A brief history of taxation in Uganda: From pre-colonial times to the present

2. Pre-colonial taxation: Centralized and non-centralized political entities

2.1 Taxation and the fiscal system in Buganda

2.2 Comparative assessment of pre-colonial kingdoms

3. The colonial period: Taxation and the British rule

3.1 Indirect rule and the role of chiefs

3.2 The Buganda Agreement of 1900

3.3 Introduction of the Poll Tax and Graduated Personal Tax

3.4 Chiefs as “Decentralized Despots”

3.5 Inter-district variation in tax compliance

4. Post-colonial period: The historical persistence of local taxation

4.1 Enduring relevance of pre-colonial and colonial institutions

4.2 The Graduated Personal Tax (GPT) as a source of revenue and of discontent

4.3 After the abolition of the GPT

5. Continuities and discontinuities in Uganda’s taxation history

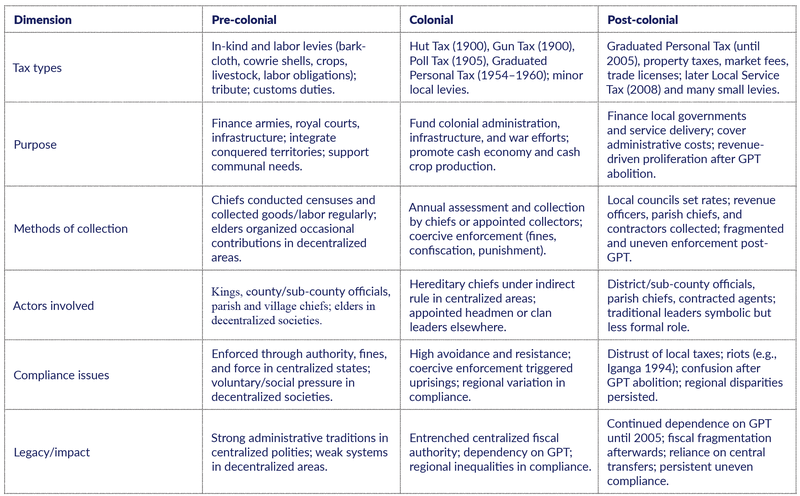

Annex 1: Main features of the tax system in Uganda over time

Pre-colonial taxation: centralized and decentralized political entities

Legacy and impact on the present

The colonial period: taxation and British rule

Legacy and impact on the present

Post-colonial period: persistence and change in local taxation

How to cite this publication:

Odd-Helge Fjeldstad, Godfrey B. Asiimwe (2025). A brief history of taxation in Uganda: From pre-colonial times to the present. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI Working Paper WP 2025:5)

The paper offers a comprehensive and historically grounded analysis of the evolution of Uganda’s tax systems from the pre-colonial period to the present. While existing scholarships have tended to focus on either the colonial or post-independence periods, this study systematically links pre-colonial tribute practices, colonial fiscal transformations, and post-independence local tax reforms to contemporary challenges of revenue mobilization and governance. By tracing both continuities - such as centralized authority, dependence on local intermediaries, and recurrent popular resistance to taxation - the analysis demonstrates how historical legacies continue to shape present-day revenue systems and state-society relations. This long-term perspective not only fills a notable gap in the literature on Uganda’s fiscal history but also offers insights into why certain tax reforms continue to face challenges related to compliance, administrative capacity, and local autonomy. The paper demonstrates that understanding the historical foundations of taxation is essential for designing tax policies that are contextually grounded, politically viable, and responsive to enduring institutional dynamics in Uganda and comparable postcolonial settings.

Acknowledgements

We thank Rebecca Mayanja for excellent documentary and literature research in Uganda, and Monica Kirya, Mette Kjær and Ingrid Hoem Sjursen for valuable comments on earlier drafts. The paper was prepared with financial support from the Research Council of Norway (302685/H30). Points of view and possible errors are entirely our responsibility.

About the authors

Odd-Helge Fjeldstad

Chr. Michelsen Institute, Bergen, Norway; and African Tax Institute, Department of Economics, University of Pretoria, South Africa. E-mail: odd.fjeldstad@cmi.no

Godfrey B. Asiimwe

Department of Development Studies, Makerere University, Kampala; and Department of Humanities, Mountains of the Moon University, Fort-Portal, Uganda. E-mail:

god.asiimwe@gmail.com

1. Introduction

Taxation has been a defining feature of governance, economic organization, and state-building in Uganda from the tribute systems of the centralized pre-colonial polities to the contemporary challenges of local government finances (Ssekamwa, 1970; Tuck, 2006; Kjær, 2009; Bandyopadhyay and Green, 2016; Ali and Fjeldstad, 2023). Over time, tax systems have both reflected and influenced shifts in political authority, economic priorities, and administrative capacity (Mamdami, 1996; Englebert, 2000; Reid, 2017; Taylor, 2023).

This paper examines the historical evolution of taxation in Uganda, tracing its development from pre-colonial tribute systems, through colonial impositions such as the Hut Tax and Graduated Personal Tax (GPT), to post-independence reforms and contemporary local government tax practices. It analyzes how these historical arrangements have shaped present-day fiscal policies, tax administration, and governance structures, with a particular focus on the persistence of institutional legacies and their implications for local government autonomy. By connecting past and present, the study offers a historically grounded perspective that can inform ongoing policy debates on building a more effective, equitable, and sustainable tax system in Uganda.

Drawing on historical records, official reports and existing scholarship, supplemented by the authors’ own research on taxation in Uganda and other African contexts, the analysis compares tax types, collection methods, purposes, and compliance mechanisms across different historical periods. The comparative approach highlights how institutional patterns have persisted, adapted, or been disrupted over time. By examining these historical shifts, this paper contributes to the broader discourse on fiscal policy, governance, and local taxation in Uganda. It highlights the persistence of historical tax structures and their enduring influence on contemporary tax administration. The study also sheds light on the challenges faced by current local governments in mobilizing revenue, ensuring tax compliance, and balancing fiscal decentralization with central government control.

The paper contributes to the literature on taxation and state formation in Africa by offering a comprehensive and historically grounded analysis of the evolution of Uganda’s tax systems from the pre-colonial period to the present. While existing scholarships have tended to focus on either the colonial or post-independence periods, this study systematically links pre-colonial tribute practices, colonial fiscal transformations, and post-independence local tax reforms to contemporary challenges of revenue mobilization and governance. By tracing both continuities – such as centralized authority, dependence on local intermediaries, and recurrent popular resistance to taxation – the analysis demonstrates how historical legacies continue to shape present-day revenue systems and state-society relations. This long-term perspective not only fills a notable gap in the literature on Uganda’s fiscal history but also offers insights into why certain tax reforms continue to face challenges related to compliance, administrative capacity, and local autonomy. Ultimately, the paper’s contribution lies in demonstrating that understanding the historical foundations of taxation is essential for designing tax policies that are contextually grounded, politically viable, and responsive to enduring institutional dynamics in Uganda and comparable postcolonial settings.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: Section 2 examines systems of taxation in pre-colonial Uganda, distinguishing between centralized and decentralized societies. Section 3 analyzes the colonial tax regime and its implications for governance and local administration. Section 4 discusses post-independence local government tax policies, reforms, and the constraints they have faced. Building on this analysis, Section 5 highlights the continuities and discontinuities in Uganda’s taxation history. Section 6 concludes. Annex 1 provides a summary of the main features of Uganda’s tax system over time.

2. Pre-colonial taxation: Centralized and non-centralized political entities

In pre-colonial Uganda, taxation practices varied widely across the country’s diverse political systems (Bandyopadhyay and Green, 2016). In the south and west, the centralized kingdoms Buganda, Bunyoro, Toro, Nkore, and Mpororo developed hierarchical administrations headed by kings who exercised executive, judicial, legislative, and spiritual authority (Doornbos, 1975; Karugire, 1996). Bunyoro was one of the most powerful kingdoms in Central and East Africa from the 13th century, maintaining regional dominance for centuries. Over time, however, shifts in trade patterns, internal succession struggles, and the growing assertiveness of neighboring states gradually weakened its dominance. In 1830, Toro broke away as a separate kingdom, further weakening Bunyoro’s position. By the latter half of the 18th century, Buganda had expanded and consolidated its power to the point of surpassing Bunyoro in both size and influence (Uzoigwe, 1973; Muhangi, 2015). Busoga, located in the east, did not exist as a unified political entity before colonization, but was created by the British through the amalgamation of several smaller principalities (Nayenga, 1981). In the west, however, the kingdom of Nkore was a long-established centralized monarchy (Doornbos, 1975; Karugire, 1971, 1996).

Source: Ali and Fjeldstad (2023), based on Murdock’s Ethnographic Atlas (1967)

In contrast, the eastern and northern parts of Uganda – home to groups such as the Bugisu, Teso, and Karamoja in the east, and Acholi, and Lango in the north – were organized in a multitude of smaller, often fragmented political entities, often lacking any centralized political administrative unit above the village level (Muhangi, 2015). In parts of Eastern Uganda, such as Bukedi, Bugisu and Teso, political authority was vested in village heads or councils of elders, and no formal centralized tax systems existed (Muhangi, 2015; Gennaioli and Rainer, 2007). Among the Karamajong in the north-east, political and military activity were structured around the age set-system, with decision-making and adjudication carried out by a council of elders. In the northern areas, such as Acholi and Lango, communities were organized into small chiefdoms. Political leaders in both Eastern and Northern Uganda were essentially “leaders among equals”, with their decisions subject to scrutiny by the council of elders or village leaders. Overall, these regions lacked centralized administrative units with formal tax systems in the pre-colonial times (Kjær, 2009).

The centralized kingdoms were characterized by strong bureaucratic systems that extended from the King down to the village chief. Political authority was vested in the King, whose position was hereditary (Farelius, 2012). He exercised executive, judicial, legislative, and spiritual powers, and his word was held in the highest regard “almost equated to the word from God” (Muhangi, 2015: 105). The king was assisted in administrative matters by provincial chiefs and a council of notables, including clan heads. As commander-in-chief of the armed forces, the King maintained overall control of the military, while each provincial chief commanded a detachment stationed in his province. At the clan and village levels, adjudication and enforcement of customary rules were undertaken by clan heads and chiefs. Appointed by the King, the chiefs were responsible for tax collection and for mobilizing the King’s subjects for village courts, communal labor and other public services (Ray, 1991). Revenue derived both from taxes on the local population and from tributes extracted from subordinate or tributary states, thereby reinforcing both the economic base and the political authority of the centralized kingdoms.

2.1 Taxation and the fiscal system in Buganda

The most extensive documentation of taxation in pre-colonial Uganda refers to the Buganda Kingdom. Emerging in the 15th century as a relatively small polity comprising only a few counties (Ssekanwa, 1970: 1), Buganda gradually expanded into a powerful kingdom. Its capacity to institutionalize systems of taxation and organize labor played a crucial role in this rapid growth and consolidation. By effectively channeling resources from both internal taxation and external tribute, the kingdom managed to sustain a centralized bureaucracy, strengthen its military capacity, and consolidate authority over increasingly vast territories. By the latter part of the 18th century Buganda had developed into one of the most powerful kingdoms in Central and East Africa (Kiwanuka, 1971; Uzoigwe, 1973). This trajectory underscores the central role of bureaucratic organization and fiscal systems in facilitating state expansion and regional dominance.

Tax revenues in the Buganda Kingdom served multiple functions, including sustaining the army, financing the royal court, and supporting the administration of newly conquered territories (Ssekamwa, 1970). A significant portion of these revenues was also allocated to support the royal court and to cover the costs of frequent banquets, known as okugabula Obuganda (Ssekanwa 1970, 5-6). These banquets were not merely ceremonial; they performed crucial political functions. The banquets provided the monarch with opportunities to gauge political opinion, monitor potential dissent, particularly among chiefs, test the popularity of leaders within their constituencies, and secure their loyalty through displays of royal generosity. From the second half of the 17th century, the Kabakas expanded Buganda’s territory substantially. This expansion heightened the demand for revenue to sustain military campaigns and to govern newly conquered regions. Administrative posts in these territories became instruments of royal patronage, distributed by the Kabakas to loyal supporters. In this way, taxation and patronage were intertwined, serving both as mechanisms of state consolidation and as tools for managing elite competition with the kingdom.

In the centralized kingdoms, taxation was imposed on the kingdom’s subjects, while tributary states were obliged to provide regular tribute (Ali and Fjeldstad, 2023). Generally, women and unmarried men did not pay tax. In Buganda, the taxes levied on the population can be divided into four main categories (Reid, 2002; Ssekamwa, 1970), each of which served not only an economic function but also reinforced the political and administrative consolidation of the kingdom.

The first was a compulsory household tax paid by every married man who owned a homestead, usually in the form of bark cloths and cowrie shells. This tax was central to social regulation, as it tied fiscal responsibility to marriage and household ownership, thereby reinforcing patriarchal authority and the integration of domestic units into the state.

The second was a kind of excise duty levied on a range of agricultural and manufactured goods, including food crops, livestock such as cattle and goats, alcoholic beverages, and manufactured goods such as baskets and carpets. This form of taxation functioned as a mechanism of economic regulation, ensuring that surplus production and trade directly supported the kingdom. By extracting value from both subsistence and artisanal economies, the Kabaka consolidated control over local production while binding producers more tightly to the central state.

The third category consisted of customs duties imposed on goods exchanged across Buganda’s borders with neighboring polities, particularly commodities like salt and iron tools traded with Bunyoro. These levies reflect Buganda’s increasing involvement in regional trade and its assertion of sovereignty over commercial exchanges. Control of border trade not only generated revenue but also symbolized Buganda’s growing regional influence and capacity to regulate cross-polity interactions.

The fourth was a military exemption levy. From at least the second half of the 17th century, military service had become a formal obligation for all able-bodied men. However, those unwilling or unable to serve could pay a levy in lieu of participation. This system simultaneously reinforced Buganda’s militarization by ensuring that armies remained large and well-supported, while monetizing non-participation, thus converting individual resistance into another source of royal revenue.

Another source of revenue for the Kabakas came from fines imposed on chiefs who failed to fulfill their administrative duties. In the pre-colonial period, such fines were levied as penalties for negligence, serving both as a punitive measure and as a mechanism to secure the accountability and commitment of local administrators (Ssekamwa, 1970).

Taken together, these taxes and fines served as more than mere instruments of revenue collection. They functioned as pillars of Buganda’s state-building strategy: embedding households into state structures, regulating economic activity, projecting authority over regional trade, and sustaining a militarized polity. Through this multifaceted fiscal system, the Kabakas transformed taxation into a key tool of governance, legitimacy, and expansion.

In addition to the main types of taxes, all able-bodied men in Buganda were obliged to provide unpaid labor to the chiefs for a specified period, a practice known as luwalo. This obligation functioned as a form of in-kind taxation, with labor contributions typically directed toward public works such as constructing and maintaining roads, as well as building enclosures and residences for the chiefs (Reid, 2002). Although this labor was not directly compensated, chiefs often rewarded participants indirectly by hosting communal feasts, thereby reinforcing ties of reciprocity and loyalty between rulers and their subjects.

Beyond its immediate economic utility, luwalo played a critical role in Buganda’s broader political economy. First, it enabled the kingdom to mobilize large pools of labor without incurring direct fiscal costs, ensuring that infrastructure and administrative centers could be maintained efficiently. Second, the system tied local communities to the authority of chiefs, embedding households into the political hierarchy and normalizing the expectation of service to the state. Third, by channeling labor through chiefs – who in turn redistributed food and hospitality – the Kabaka strengthened patron-client networks that underpinned elite loyalty. Finally, the capacity to mobilize mass labor for both economic and military purposes enhanced Buganda’s cohesion and facilitated its territorial expansion, as roads and infrastructure were essential to sustaining military campaigns and administering newly conquered areas. Thus, luwalo was not merely a form of unpaid labor; it was a mechanism through which the Kabaka integrated taxation, labor mobilization, and patronage into a unified system of governance. By converting labor obligations into political capital, the monarchy sustained both its administrative apparatus and its legitimacy, making luwalo a cornerstone of Buganda’s state-building strategy.

The royal treasury also benefited from a share of the booty obtained during wars. The Buganda Kingdom frequently engaged in military campaigns against neighboring polities, particularly the Kingdom of Bunyoro-Kitara. From the second half of the 17th century onward, Buganda’s armies often returned with slaves, ivory, livestock and other valuable commodities. A significant portion of these spoils was claimed by the Kabaka, thereby strengthening his economic base and political authority (Ssekamwa, 1970).

Tribute from subordinate states was in periods another important source of revenue for the kingdoms. However, collecting it was at times not easy (Roscoe, 1911). When chiefs in tributary territories refused to deliver tribute voluntarily, the king was often compelled to enforce payment through military action. This was the case, for instance, during conflicts between Buganda and the autonomous chiefs in Busoga, where many battles were fought over the demand for tribute (ibid.).

In the early period of Buganda’s fiscal administration, there was no fixed schedule for tax payment. Instead, taxes were collected whenever the King deemed it necessary (Reid, 2002). By the 19th century, however, Buganda had developed a more systematic system of tax collection, where taxes were levied twice annually. Tax collection was conducted in a decentralized manner, whereby village chiefs implemented a census of nearly every household to determine ownership of property and resources (Reid, 2002; Ali and Fjeldstad, 2023). All contributions made by the populace to the Kabaka were regarded as tax, known as Omusolo gwa Kabaka (“the Kabaka’s tax”, which was deposited in the Enkuluze – the Royal Treasury). According to Ssekamwa (1970: 10), “the collection of taxes had reached a high standard of efficiency and that both the people at the top and the collectors were keen on seeing that taxes were collected and that they reached the Kabaka”.

The persistence of these extractive mechanisms must be contextualized within Buganda’s broader socio-economic structure. As Buganda developed into a highly centralized political entity, its administrative and fiscal systems became increasingly institutionalized. Such efficiency was enabled by Buganda’s high degree of political centralization. Chiefs at multiple levels were held accountable for ensuring that revenue reached the Kabaka, creating a culture of administrative discipline and compliance (Ali and Fjeldstad, 2023). Moreover, the Kabaka’s practice of redistributing portions of collected revenue to loyal chiefs reinforced political loyalty and further strengthened the system’s durability. In this sense, Buganda’s fiscal regime exemplified a sophisticated pre-colonial bureaucracy that provided a foundation for state legitimacy and enduring norms of tax compliance.

2.2 Comparative assessment of pre-colonial kingdoms

Buganda was distinguished from other kingdoms in the Great Lakes region by the degree of its institutionalized efficiency. Below we briefly examine the tax systems of two other kingdoms – Bunyoro and Ankole. These cases are selected because they represent two of the most historically significant pre-colonial polities in Uganda, each characterized by distinct political and fiscal structures. A comparative analysis of these kingdoms, alongside Buganda, helps to elucidate how varying levels of political centralization, social stratification, and economic organization influenced the evolution of taxation and state capacity in the region.

Bunyoro

Bunyoro’s taxation system was far less systematic than Buganda’s and more closely tied to its military and political fortunes. The Omukama (the King) of Bunyoro extracted revenue primarily through tribute and plunder obtained in warfare. Tribute typically consisted of livestock, agricultural produce, iron goods, and labor contributions, and it was imposed upon subordinate chiefs and conquered territories (Beattie, 1960). Known for its salt production, Bunyoro also levied an in-kind tax on salt purchased (Good, 1972).

Unlike Buganda’s practice of conducting household censuses, Bunyoro’s taxation system operated largely on an ad hoc basis. Tribute obligations varied depending on the kingdom’s military campaigns and the strength of the Omukama’s authority at any given time. In periods of weakness, tributary chiefs often withheld payments, forcing the monarchy to rely on coercion or accept the loss of revenue. This volatility reflected the kingdom’s fragmented political structure, in which local chiefs enjoyed a greater degree of autonomy than their Buganda counterparts (Reid, 2002).

Bunyoro’s reliance on tribute was not entirely ineffective. In times of political strength, especially under powerful rulers such as Kabalega in the late nineteenth century, tribute became a significant source of revenue, reinforcing the military’s capacity and enabling resistance against external encroachment, including British colonial expansion (Beattie, 1960). However, the absence of systematic, routine taxation limited Bunyoro’s fiscal efficiency relative to Buganda and ultimately contributed to its diminished status in the region. Bunyoro’s relative decline in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries weakened its capacity to maintain consistent revenue flows. The loss of territory and political influence to Buganda, coupled with internal succession disputes, eroded the kingdom’s administrative stability (Nyakatura, 1973).

Ankole

Ankole’s fiscal system, while distinct from both Buganda and Bunyoro, reflected the predominance of pastoralism in its economy (Roscoe, 1923). The Omugabe (the King) derived his primary revenues from cattle tribute, as cattle were both the principal form of wealth and a marker of political authority (Karugire, 1980). Unlike Buganda’s diversified tax base, which included agricultural produce and labor, taxation in Ankole was narrowly concentrated on livestock. This reliance on a single economic resource created vulnerabilities but also reinforced the centrality of cattle in Ankole’s socio-political order.

Taxation in Ankole was irregular and often tied to ceremonial events or the immediate needs of the royal household. Tribute was commonly extracted during royal rituals, succession ceremonies, or military mobilizations (Reid, 2002). Chiefs played a role in mobilizing cattle for the Omugabe, but the process was far less bureaucratic than in Buganda. There was little evidence of systematic household censuses or biannual levies. Instead, taxation functioned as a symbolic reaffirmation of loyalty to the monarchy, with tributary chiefs and pastoral clans contributing cattle in recognition of the Omugabe’s authority (Karugire, 1980). While the symbolic and ritualistic dimensions of taxation strengthened the cultural legitimacy of the Omugabe, the absence of regularized, diversified revenue streams restricted Ankole’s capacity for sustained political expansion or large-scale military organization. Compared to Buganda’s sophisticated fiscal machinery, Ankole’s taxation system was less efficient, more dependent on social norms of deference, and ultimately less adaptable to the demands of nineteenth-century regional competition.

Comparative assessment

A comparison of Buganda, Bunyoro, and Ankole reveals significant variations in fiscal capacity, closely tied to broader differences in political centralization and economic foundations. Buganda distinguished itself by institutionalizing a regularized, biannual taxation system supported by decentralized census-taking and a diversified tax base. This system not only ensured revenue stability but also reinforced the Kabaka’s authority through administrative accountability and redistribution.

By contrast, Bunyoro’s system was more volatile, reliant on tribute tied to military power and political dominance. While tribute could be a substantial revenue source in times of strength, the kingdom’s internal instability and declining regional influence undermined fiscal regularity and efficiency. Ankole, meanwhile, reflected the constraints of a pastoral economy, with taxation narrowly centered on cattle tribute and lacking bureaucratic routinization.

Ultimately, Buganda’s comparative advantage in fiscal organization contributed to its ascendancy in the nineteenth century, enabling both internal consolidation and external expansion. Its administrative efficiency provided not only material wealth but also enduring institutional legacies, as recent research demonstrates that pre-colonial centralization fostered persistent norms of tax compliance in Buganda’s former territories (Ali and Fjeldstad, 2023).

2.3 Summary

While pre-colonial Uganda displayed remarkable diversity in fiscal organization, the advent of British colonial rule reshaped taxation. The British built upon existing systems of centralized kingdoms, particularly Buganda, while imposing new taxes such as the Hut Tax and Poll Tax. At the same time, in non-centralized regions, colonial administrators invented new chieftainships to facilitate tax collection. These continuities and ruptures set the stage for Uganda’s colonial fiscal order which is the focus of Section 3.

3. The colonial period: Taxation and the British rule

Uganda was colonized by Britain between 1890 and 1910, and British rule lasted until independence in 1962. This period was characterized by a strong continuity of pre-colonial institutions (Apter, 1961; Pratt, 1965; Gennaioli and Rainer, 2007). The British colonizers recognized the importance of native authorities for implementing their policies and maintained local ethnic identities through the policy of indirect rule (Kjær, 2009; Bandyopadhyay and Green, 2016; Ali et al., 2020).

3.1 Indirect rule and the role of chiefs

In the traditional centralized kingdoms, such as Buganda, Bunyoro, Toro and Ankole, the British largely maintained the pre-colonial hierarchy of chiefs (Apter, 1961, cited in Gennaioli and Rainer, 2007: 188). Chiefs were relied upon to build roads, organize schools, improve sanitation, and perform other administrative duties (Pratt, 1965). They also oversaw tax collection and retained a share of the revenue (Mamdani, 1996; Tuck, 2006). In return for their collaboration, chiefs gained greater autonomy in areas such as land allocation and rent distribution (Kjær, 2009; Ali et al., 2020).

In traditionally stateless or fragmented districts, such as Lango or Teso, the British appointed chiefs from among village headmen and clan leaders. Due to the scarcity of British officers, these chiefs enjoyed considerable unsupervised power, as they were accountable only to distant colonial administrators (Low, 1965). This often led to exploitation of people in their areas (Gennaioli and Rainer, 2007). Burke (1964: 37) describes this “effective but completely autocratic chieftainship”, contrasting sharply with the more accountable systems in the kingdoms where the chiefs were restrained by the accountability of traditional authority. The greater accountability of local chiefs in the traditionally centralized areas is also documented by other scholars (e.g., Apter, 1961; and Richards, 1960). For example, in Buganda local chiefs could be quickly dismissed by the Kabaka or other senior traditional authorities if their performance was unsatisfactory (Low, 1971). Since political authority in Buganda was closely tied to taxation, tax collection became an important performance measure for chiefs.

3.2 The Buganda Agreement of 1900

In 1899, Harry Johnston was appointed Special Commissioner to reorganize the administration of the British Protectorate after the suppression of the mutiny of the Sudanese soldiers and to end an ongoing war with the kingdom of Bunyoro in Western Uganda (Ssekamwa, 1970). The Buganda Agreement of 1900, incorporated Buganda as a province of the Protectorate, transforming it into a constitutional monarchy where power shifted from the Kabaka to the Lukiiko, the Kings’ advisory council (Reid, 2017: 158–160). During the negotiations leading to the Agreement, Buganda’s negotiators demanded retention of some taxation powers. Johnston conceded, writing to Lord Salisbury, the Colonial Secretary of State, that taxation was integral part of the Buganda’s political philosophy, and that denying it risked rebellion (Ssekamwa, 1970: 1).

The continuation of the Buganda Treasury within the British Protectorate reminded the people that taxes would remain and that the power of Buganda had not been taken completely over by the British. Although Buganda retained a treasury, its sources of revenue – market dues, court fees, and fines – were limited. The main taxes introduced in 1900, the Hut Tax (levied on every male hut owner) and the Gun Tax (on gun owners), went to the Protectorate Government in Kampala. The British colonial government hoped that doing so would devise a way of making the natives contribute towards the running of the colonial administration. Wars against the kingdoms of Bunyoro and Buganda and the suppression of the Sudanese Mutiny in the late 1890s had placed a heavy burden on the British administration’s expenses (Low, 2009; Furley, 1959). To appease Buganda’s chiefs, Johnston allocated 10% of these revenues to cover the Kabaka’s and chiefs’ salaries (Ssekamwa, 1970: 33). However, avoidance of the Hut Tax reduced revenues to the Buganda Treasury. For instance, families consolidated into single huts during tax collection to evade liability. Others fled from Buganda to provinces with weaker enforcement. Court fees and fines thus became Buganda’s most reliable income.

The regents oversaw revenues carefully, funding courthouses, police, parish chiefs, and administrative supplies (Ssekamwa, 1970: 40). Mismanagement threatened both service delivery and increased British interference in the financial affairs of the kingdom. For example, in 1904 the British Chief Justice attempted to seize Buganda’s court fees, but the regents strongly resisted claiming that it intended to ruin the Buganda administration (ibid., 41). Native local authorities first secured independent taxation powers in 1925, when compulsory labor obligations (luwalo) were commuted into cash payments.

3.3 Introduction of the Poll Tax and Graduated Personal Tax

The Poll Tax, introduced in 1905, marked a turning point in colonial taxation (Fjeldstad and Therkildsen, 2008). Initially it was levied on all adult males at a flat rate. Non-Africans were not taxed until 1919 when a poll tax was introduced for them. In the 1950s it was replaced by the Graduated Personal Tax (GPT), modestly graduated according to assessed income of the individual taxpayers (Davey, 1974: 35-38). The GPT applied to all able-bodied men over the age of 18, while women (unless employed), the elderly, and the very poor were exempted (Bakibinga et al., 2018). In practice, however, enforcement was coercive, involving forceful confrontations between taxpayers and collectors (Fjeldstad and Therkildsen, 2008). This generated widespread resentment and riots, and the GPT came to symbolize colonial oppression.

The objectives of the poll tax evolved substantially over the course of the colonial period, reflecting shifting administrative and economic priorities. As Fjeldstad and Therkildsen (2008: 115) observe, the tax served multiple and sometimes overlapping purposes. Initially, it was designed to compel subsistence farmers into wage labor or cash-crop production for export, thereby integrating local economies into the colonial market system. During the war years, particularly World War II, the poll tax became an important mechanism for financing Britain’s war efforts. In the post-war period, its rationale expanded further to support the goal of making the colony financially self-sufficient, reducing dependence on customs duties – the other main source of colonial revenue. Eventually, the tax also came to be justified as a means of funding development projects and maintaining the colonial administrative apparatus.

Taxation also aimed to integrate rural Africans into the cash economy, initially by compelling them to grow cotton. Until the beginning of World War II, the colonial administrators resisted levying income tax on non-natives – that is, European settlers, Asian traders, and other non-African residents – who were considered essential to the functioning of the colonial economy. At the same time, they were reluctant to further increase the already heavy poll taxes imposed on Africans, which had become a major source of resentment and economic pressure in rural areas. The British Governor argued that their spending power was needed to enhance cash crop production (Thompson, 2003:125). However, London overruled these concerns during the war, ordering higher direct taxation across all groups of taxpayers while freezing local expenditures (ibid. 117-121). The aim was additional tax revenues to fight the Empire’s war elsewhere This echoed the historic European link between taxation and warfare (Tilly, 1990).

3.4 Chiefs as “Decentralized Despots”

The role of the chiefs changed substantially under colonial rule (Bandyopadhyay and Green, 2016). Increasingly, they became less accountable to the people and more beholden to the British. In the terms of Mamdani (1996), chiefs became “decentralized despots”. This was most noticeable in non-centralized areas where new chiefdoms were created, but even in kingdoms chiefs gradually lost legitimacy as they came to be seen as colonial agents, making it hard for them to command respect and to govern (Ssekamwa, 1970: 79)

Resistance was widespread. In the Nyangire Rebellion of 1907 in Bunyoro, the Banyoro refused to obey Baganda chiefs, did not pay taxes, and rejected orders from colonial administrators. Later, the Bunyoro Tax Riot of 1927 reflected similar tensions. Although this riot is not well-documented in readily available historical records, there is a wealth of scholarly literature that examines the broader context of colonial taxation and resistance in Bunyoro during the early 20th century (Jamal, 1978; Otunnu, 2016). In Buganda, riots erupted in 1945 and 1949, and in 1960 the Bukedi riots culminated in the killing of chiefly agents of the British (Ingram, 1994; West, 2012). Mounting unrest forced the British to replace unpopular chiefs before independence in 1962 (Bandyopadhyay and Green, 2016). The transfer of power from chiefs to elected politicians in the district administrations, which began in 1955, gave councils the power to tax (Constitutional Review Commission 2003:106). While intended to strengthen participatory governance and fiscal autonomy, this shift destabilized established structures of authority, generating tensions and administrative fragility in several districts, most notably in eastern Uganda.

3.5 Inter-district variation in tax compliance

Tax compliance varied substantially across regions (Davey, 1974). In 1958, 85% of adult males in Ankole in the west paid the poll tax, compared to only 58% in Acholi district in the north (Fjeldstad and Therkildsen, 2008: 127). A decade later, payments had declined everywhere, but most sharply in eastern districts such as Bugisu and Busoga, where colonial supervision of chiefs and councils had been strictest. Once coercion ceased, compliance collapsed.

In western districts, where the colonial administration was much less direct and obtrusive, respect for chiefly authority sustained higher poll tax payments even after independence. In the north, where colonial enforcement had always been weak, declines were modest (Davey, 1974: 141–142).

3.6 Summary

The colonial period in Uganda was marked by a tension between continuity and transformation. British rule relied heavily on pre-colonial institutions, particularly the authority of chiefs, yet reshaped their roles to serve colonial interests. Taxation became both a tool of administration and a source of deep contestation. While Hut Tax, Gun Tax, and later the Poll and Graduated Personal Taxes expanded the fiscal base of the Protectorate, and their coercive enforcement generated widespread resistance and resentment. Chiefs, once accountable to their kings and communities, increasingly became agents of the colonial state – what Mamdani (1996) terms “decentralized despots” – and in many cases lost legitimacy. At the same time, tax compliance varied across regions, sustained in some areas by chiefly authority but collapsing where colonial enforcement had been most coercive. Together, these dynamics reveal how taxation under British rule simultaneously entrenched continuity with pre-colonial structures while fundamentally altering the political economy of authority and accountability in Uganda.

World War II transformed political consciousness in Uganda. About 77,000 Ugandan men were enlisted in the British armed forces, many of whom became politically active upon their return. As Thompson (2003:5) observes: Before 1939, the colonial state was favoured by the modesty of its goals and by the relatively co-operative African societies. The war changed all this. From the 1940s onward, relations with the colonial regime became increasingly conflictual, culminating in independence in 1962.

4. Post-colonial period: The historical persistence of local taxation

The legacy of pre-colonial and colonial taxation profoundly shaped Uganda’s fiscal and political landscape after independence in 1962. Reliance on coercive poll taxes, the central role of chiefs in revenue collection, and persistent regional disparities in tax compliance left deep structural imprints. At the same time, independence introduced new pressures: financing a modern state, reducing dependence on colonial-era institutions, and responding to rising political demands for improved public services. In this context, post-independence taxation embodied both continuity with historical practices and new reform efforts, as successive governments sought to consolidate authority and mobilize domestic resources.

4.1 Enduring relevance of pre-colonial and colonial institutions

Pre-colonial and colonial institutions have remained influential in Uganda long after independence (Englebert, 2002). Although kingdoms were abolished in 1966 and further fragmented into smaller local government units after the end of the civil war in 1986, traditional institutions remained central to ethnic belonging and social cohesion (Englebert, 2002; Reid, 2017). Attempts to separate politics from culture and limit the activities of traditional leaders were only partially successful. Kingship continued to embody legitimacy in the absence of alternative sources of cultural and political authority. As Reid (2017: 345) notes: “kings had proven durable and ‘history’ continued to hold out against ‘modernity’ – for many of the same reasons across the colonial and post-colonial periods, namely that they have flourished in the absence of an alternative political and cultural source of power”. Chiefs, though no longer tax collectors, retained influence as intermediaries between the state and citizens through civic activities such as health, education and environmental initiatives (Reid, 2017).

Relations between traditional kingdoms and the national government have remained contentious. Buganda’s historically privileged status under colonial rule created long-standing tensions with other regions. Its push for autonomy has often been echoed by smaller kingdoms in the west and by Busoga in the east (Davey, 1974; Kasfir, 2019; Asiimwe, 2022). During the upheavals of the Milton Obote (1966-71 and 1980-85) and Idi Amin (1971-79) regimes, the kingdoms’ political privileges were reduced. The National Resistance Movement’s (NRM’s) decentralization reforms since the 1990s have simultaneously consolidated central authority over key national issues while allowing district authorities relative autonomy (Crook, 2003; Fjeldstad and Therkildsen, 2008). Yet, in more centralized pre-colonial states, the power to tax is still viewed as essential to autonomy. As one Buganda official lamented in 2002: We cannot celebrate the restoration of the monarchy when our King does not have political authority, when he does not have the power to collect taxes and he depends on handouts from good Samaritans for a living (New Vision, Kampala, 29 May 2002, quoted in Johannessen, 2006: 6,note 6). This reflects broader findings that historically centralized groups remain better able to coordinate political demands and sustain autonomous institutions (Gennaioli and Rainer, 2007; Kjær, 2009). Having had traditions for centralized rule with centrally coordinated tax collection may leave path dependencies that reinforce present attempts to upkeep administrative autonomy (Kjær, 2009: 229). In contrast, less centralized groups have more fragmented political leadership, and thus are less actively engaged in the demand for more autonomy.

4.2 The Graduated Personal Tax (GPT) as a source of revenue and of discontent

The GPT became one of the most visible points of state-society tension. Discriminatory assessments and rising rates fueled rural resistance (Davey, 1974; GoU, 1987). Mamdani (1991:354) links peasant rebellion against the Obote II regime in the mid-1980s directly to aggressive GPT enforcement, which helped bringing the NRM – led by Yoweri Museveni – to power in 1986. Yet, discontent persisted. For instance, riots in Iganga district in 1994 were motivated by unfair assessment of the GPT (GoU, 1994). Since then, there has been no GPT assessment in this district (Kjær, 2004: 28).

Geographical differences in poll tax compliance became increasingly pronounced in the post-independence period. Livingstone and Charlton (1998: Table 6) found that in 1993 the proportion of taxpayers relative to eligible men aged 20–59 ranged from 96% in Mpigi district (central region) to only 4% in Kitgum (northern region). Even within the central region, which recorded the highest overall proportions of taxpayers, notable exceptions existed: in Rakai district, for instance, only 29% of the eligible male population paid the tax, compared to a regional average of 76%. Both the eastern and northern regions of Uganda continued to register below-average compliance, much as they had prior to independence.

Nationwide surveys confirm widespread dissatisfaction with GPT collection. A survey of 36 communities conducted by the Ministry of Finance in 1998, found that respondents believed that tax collection was fairer in the 1960s than at the time of the survey. The report notes that “the poor are burdened while the rich are left virtually untouched”, and respondents frequently complained of “coercion, threats, and confiscation by collectors”, often followed by bribes to recover seized property (UPPA, 2000:111–12). A follow-up survey in 2002 similarly found that “[b]rutal graduated tax collection methods are noted with resentment … and reported to be a reason for unwillingness to pay” (UPPA, 2002: xvi). For example, in Mwera parish in central Uganda most casual workers reportedly avoided travelling beyond their parishes for fear of arrest as tax defaulters (ibid.:75). The 2002 survey identified the GPT as a more serious and widespread grievance than in 1998, underscoring its growing status as a political liability. Crucially, GPT revenues – initially justified as a development levy – were increasingly diverted to administrative expenses by the 1990s (Bahiigwa et al., 2004), further eroding legitimacy.

Some district authorities relied almost entirely on central government transfers, while others managed to raise considerable amounts on their own. In addition, local governments are authorized to levy various other taxes and fees, such as trade licenses, property taxes, market fees, garbage collection fees and road user fees (Bakibinga et al., 2018). With the exception of property taxes, which hold potential to generate substantial revenues in municipalities, most other taxes and fees contribute marginally to sub-national governments’ own-source revenues.

Between independence and its abolition in 2005, the GPT was the principal source of local government own revenue, although collection capacity varied across districts (Kjær, 2009). In the 1960s, some revenues were indeed used for local development (Ghai, 1966), but under Idi Amin the tax collapsed alongside state services, with grassroots organizations stepping in to fund schools and basic infrastructure (Nabuguzi, 1995).

During the first years of the NRM’s rule, local governments relied heavily on GPT to finance operations. Yet by 2003, GPT accounted for only 40–50% of locally collected revenues, down from 91% in 1961, with wide regional variations (Bahiigwa et al., 2004). In 1999/2000, GPT made up less than 6% of the total local revenue budget (including transfers from the central government), and its yield declined further until abolition in 2005 (Livingstone and Charlton, 2001). Most local government own revenues covered administration, while service provision increasingly depended on central government and donors. Decentralization reforms of the 1990s intensified the mismatch between assigned functions and revenue capacity. While administrative expenses are necessary to operate a local government authority, they implied that – in the popular perception – GPT payment was not directly linked to development activities. This fits well with the facts. Poll tax revenues were too small to cover the investment and recurrent costs of the sub-national expansion of service provision that took place in the 1990s. These expenditures were funded by central government and foreign aid donors.

4.3 After the abolition of the GPT

Local governments were never been fully compensated for loss of GPT revenues (Bakibinga et al., 2018; Eficon Consulting, 2020; Tidemand et al., 2022). The 2008 Local Government Act amendment introduced a Local Service Tax on salaried and self-employed individuals, alongside efforts to strengthen property taxation, business licenses, and market fees. Yet, none of these fully substituted for GPT revenues, and central transfers – largely earmarked and declining in real terms – did not fill the gap (Tidemand et al., 2022). As a result, local governments remain under pressure to expand own-source revenues if they wish to exercise genuine fiscal autonomy. Thus, they have over time introduced a proliferation of taxes, licences, fees and charges, sometimes exceeding 40 categories in a single council (Kjær et al, 2024). Citizens often struggle to distinguish between them, blurring the line between taxes and regulatory fees. Paradoxically, the abolishment of a major source of income (the GPT) combined with the introduction of other but insufficient taxes, has created a situation where the number of local taxes and fees has increased but the incomes from these have not.

4.4 Summary

The post-colonial trajectory of local taxation in Uganda reflects both the endurance of colonial legacies and the disruptions brought about by political change. The graduated poll tax, inherited from the colonial period, remained central to subnational finance for decades, but its coercive enforcement and regional disparities generated growing resistance, eventually turning it into a political liability. Although decentralization reforms of the 1990s and 2000s were intended to strengthen local autonomy, the abolition of the graduated poll tax in 2005 instead fragmented local revenue systems and left local governments increasingly dependent on central government transfers and external aid. These developments highlight how Uganda’s fiscal history has been shaped simultaneously by long-term continuities in institutional practices and sharp breaks driven by political pressures. The following section examines these continuities and discontinuities more closely, showing how political change and institutional legacies together account for the persistent tensions in Uganda’s tax system.

5. Continuities and discontinuities in Uganda’s taxation history

Uganda’s fiscal history reflects a combination of long-term institutional continuities and sharp ruptures, each shaped by political change, popular resistance, and shifting administrative capacities. While certain patterns of centralized authority, reliance on local intermediaries, and popular tax resistance have endured across centuries, moments of political upheaval – colonial conquest, independence, the NRM’s decentralization reforms of the 1990s, and the 2005 abolition of the Graduated Personal Tax (GPT) – have produced structural breaks that reshaped the relationship between taxation, governance, and legitimacy. The use of taxation to reinforce political legitimacy also exhibits remarkable durability: in different periods, taxes symbolized submission to the king, compliance with colonial rule, or loyalty to post-independence regimes.

Another enduring feature is the reliance on local intermediaries to mediate between the state and taxpayers. Chiefs were indispensable in both pre-colonial and colonial regimes, while local council officials and contracted collectors have played a similar role since independence. This reliance on localized enforcement has entrenched a pattern of mediated state–citizen relations in which taxation is experienced not primarily as a national obligation but as a negotiation with local authorities. At the same time, regional disparities in tax compliance have persisted across centuries. Centralized regions such as Buganda historically recorded higher rates of compliance, while northern and eastern Uganda have long been characterized by weaker enforcement and lower payment rates. These variations not only reflect differences in historical state capacity but also continue to shape perceptions of equity and legitimacy in the tax system.

Tax resistance has also been a recurrent force in Uganda’s fiscal trajectory. From the Nyangire Rebellion of 1907 in Bunyoro to widespread anti-GPT protests in the 1990s, taxation has repeatedly served as a focal point for political contestation. Evasion, avoidance, and outright rebellion have shaped the design and survival of tax instruments, underscoring the role of popular agency in fiscal history. Such resistance has not merely been reactive but has actively contributed to structural changes, including the abolition of GPT in 2005. In this sense, popular opposition to taxation has been both a constraint on state capacity and a driver of fiscal innovation.

Discontinuities, however, are equally striking. The decentralization reforms of the 1990s formally transferred service delivery responsibilities and taxing powers to local governments. Yet, without adequate revenue bases this reform generated a paradox of administrative expansion coupled with fiscal dependency. The abolition of GPT in 2005 marked the most significant rupture in Uganda’s taxation history since independence, eliminating the single most important source of local revenue. In its place, local governments turned to a proliferation of minor taxes, licenses, and fees. This fragmentation undermined administrative efficiency, reduced predictability, and weakened the fiscal link between citizens and local authorities. The decline of the GPT also transformed the role of local tax collectors, who once embodied the authority of the state in rural communities but have since lost much of their fiscal and political significance.

The combined effect of these reforms has been to entrench local governments’ reliance on central transfers, often earmarked and restrictive in use. Far from empowering local governments, the reforms of the National Resistance Movement era deepened vertical dependency and weakened local accountability. What emerged was not a strengthening of the local social contract but a further centralization of fiscal power. In this respect, Uganda’s fiscal history illustrates the persistence of institutional legacies alongside structural breaks, showing how taxation has remained a central instrument of political authority while repeatedly failing to establish a sustainable foundation for autonomous local governance.

6. Conclusion

The history of taxation in Uganda demonstrates the enduring tension between institutional continuity and structural rupture. From the tribute systems of pre-colonial kingdoms through the colonial Hut, Poll, and Graduated Personal Taxes, and into the fragmented revenue systems of the post-independence period, fiscal practices have consistently reflected both the persistence of older patterns and the disruptive effects of political change. Centralized control over major taxes, reliance on local intermediaries, and recurring resistance to taxation have endured as defining features of Uganda’s fiscal trajectory. These continuities highlight the deep historical roots of state-citizen relations in taxation, where revenue collection has always been closely tied to questions of legitimacy and authority.

At the same time, Uganda’s taxation history is punctuated by significant ruptures that have reshaped the fiscal landscape. The colonial imposition of cash taxes, the decentralization reforms of the 1990s, and especially the 2005 abolition of the Graduated Personal Tax fundamentally altered the basis of local government finance. These breaks disrupted established systems of collection and accountability, leaving local governments increasingly dependent on central transfers and eroding the fiscal link between citizens and their representatives. The result has been a paradox of expanding administrative responsibility without commensurate fiscal capacity.

Together, these continuities and ruptures underscore the resilience of institutional legacies and the limits of reform when implemented without adequate attention to history. Uganda’s contemporary struggles with fragmented revenue systems, low compliance, and heavy dependence on the central state cannot be understood without reference to the longue durée of its fiscal development. Taxation has been more than a technical matter of raising revenue; it has been central to state formation, local autonomy, and political legitimacy.

Looking ahead, any effort to strengthen Uganda’s tax system must grapple with this dual inheritance. Reform strategies that ignore historical continuities risk repeating past failures, while those that neglect the disruptive effects of abrupt policy changes risk undermining already fragile state–citizen relations. A more effective and equitable fiscal system will require not only technical adjustments but also a recognition of taxation’s political and historical role in shaping governance. Only by reconciling the weight of institutional legacies with the need for innovation can Uganda build a tax system that supports both national development and sustainable local autonomy.

References

Ali, M., and Fjeldstad, O.-H. (2023). Pre-colonial centralization and tax compliance norms in contemporary Uganda. Journal of Institutional Economics. Vol. 19(3): 379-400.

Ali, M., O.-H. Fjeldstad, and A.B. Shifa (2020). European colonization and the corruption of local elites: The case of chiefs in Africa. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 179: 80-100.

Apter, D. E. (1961). The political kingdom in Uganda: A study in bureaucratic nationalism. Princeton University Press.

Asiimwe B. G. (2022). (Mis)management of sub-nationalism and diversity in “nations”: The case of Buganda in Uganda, 1897 – 1980. Kampala: Makerere University Press.

Bahiigwa, G., Ellis, F., Fjeldstad, O.-H. and Iversen, V. (2004). Uganda rural taxation study. Commissioned report for DFID Uganda (January). Kampala: Economic Policy Research Centre.

Bakibinga, D., Kangave, J. and Ngabirano, D. (2018). What explains the recent calls for reinstatement of a tax considered unpopular? An analysis of graduated tax in Uganda. ICTD Working Paper 79. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies.

Bandyopadhyay, S. and Green, E. (2016). Precolonial political centralization and contemporary development in Uganda. Economic Development and Cultural Change, Vol. 64 (3): 471-508. DOI: 10.1086/685410

Beattie, J. (1960). Bunyoro: An African Kingdom. Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Burke, F. G. (1964). Local government and politics in Uganda. Syracuse University Press.

Constitutional Review Commission (2003). Report of the Commission of Inquiry (Constitutional Review) Findings and Recommendations. Kampala, Uganda, Makerere University Printery (10 December).

Crook, R. (2003). Decentralisation and poverty reduction in Africa: the politics of local-central relations. Public Administration and Development, Vol. 23(1): 77–88.

Davey, K. (1974). Taxing a peasant society. The example of graduated tax in East Africa. London: Charles Knight and Co.

Doornbos, M. (1975). The Ankole Kingship Controversy. Kampala: Fountain Publishers (new edition 2001).

Eficon Consulting (2020). Local government own source revenue mobilisation strategy. Consultancy report reviewing the legal, policy and administrative framework for local government revenue management and design of a local government own source revenue mobilization strategy in Uganda.

Englebrecht, P. (2002). Born-again Buganda or the limits of traditional resurgence in Africa. The Journal of Modern African Studies, Vol. 40(3): 345-368.

Farelius, B. (2012). Origins of kingship traditions and symbolism in the Great Lakes Region of Africa. Kampala: Fountain Publishers.

Fjeldstad, O.-H. and Therkildsen, O. (2008). Mass taxation and state-society relations in East Africa. In: D. Braütigam, O.-H. Fjeldstad and M. Moore (Eds.). Taxation and state building in developing countries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, Chapter 5: 114-134.

Furley, O.W. (1959). The Sudanese troops in Uganda. African Affairs, Vol. 58(233): 311-328

Gennaioli, N. and Rainer, I. (2007). The modern impact of precolonial centralization in Africa. Journal of Economic Growth, Vol. 12(3): 185-234. DOI 10.1007/s10887-007-9017-z

Ghai, D.P. (1966). Taxation for development: a case study of Uganda. Nairobi: East African Publishing House.

Good, C. (1972). Salt, trade, and disease: Aspects of development in Africa’s Northern Great Lakes Region. The International Journal of African Historical Studies, Vol. 4: 543-586.

Government of Uganda [GoU]. 1994. Iganga tax riots commission of inquiry report. (July). Kampala: Ministry of Local Government.

Government of Uganda [GoU]. 1987. Report of the commission of inquiry into the local government system. Kampala.

Hicks, U. (1961). Development from below. Local government and finance in developing countries of the Commonwealth. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Ingram, K. (1994). Obote: a political biography. London: Routledge.

Jamal, V. (1978). Taxation and inequality in Uganda, 1900-1964. The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 38(2): 418-438.

Johannessen, C. (2006). Kingship in Uganda: the role of the Buganda kingdom in Ugandan politics. CMI Working Paper 8. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute.

Karugire, S.R. (1996). Roots of instability in Uganda. Fountain Publishers: Kampala.

Karugire, S. R. (1980). A political history of Uganda. Nairobi: Heinemann.

Karugire, S.R. (1971. History of the Kingdom of Nkore in Western Uganda to 1896. Oxford: Oxford University Press..

Kasfir, N. (2019). The restoration of the Buganda Kingdom Government 1986–2014: culture, contingencies, constraints. Journal of Modern African Studies, Vol. 57(4): 519-540.

Kiwanuka, M.S.M. (1971). A history of Buganda: From the foundation of the Kingdom to 1900. London: Longman Group Limited.

Kjær, A.M. (2009). Sources of local government extractive capacity: The role of trust and pre‐colonial legacy in the case of Uganda. Public Administration and Development, Vol. 29(3): 228-238.

Kjær, M. (2004). The political influence on local government revenue: why the varying impact? Paper presented for the 2004 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, Chicago. Aarhus: Department of Political Science, University of Aarhus.

Kjær, A.M., Asiimwe, G., and Ali, M. (2024). More taxes paying for less: Citizens’ perceptions of local government taxes in Uganda. Paper presented at the NOPSA conference, Bergen, June 21-25.

Livingstone, I. and Charlton, R. (2001). Financing decentralized development in a low-income country: raising revenue for local government in Uganda. Development and Change, Vol. 32(1): 77-100.

Livingstone, I. and Charlton, R. (1998). Raising local authority district revenues through direct taxation in a low income developing country: evaluating Uganda’s GPT. Public Administration and Development, Vol. 18(5): 499-517.

Local Government Finance Commission [LGFC]. 2002. Fiscal decentralisation in Uganda. Strategy paper. Kampala: Local Government Finance Commission.

Low, D.A. (2009). Defeat: Kabalega’s resistance, Mwanga’s revolt and the Sudanese mutiny. In D.A. Low: Fabrication of empire: The British and the Uganda Kingdoms, 1890-1902. Cambridge University Press, pp. 184-214. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511576522.008

Low, D. A. (1971). Buganda in modern history. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Low, D. A. (1965). Uganda: The establishment of the protectorate, 1894–1919. In V. Harlow and E.M. Chilver (Eds., Vol. 2). History of East Africa. Oxford University Press.

Mamdani, M. (1996). Citizen and subject: Contemporary Africa and the legacy of late colonialism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Mamdani, M. (1991). A response to critics. Development and Change, Vol. 22(3): 351-366.

Muhangi, B.W. (2015). Bureaucracy in Uganda since colonial period to present. International Journal of Sciences: Basic and Applied Research (IJSBAR), Vol. 24(7): 103-116.

Murdock, G.P. (1967). Ethnographic Atlas: A summary. Ethnology, Vol. 6(2): 109-236.

Nabuguzi, E. (1995). Popular initiatives in service provision in Uganda. In: J. Semboja and O. Therkildsen (Eds.). Service provision under stress in East Africa: the state, NGOs and people’s organizations in Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda. London: James Currey.

Nayenga, P. (1981). Review: the history of Busoga. The International Journal of African Historical Studies, Vol. 14(3): 482–499.

Nyakatura, J. W. (1973). Anatomy of an African Kingdom: A history of Bunyoro-Kitara. New York: NOK.

Otunnu, O. (2016). Crisis of legitimacy and political violence in Uganda, 1890 to 1979. African Histories and Modernities. Palgrave McMillan. DOI 10.1007/978-3-319-33156-0

Overseas Development Administration [ODA]. (1996). Uganda: enhancing district revenue generation and administration (unpublished). London: Overseas Development Administration.

Pratt, R. C. (1965). Administration and politics in Uganda, 1919–1945. In V. Harlow and E. M. Chilver (Eds., Vol. 2). History of East Africa. Oxford University Press.

Ray, B.C. (1991). Myth, ritual, and kingship in Buganda. New York: Oxford University Press.

Reid, R.J. (2017). A history of modern Uganda. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Reid, R. J. (2002). Political power in pre-colonial Buganda: Economy, society and warfare in the nineteenth century. Ohio University Press.

Richards, A. I. (Ed.) (1960). East African Chiefs: A study of political development in some Uganda and Tanganyika Tribes. New York: Frederick A. Praeger.

Roscoe, J. (1923). Uganda and some of its problems: Part II. Journal of the Royal African Society, Vol. 22(87): 218-225.

Roscoe, J. (1911). The Baganda. An account of their native customs and beliefs. Cambridge Library Collection – Anthropology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Reprinted 2011: https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139051071

Ssekanwa, J.G. (1970). The development of the Buganda Treasury and its relationship with the British Protectorate Government 1900 – 1955. Thesis Submitted for the M.A. Degree in History, University of East Africa, Department of History, Makerere University College. Kampala.

Taylor, L.E.S. (2023). Strategic taxation: Fiscal capacity and accountability in African states. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Thompson, G. (2003). Governing Uganda: British colonial rule and its legacy. Kampala: Fountain Publishers.

Tidemand, P., Wabwire, M., Kuteesa, F. and Ssegawa, B.J. (2022). Local government field work report, November 2022. Uganda Public Expenditure Review. 2022-23. Dege Consult.

Tilly, C. (1990). Coercion, capital, and European states, AD 990–1990, Oxford: Blackwell.

Tuck, M. W. (2006). The rupee disease: Taxation, authority, and social conditions in early colonial Uganda. The International Journal of African Historical Studies, Vol. 39(2): 221-245.

Uganda Participatory Poverty Assessment [UPPA]. (2002). Deepening the understanding of poverty. Kampala. Ministry of Finance.

Uganda Participatory Poverty Assessment [UPPA]. (2000). Learning from the poor. Kampala. Ministry of Finance.

Uzoigwe, G.N. (1973). Succession and civil war in Bunyoro – Kitara. The International Journal of African Historical Studies, Vol. 6(1): 49–71. doi:10.2307/216973. JSTOR 216973.

West, S. (2012). Policing, colonial life and decolonisation in Uganda, 1957-1960. Ferguson Centre for African and Asian Studies Working Paper No. 03 (February).

Annex 1: Main features of the tax system in Uganda over time

This annex provides a historical overview of taxation in Uganda, tracing its evolution from pre-colonial practices through the colonial era to the post-independence period. It highlights the main types of taxes, their purposes, methods of collection, the actors involved, and the challenges of compliance in each period. The summary underscores how taxation not only generated revenue but also shaped governance structures, social relations, and regional disparities. By examining continuities and changes across these three broad phases – pre-colonial, colonial, and post-colonial – the annex illustrates the enduring legacies that continue to influence Uganda’s fiscal systems and local governance today.

Pre-colonial taxation: centralized and decentralized political entities

In the pre-colonial era, taxation practices reflected the diversity of Uganda’s political landscape, with highly organized systems in centralized kingdoms and more informal arrangements in decentralized societies.

Tax types

Centralized kingdoms such as Buganda, Bunyoro, Toro, Nkore, and Mpororo levied a mix of in-kind and labor taxes: compulsory household levies (bark-cloth, cowrie shells), duties on agricultural and manufactured goods, customs charges on border trade, tribute from conquered territories, and fees in lieu of military service. In-kind labor obligations (“luwalo”) were also common. In decentralized societies of the east and north, taxation was largely informal, consisting of occasional contributions in goods or labor for communal needs.

Purpose of taxation

In centralized states, taxation financed armies, supported royal courts, maintained infrastructure, and reinforced political authority. It also served as a means of integrating conquered territories. In decentralized societies, contributions primarily addressed immediate local needs such as communal projects or ceremonies.

Methods of collection

In centralized kingdoms, village chiefs conducted household censuses and collected levies at regular intervals – often twice a year in Buganda. Payments were made in goods, livestock, or labor. In decentralized societies, contributions were organized informally, typically by village elders when needed.

Actors involved

Kings appointed provincial and village chiefs to collect taxes and mobilize labor. Chiefs reported to higher authorities and could be fined for failing their duties. In decentralized societies, village heads or councils of elders oversaw contributions.

Compliance issues

In centralized states, compliance was enforced through hierarchical authority, fines, and threats of force. Tribute from subjugated territories sometimes required military action to secure. In decentralized societies, contributions were voluntary or based on social pressure, limiting revenue potential.

Legacy and impact on the present

Centralized polities developed strong administrative traditions of systematic tax collection, reinforcing the role of local intermediaries – a pattern that persisted into colonial and post-independence governance. In decentralized areas, the absence of formal tax systems contributed to weaker administrative structures and lower compliance in later periods.

The colonial period: taxation and British rule

The advent of British colonial rule introduced new forms of taxation, designed both to fund the protectorate administration and to integrate Ugandans into the cash economy. These policies reshaped local governance by building on pre-existing institutions in centralized areas and creating new mechanisms in decentralized ones.

Tax types

The British introduced the Hut Tax (1900), Gun Tax (1900), Poll Tax (1905), and later the Graduated Personal Tax (GPT, 1954–1960). Local governments retained minor levies such as market dues, court fees, and fines.

Purpose of taxation

Colonial taxes funded the protectorate administration, infrastructure, and, at times, British war efforts. They also aimed to integrate Ugandans into the cash economy, encourage cash crop production, and reduce reliance on customs duties.

Methods of collection

Taxes were assessed and collected annually, often through direct visits by chiefs or appointed collectors. Enforcement relied heavily on coercion – property confiscation, physical punishment, and public shaming. In Buganda, a portion of Hut and Gun Tax revenue was refunded to pay local officials.

Actors involved

In centralized areas, the British retained hereditary chiefs under indirect rule, granting them authority to collect taxes. In non-centralized areas, local headmen or clan leaders were appointed and reported directly to colonial administrators. Chiefs often retained a share of revenues as remuneration.

Compliance issues

Avoidance was common: households consolidated to reduce liabilities, or people moved to less strictly enforced areas. Coercive enforcement generated resentment, fueling uprisings such as the Nyangire Rebellion (1907), Buganda riots (1945, 1949), and Bukedi riots (1960). Regional compliance varied – higher in the west and central regions, lower in the north and east.

Legacy and impact on the present

The colonial reliance on local intermediaries and coercive collection entrenched a centralized fiscal authority and regionally uneven compliance patterns. The GPT, although unpopular, became a critical revenue source for local governments, leaving a dependency that persisted after independence.

Post-colonial period: persistence and change in local taxation

Following independence, Uganda’s tax system combined inherited colonial structures with new policies, reflecting both efforts to strengthen local governance and the challenges of building fiscal legitimacy. While reforms were introduced, many colonial legacies persisted in practice.

Tax types

At independence, GPT remained the primary local revenue source, supplemented by property taxes, market fees, trade licenses, and later, the Local Service Tax (2008) and other small levies. After GPT’s abolition in 2005, councils introduced numerous minor taxes, licenses, and fees – sometimes over forty per district.

Purpose of taxation

GPT was intended to fund local government operations and, in theory, development projects. After decentralization in the 1990s, local taxes were meant to finance expanded service delivery, though in practice they often covered administrative costs. The post-GPT proliferation of small levies was primarily revenue-driven rather than service-linked.

Methods of collection

Local councils set rates and assigned collectors, often working at village level. Enforcement methods ranged from reminders to property seizure, and sometimes involved informal arrangements. In the post-GPT era, collection became fragmented, with different units responsible for specific fees or licenses.

Actors involved

District and sub-county officials oversaw tax policy and collection, with revenue officers, parish chiefs, and contracted agents collecting payments. In some cases, traditional leaders remained symbolic advocates but not formal collectors.

Compliance issues

Historical distrust of local taxes, unfair assessments, and coercive enforcement reduced compliance. Riots in Iganga (1994) and long-standing regional disparities in payment rates reflected deep-seated resistance. After GPT’s abolition, confusion over the multitude of small levies further discouraged voluntary compliance.

Legacy and impact on the present

Post-independence taxation retained the colonial-era dependence on a single dominant local tax (GPT) until its removal, after which fiscal fragmentation intensified. Central transfers remain the main revenue source for most local governments, limiting fiscal autonomy and reinforcing historical patterns of uneven compliance and weak local tax bases.