Addressing the “seven deadly thins” — weak spots where corruption can fester

Written by

Phil Mason OBE — senior anti-corruption adviser in DFID from 2000 until March 2019. He formally retired from the UK public service after 35 years, 31 of which were with ODA/DFID. He continues in the anti-corruption field in an independent capacity.

Read Phil Mason’s other post in this series:

1. Corruption’s development implications — from wallpaper to worry

Clare Short’s mandate to DFID from 1997 was truly radical. As practitioners, we (or rather I for most of the first few years before a team grew around me) were given licence to challenge orthodoxies, press for change in other departments as well as our own, and encouraged to think transformationally about our ambition at the global level.

The prevailing donor mind-set

To gain a sense of how far the new DFID-approach departed from the norms of the time, we need to understand the prevailing donor mind-set that then ruled (to the extent that anyone actually thought about corruption). Donors looked on corruption almost always as a problem ‘over there’ and ‘with them.’ Where anti-corruption policies were developed, these focused on assisting with institutional reform in developing country systems and protecting aid funds from being lost there through corruption. They also promoted emerging international norms. Examples include UNCAC and corporate social responsibility processes, which highlighted to commercial businesses their responsibilities when operating in these countries. Almost none considered the role of their own country systems in the problem.

So, donors embarked on their anti-corruption journeys seeing the problem through their traditional developmental lens and tended to treat corruption as just another of the development challenges. Not surprisingly, the resulting responses tended towards training, ‘capacity building,’ passing on knowledge about ‘how to defeat corruption,’ and institutional strengthening in the countries themselves. That is what donors do for everything else — that is how they approached corruption. This turned out to be a fateful direction to take (which I will address in a different part of this series, coming soon), but the crucial point for our story was the unspoken consensus that all the action was regarded as having to take place in the ‘victim’ country.

A typical anecdote is the one where a particular donor put huge efforts into reforming the police in one Asian developing country. It was said that they were now capable of actually investigating corruption cases and bringing them to court. But no one had reformed the judiciary. So all the police reform was for nought. The word on the street was that ‘you can’t bribe the police anymore — you just need to buy the judge.’

Donors also failed miserably to co-ordinate amongst themselves. They often sent mixed messages to the host country about whether they cared about corruption or not. They behaved disjointedly when corruption episodes erupted, and cherry-picked what were felt to be easier targets to devote programming to. At the same time, they ignored the complex nature of the problem — challenges demanding a far more coherent approach across multiple sectors all at once.

Thinking in multiple domains

In the UK, the departure point under Clare Short was very different, as recounted in the first of a series of U4 Practitioner Experience Notes on Twenty years of anti-corruption: ministers gave staff in DFID the political authority, in regard to global corruption, to start to address the UK’s problems.

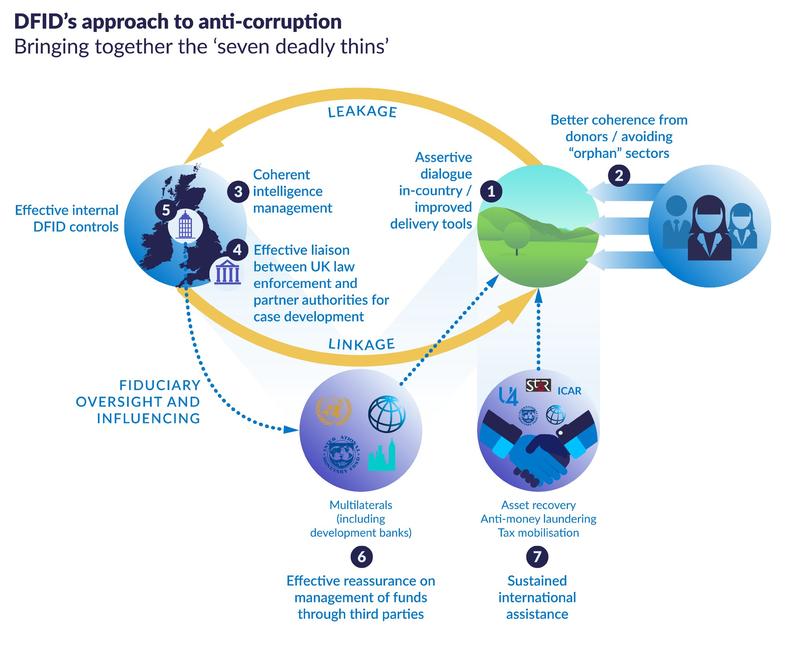

At DFID we conceptualised the key dimensions of the problem we faced — what we saw as the ‘seven deadly thins.’ These were domains where the way we operated created weak points that allowed corruption to fester. Addressing each of the concerns needed to be a part of our response, and was a fundamental shift in how we worked. The illustration below shows where the ‘deadly thins’ were present and addressed.

The seven deadly thins required us to think in multiple domains — in our partner countries for sure, but more broadly, too: at home, and at the inter-state level. This was because corruption even then was showing itself to be an inherently cross-jurisdictional problem.

None of these weak spots have been completely repaired even after 20 years (reasons for which I’ll explore in the PEN series), but despite the daunting challenge each presented, it is inconceivable that there could be any genuine progress without trying to address each of them and to appreciate their inter-connectedness.

Staying just at the partner country level (thins 1 and 2 in the diagram) could never begin to make inroads into the problem. But at the time this is where many donor countries’ efforts began and ended — and, sadly, where it still remains for far too many today.

You can read about how DFID worked to secure a gold-standard UK Bribery act and spend aid money at home to stem illicit financial flows in: Fighting the ‘seven deadly thins’ — starting the DFID journey. This is part of the series Twenty years of anti-corruption — A series on experiences, lessons, and advice for future anti-corruption champions.

About U4

The U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre at CMI works to identify and communicate informed approaches to partners for reducing the harmful impact of corruption on sustainable and inclusive development.

Follow U4

Disclaimer

All views expressed in this post are those of the authors, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the U4 partner agencies, or CMI/U4.