No city is the same: Livelihood opportunities among self-settled Syrian refugees in Beirut, Tripoli and Tyre

Benefits of self-settlement in urban areas

Area-based approaches in response to humanitarian crises

Reconnecting with relatives may be a primary driver in selecting settlement cities in Lebanon

Cities vary in their ability to provide employment, affordable housing, and services

Distribution of assistance to Syrians in urban areas is low and variable depending on location

How to cite this publication:

Robert Forster (2021). No city is the same: Livelihood opportunities among self-settled Syrian refugees in Beirut, Tripoli and Tyre. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI Insight 2021:1)

The large influx of Syrians displaced into urban areas in Lebanon strained infrastructure and available services. Based on a survey of 450 displaced Syrians in Beirut, Tripoli, and Tyre, this CMI Insight sheds light on the challenges and opportunities of urban self-settlement and the benefits for instituting area-based solutions.

Introduction

Urban self-settlement of displaced persons is a global phenomenon and an estimated 80 per cent of displaced persons are currently located in cities worldwide. The case of Syrians displaced to Lebanon is no different: the protracted conflict in Syria forced over 865,000 Syrians to seek shelter in Lebanon as of December 2020, a third of whom have settled in urban areas.

Cities offer a greater variety of opportunities, employment, and services boosting self-reliance among the urban displaced. Yet, these factors vary considerably across Lebanon’s cities. Governmental fragmentation rooted in centre-periphery and confessional differences contributed to uneven economic development in the country since the end of the Lebanese civil war in 1990. Differences between areas are further evidenced by the variations in municipal interventions towards the Syrians displaced after 2011 ranging from the municipal distribution of aid to the imposition of curfews.

In light of widespread socio-economic and infrastructural pressures in the surveyed neighbourhoods, this CMI Insight argues for the continuation and development of area-based approaches addressing urban displacement crises.

Box 1: Urban neighbourhoods in focus

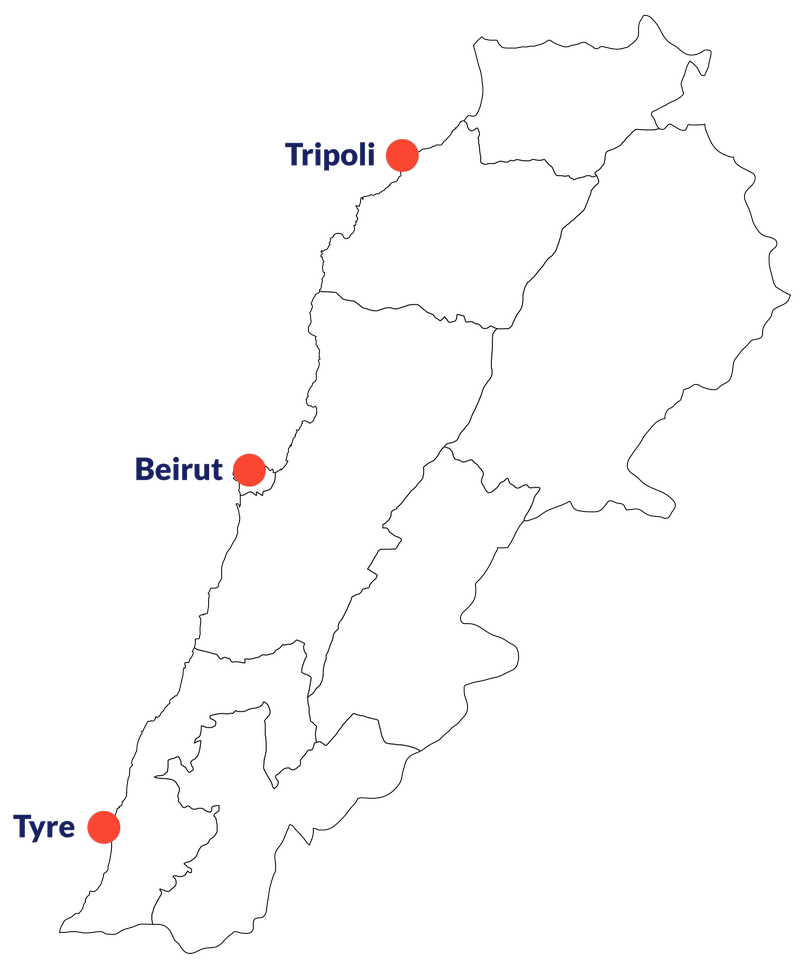

The URBAN3DP survey was undertaken in the following inner-city and informal settlements in Tripoli, Beirut, and Tyre, all with a mix of Syrian, Lebanese, and migrant populations. Beirut and Tyre also included Palestinian ‘gatherings’.*

Beirut: The Beirut metropolitan area is home to 2.2 million including 202,000 registered Syrians. Areas surveyed: Daouk, Sabra (with Gaza Buildings), and Saʿid ʿAwash.

Tripoli: As of 2016, Lebanon’s second largest city had a population of 508,000, including nearly 20% Syrians.** Areas surveyed: Abu Samra (with al-Shawk and a-Shalfi); al-Qubbah, and al-Haddadin.

Tyre: The city has a population of 115,600 with almost 16,000 Syrians. Areas surveyed: Nahr al-Samar, Jal al-Bahr, al-Madiniyyah al-Sanya.

* The survey totaled 450 respondents with 150 respondents in each of the three locations. Surveys took place in Arabic between late February-June 2020. Data was collected using mobile phone software (KoBoToolbox). Many thanks to the surveyors for their dedication.

** Suzanne Maguire et al., “Tripoli City Profile 2016” (Beirut: UN-Habitat, September 2017), 33.

Benefits of self-settlement in urban areas

The no-camp policy towards Syrians in Lebanon forced Syrians to self-settle across the country, many of them in urban areas.[i] Urban areas and cities are attractive options for many displaced persons due to:[ii]

- greater diversity and opportunities for employment, shelter, services, and entrepreneurial prospects in comparison to rural areas.

- greater infrastructure possibilities, including improved services and access to electricity, health care, education, water, waste removal, and transportation.

- better telecommunications services making it easier to communicate with social networks elsewhere.

- increased anonymity for urban refugees and the displaced compared to villages where host populations may be tighter knit and recognise strangers.

- self-settlement, more generally, provides some degree of freedom of movement compared to ‘warehousing’ solutions such as camps.

- pre-existing communities of co-nationals help with integration as well as offering opportunities for expanding social networks and improving livelihoods through securing employment and shelter. Communities of co-nationals also offer safety in numbers.

- the ability to reunite with family, relatives, and established social networks providing not only opportunities of economic improvement, but also companionship and improved mental health.

- access to municipal and governmental services (visas and residency permits), foreign embassies (for consular services), in addition to UN and other humanitarian agencies.

- settling in cities may also provide access to powerbrokers that can intervene on one’s behalf.

Self-settlement in cities is supposed to boost self-reliance by integrating displaced populations into local economies where they can contribute to national growth limiting their reliance on aid. However, legal limitations on, and social discrimination of, refugees and the displaced limit these abilities, exacerbating vulnerability and reliance on aid.

Area-based approaches in response to humanitarian crises

Cities are complex environments for humanitarian intervention. The following issues are often cited as challenges for providing aid to urban displaced persons:

- co-habitation of displaced persons, refugees, migrants, and the urban poor makes targeting difficult.

- aiding the displaced while ignoring other vulnerable groups may lead to tensions.

- a lack of experience and relationships among aid agencies with local municipalities that are themselves often understaffed and underfunded.

- identifying and targeting unregistered displaced persons who are often among the most vulnerable.

- the high number of recipients and their dispersal across urban areas.

- the need for good relationships with local community-based organisations, and for community-based organisations to have relations with target populations.

- that the urban fabric is complex and denser than in villages or rural areas, and therefore requires more knowledge for effective engagement including knowledge of governance and power structures, legal and policy frameworks, and property ownership.

In an attempt to address these issues, area-based approaches (ABAs) aim to provide multi-sectoral support addressing housing, health, water and sanitation, livelihoods, education, and social safety needs to high vulnerability areas.[iii] In the context of addressing urban displacement, ABAs can be beneficial due to:[iv]

- an ‘inclusive’ approach targeting entire populations within areas regardless of nationality and residency status.

- integrating multiple stakeholders on all levels including donors, national and local government, residents, and implementing agencies.

- an opportunity to improve informal areas that often absorb displacement flows in host countries with long-term development benefits.

- a way of bringing together multi-sector/agency interventions and increase coherence and clarity of targets and outcomes.

However, according to expert assessments, ABAs have a variety of challenges including:

- high financial inputs needed to implement programming.

- perpetuating local inequalities between neighbourhoods.

- long implementation periods.

- difficulties in identifying the actors responsible for coordination.

- obstacles in integrating approaches into city- and national-level plans.

- complications in monitoring and evaluation.

These aspects should be considered in light of the following results.

Survey findings

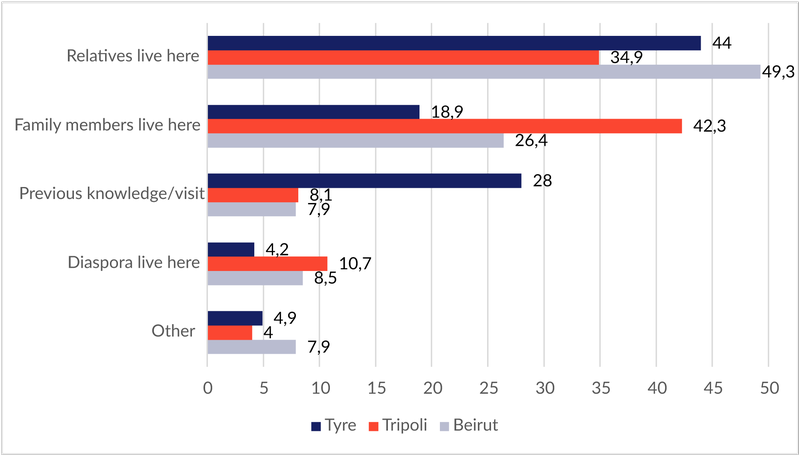

Reconnecting with relatives may be a primary driver in selecting settlement cities in Lebanon

The origin of Syrian displaced persons – whether urban or rural – varied considerably between cities in Lebanon. In the northern city of Tripoli, 85% of Syrians were from urban origins, but this dropped considerably in Beirut and especially Tyre where only one-third of respondents were from towns or cities.

The distribution of displaced persons from urban or rural origins indicates the role of pre-conflict Syrian-Lebanese migration networks and its impact on the self-settlement of Syrians.[v] Self-settlement in Tyre, in particular, appears to be influenced by pre-conflict migratory labour and had the largest portion of households where an individual either possessed previous knowledge of the city or had previously visited (see Figure 1).

Regional clustering in particular cities is a further indicator of linkages between Syrian governorates and Lebanese cities of which Tripoli is a particularly good example. As reported by UN-Habitat, many Syrians from Homs had either spent time with relatives in Tripoli before 2011 (predominantly middle class) or were employed there (predominantly among the working class) – a factor confirmed by survey results.[vi]

Most cases of settlement, however, were reported to be due to the presence of a family member or relative who had settled first as a ‘pioneer’ and was later joined by other family members. According to UN-Habitat, in some Tripolitan neighbourhoods, a fifth of Syrians reported arriving before 2011. In all three Lebanese cities, the presence of family and relatives was ranked highest among the reasons for settling in a specific city.

Cities vary in their ability to provide employment, affordable housing, and services

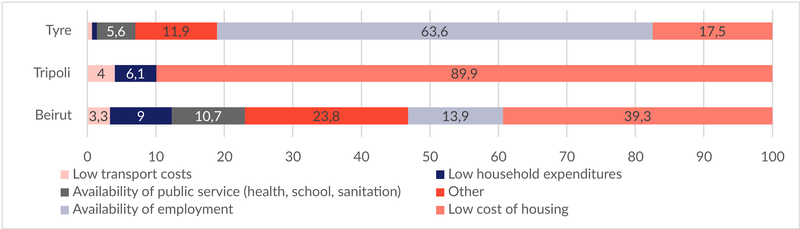

The decision to settle in a particular neighbourhood appears to be the result of three major concerns: access to employment, the cost of housing, and access to services.

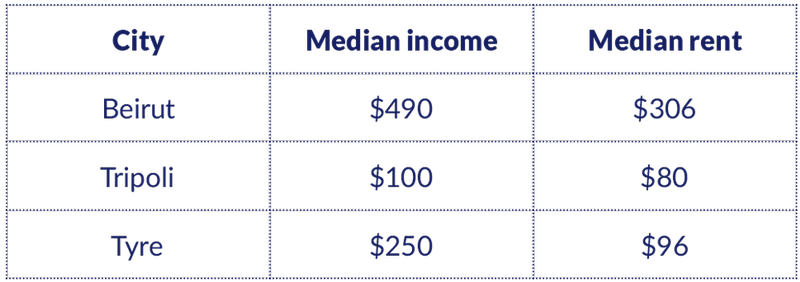

In Tripoli, the primary factor when choosing accommodation for Syrians was the cost of rent (as reported by 90% of respondents), whereas the main challenge was a lack of employment (reported by 62% of respondents) (see Figure 2 and Table 1). 64% of respondents in Tripoli said that no adult men in the household had worked in the last 30 days (93% of women). Moreover, over half of the respondents noted that the condition of their accommodation was “inadequate” and one in ten had issues with the electricity.

Estimates based on self-reported incomes and expenses in unstable financial environment. Hyperinflation during the survey period made USD exchange rates fluctuate daily. The exchange rates are based on estimated unofficial rates for USD 1 reported by surveyers and corroborated through online reports: Feb. 2450 LBP; Mar. 2600 LBP; Apr. 3000 LBP; May 4300 LBP; Jun. 9200 LBP; Jul. 8000 LBP.

Rent is the largest expense for over half of displaced households. According to UN-Habitat, 52.5% of Syrian households use between 40-100% of their income on housing. Moreover, a third of the 450 respondents were dissatisfied with the condition of their accommodation.

Households in Tyre, in contrast to Tripoli, listed the availability of work (64% of respondents) as the main reason for choosing their neighbourhood. There was also a decrease in the level of unemployment: respondents in Tyre reported the highest rate of employment with 73% of respondents stating that at least one adult male had worked in the previous 30 days (76% of women).

Respondents from Beirut, on the other hand, highlighted the need for affordable housing (39%) in addition to the availability of work (14%) as reasons to choose a particular neighbourhood. Beirut had the highest level of full-time employment (which was non-existent among respondents in Tripoli).

One in ten households in Beirut further highlighted the desire to access public services as a reason for settlement. Nonetheless, Beirut households listed a lack of services and other infrastructural issues at a higher rate than other cities including the lack of electricity, issues with the water supply, as well as low quality housing and health facilities. Despite this, respondents in Beirut were the most content with their accommodation: 79% said it was adequate.

Distribution of assistance to Syrians in urban areas is low and variable depending on location

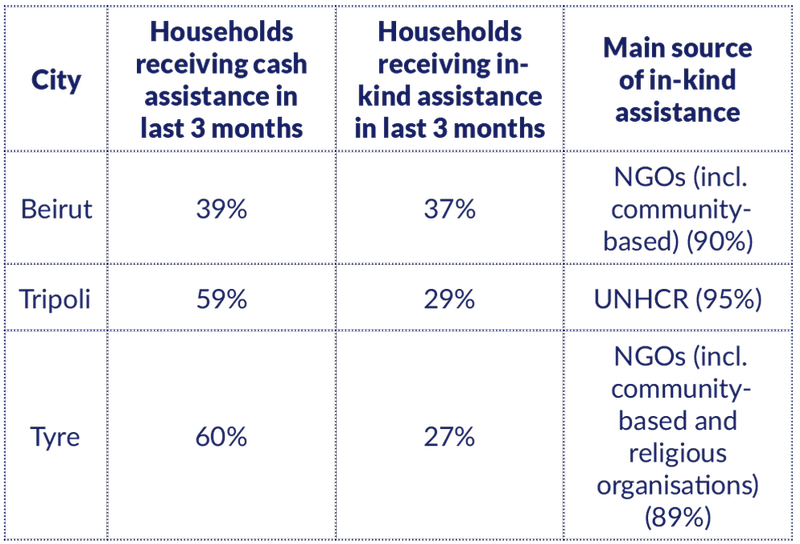

Beirut and Tripoli have high rates of UNHCR registration at 94% and 96% respectively, whereas roughly a fifth of respondents surveyed in Tyre were not registered or recorded with UN Agencies.

There were disparities in the degree of assistance provided to self-settled Syrians in Lebanon’s cities. Beirut has the lowest number reporting the receipt of cash assistance in the 90 days before surveying at two-fifths of households, compared to three-fifths in Tripoli and Tyre. Nearly all respondents in the latter cities received cash assistance from the UN Agencies, compared to Beirut where 40% of respondents reported cash assistance from local organisations.

Material (in-kind) assistance was more equal across cities with slightly higher rates in Beirut than in Tripoli and Tyre (see Table 2). Providers of material assistance in Beirut and Tyre were most likely to be local organisations, whereas in Tripoli it was the UNHCR. Respondents highlight the essential role played by local organisations in providing livelihood assistance. The most common items were food baskets, but also included blankets, fuel, clothes, and heating sources.

Lebanese-Syrian relations vary between Lebanon’s cities where tensions are often related to local demographics, political affiliations, and poverty rates

Despite reports that the Lebanese and Syrians generally do not compete for the same jobs, unemployment increased among the Lebanese population amidst the Syrian influx.[vii] The displacement crisis was blamed for a rise in living costs and rent due to the increased competition in the crowded housing market. The provision of assistance to only displaced populations may engender hostility from host populations who are often also vulnerable and face comparable livelihood issues.

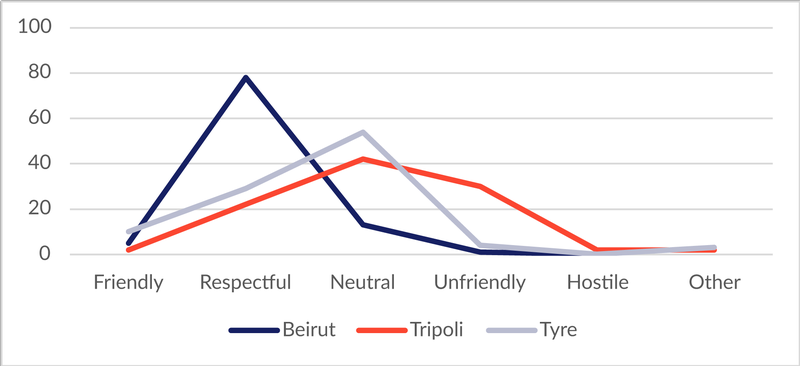

Responses indicated that host-community relations were the friendliest in Beirut, mostly neutral in Tyre and the least friendly in Tripoli. Indeed, 59% of respondents in Tripoli said that the problems were related to “political differences” and communal tensions manifested in a series of violent conflicts between 2011 and 2014.

Conclusion

Regardless of city, survey results highlight vulnerability and precarity of respondents who occupy licit, but often informal spaces in the city. The survey underscores the three key elements that make cities attractive to Syrians in Lebanon: connecting with family and friends, employment prospects, and affordable rentals.

The high degree of variability found in the surveyed areas underlines the need for context-specific approaches to area-based interventions such as those currently being adopted by agencies as the UNHCR. However, UN agencies are not the sole or, in some cases even the primary support for urban self-settled Syrians in these cities, which underscores the need to take an inclusive approach to the unique configuration of service and aid providers in each area.

Endnotes

[i] Lama Mourad, “‘Standoffish’ Policy-Making: Inaction and Change in the Lebanese Response to the Syrian Displacement Crisis,” Middle East Law and Governance 9 (2017): 249–66; Marwa Boustani et al., “Responding to the Syrian Crisis in Lebanon Collaboration between Aid Agencies and Local Governance Structures” (International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), 2016).

[ii] Kofi Kobia and Leilla Cranfield, “Literature Review: Urban Refugees” (Ottawa: Refugees Branch, Citizenship and Immigration Canada, September 2009); Sarah Dryden-Peterson, “‘I Find Myself as Someone Who Is in the Forest’: Urban Refugees as Agents of Social Change in Kampala, Uganda,” Journal of Refugee Studies 19, no. 3 (2006): 381–95; Jeff Crisp, Tim Morris, and Hilde Refstie, “Displacement in Urban Areas: New Challenges, New Partnership,” Disasters 36, no. 1 (2012): 23–42; Lucy Hovil, “Self-Settled Refugees in Uganda: An Alternative Approach to Displacement?,” Journal of Refugee Studies 20, no. 4 (2007): 599–620; Marc Sommers, “Urbanisation and Its Discontents: Urban Refugees in Tanzania,” Forced Migration Review 4 (April 1999): 22–24.

[iii] Elizabeth Parker and Victoria Maynard, “Area-Based Approaches in Urban Settings: Compendium of Case Studies” (Geneva: Urban Settlements Working Group, Global Shelter Cluster, May 2019).

[iv] Summarised from: Parker and Maynard, “Area-Based Approaches in Urban Settings: Compendium of Case Studies,” 6–13 and Victoria Maynard et al., “Thinking Bigger: Area-Based and Urban Planning Approaches to Humanitarian Crises’,” Briefing (London: International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), 2017).

[v] According to Syrian government statistics, there were over a million Syrians in Lebanon in 2010.

[vi] UN-Habitat and UNHCR, “Housing, Land and Property Issues of Syrian Refugees in Lebanon from Homs City” (Beirut: UN-Habitat, November 2018), 18–19.

[vii] Suzanne Maguire et. al., ‘Tripoli City Profile’ (Beirut: UN-Habitat, September 2017), pp. 49-50