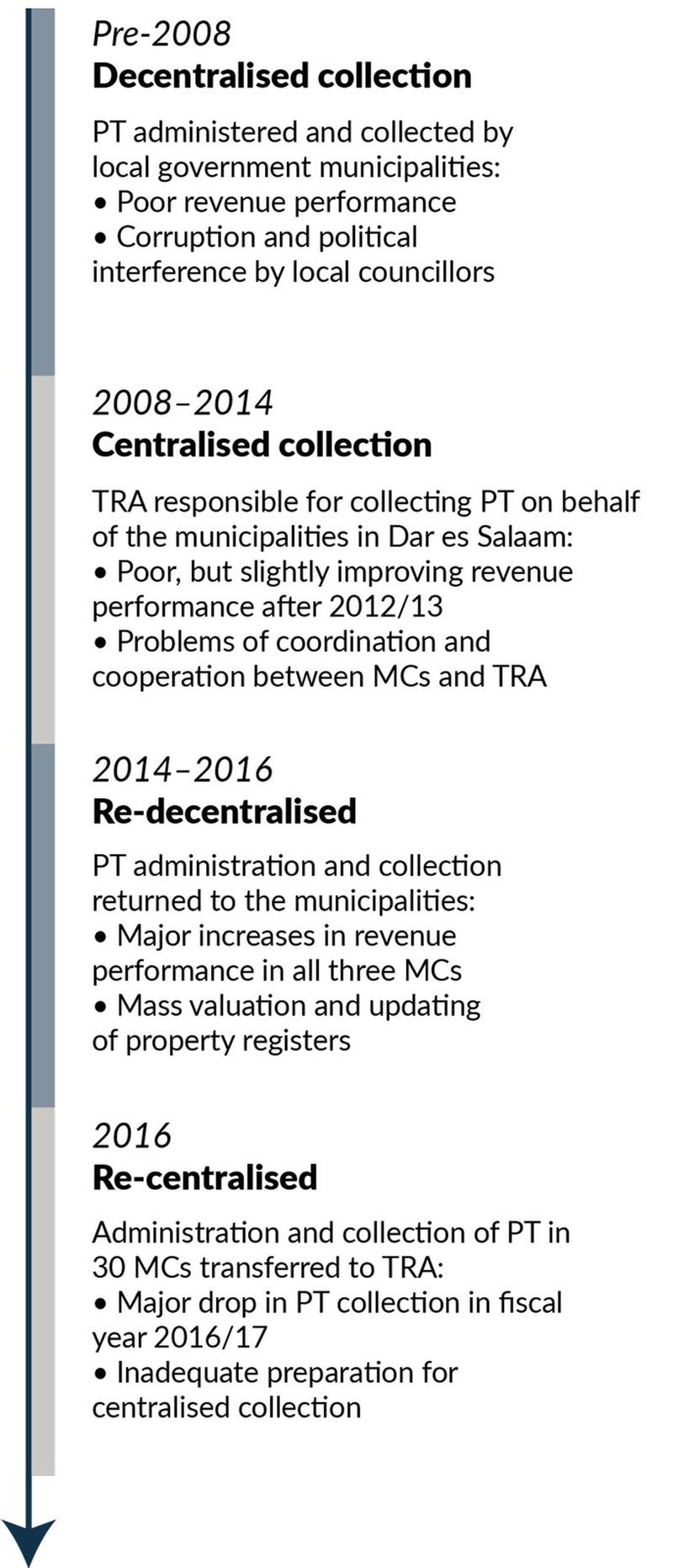

Property tax collection regimes during the last decade

A brief history of property tax collection in Tanzania

Pre-2008: Decentralised collection

2008–2014: Centralised collection

2014–2016: Re-decentralisation

Trends in property tax collection

How to explain the variation in collection performance over time?

How to cite this publication:

Odd-Helge Fjeldstad, Merima Ali, Lucas Katera (2017). Taxing the urban boom in Tanzania: Central versus local government property tax collection. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI Insight 2017:3)

Effective collection of property taxes requires constructive working relations between the central government revenue authority and the municipalities, independent of the mode of administration. Clear division of function and responsibility between the local and the central government is critical for effective policy implementation. The administration of property taxes in Tanzania has seen major changes in the last decade, oscillating between decentralised and centralised collection regimes. This briefing examines experiences with the different revenue collection regimes.

Property tax collection regimes during the last decade

Tanzania has implemented several major reforms of the property tax (PT) collection system in recent years. In 2008, a new system for PT collection was introduced in Dar es Salaam, the country’s largest city. The reform entailed shifting the responsibility for administration and collection of property tax from the municipal councils (MCs) to the national tax administration, the Tanzania Revenue Authority (TRA). The Government expected this measure to increase the revenue collection. It did not. In February 2014, the Government announced the return of PT collection to the municipalities with immediate effect. This did not last long. In July 2016, property taxation was again centralised and TRA was assigned full responsibility for administrating the tax in the country. In this briefing, we first presents the history of centralisation and decentralisation of PT collection in Tanzania. Then we examine the revenue trends under the different collection regimes in the municipalities in Dar es Salaam. We explain the variation in PT collection over time and finally, present policy implications in a concluding section{1}.

A brief history of property tax collection in Tanzania

In the following, we discuss key features of each of these collection regimes.

Pre-2008: Decentralised collection

Property tax reform was a central component of the of decentralisation process in Tanzania long before 2008 (McCluskey and Franzsen 2005: 65). However, there was serious concern among national policy makers about the low levels of PT the municipalities managed to collect. At the start of the millennium, PT accounted for 10–30 per cent of the revenues collected by urban councils in Tanzania, equivalent to less than 0.3 per cent of GDP (Fjeldstad et al. 2004). Some estimates suggest that more than 60 per cent of the potential revenue from PT remained uncollected in this period (URT 2007).

Poor administrative capacity, corruption and political interference in tax enforcement were seen to be the main obstacles to improving the PT system. Elected local councilors often intervened in tax collection and in the recruitment of revenue collectors (Fjeldstad et al. 2010). Because of this, enforcement of the property tax legislation became exceedingly difficult. Citizens also complained about corruption in the revenue collection, and that they did not get anything in return from taxes paid. Various measures to address these challenges, including outsourcing of PT collection to private agents, were attempted without much success (Fjeldstad et al. 2009).

When the National Assembly debated the 2007/2008 budget proposal for local government authorities (LGAs) in June 2007, under-collection of revenues was one of the major issues about which Parliamentarians expressed concern (URT 2007: 2). In response, then Prime Minister Edward Lowassa announced that the Government had decided to institute specific policy measures to address the challenge. One measure was to have the TRA take over the collection of PT in Dar es Salaam. TRA was considered to have capacity to substantially improve collection. At the same time, TRA could “assist and provide capacity building to the local government authorities so that they can similarly excel in collecting revenues from their own sources” (ibid. 3).

2008–2014: Centralised collection

Following the Government policy directive, a committee to establish mechanisms for the implementation of the reform was appointed in July 2007 (URT 2007). In addition to representatives from TRA, it included representatives from the Prime Ministers’ Office Regional Administration and Local Government (PMORALG) – in their capacity as the ministry responsible for local government. The committee reviewed the relevant legislation. It recommended a set of measures to be put in place before TRA could take over the PT collection on behalf of the LGAs. Since the existing laws did not allow TRA to collect property tax on behalf of LGAs, and did not allow LGAs to appoint TRA as their agent for that purpose, legislation had to be amended.

The proposed amendments were passed by the National Assembly in July 2008.{2}

TRA was mandated to collect PT on behalf of the LGAs in order to enhance revenues. The Authority was also mandated to do capacity building on revenue collection in the municipalities. The mandate was for a period of five years, starting 1 July 2008. The Minister responsible for the LGAs could extend this period for a specified and limited time. The Minister could terminate the mandate when the local government authority had developed the required capacity to collect PT.

The amended laws placed the administrative authority with TRA. Policy-related decisions in terms of setting rates or declaring an area ratable and granting exemptions were, however, kept with the LGAs. TRA would only exercise the power of tax collection. Property taxes collected by the TRA should be credited into a special local government authority account and remitted to the respective municipality in a manner agreed upon by the parties (URT 2008: Section 10). TRA should also submit a monthly report to the local government authorities on the amount collected (ibid). Senior TRA-officials interviewed in 2011, argued that this gap between the legal mandate and the practice under the new arrangement was a result of “political dynamics at play between the Ministry responsible for local governments and the involved municipalities”.{3}

Property tax collection was initiated by TRA under the newly mandated arrangement from July 2008. Their approach rested on modern principles of tax administration, including a cash-less collection system, ease of payment, well-trained tax staff with ample cross-checks, as well as sound reporting and monitoring systems. The cash-less collection system was one of the notable changes introduced by TRA. Previously, PT was collected by municipality revenue officers in cash or by taxpayers depositing payments at the municipal treasury office. This practice enabled embezzlement and corruption (Fjeldstad et al. 2010). TRA, however, required taxpayers to have a Tax Identification Number (TIN), when depositing their tax bills in a specified bank branch.

The centralisation of PT collection was seen by the municipalities and some donors as an attempt by the Government to halt the decentralisation reform that started in 2000. The ambiguous justification for the PT reform contributed to distrust between the municipalities and TRA. This lack of trust negatively affected both the design and the implementation of the property tax reform.

2014–2016: Re-decentralisation

In February 2014, the Government announced that PT collection should be returned to the municipalities. This occurred after massive lobbying by the municipalities, supported by the Association of Local Government Authorities in Tanzania (ALAT), but without previous consultations with the TRA. In interviews, municipal staff expressed that they strongly believed that collection by the municipality would be far better than that of TRA.{4} First and foremost, they argued that the municipality knew that it was collecting the money to finance its own budget. This was thought to motivate efforts to meet the revenue target. In the municipal staffs’ opinion, the re-decentralisation of property tax administration was “a perfect move”. According to a senior TRA officer, “all municipalities are very happy about re-decentralisation of PT collection because right from the start when TRA took over they were disappointed”.{5} He argued that the municipalities “have been trying to make tricks so that TRA is perceived inefficient”. “For example,” he said, “when TRA took over, all municipalities set larger targets to TRA year after year despite the fact that the tax base remained the same.”

2016: Re-centralisation

In June 2016, the Minister of Finance announced (in the Budget Speech for 2016/17) that the administration and collection of PT in the whole country should be transferred from the local government authorities to the TRA (URT 2016a: 21, para 31).{6} The Minister emphasised that the “… Government is determined to increase and strengthen domestic revenue collection through several measures”. According to the Minister, this decision, effective from 1 July 2016, was based on TRA’s experience in revenue collection and on their existing tax collection systems and coverage across the country. Lessons learned from other countries like Ethiopia and Rwanda were also taken into account (ibid., p. 22, para 32).{7} The Minister emphasised that the decision “reflects the Government’s view that local government authorities did not reach the revenue targets due to inefficient PT collection compared to the available potential” (URT 2016a: 12, para 17). Against the background of the major improvements in PT collection achieved by the MCs after the re-decentralisation in 2014 (Figure 1), this last statement seems imprecise. Following some preparatory arrangements, TRA started collecting PT from 1st October 2016 in 30 municipal councils.

The return of the PT administration to the TRA took the municipalities by surprise. In interviews, municipal staff and representatives from ALAT expressed disappointment and questioned the foundation of the Government’s decision.{8} They argued that the re-centralisation was based neither on an assessment of what the municipalities had achieved with respect to revenue enhancement since early 2014, nor on an assessment of the challenges experienced during the previous period 2008–2014 when TRA collected the property tax.

Trends in property tax collection

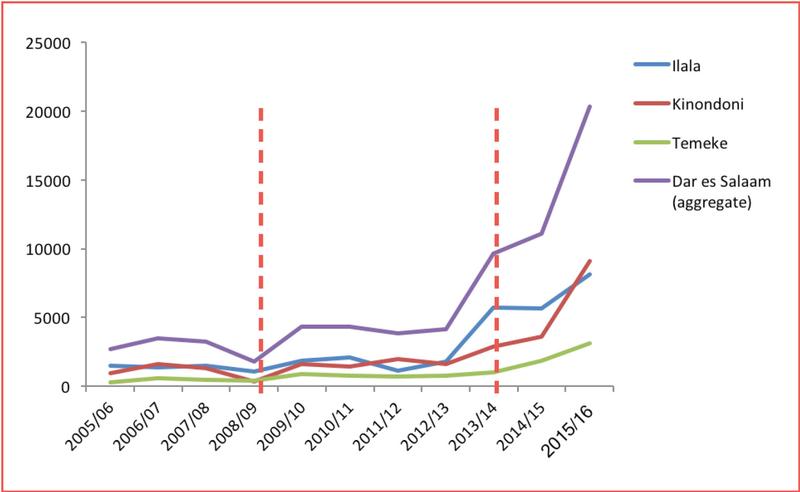

Figure 1 shows the revenue collection performance during the different regimes by drawing the trend in PT revenues in each of the three municipalities in Dar es Salaam in million shillings. In addition, we have included the aggregate graph for Dar es Salaam. The area between the vertical dotted lines depicts the period where PT collection was centralised, from fiscal year 2008/09 until February 2014.

The figure shows some interesting patterns. First, before the centralisation in 2008/09, the revenue collection trend is flat at low collection levels for Ilala and Temeke, and declining for Kinondoni.{9} Second, after centralisation in 2008/09, all three municipalities show a slight increase in revenues in the first year. Thereafter, until 2012/13, PT collection is almost stable for Temeke, but fluctuating in Ilala and Kinondoni. Third, there is an increase in revenue collection for all three municipalities during the end of the centralisation period starting from 2012/13. Fourth, after decentralisation in 2014 there is a sharp increase in revenue collection for all the municipalities, in particular from 2014/15. Data for the fiscal year 2016/17 are not yet available, but based on information from TRA, there has been a major drop in property tax collection.{10}

Revenues from property taxes in Dar es Salaam municipalities, 2005–16 (in million TZS)

Source: Compiled by the authors based on data from the municipalities

How to explain the variation in collection performance over time?

The overarching objective of the PT reform in 2008 was to increase the PT revenues, which was based on an argument by the central government that the municipalities were underperforming. However, the revenue trend during the centralisation of the PT collection after 2008 shows that the increase in revenue collection as anticipated by TRA did not occur (Figure 1). The revenue stayed more or less stable for Temeke and showed a declining trend for Ilala and Kinondoni until 2012/2013 after a slight increase right after the centralisation. An elected councilor in one of the municipalities expressed his frustration about the revenue gain during the centralisation period: “Even though the council was not involved in making the decision, we did not object to the directives from the Prime Minister’s office because we thought that the revenues would increase, which would have been beneficial for the council in terms of financing our planned activities. If only we had known that things would turn to the worse like they are now, we would have objected.”{11}

There were teething problems with the PT collection arrangements which may have contributed to the low revenue performance during the centralisation. Both the municipality and the TRA staff perceived the other part as being non-cooperative. TRA considered the revenue targets set by the MCs’ to be unrealistically high and very difficult to achieve. Nonetheless, TRA’s collection during the first year after centralisation was higher than the municipalities’ the preceding years (Figure 1). The municipality officials were apparently not comfortable with this new arrangement. This was reflected, according to TRA, in the municipalities’ hesitance to share information about taxpayers and by setting high budgetary targets for PT collection without consultations with TRA. The municipalities felt they had been unfairly treated by the Government’s decision to centralise the PT collection. There had been limited prior consultations at the political and bureaucratic levels regarding this arrangement. Local councillors also lost a fair amount of rent seeking opportunities.

In interviews in February 2011, TRA officers involved in authoring the legal amendments and tax officers who were in charge of implementing the reform, explained that consultations and communication between TRA and the municipalities were weak while initiating and rolling out the reform. They argued that consultations might have helped create a broader consensus for the reform and thus avoided future disputes. In this particular case, consultations could have been beneficial for two reasons: First, they could have contributed to broaden ownership of the reform and ensure its sustainability. Second, they could have alleviated apprehensions by municipalities and some foreign donors that the reform was an intentional step taken by the Government to roll back the wider decentralisation initiative.

After the re-decentralisation of the PT collection in February 2014, there has been a dramatic increase in revenue (Figure 1). Within two years after re-decentralisation, Temeke MC increased the PT collection from around TZS 1 billion in 2013/14 to more than TZS 3 billion in 2015/16. The corresponding figures for Kinondoni MC are from TZS 2.8 billion to more than TZS 9 billion, and for Ilala MC from around TZS 5.8 billion in 2013/14 to almost TZS 8.1 billion.

By looking at this trend, one might thus conclude that a decentralised PT administration offers the most promising results. However, this conclusion is premature and is not supported by experiences from the Dar es Salaam municipalities. If decentralisation was the only reason for the sharp increase in revenue collection after 2014, then we would have seen a higher trend in revenue collection before 2008 when PT collection was also decentralised. However, Figure 1 shows that, PT revenue collection was flat and at low levels before centralisation in 2008/09 for Ilala and Temeke and declining for Kinondoni. This indicates that the sharp increase starting from January 2014 may not be due to decentralisation per se, but to a combination of policy and administrative measures at both local and central levels. For example, mass valuation of properties was particularly important after the re-decentralisation in 2014. Arusha City Council was the first LGA to change from a manually administered own-source revenue system to a modern Local Government Revenue Collection Information System (LGRCIS) integrated with a geographic information system (GIS) platform (Lall et al. 2017). The new system was later implemented in other municipalities allowing the local governments to use satellite data to identify taxpayers’ properties. It included an electronic invoicing system that notified and tracked payments. In the first year after the introduction of the new system in Dar es Salaam in 2014/15, more than 270,000 properties had been registered in Kinondoni MC; a huge increase from the 160,000 properties of the old system. In Temeke more than 100,000 additional buildings were registered.{12}

Other factors that are specific to the municipalities may also have played a role. First, the MCs introduced electronic and mobile phone based money payment systems that simplified tax payment and made it more transparent. Kinondoni MC started to use mtaa (street) leaders to notify property owners and collect the tax. Kinondoni also introduced an incentivised system where 14 per cent of the collected PT was returned to the respective wards. Interviews with treasury staff in the municipalities suggest that the motivation to succeed and to collect more than what TRA had managed, was very strong after the re-decentralisation in February 2014.

In addition to policy and administrative measures taken by the municipalities during the re-decentralisation period, some changes that already started during the centralisation period may also have contributed to an increase in revenue starting from 2012/2013. New measures such as investments in infrastructure and new collection methods were introduced by TRA during the centralisation period. The new methods included introduction of tax payment via banks, which reduced the opportunities for corruption due to less direct interaction between taxpayers and collectors. The municipalities continued the bank payment system that was introduced by the TRA during the re-decentralisation period. TRA also piggybacked on collection of PT within their existing block management system. The system consisted of existing TRA teams with additional responsibility for PT collection. These teams were assisted by two revenue collectors from the respective municipalities. This type of on-the-job training was seen as a mechanism for capacity building of municipal staff, in accordance with TRA’s mandate for the intervention.

Data on PT collection for fiscal year 2016/17 is not yet available. However, according to the TRA, there has been a major drop in revenue collection.{13} During the first quarter of the fiscal year, TRA did not collect any PT at all. This hardly reflects ineffectiveness from TRA, but rather inadequate time for preparation and capacity building. Also, the transition period for the handover of collection from the municipalities to the TRA was very short. TRA has established a unit within the Domestic Revenue Department responsible for property tax collection (URT 2017, p. 27, para 39). It has started to develop PT collection procedures and systems. But the unit is severely under-resourced when it comes to staffing and working tools. By May 2017, the legislation regulating TRA’s administration of PT was incomplete. Deadlines for PT payment are partly ruled by local government by-laws, which differ across the country. Property registers have major gaps. According to TRA-staff, between 30 and 50 per cent of the properties in most municipalities are not registered.{14} The opportunity to evaluate and draw lessons from the experiences of the previous period of centralised collection was missed. It is likely that the new PT regime would have benefited from being piloted in a handful of LGAs to assess its viability before the nationwide rollout to 30 municipalities and transfer of full-scale duties to the TRA.

Concluding remarks and policy implications

One of the lessons that can be drawn from our research of the property tax regimes in Tanzania during the last decade, is that effective collection of PT requires constructive working relations between the central government and the municipalities. TRA has been a catalyst for improvements in collection methods at the local level by introducing new digital technologies. TRA has also contributed to reduce the degree to which local elites are able to evade property taxes. However, in contrast to the municipal staff, TRA has limited knowledge about the local PT base. In addition, TRA is not well placed to connect PT compliance with improved local services.

Clarity of the division of functions and responsibilities of the central and local government administrations is essential. It is particularly important to decide which functions are to be centralised and which are to remain the municipalities’ responsibilities. This includes clarifications of responsibility for property registration, valuation, maintenance of property registers and revenue data. It is also essential to assess to what extent local politicians and officials will provide support and cooperate with the national tax administration. This implies clarification of the connection between tax reform and decentralisation policies. If the national government aims to pursue fiscal decentralisation by devolving taxing and spending powers to lower levels of government, a minimum degree of autonomy for sub-national governments over own revenue generation and expenditures is required (Fjeldstad et al. 2017). In April 2017, opposition Members of Parliament criticised the collection of PT by the central Government, saying it had financially “crippled the Development by Devolution (D by D) initiative” (The Citizen, 23 April 2017).{15}

For “centralisation” of PT collection to work requires cooperation, exchange of information and proper coordination between the national revenue administration and the local government authorities. Also other relevant ministries and entities such as the deeds office must be brought in. Thus, in the Budget Speech, delivered 8th June 2017, the Minister of Finance “urge all stakeholders, including property owners, council officials, district commissioners and TRA officials to work hand in hand in fulfilling this important task for development of our communities and the nation at large” (URT 2017: 27, para 40). Mechanisms to improve intra-governmental coordination and cooperation could be established by linking the basic revenue administrative components, including database maintenance, billing and enforcement, with other revenue sources such as business permits, house rents, land rents, and user charges, for instance, water and electricity. Effective policy implementation of such measures requires that the various public agencies develop a mutual understanding of the objectives of the policy and, their respective roles. To ensure a sound working relationship between the actors, it is vital that legislation and standard operating procedures are in place. To make the centralised system work, both the revenue authority and the municipalities must be given incentives to cooperate. This includes measures to compensate the revenue authority for the additional workload, including additional staffing. It also requires modalities for when and how much of the collected revenues to be transferred to the municipalities to secure predictable funding of their activities.

Endnotes

{1} The analysis in this briefing builds on a series of fieldworks undertaken in Tanzania during the last decade until June 2017. The authors have interviewed a wide range of stakeholders, including TRA officers, ministry of finance and municipal staff, representatives of ALAT, business associations, development agencies, and property owners. In addition, we have reviewed tax legislation, budget speeches, reports commissioned by the government and development agencies, and research papers on property taxation in Tanzania.

{2} Promulgated as “The Financial Laws (Miscellaneous Amendments) Act No. 9 of 2008” (URT 2008).

{3} Interviews in the TRA-HQ, Domestic Revenue Department, Dar es Salaam, 2 February 2011.

{4} Interviews with municipal officers in Dar Salaam, October 2014.

{5} Interview with senior manager, Domestic Revenue Department, TRA-HQ, Dar es Salaam, 21 October 2014.

{6} Three acts were amended to empower TRA to be the main collector of the property tax in the country: The Urban Authority (Rating) Act, Cap. 289, R.E 2010; the Local Government Finance Act, Cap. 290; and the Tanzania Revenue Authority Act, Cap. 399. Government Notice No. 276, gazetted on the 30th of September 2016 (URT 2016d), directed TRA to start collecting property tax in 30 municipal councils in Tanzania Mainland. Responsibility for collecting property tax for the rest of the LGAs should remain within the mandate of the respective authorities.

{7} See Fjeldstad et al. (2017).

{8} Interviews in Dar es Salaam, 18 and 20 October 2016.

{9} The financial year in Tanzania runs from 1st July to 30th June.

{10} Interview with TRA officers, Domestic Revenue Department, Dar es Salaam, 9 May 2017.

{11} Interview in Dar es Salaam, 24 June 2011.

{12} Interviews with municipal officers in Kinondoni and Temeke MCs, 19 January 2017

{13} Interview with TRA-officers, Dar es Salaam, 9 May 2017.

{14} Interviews, Domestic Revenue Department, TRA, Dar es Salaam, 9 May 2017.

{15} A main challenge for the municipalities is that they by the end of FY 2016/17 had not received proceeds from property taxes collected by TRA, in spite of the intention of the amended Urban Authorities (Rating) Act, Cap 289 (para 74, sections 2 and 3, p. 95), which states that the revenues collected by TRA “shall be deposited in a special account to be opened by the minister [responsible for LGAs] at the Bank of Tanzania for the benefits of Local Government Authorities” (URT 2016b).

Literature

Ali, M., Fjeldstad, O.-H. and Katera, L. 2017. Property taxation in developing countries. CMI Brief 1: 2017. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute.

The Citizen. 2017 (23 April). TRA property tax collection draws opposition MPs’ ire. http://www.thecitizen.co.tz/News/TRA-property-tax-collection-draws-Opposition-MP [accessed 24 April 2017].

Fjeldstad, O.-H., Ali, M. and Goodfellow, T. 2017. Taxing the urban boom: property taxation in Africa. CMI Insight 1: 2017 (March). Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute.

Fjeldstad, O.-H., Fjeldstad, O.-H., Katera, L. and Ngalewa, E. 2010. Local government finances and financial management in Tanzania: empirical evidence of trends 2000-2007. REPOA Special Paper no. 10-2010. Dar es Salaam: Mkuni na Nyota Publishers.

Fjeldstad, O.-H., Katera, L., Msami, J. and Ngalewa, E. 2009. Outsourcing revenue collection to private agents: experiences from local government authorities in Tanzania. REPOA Special Paper No. 28-2009. Dar es Salaam: Mkuni Na Nyota Publishers.

Fjeldstad, O.-H., Henjewele, F., Mwambe, G., Ngalewa, E. and Nygaard, K. 2004. Local government finances and financial management in Tanzania: Observations from six councils, 2000-2003. REPOA Special Paper no. 16. September 2004. Dar es Salaam: Mkuni na Nyota Publishers.

Lall, S.V., Henderson, J.V. and Venables, A.J. 2017. Africa’s cities. Opening doors to the world. Washington DC: The World Bank.

McCluskey, W. and Franzsen, R. 2005. An evaluation of the property tax in Tanzania: an untapped fiscal resource or administrative headache? Property Management, Vol. 23, No. 1, pp. 45-69.

United Republic of Tanzania [URT]. 2017. Speech by the Minister for Finance and Planning, Hon. Dr Philip I. Mpango (MP), presenting to the National Assembly, the estimates of government revenue and expenditure for 2017/18. Dodoma (8 June).

United Republic of Tanzania [URT]. 2016a. Speech by the Minister for Finance and Planning, Hon. Dr Philip I. Mpango (MP), introducing to the National Assembly, the estimates of government revenue and expenditure for fiscal years 2016/17. Dodoma.

United Republic of Tanzania [URT]. 2016b. Act supplement No 2 to the special Gazette of the United Republic of Tanzania No. 1, Vol 97 dated 30th June, 2016. Dar es Salaam: Government Printer.

United Republic of Tanzania [URT]. 2016c. The Finance Act 2016. Bill supplement to the special Gazette of the United Republic of Tanzania No. 21, Vol 97 dated 17th June, 2016. Dar es Salaam: Government Printer.

United Republic of Tanzania [URT]. 2016d. Subsidiary legislation. Supplement no. 39 to the special Gazette of the United Republic of Tanzania No. 41, Vol 97 dated 30th June, 2016. Government Notice no. 276 (gazetted 30 September), The Urban Authorities (Rating) Act (Cap. 289). Dar es Salaam: Government Printer.

United Republic of Tanzania [URT]. 2008. The Financial Laws (Miscellaneous Amendments) Act No. 9 of 2008. Part II (Cap. 290), Part III (Cap. 399), and Part IV (Cap. 289). Enacted by the Parliament of Tanzania. Dodoma.

United Republic of Tanzania [URT]. 2007. Report of the sub-committee on matters required to be accomplished to enable Tanzania Revenue Authority to collect property rate on behalf of local government authorities in mainland Tanzania (July). Dar es Salaam: Prime Minister’s Office Regional Administration and Local Governments and Tanzania Revenue Authority.

This article is an output from the project Taxing the urban boom in Tanzania: Interests, incentives and real estate in Dar es Salaam and Mtwara. The project is funded by the Norwegian Embassy in Dar es Salaam under the framework agreement between the Embassy and Chr. Michelsen Institute on Development analysis as basis for aid transformation, public debate and policy change. The authors would like to thank Kendra Dupuy, Ingvild Hestad, Jan Isaksen and Ingrid Hoem Sjursen for valuable comments on earlier drafts. Views and conclusions expressed in this CMI Briefing are those of the authors alone.

Odd-Helge Fjeldstad