Neglect, Control and Co-optation: Major features of Ethiopian Youth Policy Since 1991

2. Government-Youth Interaction in Ethiopia: a Brief Historical Background

3. Youth-focused Policies, Institutions and Programmes

3.2. Massification of Higher Education and Graduate Unemployment

3.3 Micro and Small Enterprises and Vocational Training

3.5. The Formal Youth-focused Institutions

3.5.1. Ministry of Youth, Sports and Culture/ Ministry of Women, Children and Youth

3.5.3. Ethiopian Youth Federation

4. EPRDF’s Ways of Controlling and Mobilizing the Youth

4.1. Adegegna Bozene – Dangerous Vagrants’ Prevention Law

4.2. Targeting the Youth after the Controversial 2005 Elections

4.3. Youth Co-optation through Patronage Politics

4.5. The Presence of Youth in the Ruling Party Leadership

5. Youth-dominated Protests contributing to Major Political Change

5.1. Protests in Amhara and Oromia and the Impact of Social Media

5.2. Youth Protests coupled with EPRDF Division

How to cite this publication:

Asnake Kefale, Mohammed Dejen, Lovise Aalen (2021). Neglect, Control and Co-optation: Major features of Ethiopian Youth Policy Since 1991. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI Working Paper WP 2021:3)

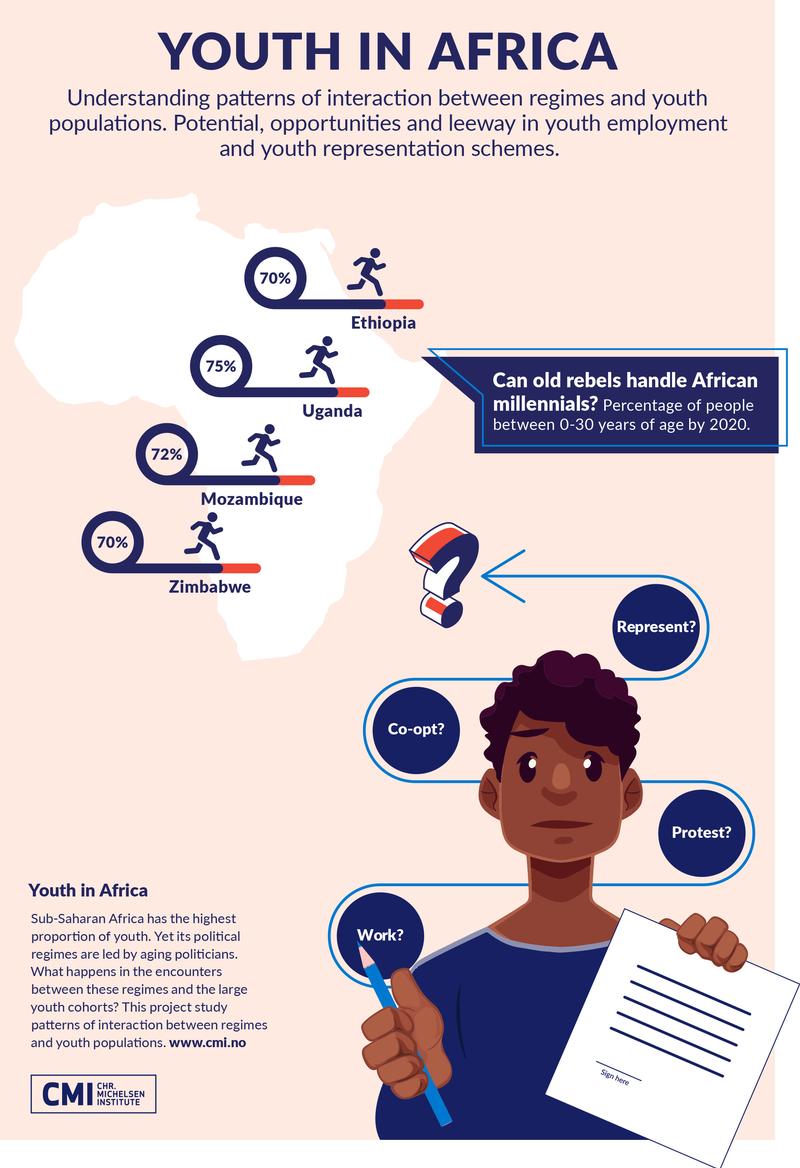

Ethiopia, Africa’s second most populous state, has a young population with more than 70 percent of its inhabitants below the age of 35. Ethiopian regimes have a history of youth neglect and repression, and more recently, co-optation through patronage politics. Unemployment and political marginalization have continued to be a major challenge for young people, also after youth protests contributed to bring Africa’s youngest Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed to power in 2018.

1. Introduction

Ethiopia is one of several countries on the African continent which has been led by governments originating from liberation movements, coming to power at the end of a civil war. Ethiopia is also among the many African countries with a large and growing youth population, where more than 70 percent of its inhabitants are below the age of 35 (Getinet, 2003). While the political leaders have continued to justify their hold on power by the victory in the civil war that ended in 1991, the young have no experience with and few memories of the liberation war three decades back. We have therefore seen a growing schism between the aging liberation leaders and the youth. This schism has a varied set of expressions, ranging from youth protests to disengagement and passivity, and from government neglect to containment and co-optation.

It has, however, gradually become apparent for the Ethiopian government and its leaders that the youth population and their interests have to be handled. This paper addresses both the formal and informal mechanisms set up by the Ethiopian government and the ruling party in the post-1991 period to politically and economically engage the young and create avenues for their participation in the Ethiopian body politic. It analyses the overall youth policies of the government and youth-specific economic and political strategies and the positions of youth in the government and the party. The paper also explores the possible impact of the still unfolding political transition in Ethiopia after 2018 on regime-youth interactions.

This working paper is the second in a series of working papers under the project Youth in Africa, where we look at youth employment and representation in Ethiopia, Mozambique, Uganda and Zimbabwe.[1] The project is motivated by the need to find better ways to economically and politically empower the youth in politically fragile contexts. By exploring regime-youth interactions and major policies addressing the young, we aim at getting better insights into whether such policies actually empower the youth, or whether they bind them in patronage relationships and thereby reinforce marginalization.

2. Government-Youth Interaction in Ethiopia: a Brief Historical Background

The historical interaction between government and youth in the Ethiopian context could be seen in terms of control/repression or co-optation rather than allowing the youth to freely contribute to the country’s economic and social development. Following the opening up of post-secondary education in the 1950s under the reign of Emperor Haile Selassie,[2] the social and political consciousness of the students grew, and the young increasingly looked at themselves as agents of political and social change. The Ethiopian student movement developed ideas on how governments should be formed and people be governed (Balsvik, 2005). This brought them into direct collision with the imperial regime. The regime’s response was one of repression and exploitation of divisions within the students. Hence, their relations became confrontational, and its hostile relationship to the students was one of the factors contributing to the demise of the regime in 1974.

Government-youth interaction during the military socialist regime – popularly called the Derg (1974-1991) was not different from the previous regime policies. Those young students, together with the general populace, who brought the 1974 revolution were subjected to the regime’s repression and even mass executions through the so-called Red Terror. After the Derg consolidated its power, the young were obliged to be members and supporters of the regime either by the use of force or through co-optation in the form of establishing a national youth association affiliated with the former Workers Party of Ethiopia.[3]

Youth-government interaction during the EPRDF[4] in power from 1991 is not substantially different from its predecessors but became more systematic and elaborate than earlier. The regime officially recognized the freedom of association but conspicuously used elaborated mechanisms of patronage politics and restrictive laws to co-opt or control youth associations. The government/party controlled the youth by creating party-affiliated youth leagues and associations and state resources were redistributed for the members of the co-opted associations and leagues. Employment opportunities and job creation schemes designed by the government were linked to party membership and loyalty.

This combination of repression and co-optation, feeding the perception of unfair access to political and economic resources, was a major reason for the widespread youth protests starting from 2015. These protests, together with a split in the EPRDF, led to the fall of the EPRDF in 2018, and the emergence of a transformed ruling party, the Prosperity Party (PP), under the leadership of the new Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed. While brought forward by youth wanting a change, the new administration appears to continue many of the previous practices towards the youth, leaving the empowerment and constructive engagement with the youth as a major challenge in contemporary Ethiopia.

3. Youth-focused Policies, Institutions and Programmes

The EPRDF, the ruling party of Ethiopia from 1991 to 2019, has its roots in the liberation struggle against the Derg. The core of the party was the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) with roots back to the Ethiopian student movement of the 1960s. Despite its youthful point of departure, the TPLF/EPRDF did not have a specific youth focus in the first decade in power. One of the reasons for the lacking youth focus was its focus on ethnic politics and representation. The TPLF made ethno-nationalism its core ideology and advocated for the liberation of the Tigray ethnic group from what it called the oppression of Amhara ruling classes. It launched a protracted struggle (from 1975 to 1991) against the military regime and was able to overthrow it by creating alliances with other ethno-nationalist fighters. During the war, the TPLF/EPRDF was focused on mobilizing the peasantry against the military government. After it assumed state power, its development policy was focused on rural areas. So both its ethnic base/ideology and its rural focus contributed to the neglect of the youth in political and economic terms.

In the second decade of its rule, however, the EPRDF gradually moved its focus away from ‘ethnic liberation’ to that of national economic development and a transformation of the agriculturally led economy. Following this reorientation, combined with youth restiveness as seen in the urban areas (particularly in Addis Ababa) from 2001 (Heinonen, 2013), the EPRDF government began to adopt youth-focused policies starting from the beginning of the 2000s.

The EPRDF Programme (2006: 28) specifically describes the youth as potential agents of development:

Enabling the younger generation acquires innovative ideas; professional competence, good ethical background to engage with vigour in development and the building of a democratic order; encouraging the youth to organize independently paving the way for its engagement in the political, economic and social arena and reap the benefits at all levels.

This positive image of the youth was also stated in the country’s first National Youth Policy in 2004. In what follows, we will briefly review major government policies on the youth, youth-focused government institutions, but also how the government sought to control youth opposition to its rule.

3.1 The National Youth Policy

The National Youth Policy was introduced by the Ministry of Youth, Sports and Culture in 2004. The ministry was responsible for following up, directing and co-ordinating youth affairs at the federal level. In line with the national youth policy, regional states also established youth bureaus to coordinate government efforts regarding youth.

The youth policy stressed the need to take important measures to enable the youth to be competent citizens with a democratic outlook, professional competence, skills and ethics to effectively participate in the democratization process and to help youth benefit from the ongoing socio-economic development in the country. Moreover, the policy acknowledged the active role of young Ethiopians in the struggle against oppressive regimes. It particularly recognized the role of young students in the 1960s in mobilizing their communities to bring about social, economic and political changes in the country.

Having ambitions and strategies by itself, however, is not enough to bring about empowered youth to effectively utilize their creativity and productive potentials. Implementation proved to be a difficult task, as it required resources and political will. The National Youth Policy, which has stayed for more than 15 years, needs revision considering many changes that happened since its adoption. When the policy was introduced in 2004, the youth population of Ethiopia was around 28 percent of the total population of around 73 million. The percentage of youth in 2020 has reached 70 percent and the total population of the country is more than 110 million.

3.2. Massification of Higher Education and Graduate Unemployment

The Ethiopian education system has been entangled with the problems of relevance, quality, accessibility and equity for a long time. The gross participation of education at all levels was very low before the 1991 regime change. There were for instance only two public universities in Ethiopia when the EPRDF took power in 1991 (Semela, 2011: cited in Nigusse and Mulugeta, 2019). During the last two decades, however, higher education and student enrolment have grown remarkably. The number of public universities has reached well over forty, and private colleges and universities have expanded at an even faster pace than the public universities.

The rapid expansion of higher education in Ethiopia, what some used to call the ‘massification’ of the tertiary education system (Kedir, 2009: 30), has created an excess labour force. While the numbers of students and graduates in higher education are not too high when contrasted against the country’s total population and size, the comparison vis-à-vis the country’s labour market shows that the number of graduates is beyond what the labour market can absorb.

Hence, with an increased number of graduates comes a growing graduate unemployment. As the findings of research done by Nigusse and Mulugeta (2019: 38) indicates, “graduate unemployment relative to total unemployment increased substantially from 2014 to 2016”. Moreover, “the growth rate of graduate unemployment is higher than the growth rate of graduate employment” for the same period. The overall findings reveal that the trend of “graduate unemployment is increasing in Ethiopia” (ibid), accompanied by social and political unrest in the country.

3.3 Micro and Small Enterprises and Vocational Training

In the national elections of 2005, the ruling party was for the first time challenged by the opposition, particularly in urban areas and among the youth. Although the elections gave the opposition about one third of the seats in the national parliament, contestation over election results led the major opposition to boycott the further process. After popular protests, use of excessive state violence, and the detention of opposition party leaders, the EPRDF was again in control. But it sensed that it had faced challenges during the 2005 election due to its failure to encompass the needs and demands of the youth in general and the urban youth in particular.

EPRDFs’ main answer to the challenges from urban youth since 2005 were urban development schemes. The national youth policy provides references to the creation and development of Micro and Small Enterprises (MSEs) for the youth to encourage entrepreneurial skills rather than being job seekers for government jobs. The Industry and Urban Development Package was issued by the Ethiopian Ministry of Urban Development, Housing and Construction in 2006 to take measures to reduce urban poverty. Among the measures were the micro and small-scale enterprises with specific government budget allocations. Accordingly, 5.2 billion Ethiopian birr was allotted to support around 1.2 million individuals with credit facilities to create and run their businesses (Di Nunzio, 2015). The government and state machinery and the party system were entitled to implement the programme. Kebele (the lowest administrative level in Ethiopia) and local government offices were responsible for organizing and coordinating the policies and programmes of the schemes. In this context, it was the kebele officials and local government offices who were entitled to select beneficiaries and manage the funds as partners (ibid).

These urban development schemes that were introduced immediately after the 2005 election were clearly intended to achieve political goals. Though the developmental agenda of the state should not be underestimated, the tacit/unstated objective of the government was political – winning back urban support that it had lost to the opposition parties during the 2005 election. The project of small-scale enterprises enabled the regime to reach out to a large number of people and it consequently used the scheme to recruit members for the ruling party. According to Di Nunzio (2015), it was the party-affiliated youth and women’s associations that involved in the screening and selection of beneficiaries. Many of the participants in this scheme were to be selected from the youth forums established by the government and other party-affiliated organizations to ensure that they were actual or potential supporters or members of the EPRDF. Di Nunzio’s (2015: 1180) findings on the implementation of small-scale entrepreneurship programs in Addis Ababa ascertain that “[MSEs] have been extremely successful in enabling the [… EPRDF] – the party which has ruled Ethiopia since 1991 – to expand its structures of political mobilization and control at the bottom of urban society”. As a consequence, those who were politically excluded were also subject to economic exclusion since the recruitment process required political allegiance. So political exclusion ultimately resulted in economic exclusion.

In addition to the political requirements, those who were to get support through employment schemes needed to have certification from Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) centres to confirm their technical and business skills. In the government’s Plan for Accelerated and Sustainable Development to End Poverty (PASDEP) spanning 2005/06 to 2009/10, TVET programmes and MSE institutions were emphasized as key instruments for poverty reduction and job creation among the youth. The number of TVET training centres increased from 17 in 1999 to 199 in 2004 and its enrolment increased from 3,000 to 106, 305 (MOE, 2008; cited in Broussar and Tsegaye, 2012: 32). However, the quantity was not matched with the quality of graduates to solve the unemployment problem, and many of the graduates remained to be job-seekers rather than being job-creators to run their own business. When the Growth and Transformation Plan (GTP) was launched in 2011/12-2015/16, the MSE sector was once again emphasized to achieve its objectives of being potential employment schemes of the unemployed youth and women.

Despite its adverse effects on the political autonomy of the young, the MSE schemes have been evaluated as crucial for job creation and economic growth. In the last two decades, Ethiopia has recorded double digit economic growth that has been well appreciated by the World Bank and other organizations and MSEs have become the second largest employment generating sector in Ethiopia next to agriculture (Hailai et. al, 2019: 50).

3.4. The Youth Revolving Fund

The latest and maybe the largest youth policy measure from the Ethiopian government is the Youth Revolving Fund, specifically targeting unemployed youth both in rural and urban areas. The multi-billion-birr fund launched in 2017 was introduced as an additional resource for the already implemented government scheme of small and micro enterprises (SMEs). The timing of the introduction of this new scheme was significant and indicated that political events and considerations were again crucial for major youth policy reforms. From 2015, mostly urban youth were directly confronting the government in street protests across the country, opposing political and economic marginalized and repression. The proclamation to introduce the fund was approved by a unanimous vote in its first appearance in the national parliament. The emphasis given by the Speaker of the House during the passage of the proclamation showed the urgency of the issue. He said the fund was urgently needed to alleviate the unemployment problem of the youth through the arrangement of loans and lending to youth-owned enterprises.

The proclamation defines the beneficiaries of the financial resources made available by the fund as youth organized under micro and small enterprises who qualify for the criteria set under the proclamation and the directive to be issued afterwards. The age limit is 18 to 34 applying equally for both males and females – a wider age bracket than the one used in the National Youth Policy and the Small and Micro Enterprise (SME) proclamation, which was 15-29. The fund is supposed to be a permanent source of financing youth-centred projects. The source of the fund is the Ethiopian government and the amount is set to be ten billion Ethiopian birr (over 364 million USD). The Ministry of Finance and Economic Cooperation is the responsible federal government organ for the redistribution of the fund to appropriate authorities and ensuring its effective implementation as designed by the proclamation. The Ministry is empowered to transfer the consolidated fund and its proceeds to the Commercial Bank of Ethiopia – a bank that is entrusted to administer the fund on behalf of the federal government.

Based on the proposals initiated by the beneficiaries as mentioned above together with the approval/support of relevant authorities and microfinance institutions, the fund will be used for the supply of capital goods necessary for implementing income-generating projects and cover its operating costs. Moreover, the proceeds of the fund will be transferred to the youth on a loan basis.

The fund is distributed to the nine regional states of Ethiopia as determined by the Ministry based on the size of the youth population of each region. In this regard, the Oromia and Amhara regions are the largest recipients of the fund due to their large number of youth. The micro-financing institutions in each region are responsible to enter into an agreement with the beneficiaries (youth organized in SMEs) as per the proposals of the beneficiaries and the terms and conditions of the Ministry of Finance and Economic Cooperation.

The procedures for obtaining money from the fund require the applicants to first organize themselves in groups consisting of at least five members. Then they have to develop a project proposal screened and reviewed by a committee consisting of experts and officials. If successful, the applicants have to deposit at least 10 percent of the fund they requested. The maximum amount they can receive ranges from 200,000 to 300,000 Ethiopian Birr with a five-year grace period. They are also required to receive training on how to manage a business which should not be less than one month.

Despite its potential contribution to job creation for the unemployed, the implementation and success of the Youth Revolving Fund are still to be seen. By interviewing several individuals both from the would-be beneficiaries and experts, Samson Berhane, the editor-in-chief of the Ethiopian Business Review argues that “the means of allocation used by the government entities expose the fund to misappropriation and corruption [… and] a misguided attempt to trim down the unemployment rate, not backed by innovative solutions and ideas” (Samson, 2018). In interview with youth in Addis Ababa who had submitted a proposal of a project plan to use the advantages of the youth revolving fund, it appeard that they were unable to get a response from the local government office. Young interviewees stated that they instead were considering migrating to Europe in search of a job and a better life as others in similar conditions did. One interviewee, being unable to secure a loan from the government body, said “there were ten people in my group. Seven of them migrated to Libya to try and get to Europe […]. I am looking for some money to do the same. I don’t trust the city administration any more” (Samson, 2018).

As large parts of the funds distributed to the local administrations remain unutilised, there seem to be procedural bottlenecks in the disbursement of the money to beneficiaries. According to Ethiopian Business Review, the administration also blame the unemployed youth for lacking the necessary skills and knowledge to utilize the money, and even some of the applicants thought that the money was to be distributed as a gift without a need to return after securing profits. The then Minister of Youth and Sport, Eristu Yirdaw, was seriously criticized by the parliamentarians when he presented his 8-months report about the performance of the Ministry in disbursing the fund for the youth. They criticized him for introducing procedural bottlenecks for the youth to get the fund, which makes the youth fed up and lose confidence to apply. They also pointed out that the implementation had become susceptible to corruption because the organ that is responsible for managing the fund is also responsible for following up the implementation. This leads to a lack of transparency. It is therefore recommended to establish an independent body to follow up the implementation process.

3.5. The Formal Youth-focused Institutions

Job creation schemes, focussing on the economic empowerment of the youth, have long been favoured by national governments as well as international donors as a way of handling large youth populations. There is however a growing realisation that youth also have to be politically engaged, through formal and informal institutions. In the Ethiopian context, the formal representation of youth was not on the agenda during the first decade of the EPRDF regime, due to its ethnic and rural focus. Gradually, accompanying the economic policies targeting the youth, political youth representation came up on the agenda. The political engagement of the youth has happened after significant political events, many of them challenging the status quo and the popular base of the ruling party - indicating that the reforms aimed at control rather than empowerment of the youth.

3.5.1. Ministry of Youth, Sports and Culture/ Ministry of Women, Children and Youth

It took a decade for EPRDF in power to organise a separate ministry dealing with the youth agenda. The Ministry of Youth, Sports and Culture, formally established in 2001, was mandated to devise youth policies to support and coordinate the activities of the youth in the country. The ministry was however seen as one of the least powerful within the cabinet. The responsibility for youth was transferred to the Ministry of Women, Children and Youth (MWCY) since 2010. As per Proclamation No. 1097/2018, the new ministry was entitled with the powers, among others, to design and implement strategic plans to ensure that opportunities are created for women and youth to actively participate in the political, economic and social affairs of the country.

3.5.2. Youth Forum

The National Youth Policy of Ethiopia (2004) stipulated the formation of a nationwide youth forum through the coordination of the Ministry of Youth, Sports and Culture. There is, however, no standing national youth forum as outlined in the youth policy. Nonetheless, the Addis Ababa city administration established a youth forum following the 2005 elections. (Di Nunzio, 2015). The Forum was organized to bridge the gap between government institutions and the youth that was observed in the 2005 election where the youth opposed the government and overwhelmingly supported the opposition CUD Party. During the protest that followed the controversial election results, the youth protested en masse against the government. This event prompted the government to establish the Youth Forum to create avenues for connecting the youth and government institutions. Gebremariam (2017) describes how the Forum essentially was a tool for Prime Minister and ruling party leader Meles Zenawi to directly communicate with the youth and to enrol more youth leaders in the system of EPRDF loyalists. The fact the forum was closed down around 2007, when the EPRDF had secured its position again after the 2005 electoral challenge, is an indication of the ad-hoc and situation-specific reason for establishing this institution.

3.5.3. Ethiopian Youth Federation

The Ethiopian Youth Federation was founded in 2009 to represent the interests of the youth at the national level. The federation is composed of regional youth federations which in turn comprise various youth associations at regional and local levels. Their stated objectives are to create avenues for youth participation in the country’s development activities and democratization processes at all levels.

The national youth federation itself is the result of the National Youth Policy (2004) that emphasized the active participation of the youth in the political and economic processes of the country. It recognizes the importance of youth “to participate, in an organized manner, in the process of building a democratic system, good governance and development endeavours, and benefit fairly from the outcomes.” The Ethiopian youth federation mobilizes its members to participate in youth volunteering programmes but raises the issue of financial, human and communication constraints to mobilize a large number of youths.

The local and regional youth associations’ historical ties to the ruling party nevertheless reduces the autonomy of the Youth Federation and its ability to serve as a meaningful arena for young people to participate and influence their own affairs. During the liberation struggle, the TPLF established mass organisations among youth, women and peasants all over Tigray, which were used to raise the consciousness of TPLF’s ideology and policy on the grassroots (Young 1997). After the war was won in 1991, these were replicated in all the regions controlled by EPRDF’s member parties, as ethnic based mass-based associations. From the start, the organisations had their representatives in the EPRDF Congress. After 1997, however, it was decided that the Youth Associations, together with the Women’s and Peasant’s Associations, should be formally independent from the party, and should have no role in internal party affairs. The strong linkage between the associations and the party has nevertheless continued (Vaughan and Tronvoll 2003). Although formally non-governmental, they are seen as gate-keepers of access to government resources, for example micro credit. In addition, the Youth Federation is still fully dependent on the Ministry of Youth and Sports for funding of its activities.

4. EPRDF’s Ways of Controlling and Mobilizing the Youth

4.1. Adegegna Bozene – Dangerous Vagrants’ Prevention Law

The major official documents, policies and institutions of the government and the party during the second decade of EPRDF in power presents the youth as vehicles of positive social and economic change. In practice, however, the political leadership and also some policies express an ambiguous, if not negative image of the youth, an indication of an anxiety of youth being trouble-makers and disruptors. Prime Minister Meles Zenawi used for instance the expression adegegna bozene – dangerous vagrants – to describe youth protesters after the contested 2005 elections. This attitude was also reflected in the 2004 Vagrancy Control Proclamation which considers the youth as potential threats to political stability and regime survival.

Proclamation No. 384/2004 entitled “Vagrancy Control Proclamation” came into effect on the 27th of January 2004. As it is clearly stated in the Preamble, the government justified the enactment of the Proclamation due to the increment of what it called vagrancy throughout the country and the threat it created to the tranquillity and order of the people. Hence, it was introduced to dispel the threat of vagrancy and bring criminals to justice for the sake of rehabilitating them and protecting the safety of society. The definition given to vagrancy in the proclamation is very broad and almost includes all jobless individuals in the country and minor offences which were tolerable in the Ethiopian context. From the essence of the proclamation, it can easily be deduced that urban youth – particularly the unemployed were the targets of the law. To put it in another way, the law not only criminalized the unemployed but also securitized them.

The heavy reliance of the government to control the youth by using the 2004 Vagrancy Control Proclamation instead of the positively framed youth policy showed the lack of political will to implement the major promises of the youth policy - indicating that the youth policy was adopted for its symbolism rather than to direct government action towards the youth.

4.2. Targeting the Youth after the Controversial 2005 Elections

The EPRDF-led transitional government in 1991 for the first time in Ethiopia’s history allowed a multi-party system. The first national elections after the adoption of the 1995 Constitution was conducted in 1995 (EPRDF, 2013). Major opposition parties, complaining that there was not an adequate atmosphere for democratic opposition, boycotted federal and regional elections. In the 1995 elections, the EPRDF and its affiliates won 495 and 45 seats respectively out of the 547 seats in the House of People’s Representatives and most of the seats for the Regional Councils. During the second election, conducted in 2000, the EPRDF and its affiliates won 524 of the 547 seats.

In comparison to the earlier two elections, the 2005 elections were relatively competitive. The opposition parties were allowed to campaign more freely. The fragmented opposition parties also established two major opposition coalitions – the Coalition for Unity and Democracy (CUD) and the United Ethiopian Democratic Forces (UEDF). As a result, the opposition parties made significant gains in their representation in parliament. The EPRDF and its allies, however, maintained a two-thirds majority with 411 seats.

The CUD, which accused the EPRDF of rigging the elections, refused to take its seats, and the disagreement over the results of the elections between the ruling party and the opposition parties deteriorated into post-electoral violence. The response of the government to youth protestors and opposition parties was violent. It rounded top leaders of the opposition parties, particularly of the CUD and a large number of the youth. Many of the opposition leaders who were charged with inciting violence and sedition were given longer sentences.

The reaction of the EPRDF to youth protesters in the wake of the elections was equally punitive. It used the vagrancy control law to repress the genuine demands of the youth for jobs and political participation. Ironically, the much-lauded youth policy was side-lined and youth protestors were criminalized and securitized. Tens of thousands (about 40, 000) of youths who were suspected of supporting the opposition parties, particularly the CUD, were rounded up and sent to detention centres outside of Addis Ababa. The majority of the detained youth were unemployed young men. Meles Zenawi, then chairman of EPRDF and prime minister of Ethiopia alleged the CUD leadership was inciting the unemployed youth intending to overthrow the government (Arriola, 2013: 15). In this context, unemployment was associated with anti-government protests.

Following the 2005 electoral debacle, the EPRDF undertook a policy of mass mobilization of the youth, particularly the urban youth, to strengthen its social base and to recruit supporters. Recruitment of new party members through the use of resource distribution and political exclusion of those who refused to join party membership. Membership in the party grew from 760,000 active party members in 2005 to 6 million in 2010 and 7.5 million in 2015 (Arriola and Terrence Lyons, 2016).

4.3. Youth Co-optation through Patronage Politics

The massive recruitment of party members after 2005 was usually based on the provision of incentives in the form of job opportunities, providing fertilizers for rural farmers, arranging higher education opportunities and providing jobs in public services while punishing opposition members by denying all of these opportunities (Arriola and Lyons, 2016: 81). In addition, the government launched mass mobilization targeting unemployed youth in urban areas. The intensification of Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET) and Micro and Small Enterprises (MSEs) programmes, as described above, could be seen in the light of the government’s intention of creating educational and job opportunities for the unemployed urban youth – often combined with punishments of those who support the opposition parties.

This practice reflects that Ethiopia under the EPRDF has been regarded as an authoritarian neo-patrimonial state, where power is maintained through personal networks between the top leaders of the party and the clients rather than through formal government institutions. Linking party membership to access to resources means that many young people have been joining the party not because of political conviction, but in the hope that their job and educational opportunities will increase. However, this strategy may, in the long run, encourage rent-seeking behaviour among its member, a behaviour the EPRDF was claiming struggling against. This means that it is only one’s party unquestionable loyalty – not professionalism or education – that serves to secure a job or access to career development. Land is the most valuable but scarce resource of the state and the people throughout Ethiopia. The EPRDF not only used land to reward its supporters but also denied its opponents access to land.

As a World Bank report (2012) reveals, party-member favouritism is prevalent in Ethiopia and party members have preferred access to government-owned enterprises and civil services. Several research findings and reports indicate that “granting access to development schemes, including small-scale enterprise programmes, has been used both to reward members of the ruling party and to gain new members by making them, directly and indirectly, dependent on the government for their survival and employment” (Di Nunzio, 2015: 1184; citing Chinigo, 2014; Di Nunzio, 2014; Human Rights Watch, 2010a, 2010b; Lefort, 2012). There were also instances where job applicants to government public services attached their EPRDF membership identity card (Solomon, 2018: 103). On the contrary, perceived or real opponents of the regime were denied such opportunities and even expelled from their jobs for reasons related to their membership to opposition parties.

4.4. The EPRDF Youth Wing

Most political parties across the globe have more or less formalized youth sections (wings, leagues or pioneers. Youth wings commonly act as recruiters for the party, but also educate and train young people in key party functions such as campaigning, fund-raising, political communication and party organization (Mycock and Tonge, 2012). The EPRDF departs from this trend by not having had any specific youth section for the first fifteen years in power. It was not before its 6th party congress in 2006 that a resolution was passed for the establishment of youth and women’s party leagues.

Following the resolution of the EPRDF Congress in 2006, the league’s programme and regulation were made and the youth league was officially formed in May 2009. The League was organized under the four coalition organizations of EPRDF (TPLF, ANDM, OPDO and SEPDM) and the two city administrative councils (Addis Ababa and Dire Dawa) with a total membership of 2,049,788 of which 1,629,892 were males and 419,896 females (EPRDF, 2013). Membership to the Youth League is exclusively limited to those individuals between the age of 15 and 29.

The statute of EPRDF (2006) under article 28 defines youth league as “an association of youth aged 15-29 who have accepted and organized to struggle for the implementation of the EPRDF democratic objectives”. It is an association which strongly tied to and works closely with the EPRDF. It has the right to have its manual, mode of operation and freedom in line with the principles of EPRDF; it is entitled to be represented in the EPRDF Congress, Council and Executive Committee; and has the right to comment, criticize and get a response on EPRDF’s mode of operation and activities (article 28 sub-article 2(a-c)). The youth league will serve as a training forum for the youth to succeed the old generation in taking up the EPRDF leadership positions. Moreover, the youth is expected to learn about the principles of revolutionary democracy, its operational procedures (including democratic centralism) and the strategies of the party to implement its programs.

Due to EPRDF’s centralised organisation and its principle of democratic centralism, it has been difficult for the Youth League to act like more than mouthpiece of the mother party. The League’s main role was to communicate the decisions and programmes of the EPRDF to the youth population and recruit the youth through patronage politics. Young people, and the unemployed youth in particular, joined the Youth League for benefiting from patronage politics. It is equally clear that the EPRDF created its youth league mainly in response to the setback of the 2005 election as a strategy of mass mobilization in Addis Ababa and other major cities of the country (Solomon, 2018). The Youth League was linked to local level administrations at woreda and kebele levels extending the reach of EPRDF to the youths at local levels. Using its budgets and organizational structures, the league was given the mandate to recruit new members and indirectly involved in the selection of participants for government employment schemes.

Following the dissolution of the EPRDF and the formation of the Prosperity Party (PP) in December 2019, EPRDF’s Youth League (excepting the TPLF chapter) has been inherited by the PP. It is too early to state in what directions relationships between the youth section and the party are going to develop.

4.5. The Presence of Youth in the Ruling Party Leadership

Liberation movements turning into a dominant ruling parties in a post-conflict context need to consider policies of party rejuvenation to enhance and prolong its chances of survival in power. In the Ethiopian context, the policy of metekakat, (lit. replace in Amharic) implied a systematic attempt of replacing veteran (older) leaders with younger ones in the party organisation. The policy was adopted by the seventh EPRDF congress held in 2008. According to this policy, 65 years will be the maximum age for assuming a top leadership position within the party (EPRDF, 2013). The policy categorized the leadership in the EPRDF into three. The first-generation included those who participated in the armed struggle. Those individuals who did not involve directly in the liberation struggle but were in the same age group as the combatants are regarded as the second generation. Those outside of this age category were considered as the third generation of the leadership. In the 2008 congress, it was decided to replace top leaders from the first generation within five years starting from 2010 (EPRDF, 2013).

According to the EPRDF, the policy of Metekakat was necessary for the following reasons: 1) it helps to produce new and young leaders in large numbers and within a short period of time, this in turn helps young leaders to be acquainted with leadership skills; 2) before those senior leaders leave their positions through retirement, they can share their knowledge and skills to the younger generation so that it will avoid leadership vacuum in the party; 3) party leadership is a collective work rather than individual special achievement, and hence both the old and the new leadership can work together through this metekakat system; 4) as the purpose is to ensure Ethiopia’s renaissance through development and democracy, the work could not be the responsibility of one generation but requires the combined efforts of different generations – at least three or four generational coordination is required. This is in line with EPRDF’s conviction that a minimum of 50 years is required to realize its developmental programmes through the policy of democratic developmental state, indicating that the rejuvenation policy is aimed at securing its stay in power for at least the next five decades.

Based on this resolution, the former EPRDF leader and PM of Ethiopia Meles Zenawi expressed his will to be replaced by another leader starting from 2010. He, however, broke his promise and continued to serve as the leader of EPRDF. He gave a pretext that his party pressured him to continue in his position. The EPRDF’s ideological journal, Addis Raye (New Vision) (2009: 13) stated:

although our party leader (Meles Zenawi) expressed his will to leave office starting from 2010 and it is also in the interest of our party to implement its decisions of replacing senior officials with new ones, the party decided that it is not the interest of the individual but the party will decide who will leave office when. If the party believes that the presence of that individual is very crucial to the party, it could extend his service. Hence, Meles’s application to leave the position of senior leadership in the party is decided to be executed after the maximum 5-year period.

Meles Zenawi was then re-elected as the chairman of EPRDF and Prime Minister of Ethiopia following the 2010 national election and served for two years until his death in 2012. Haile Mariam Desalegn who succeeded Meles Zenawi did not show any sign that the party will be abided by its policy of metekakat. As pointed out by Arriola and Lyons (2016:84) the appointment of ministers following the 2015 elections marked more of a continuity than change. Accordingly, “… 69 percent of the ministers were holdovers from the pre-election cabinet.” A similar trend was also followed in the legislative branch. In the 2015 elections, the EPRDF allowed most of those parliamentarians who served their first five-year term to rerun for their seats. Thus, more than half candidates were re-elected in the 2015 elections (ibid). Although this policy of maintaining seasoned politicians was intended to keep the EPRDF stable and intact, it appeared to have created frustration among the young and low-ranking members and politicians that there will be no hope for them to be promoted to the upper echelon of the party and government leadership.

The policy of metekakat could have been a means of empowering the young generation to senior leadership positions and relegating those first- and second-generation leaders into advisory positions. But the policy remained largely un-implemented. The divisions that prevailed within the EPRDF following the upsurge of youth protests starting from 2015 foreclosed the possibility of a smooth inter-generational leadership transition.

5. Youth-dominated Protests contributing to Major Political Change

The project of entrenching a domineering developmental state under the aegis of an overarching EPRDF had continued with limited resistance until 2015. The ruling party had been able to crack down on scattered protests and manoeuvre electoral politics in its favour since the beginning of the 1990s. The opposition that challenged the political order in the post-2005 electoral crisis was resolved by the use of violence. The youth had since 2005 been largely pacified by a combination of control and co-optation. From 2015, however, status quo was severely challenged by youth-centred protests, ultimately contributing to the first major political change in the country since 1991 – the fall of the TPLF-dominated EPRDF and the emergence of the Prosperity Party, based on new power bases, centred around a relatively young new Prime Minister, Abiy Ahmed.

5.1. Protests in Amhara and Oromia and the Impact of Social Media

Following the 2015 elections, in which the EPRDF won almost 100 percent, youth protests emerged first in the Oromia and later in the Amhara regions. The protest movements used social media, internet networking and mobile messaging as key instruments for organizing and mobilising the youth for anti-government movements in the country. As a result, the government frequently shut down the internet in the country to halt the protests and used the state media as propaganda tools to discredit the protest movements associating them with what they termed ‘anti-peace forces’ and ‘terrorist organizations’. The fact that mainstream media were being controlled by the state pushed many youths to use the social media networks to oppose government policies and actions and coordinate open protests.

Triggered by the government’s plan for an integrated Master Plan to Addis Ababa and the surrounding cities of the Oromia region, resilient youth protest against the government started in November 2015. The initiative for an integrated master plan revealed in 2014 was seen by Oromo protestors as an instrument to grab land from Oromo farmers in the vicinity of Addis Ababa. The movement was mainly led by university and high school students. It was later joined by workers, farmers and other sectors of the society. According to the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data, Ethiopia country report, there were on an average 26 protests per week from November 2015 to February 2016 in Oromia region (ACLED, 2017). Although the government promised to suspend the implementation of the Master Plan, the protests continued, indicating that the youth grievances go beyond the Master Plan. Perceived ethnic inequalities, economic and political marginalization, the widening gap between the poor and the rich, and unemployment, particularly in the urban areas, exacerbated the grievances against the government.

The youth protest in Oromia spread to the Amhara region in 2016. Amhara opposition activists resented the TPLF domination at the federal level and its influence over the regional administrations. The Amhara activists also made consistent claims to territories within the current Tigtay region (Wolkait, Tsegede, Humera and Raya) that were previously included in Amhara dominated provinces like Gondar and Wollo but transferred to Tigray following the 1991 change of government.

In both Oromia and Amhara, semi-organised networks of youth emerged, centred around each ethnic groups’ longstanding demands and against the repression by the ruling party. These are known as the Querro in Oromia and the Fano in Amhara. Similar youth activism gradually evolved also beyond Oromia and Amhara. Since 2015, we have seen the development of the same kind of youth movements in many ethnic groups, raising political demands such as enhanced autonomy for their ethnic communities. These among others include networks in the largest ethnic groups in Southern Ethiopia – the Ejeto in Sidama, the Zarma in Gurage and the Yelega in Wolayta.

5.2. Youth Protests coupled with EPRDF Division

In parallel with the youth protests, a schism within the ruling EPRDF coalition was widening. The unabated TPLF dominance within the coalition since 1991 was increasingly questioned by the other member parties, and EPRDF’s failure to stop the protests was ascribed to the fact that the ruling party itself lacked good governance and that rent-seeking was rampant within the party organisation. The party started therefore an internal reform process, aiming at addressing the failures and weaknesses of the party. But instead of providing the party with new tools for handling internal and external opposition, it deepened divisions.

Emboldened by the youth protests, the internal division within the EPRDF culminated in the change of leadership within the ranks of the EPRDF in March 2018. The change of leadership was triggered by the decision of Prime Minister Haile Mariam Desalegn (successor of Meles Zenawi after his death in 2012) to resign from his position as party chair and prime minister in February 2018 as a part of the internal reform process. In March 2018, the EPRDF elected Abiy Ahmed to lead the party. He was confirmed prime minister in April 2018, the first ever national leader to come from the Oromo ethnic group. In this way, the Querro youth had one of their missions accomplished, to strengthen Oromo political influence at national level. In one way, this political change was indicating that youth activism actually has been heard at the national political scene. Since then, however, this has developed into a more complex relationship, where the new Prime Minister has de-emphasised the role of ethnic politics and demands, going for a broader pan-Ethiopian agenda, in many ways deceiving the ethnic-based youth agenda of the Querro.

Abiy Ahmed’s de-emphasis of ethnic politics also led to a radical re-organisation of the ethnic based ruling party, unifying the four ethnic based front into one, national Prosperity Party. This unification was strongly opposed by the TPLF. The acrimonious relationship that emerged between the TPLF and the federal government (Prosperity Party) culminated in an open military conflict since November 2019. The conflict in Tigray which is still unfolding will have major consequences for the youth. On the one hand, the main actors in the conflict are recruiting a large number of youths to their ranks. The war will have also socio-economic impacts. In this respect, many development programmes including youth employment schemes could be scaled down due to limited finances.

5.3. Post-2018 Changes and Continuities

Since April 2018, the country is in a sort of a political transition. As part of the political reforms, opposition political movements, which were either operating outside of the country and/or engaged in an armed struggle, were allowed to operate within the country. As a result, political organizations like the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) and the former Patriotic Ginbot 7, which reconstituted itself as Ethiopian Citizens for Social Justice (in short Ezema) were allowed to operate within the country. While there are many encouraging signs regarding political liberalization in terms of freedom of association and speech, there are also worrying developments across the country. Inter-ethnic tensions and conflicts; political polarization and difficulties in the maintenance of law and order are some of the major challenges that the country faces.

The post-2018 political changes have immense impacts on the youth. On the one hand, the youth are credited for the changes. But on the other hand, there is a rise in youth violence. The youth are active in what the government calls irregular organizations which in some cases are armed. The post-2018 changes have also opened multi-layered contestations over a range of issues – territory, economic resources, political power and others. In addition to these, political parties and activists heavily compete for the support of the mobilized youth. For instance, political parties such as Abiy Ahmed’s Oromo branch of PP, the Oromo Federalist Congress (OFC), and the Oromo Liberation Front (OLF) compete to enlist the support of the Queero to their side. Similar kinds of contestations among political parties are expected in other cases as well. For instance, there is competition among the Amhara wing of the PP and the opposition National Movement for the Amhara (NAMA) to enlist the support of the Amhara Fano youth group. The ruling party which controls the state machinery similar to its predecessor, is expected to use youth employment schemes to buy political support and quell the mobilized youth. But the way the funds are distributed and urban land (in some cases sidewalks in urban areas) are given have created further tensions.

The first elections after the 2018 leadership change were held in June 2021. The elections were not held in Tigray due to the conflict there, and Oromo opposition parties (OFC and OLF) boycotted the elections saying that there were no conditions for free and fair elections. A large number of political parties took part in the elections. Both the ruling party and the opposition parties fielded young politicians. It is, however, too early to predict if the elections would help to channel youth political and economic demands into parliamentary politics.

6. Conclusions

The weak participation of the youth in politics in Ethiopia is conditioned by the country’s economy and political structures. The imperial regime that stayed in power for half a century claiming its power from the divine authority discouraged people to take part in politics. The youth were taught to accept the fact that political power emanated from God and not from society. Although the student movement contributed to a public awareness that political power could be contested, following the rise of the Derg to power in 1974, the youth who challenged the military government was ruthlessly suppressed.

The EPRDF era saw some improvements both in terms of economic growth and youth political participation. Still, there was a low level of youth involvement in important decision-making institutions, including within the party organisations. The opening up of multiparty politics in the country encouraged opposition parties to compete for political power. It provides political space for the youth to take part as voters and candidates both in the ruling party and in the opposition parties. However, the constitutional and institutional instruments allowing multiparty politics in most cases remained on paper and the practice was far from the constitutional ideals. All the election results held in the country are indicative of the absence of free, fair and democratic elections. The incumbent won all and even in some cases with a 100 percent win. The developmental state policy that was espoused by the government to take lead in development activities even allowed the government to control the economic resources to distribute to its supporters through patronage politics. This further excluded a substantial number of youths that were not party members or affiliated with the regime.

In the fluid politics of Ethiopia in the post-2018 period, the youth would remain important actors for several reasons including their sheer size, increased activism and involvement in violence. In addition, political parties and the government seek to entice the youth to their side. As a result, it is expected that both youth development programmes and institutions for youth representation will continue to be utilized by incumbent governments. In this way, major youth policies in Ethiopia may not actually empower the youth, but rather bind them in patronage relationships and thereby reinforce their marginalization.

References

Abbink, J. (2006) Discomfiture of Democracy? The 2005 Election Crisis in Ethiopia and Its Aftermath. African Affairs, 105/419. Pp. 173-199.

Abbink, J (2017) Paradoxes of electoral authoritarianism: the 2015 Ethiopian elections as hegemonic performance. Journal of Contemporary African Studies. Volume 35, No 3

ACLED, Country Report (2017) Popular Mobilization in Ethiopia: An Investigation of Activity from November 2015 to May 2017. Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project

Antenane Abeiy Ejigayehu (2017) Factors Affecting Performance of Micro and Small Enterprises in Addis Ababa: The Case of Addis Ketema Sub-City Administration (City Government of Addis Ababa). MA Thesis, Addis Ababa University.

Arriola, R. Leonardo (2013) Suppressing Protest during Electoral Crises: The Geographic Logic of Mass Arrests in Ethiopia.

Arriola, R. Leonardo and Terrence Lyons (2016) Ethiopia: The 100% Election. Journal of Democracy. Vol. 27, No.1. National Endowment for Democracy and Johns Hopkins University Press. Pp. 76-88.

Balsvik, Ronning Randi (2005) Haile Selassie’s Students: The Intellectual and Social Background to Revolution, 1952-1974. Addis Ababa University Press.

Di Nunzio, Marco (2015) What is the Alternative? Youth, Entrepreneurship and the Developmental State in Urban Ethiopia. Development and Change, 46(5). Pp. 1179-1200.

FDRE (1995) Constitution of the Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Proclamation No.1/1995. Federal Negarit Gazeta. 1st Year, No. 1.

FDRE, (2017), Ethiopian Youth Revolving Fund Establishment Proclamation No. 995/2017. Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, Federal Negarit Gazette, 23rd Year, No. 24.

Gebremariam, E.B. (2017), The Politics of Youth Employment and Policy Processes in Ethiopia; IDS Bulletin (Vol. 48, No.3)

Getinet Haile (2003) The Incidence of Youth Unemployment in Urban Ethiopia. Paper Presented at the 2nd International EAF Conference, Addis Ababa.

Hailai Abera et al. (2019) Contribution of Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs) to Income Generation, Employment and GDP: Case Study Ethiopia. Journal of Sustainable Development, Vol. 12, No. 3. Pp. 46-81.

Heinonen, Paula (2013), ‘Youth gangs and street children: culture, nurture and masculinity in Ethiopia’, Social identities, Volume 7

Kedir Assefa Tessema (2009) The Unfolding Trends and Consequences of Expanding Higher Education in Ethiopia: Massive Universities, Massive Challenges. Higher Education Quarterly, Vol. 63, No. 1. Pp. 29-45.

Mycock, A and J. Tonge (2012) ‘The Party Politics of Youth Citizenship and Democratic Engagement’ Parliamentary Affairs, Volume 65, Issue 1, , pp. 138–161,

Nigusse Woldemariam Reda and Mulugeta Tsegai Gebre-eyesus (2019) Graduate Unemployment in Ethiopia: The ‘Red Flag’ and Its Implications.

Solomon Mebrie (2018) Electoral Politics, Multi-Partism and the Quest for Political Community in Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of the Social Sciences and Humanities, Vol. 14, No. 2. Pp. 93-127.

Vaughan, S and K. Tronvoll (2003) The Culture of Power in Contemporary Ethiopian Political Life, Sida Studies Number 10, Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida)

Young, J. (1997) Peasant Revolution in Ethiopia: The Tigray People's Liberation Front, 1975–1991 Cambridge: Cambrigde University Press

Notes

[1] The project is funded by the Research Council of Norway’s Norglobal programme and runs from 2019 to 2023. The first working paper can be found here: https://www.cmi.no/publications/7000-managing-the-born-free-generation-zimbabwes-strategies-for-dealing-with-the-youth

[2] Emperor Haile Selassie ruled Ethiopia over forty years since his coronation in 1930. From 1916 to 1931, he was regent to Empress Zewditu.

[3] The Workers Party of Ethiopia (WPE) was established under the chairmanship Colonel Mengistu Haile Mariam in 1984. It was recognized as a vanguard Marxist Leninist party by the 1987 Constitution of People’s Democratic Republic of Ethiopia (PDRE).

[4] The EPRDF that governed Ethiopia between 1991 and 2019 was a coalition of four ethnic based movements, namely, the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), the Amhara National Democratic Movement (ANDM) which in 2018 renamed itself to Amhara Democratic Party (ADP), the Oromo People Democratic Organization (OPDO) which in 2018 renamed itself as Oromo Democratic Party (ODP), and the Southern Ethiopian People's Democratic Movement (SEPDM). In December 2019, the three member organizations with the exception of TPLF were unified and formed the currently ruling Prosperity Party (PP).