Temporal governance, protection elsewhere and the ‘good’ refugee: a study of the shrinking scope of asylum within the UK

2. The legal framework for refugee protection

2.1.1 The proposed two-tiered approach

2.1.2 Protection through third-country resettlement and other controlled channels

2.1.2.1 Ad hoc relocation initiatives

3. The ‘hostile environment’ and earned protection

3.1 The broader hostile environment

3.2 The hostility of the British asylum system

3.3 How the hostile environment affects refugees

4. The mechanisms of precarious protection

4.1.1 From permanent to probationary residence (1998-2005)

4.1.2 Reinforcing safe return reviews (2016-2021)

4.1.3 The criteria for cessation of refugee status

4.1.4 Temporary residence and the right to private and family life

4.2.1 After settlement status: indefinite insecurity?

4.3 Obstacles to earned citizenship

4.3.1 Refugees and the good character requirement

How to cite this publication:

Jessica Schultz, Esra Kaytaz (2021). Temporal governance, protection elsewhere and the ‘good’ refugee: a study of the shrinking scope of asylum within the UK. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI Report 2021:06)

In recent years European countries have introduced increasingly temporary terms of asylum for people with a recognized need for protection. This study traces the temporary turn in the UK, where asylum policies have traditionally focused more on preventing new arrivals than on limiting the rights of people with refugee status.

Refugees in the UK experience insecurity of status stemming from the broader ‘hostile environment’ aimed at ‘bogus’ asylum seekers and irregularised migrants. Infractions such as illegal entry and unauthorized labour can sabotage efforts to secure permanent residence years down the line. Refugees are also subject to specific policies, including safe return reviews, after a probationary period of residence is over. Application of the internal relocation principle and broad inadmissibility criteria mean that refugees may be ‘returned’ to unfamiliar areas of their home country or third countries to which they have no meaningful ties. Finally, this study highlighted barriers to citizenship, including the ‘good character’ requirement, that affect refugees in particular ways.

The New Plan for Immigration, along with the measures to implement it proposed in the Nationality and Borders Bill, would punish refugees who arrive seeking asylum by imposing a longer path to settlement and denying them public support. These policies collapse the temporal and spatial dimensions of border control, subjecting ‘inadmissible’ refugees resident in the UK to prolonged temporary status and violating their rights under international refugee law.

Abbreviations

ACRS – Afghan Citizens Resettlement Scheme

ARAP – Afghan Relocations and Assistance Policy

CJEU – Court of Justice of the European Union

CRC – Convention on the Rights of the Child

DFID – Department for International Development

EC – European Commission

ECHR – European Convention on Human Rights

ECtHR – European Court of Human Rights

IA – Immigration Act

ILR – Indefinite leave to remain

IPA – Internal protection alternative

IR – Immigration Rules

LEC – Locally Employed Civilians

MoD – Ministry of Defence

RC – Refugee Convention

RIES – Refugee Integration and Employment Service

SSHD – Secretary of State for the Home Department

QD – Qualification Directive of the Common European Asylum System

UKHO – UK Home Office

UKRS – UK Resettlement Scheme

UKVI – UK Visa and Immigration

UNHCR – United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees

VPRS – Vulnerable Persons Resettlement Scheme

The authors would like to thank Eric Fripp, Melanie Griffiths, Katharine Jones, and Sheona York for generously sharing their insights with us during our research for this study. The analysis in this report covers developments in immigration and asylum policy as of November 2021. At the time of writing, the Nationality and Borders Bill was under review by Parliament, at the Report Stage during which further amendments may be proposed.

1. Introduction

This report is a mapping study produced through the project Temporary Protection as a Durable Solution? The ‘return turn’ in European asylum law and policies (TemPro).

The TemPro project aims to create new knowledge about the dynamics and effects of asylum policies reinforcing the temporary nature of protection provided to refugees. While in previous decades, temporary protection served as an exceptional response to large-scale refugee arrivals, current practices of temporary protection are embedded in the regular practice of refugee law. Strategies include the use of temporary permits combined with restricted rights to family reunification, active protection reviews, and more indirectly, barriers to permanent residence.

Refugee status is not meant to last indefinitely. The 1951 Convention on the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol (Refugee Convention) secures a form of surrogate protection in a third state for people compelled to leave their homes for their safety. Unless and until return is viable, states must facilitate refugees’ inclusion in their host communities by extending, inter alia, rights to property, education, labour and welfare. Refugee status is subject to withdrawal (‘cessation’) if a refugee either voluntarily avails herself of another state’s protection, or when conditions have changed so that she no longer has a need for asylum (RC 1C(1)-(6)). In other words, refugee law strikes a balance between a secure residence in countries of refuge and the possibility for sustainable returns to the country of origin. Temporary asylum policies, in contrast, typically involve limited rights in countries of refuge, and they may compel repatriation to countries at least partly in conflict.

Within Europe, the ‘summer of migration’ in 2015 fuelled restrictive measures on the part of affected states to deflect and deter refugee claims. Many countries adapted or intensified national-level policies of temporary protection to signal their reluctance to offer long-term refuge. In the UK, however, policy responses focused more on preventing migration from continental Europe than on diluting the terms of asylum for those who arrive. Moreover, they were embedded in the well-established ‘hostile environment’ policies which targeted asylum seekers as well as irregularised migrants. Even the most explicit policy of temporary protection, the ‘new temporary protection status’ proposed as part of the New Plan for Immigration in March 2021 (UKHO 2021a) (henceforth, the New Plan), was not justified primarily by a dramatic increase in refugee claims. Instead, it reflects the hardening of a distinction present in the asylum discourse for decades, between ‘bogus asylum seekers’ who claim protection upon or after arrival in the UK, and those refugees who access resettlement programmes and other controlled channels. In other words, the decision of who receives temporary status is not based on why that person has come, but how. According to the New Plan, ‘vulnerable refugees’ with a ‘genuine need’ that come by ‘safe and legal’ means would receive indefinite leave to remain (ILR) upon arrival while those who ‘enter illegally by paying people smugglers’ will be punished with time-limited permits and minimal public support. Many of the New Plan’s proposals are reflected in the Nationality and Borders Bill 2021, which opens for differential treatment among refugees depending on their mode of arrival (section 2.1.1).

Related to this distinction between deserving refugees and suspect asylum seekers are measures to delink migration and settlement in the UK. Policies of earned settlement frame permanent residence and citizenship as rewards rather than as means to support greater inclusion (Da Lomba 2010; Kapoor & Narkowicz 2019; UKBA 2008). A migrant’s disproportionate exposure to police contact (section 3.3), the criminalisation of unauthorised arrival and illegal work, and the possibility of falling out of status at some point due to high costs and complex rules, can sabotage efforts to secure ILR/settlement years down the line. When it comes to naturalisation, the ‘good character’ requirement also excludes refugees with associations to suspect organisations in their countries of origin – even if these were involuntary on the part of applicant.

The specificity of UK refugee policy has practical implications for the scope of this study. First, we note that recognised refugees get caught in wider efforts to deter and remove unwanted migrants. This requires us to expand the focus of our inquiry beyond refugee-specific policies to understand how, on the one hand, deterrence measures aimed at migrants in general affect opportunities for refugees in particular to receive permanent residence. On the other hand, we explore how policies expanding the scope for revoking settlement status for anyone with a migrant background particularly affects refugees. As this mapping will be followed by qualitative research into the experience of temporariness by refugees in the UK, casting a broad net permits a more inductive approach. Although it is tempting to focus on the temporal duration of a specific status or permit, this may or may not be the most important trigger of insecurity for research participants.

2. The legal framework for refugee protection

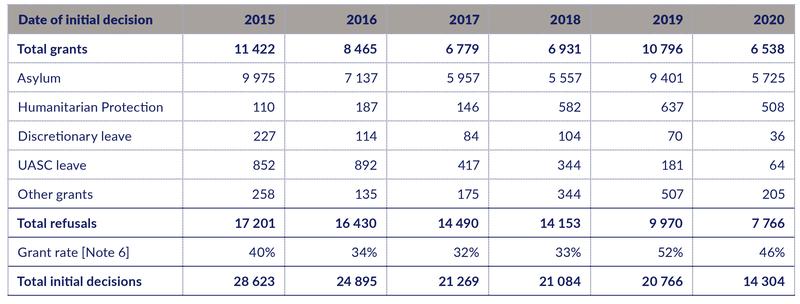

In the UK, the Home Office is responsible for immigration, asylum, and nationality laws and their implementation. Despite serious hurdles resulting from successive cuts in legal aid services, appeals against a negative asylum decision may be dealt with by the Immigration Tribunals (the First-tier Tribunal and Upper Tribunal). Further appeals may reach the Court of Appeals and, eventually, the UK Supreme Court. For the past decade, between a third and half of all asylum claimants have been granted asylum, humanitarian protection or alternative forms of leave in the first instance (with acceptance rates highest in recent years), while the final success rate increases by about 10–20 percent following an appeal. A large majority of those with a recognised need for protection (82 percent) are given asylum (refugee status).

The law that these bodies apply is anything but clear and coherent. Asylum and immigration applications are governed by a ‘byzantine’ collection of statutes, regulations and Home Office guidance that frequently change and mystify even well-seasoned judges and expert practitioners. Since the Asylum and Immigration Appeals Act of 1993, both Conservative and Labour governments have sought to restrict refugee arrivals through successive statutes that expand grounds for inadmissibility, limit rights to appeal, and reduce access to work and social support for asylum seekers: the Asylum and Immigration Act (1996); the Immigration and Asylum Act (1999), the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act (2002), the Asylum and Immigration (Treatment of Claimants etc) Act (2004), the Immigration, Asylum and Nationality Act (2006), and the Immigration Acts of 2014 and 2016. The Nationality and Borders Bill of 2021 continues this tradition.

This patchwork of primary legislation is supplemented by the 1000 + page Immigration Rules (IR), in addition to copious Home Office Guidance. The most important international sources of protection include the Refugee Convention (RC) which the UK ratified in 1954, as well as the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). The Refugee Convention is indirectly incorporated into UK law through Section 2 of the 1993 Act: ‘(n)othing in the immigration rules … shall lay down any practice which would be contrary to the Convention. The UK has also ratified the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), which means that best interests of children must be a guiding principle in all proceedings affecting them. This principle is codified in Section 55 of the Borders, Citizenship and Immigration Act 2009, which establishes a mandatory duty on the part of immigration officials to safeguard and promote the welfare of children in the UK.

Until the UK left the EU on December 31, 2020, it was bound by the Qualification Directive of the Common European Asylum System (QD 2004), which establishes regional criteria for granting international protection. Following Brexit this is no longer the case. Still, although the Nationality and Borders Bill revokes the implementing legislation for QD 2004, it so far retains the main categories of international protection elaborated in the Directive. In addition to refugee status, the Immigration Rules retain a category of ‘humanitarian protection’ for persons who face torture, inhuman and degrading treatment or punishment in violation of Article 3 ECHR as well as those whose risk of serious harm stems from indiscriminate violence in their countries of origin (IR para. 339C). There is also a separate temporary protection category in UK law as an emergency response to large-scale arrivals (IR paras. 355-356). This is distinct from the temporary protection previously granted refugees fleeing for example the Balkan wars in the 1990s, who received leave to enter the UK ‘outside the immigration rules’ for an initial period of 6 months and extended every 12 months by the Home Office until return was deemed viable (Humanitarian Issues Working Group 1995).

In January 2021, the UK announced new inadmissibility rules (IR paras. 345A-345D) to replace the Dublin Regulation, which sets out criteria for determining the state responsible for an asylum claim in Europe. These rules suggest a broad scope for refusing to assess an asylum application, permitting a finding of inadmissibility based on mere presence in, or connection to, a safe third country ‘even if that particular country will not immediately agree to the person’s return.’ In that case, removal is permitted to any safe third country that will admit them. As described in the New Plan:

Anyone who arrives into the UK illegally - where they could reasonably have claimed asylum in another safe country - will be considered inadmissible to the asylum system, consistent with the Refugee Convention … Contingent on securing returns agreements, we will seek to rapidly return inadmissible asylum seekers to the safe country of most recent embarkation. We will also pursue agreements to effect removals to alternative safe third countries (UKHO 2021a: 19).

Refugees who are deemed inadmissible but cannot, for legal or logistical reasons, be removed, may receive a temporary leave to remain in the UK (UKHO 2021a: 20). Far from increasing the efficiency of returns, these rules expose refugee claimants to longer periods of uncertainty as they wait for Home Office officials to canvas whether there are other countries willing to receive them.

2.1 Refugee status

Persons who meet the Refugee Convention criteria receive refugee status in the UK provided that no exclusion clauses (owing to security or criminal issues) apply (IR paras. 334, 339AA-AC). In accordance with Article 1A(2) of the Refugee Convention, refugees are persons who, ‘owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country.’

Currently, persons with refugee status receive a 5-year residence permit before they can apply for indefinite leave to remain. Refugees have full access to the National Health Service, social benefits, education, and the labour market. Under family reunion rules, they may be joined by close family members: spouses, minor children, civil partners, same sex, and unmarried partners who formed part of the family unit in the country of origin before the refugee left to seek protection (IR paras. 352A-F). Unlike other family immigration cases, there is no requirement that the primary applicant can secure adequate accommodation and maintain his or her relatives without recourse to welfare support.

Refugees may apply for a Convention Travel Document to travel outside the UK. A refugee integration loan is also available to persons with refugee or humanitarian status. Refugees are classified as ‘home students’ for the purpose of higher education degrees. This means that they avoid international fees and can access student loans from the time they are recognised.

2.1.1 The proposed two-tiered approach

Controversially, the New Plan for Immigration introduced a distinction in the type of protection granted based on a refugee’s mode of arrival. Similar to the Australian model, it aims to deter refugees from coming to the UK on their own by penalising ‘illegal’ arrivals with more tenuous terms of protection. Those who arrive through authorised channels would be rewarded with secure residence and other important benefits (including the potential for more generous family reunification rules).

The Nationality and Borders Bill translates this intention into legislation by enumerating two categories of refugees whose protection needs engage the UK’s obligations under the Refugee Convention. ‘Group 1 refugees’ must ‘have come to the United Kingdom directly from a country or territory where their life or freedom was threatened (in the sense of Article 1 of the Refugee Convention), have presented themselves without delay to the authorities and, if he or she entered irregularly must “show good cause” for having done so.’ Group 2 refugees, in contrast, are those that have not met these conditions.

This distinction is based on Article 31(1) of the Refugee Convention, which is generally understood to prohibit the penalisation (both criminal and otherwise) of refugees who enter or arrive irregularly. Exceptions are narrow, for example if the refugee already has asylum in a country of transit (Costello et. al. 2017). According to the Bill, however, refugees who transited through another country where they could have sought asylum fall into Group 2 (Clause 34). Illegal entry itself is criminalised, punishable by a prison sentence of up to 12 months (Clause 37).

In violation of the UK’s obligations under the RC, the Bill authorises the Secretary of State to penalise these ‘inadmissible’ refugees for their unauthorised mode of arrival by granting less favourable terms of residence. It provides that differential treatment can relate to the length of permission to remain in the UK; the criteria for qualifying for indefinite leave to remain; access to public support; and rights to family reunification (Clause 10). UNCHR has pointed out that these conditions breach duties of non-discrimination (Art. 14 ECHR and Art. 3 RC) as well as Article 23 RC, which requires state parties to provide refugees with public relief and assistance on par with nationals (UNHCR 2021).

In terms of the length of leave to remain, the New Plan signals an intention to grant temporary protection (up to 30 months at a time), after which the refugee is expected to leave the UK unless the basis for asylum remains (UKHO 2021a: 20). In the meantime, the need to apply for renewal every 30 months increases the practical and emotional barriers to inclusion for those with long-term needs for protection (section 4.1.2). Insecurity of status is intensified by the lowered threshold for expulsion on account of ‘serious crimes,’ so that crimes punishable with imprisonment for 12 months or more – like that of ‘illegal’ entry – may be the basis for removal (Clause 35).

2.1.2 Protection through third-country resettlement and other controlled channels

A small proportion of refugees are pre-screened by the UK government as part of several third-country resettlement schemes it operates with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the International Organization for Migration (IOM). Resettled refugees are usually recognised as Convention refugees with the rights and benefits that attach to that status.

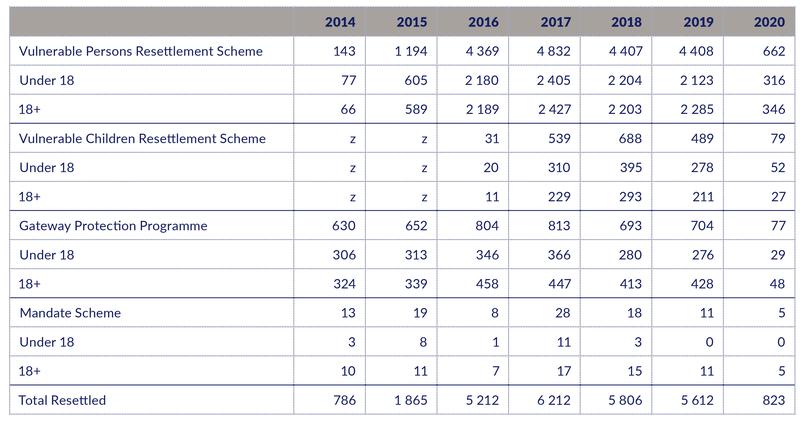

Between 2014 and 2020, 25,967 refugees were resettled under three main programmes: the Vulnerable Persons Resettlement Scheme (VPRS), the Vulnerable Children’s Resettlement Scheme and the 2004 Gateway Protection Programme, which aimed to resettle 750 refugees annually in ‘protracted displacement’. There is also a Mandate Refugee Scheme which settles refugees who have close families in the UK and who can accommodate them. The Vulnerable Persons Resettlement Scheme (VPRS) was the largest; it was initially established in 2014 as a joint initiative of the Home Office, the Department for International Development (DfID) and the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government. The aim was to resettle 20,000 vulnerable refugees displaced as a result of the Syrian conflict by 2020. As of June 2020, 20,007 had arrived in the UK (Walsh 2021). In 2019, the UK government announced its intention to consolidate these various schemes into a new global resettlement programme, the UK Resettlement Scheme (UKRS) (Gower 2021). The Covid-19 pandemic largely stopped resettlement during 2020, and the UKRS did not launch until 2021.

In addition to the UKRS, resettlement channels include the Community Sponsorship Scheme and the Mandate Refugee Scheme, which unites refugees with close family members in the UK willing to accommodate them. As described below, specific programmes to receive Afghan nationals in need of protection were created following the Taliban takeover.

To discourage people from coming to the UK on their own to seek asylum, the New Plan for Immigration commits to continuing refugee resettlement, including for refugees with needed skills to come through the points-based system. It also states the government’s intention to consider resettling refugees directly from their countries of origin; to grant resettled refugees immediate indefinite leave to remain; and to provide resettled refugees enhanced integration support and possibly more generous opportunities for family reunion. For example, the New Plan promises to explore the possibility of expanding the right to family reunification for resettled refugees to include adult children between 18 and 21 years old (UKHO 2021a: 13). It would also improve integration support to resettled refugees, including through expanded community sponsorship schemes.

2.1.2.1 Ad hoc relocation initiatives

In August 2021, the UK government announced the Afghan Citizens’ Resettlement Scheme (ACRS) for up to 20,000 Afghan nationals who have assisted UK efforts or are otherwise particularly in need of protection: human rights defenders, women and girls at risk, LGBT+, and members of ethnic and religious minorities. Afghans resettled through the ACRS will receive indefinite leave to remain in the UK and will be able to apply for British citizenship after 5 years of residence. With the launch of ‘Operation Warm Welcome’ in August 2021, Afghans under both schemes receive permanent residence, and promised support for housing, healthcare, and education, including free English language instruction. Meanwhile, Afghans who were either already in the UK or who may come on their own accord in the future are subject to the same punitive system as asylum seekers from other countries of origin.

A separate programme, the Afghan Relocations and Assistance Policy (ARAP) scheme was launched in April 2021 and provides relocation and other assistance to Afghans locally employed by the UK government, together with their families (MoD 2021). Prior to the ARAP scheme, there were two programmes under which Afghans who worked for the British government were eligible for relocation: an ‘Ex-Gratia’ scheme for locally employed civilians (LECs) made redundant as a withdrawal of the British Army in 2012 and an ‘intimidation scheme’ launched in 2013. Both these programs were criticised for the scope of eligibility and the provisions for those who are relocated (e.g. House of Commons Defence Committee 2018). Although Afghan LECs apply for relocation under these schemes due to threat to their safety, these are immigration visas. LECs relocated under the redundancy scheme, for instance, were initially required to pay for their ILR permit until these fees were waived in 2018 under public pressure.

An earlier relocation effort is codified in Section 67 of the Immigration Act of 2016, the so-called ‘Dubs Amendment’ named after its sponsor Lord Alfred Dubs. The Dubs Amendment offered relocation opportunities for unaccompanied children in Europe. Although initially campaigners and Lord Dubs himself proposed that the scheme extend to 3000 minors, the government committed to relocating 480 children, which it fulfilled in July 2020 (UKVI 2020). Under this scheme minors who do not qualify for refugee status or humanitarian protection are given ’Section 67 Leave,’ which is similar to refugee status as it entitles the status holder to apply for ILR after five years of residence. A further Dubs Amendment to allow separated children to be reunited with family members in the UK was inserted into the EU Withdrawal Agreement but rejected by the government.

Between October 2016 and July 2017, the government also relocated 549 children with relatives in the UK from Calais. Those who were found not to qualify for refugee status or humanitarian protection received ‘Calais Leave’ which entitles the children to a five-year leave renewable for another five years (UKHO 2020d). After 10 years of continuous residence children who received Calais Leave will be able to apply for ILR.

Table 1. Resettlement in numbers (2014–2020)

Source: UK Home Office, Immigration Statistics year ending June 2021, Asylum and Resettlement – Summary Tables.

2.2 Humanitarian status

People who do not meet the criteria for refugee status under the Refugee Convention may receive humanitarian protection if they face a real risk of serious harm (torture, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment) in breach of Article 3 ECHR, or a serious and individual threat in the context of indiscriminate violence (IR para. 339C). Typically, humanitarian protection is granted to people fleeing conflict where no specific grounds of persecution apply.

Humanitarian protection (HP) was introduced in 2003 (when the category ‘Exceptional Leave to Remain’ was dissolved), and until 2005 people granted HP were given a three-year leave to remain, upon which they would qualify for settlement as long as their need for protection continued (Migration Watch 2003). HP holders now receive a five-year period of leave just like Convention refugees and have the same rights to family reunification. They enjoy an unrestricted right to employment, education, and social benefits, and can apply for refugee integration loans. In other words, they are formally on the same path to settlement as people with Convention refugee status – with the same practical obstacles.

However, there are some subtle but important differences between the two types of status. For example, it may be harder for humanitarian status holders to defend themselves against the criminal charge of illegal entry (section 4.3.1) than it is for Convention refugees, since only the latter have (for now) a statutory defence to this charge. Also, when considering the cessation of status, authorities are required to inform UNHCR and give the agency an opportunity to present its opinion (IR para. 358C). No such oversight is available to humanitarian protection holders.

2.3 Discretionary leave

Finally, asylum claimants who are not found to qualify for refugee or humanitarian status may be granted residence if their return would breach human rights. Discretionary leave covers medical cases and other ‘exceptional compassionate circumstances,’ where removal of a claimant would constitute inhuman or degrading treatment in violation of Article 3 ECHR, or a flagrant breach of other human rights (UKHO 2021b: 9-10). Discretionary leave may also be granted to victims of trafficking who cooperate with the police to pursue their traffickers. The length of discretionary leave depends on its justification. Since 2012, the standard grant of leave has been 30 months, a half-year less than the previous norm of 3 years. However, both shorter periods and, in exceptional cases including where best interests of children so dictate, longer periods of leave may be granted (UKHO 2021b: 6-7).

For victims of trafficking, the length of leave varies between one year and 30 months to assist with the police investigation (UKHO 2021b:20). In addition to their (normally) shorter period of initial leave, persons with discretionary leave also have a longer route to settlement. People granted three years according to pre-2012 rules could apply after six years. Since then, those with discretionary leave must complete a continuous period of at least 120 months’ residence (i.e. a total of ten years, normally consisting of four separate thirty month periods of leave) before qualifying for permanent settlement.

People with discretionary leave have the right to work and access public funds. However, they have no right to be joined by family members until they qualify for settlement, and they are excluded from student financing schemes (UKHO 2021b: 15).

Since 2013, unaccompanied minors who lack inadequate reception arrangements upon return to the country of origin have received a distinct status, outside the broader discretionary leave policy: UASC leave (IR para. 352ZC). In 2020, 65 children were granted leave on this basis. Unaccompanied minors receive a residence permit for up to three years, or until the age of 17.5, whichever is shorter.

Table 2. Initial decisions on asylum applications, by outcome, 2010 to year ending June 2021

Note that these decisions include the main applicant only, and reflect the outcome of initial decisions. The actual numbers of individuals granted protection or alternative forms of leave will be higher.Source: UK Home Office, Immigration Statistics Year Ending June 2021.

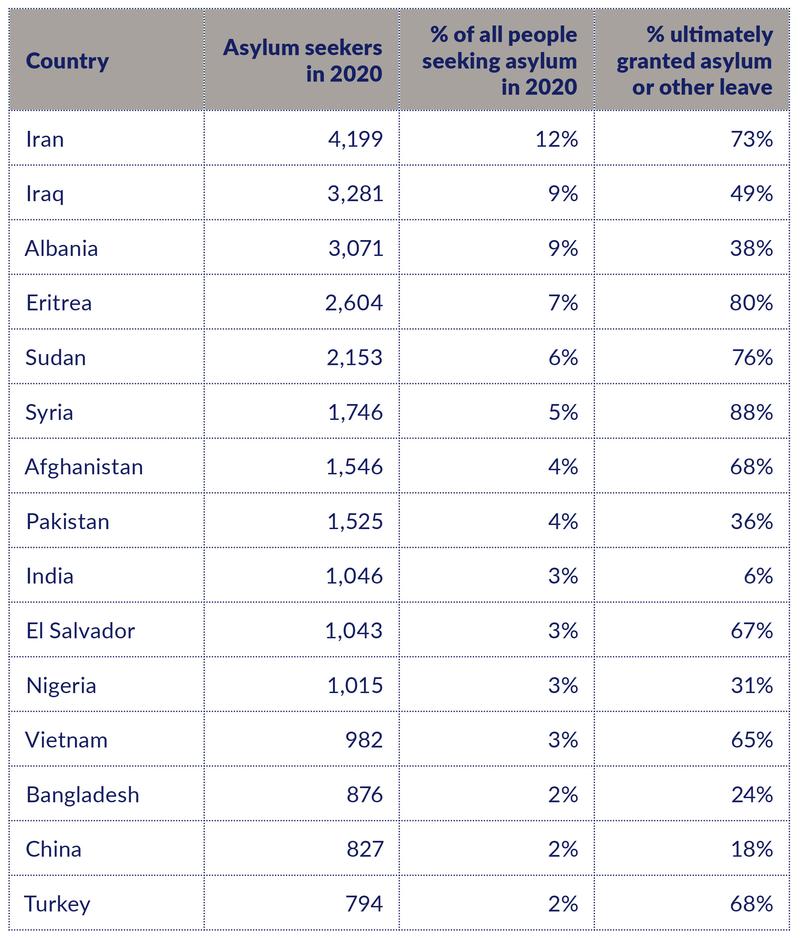

Table 3: Top 15 nationalities claiming asylum in the UK and grant rate, 2020

Source: Migration Observatory analysis of Home Office statistics

3. The ‘hostile environment’ and earned protection

The ‘hostile environment’ for migrants in the UK has implications for refugee protection and access to stable residence status. The following sections discuss how immigration policies which seek to punish irregularised migrants and ‘bogus asylum seekers’ also affect refugees with a recognised need for asylum.

3.1 The broader hostile environment

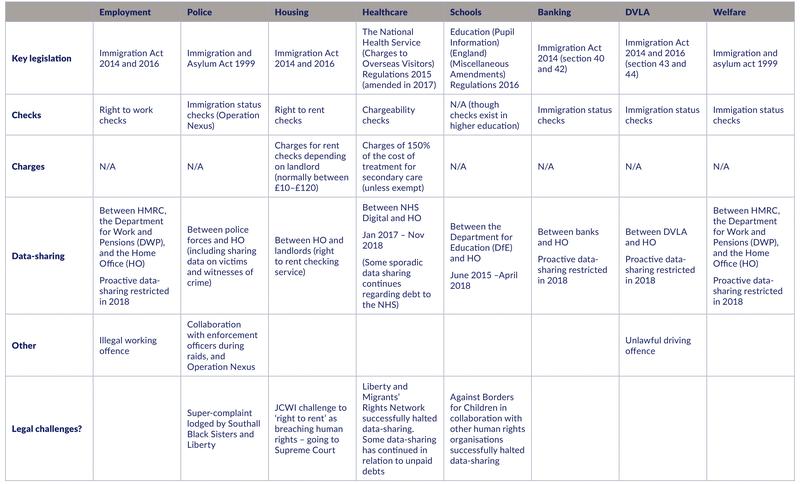

As an explicit policy objective, the aim to create ‘a really hostile environment for illegal migration’ was first announced by then-Home Secretary Theresa May in 2012. This phrase, ‘hostile environment,’ was extended from its original usage in the aftermath of 9/11 to manage the threat of terrorists in host countries, and its later application in the field of serious crime (Yeo 2020). In the immigration context, the ‘hostile environment’ similarly seeks to create an unwelcoming climate to deter undesirables from settling in the UK. In practical terms it involves a range of measures, such as data sharing between government forces and criminal sanctions on employers to meet ‘net migration’ targets for the UK. The Hostile Environment Working Group, later named the Inter-Ministerial Group on Migrants’ Access to Benefits and Public Services, is responsible for elaborating policies. When introducing legislative proposals for the future Immigration Act of 2014, the Immigration Minister Mark Harper described the overall purpose to ‘stop migrants using public services to which they are not entitled, reduce the pull factors which encourage people to come to the UK and make it easier to remove people who should not be here.’

The Act essentially requires citizens working in the health, banking, education, employment and housing sectors to carry out immigration checks on behalf of the Home Office while bearing sole brunt of hefty financial and legal penalties. This is an extension of the earlier carrier sanctions which require private companies to check the paperwork of passengers and the civil penalty regime for employers introduced in 2006 (Migrants Rights Network 2007). whereby border and immigration controls are outsourced and delegated to a range of public and private actors. Meanwhile, the Immigration Act of 2016 introduced the crime of ‘illegally working,’ which makes it offence for a person ‘subject to immigration control’ to work without permission, provided that he or she knew or had reasonable cause to have known that labour was unauthorised.

The hostile environment is a blunt tool that punishes many people, citizens, and migrants who have a right to be in the UK. Faced with significant penalties, employers, healthcare workers, landlords and others may target people they suspect may be non-citizens based on features such as appearance or name. As such they act on and entrench the racialised, gendered, and xenophobic prejudices of the immigration system that yielded these measures.

Table 4. The hostile environment in policies and practice

Source: IPPR analysis adapted from Liberty (2019), Patients not Passports (2020), Patel (2017), and Montemayor (2020).

The devastating impact of the hostile environment was brought to light through the Windrush Scandal (Gentleman 2019). Members and the children of the Windrush generation were unjustly accused of unlawful residence in the UK and threatened after the Home Office destroyed documents that proved their lawful residence. The moral outrage created by the scandal has not been sufficient to dismantle these practices. Sajid Javid who became Home Secretary in 2018 after the Windrush Scandal distanced himself from the Hostile Environment calling instead for a ‘compliant environment.’ Despite this change in official rhetoric, the structures and regulations that upheld the hostile environment remain albeit with some restrictions.

3.2 The hostility of the British asylum system

Although many current debates on asylum and migration take place under the banner of ‘hostile environment,’ hostility towards asylum seekers and refugees is nothing new. Restrictive and punitive policy aims have been central to British asylum legislation since the first asylum act in 1993 (e.g. Schuster 2003), reflecting a position held by some politicians and segments of the population that ‘bogus asylum seekers’ masquerade as refugee to access the UK’s welfare system. Successive governments have pursued restrictive and punitive policies targeted an ever more expansive category of ‘undeserving’ asylum seekers (e.g. Bloch and Schuster 2002; Schuster 2003; Sales 2002; Yeo 2020; York 2018). For example, the Section 55 Rules introduced in 2003 denied asylum seekers accommodation and support if they did not apply for asylum immediately upon arrival. This policy was reversed only after it was found to violate Article 3 of the ECHR. Similarly, the Asylum and Immigration Act of 2004 links a claimant’s overall credibility to when and where an application for asylum is made. For example, applying for asylum after the notification of an immigration decision (section 8(5)) or following an arrest for an immigration infraction (section 8(6)) can cast doubt on one’s credibility concerning the substance of a claim. The same is true following the failure to take ‘advantage of a reasonable opportunity to make an asylum claim or human rights claim while in a safe country’ (section 8(4)).

This ‘imposter until proven otherwise’ mentality (Yeo 2020) also motivates punitive policies directed at those who cross the English Channel such as harsh inadmissibility rules and ‘squalid’ conditions of detention while their asylum claims are decided – even during the Covid-19 pandemic. More generally, the hostile environment manifests in an obstructive bureaucratic culture and antagonistic narratives towards migrants that broadly infuse Home Office policies and practices (York 2018).

3.3 How the hostile environment affects refugees

While recognised refugees are not the main targets of the hostile or ‘compliant’ environment, they are affected by it in innumerable ways both directly and indirectly.

The long asylum case backlogs, and restrictions on freedom of movement and work prior to a decision make it difficult to achieve economic self-sufficiency when their claims are finally recognised. Newly recognised refugees have only 28 days, the ‘moving on’ period, before they are evicted from their government housing and lose their asylum support of about £5 a day (British Red Cross 2018). Many have exhausted any savings by this point and face homelessness. Further, delays in receiving national insurance numbers and biometric residence permits pose barriers to opening a bank account, looking for work, and applying for benefits. Women who were not the principal applicant on an asylum claim are disproportionately exposed to these problems (APPG 2017). When it comes to the integration loan available, the modest sums of money involved (around £500) and long processing times undermine its impact. The proposal in the Nationality and Borders Bill to deny many refugees access to social support threatens to further entrench this economic precarity.

One dimension of the hostile environment affecting refugees residing in the UK is the intersection of immigration and criminal law in efforts to remove undesirable people from British territory. Although the British Police Force have been involved in enforcing migration since the 1971 Immigration Act, which gave the police powers to check for passports, it was not until the launch of Operation Nexus in 2012 (Griffiths and Yeo 2021) that these powers were truly exploited.

Under Operation Nexus, immigration officers are embedded within police forces enabling them to carry out identity checks ‘in real time’ on persons in police custody. This means that anyone who has ‘contact’ with the police may be questioned. This record of contact is used to build cases of deportation (Griffiths 2017; Griffiths and Yeo 2021; Parmar 2020). Immigration officers can target foreign nationals with minor historic crimes, spent convictions and contact with the police including withdrawn charges and acquittals (Griffiths and Morgan 2017). Thus, ‘deportation can be justified through a medley of police encounters and arrests, even if they were for cautionable offences, made in error or did not lead to charge’ (Luqmani, Thompson and Partners 2014: 7 cited in Griffiths and Yeo 2021). Indeed, under Operation Nexus, victims of domestic abuse, trafficking and other vulnerable people have been apprehended due to their immigration status (Qureshi, Morris and Mort 2020; Liberty 2019) and are deterred from seeking protection. The explosion of potential fora for police-migrant contact has profound consequences for the possibility of attaining ILR and eventual citizenship (sections 4.2 and 4.3).

Refugees may be denied educational opportunities they are entitled to, especially while they are waiting for an asylum decision, because of institutional fears about complying with the required immigration checks (Ashlee and Gladwell 2020). Finally, even very minor mistakes navigating the immigration system, or failing to save enough for sudden increases in immigration fees, leads migrants to be ‘administered into illegality.’ This is compounded by the large gap between the demand and supply of legal assistance (Wilding, Mguni & Isacker 2021). Young persons who are ageing out of the system as their discretionary leave status comes to an end are particularly exposed to the possibility of becoming irregularised for periods of time.

Another consequence of the overall policy discourse is the downgrading of integration support for refugees after their status is recognised. Between 2008 and 2011, the Refugee Integration and Employment Service (RIES) programme helped newly recognised refugees access housing, education social security, and the job market. When this programme ended, it was replaced by a ‘postcode lottery’ in which levels of support depend on where the refugee happens to live (APPG 2017). In the New Plan for Immigration, the government has promise to continue supporting the Refugee Transitions Outcomes Fund, a recent initiative in a few pilot cities to facilitate integration through work placements, training programmes, and language classes (UKHO 2021a: 13). Still, at the national level programmes like Operation Warm Welcome and community sponsorship initiatives focus on the minority of refugees who arrive in the UK through controlled channels like third-country resettlement.

The day-to-day concerns of my partner are not the same as many other migrants. Many people are unaware that refugees cannot secure a mortgage until they get Indefinite Leave to Remain, so if a refugee has a job and tries to buy a house, they won’t be allowed a mortgage, unlike migrants with permanent residence.

The story of accommodation becomes even harder when a refugee wants to rent a house and presents a Residence Permit Card that states ‘refugee status.’ In many cases this triggers unconscious bias from landlords due to wrong stereotypes about refugees.

In finding jobs, refugees like many other migrants are seen as temporary residents, so they end up caught in the bureaucracy of the recruiter who might be looking at them as an unstable workforce. They also face the suspicion and stereotypes around refugees that can affect their applications.

Other refugees fear travelling during their refugee status because they fear hostility at airports when they show up with their refugee travel documents.

… All these factors cause the five-year temporary residency period of a refugee to be full of struggle, uncertainty and fear of the future.

Adam Mahran, “Give permanent residence to all refugees now,” Migrant Voice (guest article). Reprinted with permission by the author and Migrant Voice.

4. The mechanisms of precarious protection

Given the extensive backlogs of asylum cases at the Home Office, a positive decision on refugee status is often celebrated as the end of a stressful and prolonged process to establish one’s right to protection. As of July 2021, 1200 asylum seekers in the UK had been waiting for resolution of their case for more than five years, a third of these for more than a decade. Almost three quarters of asylum decisions take more than one year, a tenfold increase since 2010 (Refugee Council 2021: 1). Practitioners and other commentators have noted that the mechanisms proposed in the Nationality and Borders Bill, for example the new inadmissibility rules, are likely to increase rather than decrease the amount of time needed to determine a claim.

For many refugees, however, insecurity of residence remains long after asylum is granted. From a legal perspective there are at least three sources of persistent precarity: 1) the initial period of probationary residence and intensification of ‘safe return reviews’; 2) the requirements for settlement and citizenship which exclude refugees for a wide range of offences; and 3) obstacles to family reunification.

4.1 Safe return reviews

4.1.1 From permanent to probationary residence (1998-2005)

Earlier strategies to reduce inefficiencies in the asylum system saw immediate settlement as a solution rather than as a pull factor for more migrant arrivals. The Labour Government’s 1998 White Paper Faster, fairer, firmer: A modern approach to immigration and asylum noted that the large increase in asylum seekers during the previous decade (from 4000 to 32,000 a year) had put a ‘severe strain’ on the system (SSHD 1998: para. 3). To address this, one measure proposed was to abolish the four-year qualification period before a refugee can apply for ILR, and to reduce the same period for persons granted Exceptional Leave to Remain from seven years to four. Increased security of status would help refugees ‘integrate more easily and quickly into society, to the benefit of the whole community into which they have been accepted’ (SSHD 1998: para. 9.4). For a number of years, refugees granted refugee status in the UK were granted permanent residence as soon as they received a positive decision. People with humanitarian status would qualify for the same after four years.

By 2005, however, the Labour Government had changed its tune significantly. Its five-year immigration and asylum strategy, set out in Controlling our Borders: Making migration work for Britain, emphasised the need to ensure that long term settlement is ‘carefully controlled and provide(s) long term economic benefit’ (SSHD 2005: para. 35). To that end, applicants for ILR would need to pass a language and civics knowledge test along with other requirements (SSHD 2005: para. 39). Refugees, meanwhile, would be granted a five-year residence permit before becoming eligible. The right to settle was contingent on the lack of significant improvements in the refugee’s country of origin and, implicitly, evidence of good character since criminal convictions or deception in the immigration process would also be considered.

Research suggests that the additional insecurity caused by limited permits detrimentally affects employment, education, and health of refugees (Refugee Council 2010; Stewart & Mulvey 2014). For example, some employers have refused to invest in the training and hiring of people who are not certain to remain (Stewart & Mulvey 2014). However, the most disruptive aspects of this new probationary period were moderated during its first decade by the fact that most settlement applications, if made before the initial limited leave expired, were routinely approved. Refugees were only required to attest that they still faced persecution in their countries of origin. While information about criminality or dishonesty in the immigration process could trigger a more thorough review, the threat of nationality-based refusals based on improved conditions – which required a ministerial level declaration – never materialised.

4.1.2 Reinforcing safe return reviews (2016-2021)

Like other countries in Europe faced with large numbers of refugee arrivals in late 2015, the UK government responded with reinforced efforts to restrict asylum access – even though the ‘success’ of deterrence measures outside the country’s borders meant that relatively fewer refugees found their way to its shores (Yeo 2020). Among the restrictive measures proposed was a strengthening of the safe return review. As Home Secretary Theresa May explained to Conservative Party colleagues in 2015, this new policy would ensure that if a refugee’s ‘reasons for asylum no longer stands and it is now safe for them to return, we will seek to return them to their home country rather than offer settlement here in Britain.’ Active safe return reviews were introduced, according to the Home Office, in February 2016 (UKHO 2016).

This measure did not arise in a vacuum. The EU Qualification Directive has consistently endorsed the possibility of time-limited residence permits (QD 2004 and QD recast 2011). Accordingly, the current minimum requirement is to grant refugees and subsidiary protection beneficiaries permanent residence first after a period of five years. In 2016, moreover, the European Commission (EC) proposed reforms to the Common European Asylum System that include ‘systemic and regular checks’ to ensure that renewed residence is based on a continued need for protection (EC 2016: para. 11). Although new legislation has not been approved, the proposal underscores that such measures were part of regional dialogue (ECRE 2016).

Home Office guidance states that a settlement application may be refused if there has been ‘a significant and non-temporary change in country situation,’ a change in personal circumstances, or re-availment of protection by the home country as evidenced by return to that country or acquisition of a national passport (UKHO 2017: 11). As one informant explained, the ‘seemingly random questions about links to the home country’ on settlement applications heightens worries that any contact a refugee has had, no matter what the reason, may be held against her. Unlike the previous practice, this active review policy applies no matter when the application was made (before or after temporary leave expires). It may also be enforced in the absence of a settlement application, at the initiation of the government when a particular country is deemed safe for the return of its nationals or following allegations of fraud related to the grant of refugee status, travels to the country of origin, criminal activity or suspicious behaviour deemed a potential threat to UK security.

The two-tiered system outlined in the New Plan and the Nationality and Borders Bill on the one hand reverts to the previous policy of immediate settlement for resettled refugees, while refugees who seek asylum at the border or within the UK are subject to a new temporary status, with more frequent safe return reviews as periods of short-term leave expire. The insecurity produced by this policy, compounded by a prolonged path to permanent settlement, may cause or exacerbate mental and physical health problems, and intensify the barriers to housing, employment, and education that refugees without permanent residence already experience. Given the Home Office backlog, it is also conceivable that the safe return review process will create extended periods of being ‘out of status,’ particularly if the possibility of removal to other ‘safe’ countries with which a refugee may or may not have links, is also assessed.

4.1.3 The criteria for cessation of refugee status

Safe return reviews are linked with criteria for the cessation, or withdrawal, of refugee status under the 1951 Refugee Convention. While the Refugee Convention encourages state parties to facilitate the eventual naturalization of refugees (Art. 34 RC), it also gives states the right to cancel refugee status (when granted on fraudulent grounds), to revoke it (in cases of serious criminality), or to ‘cease’ or withdraw status when protection is no longer needed. Cessation criteria are set out in Article 1C of the Convention, and include voluntary acts on the part of the refugee (i.e. acquisition of a new nationality, acts that indicate that a refugee has re-availed him or herself of the home state’s protection) (Art. 1C (1)-(4) RC). It also, however, provides for cessation of status when the refugee ‘can no longer, because of the circumstances in connection with which he has been recognized as a refugee have ceased to exist, continue to refuse to avail himself of the protection of the country of his nationality’ or, in the case of stateless persons, the country of former habitual residence (Art. 1C (5)-(6) RC).

The UK Immigration Rules confirm, echoing EU standards in the Qualification Directive, that any change of circumstances must be significant and non-temporary in order to meet the cessation criteria (IR para. 339A). As Home Office guidance explains, ‘(t)he overthrow of one political party in favour of another might only be transitory or the change in regime may not mean that an individual is no longer at risk of persecution’ (UKHO 2021c: para. 4.2).

On the other hand, in UK practice, it is possible to find a ‘significant and non-temporary change’ in part of the country of origin, even if that part is an area in which the refugee has never before lived. Reliance on internal relocation (also known as the ‘internal protection alternative’ (IPA)) in the cessation context is controversial; UNHCR has consistently argued that dependence on an IPA indicates that changes in the country of origin are neither fundamental nor durable (UNHCR 2003). Further, the consequence of this practice is typically continued displacement within the country of origin, a result in tension with the duty to support durable solutions (UN Global Compact on Refugees; Schultz 2020). Potentially, this interpretation of cessation criteria opens the possibility for refugee returns to fragile, insecure countries already burdened by large populations of internally displaced residents, such as Afghanistan, Somalia, Syria, and Sudan. Important limitations have been clarified by the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) in a case referred by the UK – which ironically is not binding on the UK post-Brexit. In its judgment, the CJEU confirmed that financial and social support provided by private actors like clan or family members – either in the home area or in an IPA – does not constitute ‘protection’ for the purpose of withdrawing refugee status.

Safe return reviews, which canvas the possibility of internal relocation, underplay the refugee’s attachments in the country of residence while over-emphasizing attachments to the country of origin (or other countries) (Neylon 2019:3). This is predictably problematic for women refugees who may have a hard time proving their need for continued protection based on, for example, a risk of forced marriage or FGM years after the recognition of refugee status. Similarly, women may be disproportionately exposed to cessation for voluntary reattachments to the country of origin (RC Art. 1C(1)-(4)) because of caregiving obligations towards family members still living there.

4.1.3.1 A lower threshold for removing criminal refugees?

Under international refugee law, criminal refugees may lose the benefits of status under limited circumstances (serious offences or threats to national security) through post-hoc exclusion procedures resulting in ‘revocation’ of refugee status (RC Art. 33(2); UNHCR 2003: para. 6). The Nationality and Borders Bill would lower the threshold for revocation so that refugees who have been convicted and sentenced to 12 months’ imprisonment may be removed, compared to the existing requirement that the crime is punishable by a sentence of two years (Clause 35).

At the same time, as noted above, criminal records of any kind can also trigger a cessation review. In practice, it seems that cessation may be applied when the severity threshold for revocation on grounds of criminality or threats to public security cannot be met. According to a report by the Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration, the three Home Office units responsible for reviewing cases (Criminal Casework for foreign national offenders, the Special Cases Unit for persons posing a threat to national security and the Status Review Unit for anyone else with ILR, refugee status or British nationality) operate with different practices and little coordination when it comes to withdrawing residence permits (Bolt 2018). Between January 2015 and March 2017, for example, the Criminal Casework unit applied cessation to 309 persons, compared to 25 by the Status Review Unit (Bolt 2018: para 10.4). This suggests that cessation is being leveraged to deport refugees with lesser criminal records when the requirements for revocation cannot be met. Most refugees deported on this basis have come from Somalia, followed by Zimbabwe, the DRC and Afghanistan (Bolt 2018: para 10.6).

4.1.4 Temporary residence and the right to private and family life

The practical impact of a more active cessation practice is heightened by a restricted legal space for resisting an eventual deportation through an Article 8 claim. Article 8 ECHR, which protects the rights to private and family life, is commonly raised as a defence to deportation when the claimant has established relationships in the UK. According to caselaw of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) these rights are weaker for migrants without a valid residence permit compared to those who have permanent residence. The rationale applied is that irregularised migrants lack a justified expectation of stay, meaning that any private relationships they establish in the country of residence may be given less weight. A grey zone arises, meanwhile, for migrants with legal, but not permanent, residence (Schultz 2020). In the Rhuppiah v SSHD [2018] judgment, involving Article 8’s protection of the right to private life, the UK Supreme Court rejected the proposal to take a contextual approach to the notion of a ‘settled migrant’ which would consider the length of legal residence. Instead, it drew a bright line based on status, considering any permit less permanent than indefinite leave to remain to be ‘precarious’ and therefore not ‘settled.’ Given that many refugees may not qualify for, or be able to afford, settlement status even after years of legal residence, this position weakens protection of private relationships established in the UK. In cases involving minor children, a child’s best interests will typically not override the public interest in deporting the parents (UKHO 2021d: para. 7).

4.2 Barriers to settlement

The requirements for settlement for people with refugee or humanitarian status are set out in the Immigration Rules (IR 339R) and are elaborated in Home Office guidance (UKHO 2021d). In addition to the requirement of a continued need for protection, the Home Office retains a right to delay settlement for refugees with a criminal history or where evidence of behaviour that runs ‘counter to British values’ is produced (UKHO 2021d: 17). As earlier guidance explained, the purpose of this is to ‘ensure that war criminals and perpetrators of other serious criminal offences as well as those with a history of less serious criminality, cannot avoid the consequences of their actions’ and to ‘delay the path to settlement in the UK to those who have committed criminal offences or whose character, conduct or associations are considered not to be conducive to the public good’ (UKHO 2016: para. 1.3). Unlike other migrants (with some exceptions), refugees and humanitarian status holders are excluded from language and knowledge requirements for the purpose of settlement ‘in recognition of their continued need for protection’ (UKHO 2013: 7).

If a migrant has been convicted of an offence and sentenced to imprisonment for four years or longer, ILR must be refused (IR para. 339R iii(a)). Crimes with shorter sentences mean that the applicant must wait a certain number of years before a new application can be approved (IR para. 339R iii (b)-(c)). So for example, the criminal penalty of up to 12 months in prison for illegal entry proposed in the Nationality and Borders Bill would mean a seven-year delay in eligibility for ILR for refugees who are convicted. Further, admission or conviction of an offence within the two years prior to an application which resulted in a non-custodial sentence can also be the basis for refusing ILR, as can the determination that a person has ‘persistently offended and shown a particular disregard for the law’ (IR para. 339R iii (d)-(e)). Given migrants’ disproportionate exposure to interactions with the police (section 3.3), this vague and discretionary provision poses a significant risk for refugees who apply for permanent residence.

Refugees who do not receive ILR but who are determined to have a continued need for protection are granted further limited leave in periods of at least 30 months, following which they must apply either for ILR again or a renewal of their limited leave (UKHO 2021d: 27). When assessing each application, the Home Office will consider whether there are grounds for withdrawing their refugee status (UKHO 2021d: 20).

As mentioned above, the Nationality and Borders Bill authorises the Secretary of State or an immigration officer to impose a different route to settlement for ‘inadmissible’ refugees who cannot be removed to another country as it does to those who arrive through ‘lawful’ channels. While the latter may be rewarded with ILR at the outset, refugees in the former group have no clear path to permanent residence. Indeed, they potentially could be eligible first after a decade of continuous (and crime-free) stay under the 10-year route to settlement (IR para. 276B).

4.2.1 After settlement status: indefinite insecurity?

Changes made to the Immigration Act of 2014 expand the scope for migrants – including refugees – to lose their settlement status. Even after a refugee’s ILR application in the UK is approved, rights of residence may be revoked for reasons related to criminality, deception, or cessation of refugee status based on the refugee’s own acts indicating that he or she has re-availed themselves of another country’s protection (76(3) INA 2002; UKHO 2021c). While cessation in this context excludes political changes over which the refugee has no control, it implies that people who actively maintain transnational ties – and their dependents – risk losing the right to remain in the UK.

Regarding criminality, deportation of foreign criminals is deemed ‘conducive to the public good’ as a point of departure (Sec. 32 UK Borders Act 2007). While certain exceptions apply when deportation unduly infringes the rights to family and private life, the weight of the public interest in removing criminals has become increasingly important through subsequent legislation (117C IA 2014). Even if a deportation order is eventually revoked, the UK Supreme Court has held that settlement status need not be reinstated. Instead, periods of limited leave could be granted according to the situation.

4.3 Obstacles to earned citizenship

While the granting of a new citizenship is represented as the gold standard of security for someone displaced by war or persecution, the promise of a UK passport is muted by barriers like high fees, language and knowledge tests, and good character requirements designed to exclude ‘disobedient, transgressive, undeserving’ migrants from the benefits of UK nationality (Kapoor & Narkowicz 2019: 1). The good character requirement has become the main reason for denial of citizenship applications in recent years (Kapoor & Narkowicz 2019: 2). Further, as discussed below, the good character requirement particularly affects people with refugee backgrounds.

The good character requirement for all applicants over the age of ten was introduced in the British Nationality Act of 1981, which removed the automatic right of citizenship previously enjoyed by people born in the UK. In the Borders, Citizenship and Immigration Act of 2009, the concept of earned citizenship evolved further with a stricter evaluation of ‘character’ including criminality-related issues on the one hand and positive civil engagement (participation, paying taxes) on the other. While the Nationality Act itself does not define ‘good character,’ Home Office guidance provides insights into the kinds of conduct to be considered in the assessment, not only related to criminality but also financial soundness and attempts to deceive a government department (UKHO 2020a). This latter category includes illegal entry to the UK, assisting illegal migration, and immigration infractions including unauthorised work. But it can also be established through discrepancies in a person’s documentation, for example two different dates of birth. Technically, a Home Office official must be convinced ‘on the balance of probabilities’ that the applicant is of good character (UKHO 2020a: 8).

When it comes to criminality, an applicant will normally be refused if they have received a custodial sentence of at least four years; a sentence between one and four years unless a period of 15 years has passed since the sentence; a sentence of less than 12 months unless a period of ten years has passed since the end of a sentence; or a non-custodial sentence recorded on the criminal record within three years of the date of application (UKHO 2020a: 11-12). Further, as with applications for settlement, a decision-makers can justify a refusal on an ‘overall pattern of behaviour’ the individual elements of which would not be sufficiently serious. Negative factors are weighed more heavily than positive factors, and practice shows that thousands of children have been denied citizenship based on their (often minor) contact with the criminal justice system (Haque 2020:11).

4.3.1 Refugees and the good character requirement

Evidence suggests that persons refused citizenship on the basis of ‘bad character’ are most often refugees, from countries like Iraq and Afghanistan (Kapoor & Narkowicz 2019:9). Further, research points to two dimensions of the character requirement that closely connect to the refugee experience: 1) associations with actors in third countries deemed to be terrorists or responsible for crimes against humanity or war crimes, and 2) breaches of immigration law compelled by the asylum process itself.

When it comes to undesirable associations, there is no requirement that such attachments are current or even recent. Indeed, a refugee’s activities in the country of origin may come back to haunt her years later – even if they were not serious enough to exclude her from refugee status from the outset (RC Art. 1F). In SSHD v SK (Sri Lanka), the Court of Appeals determined that the applicant’s ‘substantial and voluntary’ involvement in the LTTE, which was responsible for war crimes, crimes against humanity and terrorist acts during the period of the time he was active could justify a refusal of citizenship. Meanwhile, in SSHD v DA (Iran), the Court concluded that, although the applicant was involuntarily conscripted into military service in Iran, his failure to disassociate himself from human rights abuses committed by the military could be construed as evidence of bad character. Women tend to risk the stamp of ‘bad character’ not because of their direct activities but through their associations to friends and family members (Kapoor & Narcowicz 2019: 14).

With regard to immigration infractions, citizenship refusal letters commonly cite ‘detected working’ as a reason, based on information declared in the application or received from other sources. Unauthorised labour includes any job taken while waiting for an asylum decision or during gaps in legal residence, for example if a refugee allows her original leave to expire before applying for settlement. These between-status periods, and any income earned during this time, may be held against her even if there are good reasons for missing the deadline.

Refugees are also hard hit by changes introduced in Home Office guidance in 2014 that made illegal entry during the previous ten years relevant to the good character requirement. Even if defences are theoretically available (one based on RC Art. 31(3) used mainly for false passport offences and one based on a reasonable excuse for failing to produce a passport at all), refugees may not have been properly advised to raise a defence and end up with a custodial sentence.

Current ‘good character’ guidance instructs officials to take account of Article 31 of the Refugee Convention when considering whether it is appropriate to refuse (citizenship) to a person granted refugee status on the grounds of illegal entry’ (UKHO 2020a: 47). Nonetheless, the Home Office retains significant discretion in cases where the asylum seeker did not promptly apply for asylum or took a circuitous route to the UK. The guidance states that a person who enters the UK illegally with the intention of claiming asylum should do so within four weeks of arrival unless there is a reasonable explanation for the delay. This timeframe is problematically short, particularly since the date of the asylum claim is set at time of the screening interview – which can itself take weeks to arrange.

Scrutiny of a refugee’s travel route, meanwhile, stems from ‘an expectation that those seeking protection should do so in the first available safe country, so should not, for example, travel across several European countries to claim in the UK’ (UKHO 2020a: 47). If the applicant arrived in the UK via other countries, this may ‘cast doubt on an applicant’s good character.’

This default position of scepticism signals a shift from the context-specific approach to secondary movement endorsed by the High Court in 2001. In the Adimi judgment, Lord Justice Brown found it relevant to consider the length of stay in the intermediate country, the reasons for delay there (even a substantial delay in an unsafe third country would be reasonable were the time spent trying to acquire the means of travelling on), and whether or not the refugee sought or found protection de jure or de facto from the persecution they were fleeing. Today, meanwhile, the mere fact of secondary movement may exclude someone from admission to the UK, or undermine an application for naturalisation years down the road.

4.4 Separated families as a source of insecurity

Refugees and humanitarian status holders can apply for family reunification to be reunited with minor children and spouses from family formed pre-flight. The ordinary requirements including visa fees and a minimum income do not apply. In order to be reunited with other family members, however, such as adult dependents, ‘post-flight’ partners, or adult relatives of minors with refugee or humanitarian status, the sponsor must provide accommodation, have a minimum income, and pay visa fees as well as health surcharges. In these cases, the sponsor must also be able to support the family member until he or she finds work or qualifies for public funds. These financial barriers mean that many families remain separated in practice (Borelli et al 2021).

Until recently, family members had to travel to Visa Application Centres (VACs) in person to submit the documents necessary and wait while a decision is made. This added costs and exposed family members to additional vulnerabilities, especially if they had protection claims them or were prevented from returning to their previous residence, for example in a refugee camp (British Red Cross 2020). Following recommendations made by the Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Migration, as of spring 2019 applicants can submit their application online and only need to travel to the VAC if their application has been accepted (Bolt 2020: 14). Still, waiting times due to the Covid-19 pandemic remain a serious hurdle, with a 94% drop family reunion visas issued in June 2020. Refugees are also affected by broader changes following Brexit, because family members in the EU who would previously been able to apply to join families in the UK under Dublin III are no longer permitted to do so. The government has only committed to putting in place a system for unaccompanied children in the EU to join relatives lawfully resident in the UK, and vice versa (Gower and McGuinness 2020).

The New Plan for Immigration promised to consider widening the definition of ‘family’ for resettled refugees to include children under the age of 21 (instead of 18). The Nationality and Borders Bill does not refer to this promise but introduces the possibility for the differential treatment of the family members of Group 1 refugees from Group 2 refugees whereby the latter would have limited rights to reunification. In June 2021, Baroness Ludford introduced the Refugees (Family Reunion) Bill to expand the definition of family to include, for instance, unmarried children and siblings under the age of 25, and to make legal aid for family reunification available to refugees and humanitarian status holders.

Family members are entitled to the same rights and services as their sponsors (‘leave in line’) but do not have refugee status or humanitarian protection (‘status in line’) (UKHO 2020b: 25). As such their stay in the UK depends on the status of the sponsor even though they may have fled the same circumstances. This raises concerns about the security of residence and unmet claims of protection from pre-flight spouses and children, as well as post-flight families (e.g. Borelli et. al. 2021).

5. Conclusion

In contrast to policies pursued elsewhere in Europe, which grant subsidiary protection holders fewer rights than Convention refugees, asylum policies in the UK distinguish less between the reasons for a refugee’s need for protection than on his or her mode of arrival. Decades of anti-migrant measures have hardened the distinction between ‘bogus asylum seekers’ who come to the UK by boat or in the back of a lorry, and ‘vulnerable’ refugees who wait patiently in refugee camps for a chance at resettlement. The temporary status outlined in the New Plan for Immigration (2021) mirrors the Australian approach by extending externalisation policies to people who have already arrived in the UK.

The New Plan for Immigration, along with the measures to implement it proposed in the Nationality and Borders Bill, discriminates among refugees with similar needs for protection by punishing those who arrive seeking asylum. It criminalises ‘illegal’ entry; limits access to family reunification, withholds rights to public support, and prolongs the path to permanent residence. These policies further subject ‘inadmissible’ refugees to indefinite insecurity through regular reviews of their right to remain. Residence may be withdrawn not only if conditions in their countries of origin change, but also if any safe third country, potentially in exchange for financial support, is willing to receive them. These punitive measures are clearly at odds not only with the obligations voluntarily assumed by the UK government under the Refugee Convention and other human rights instruments, but also as signatory to the Global Compact on Refugees. Efforts to outsource asylum and exclude refugees within the UK sit uneasily with the duties to promote durable solutions and to share responsibility for providing protection.

Until the New Plan was announced, temporary protection was not an explicit focus of the UK’s restrictive refugee policies. While a probationary period of residence has existed since 2005, most of the insecurity associated with refugee status has stemmed from a broader logic of earned residence that affects not only refugees but migrants more generally. The constant need to prove one’s belonging is a key feature of the ‘hostile environment’ and reinforces a ‘continuum of precarity’ (Neylon 2019) that starts at arrival, particularly for those who claim asylum, and persists through various stages of residence status.

Refugees who arrive as asylum seekers have long been disadvantaged when it comes to legal, social, and economic security. Asylum seekers are subject to detention, excluded from the labour force and receive minimal public support, sometimes for years, while waiting for their asylum decision. Their illegal entry to the UK can be leveraged years later as evidence of ‘bad character,’ as can their engagement in unauthorised work or indeed any police contact no matter what the motivation or outcome.

The stability of refugee status is also undermined by measures that increase the revocability of residence, including broad definitions of criminal behaviour and ‘safe return reviews’ after a probationary period has ended. This means that refugees must prove that they have a continued threat of persecution or serious harm in their countries of origin, which may be difficult for victims (often women) of non-state or even private persecutors. Application of the internal relocation principle and expansive inadmissibility criteria mean that refugees may be ‘returned’ to unfamiliar areas of their home country or third countries to which they have no meaningful ties. Family reunification rules extend less security to partners and children, who often have their own protection needs. Finally, this study highlighted the ways in which refugees are disproportionately affected by the ‘good character’ criteria for citizenship not only because of infractions incurred while waiting for an asylum decision but also because of activities or associations in the country of origin even if these were involuntary.

With the proposal to create a distinct temporary protection status for refugees who arrive using unauthorised channels, UK authorities have merged existing temporal techniques of internal bordering (time limits and safe return reviews) with spatial techniques of external bordering (containment, the two-tier system of protection, and safe third country rules). The irony of course is that this ‘return turn’ in asylum policy is completely disassociated from return realities, meaning that the compression of protection space will predictably extend rather than reduce asylum processing times, and prolong the hardships of being displaced.

References

All-Party Parliamentary Group. 2017. Refugees Welcome? The Experience of New Refugees in the UK. April 2017. https://refugeecouncil.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/APPG_on_Refugees_-_Refugees_Welcome_report.pdf.

Ashlee, Amy, and Catherine Gladwell. 2020. Education Transitions for Refugee and Asylum-seeking Young People in the UK: Exploring the Journey to Further and Higher Education. Refugee Education UK (formerly Refugee Support Network) for Unicef UK (London). https://downloads.unicef.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Education-Transitions-UK-Refugee-Report.pdf.

Bloch, Alice, and Liza Schuster. 2002. “Asylum And Welfare: Contemporary Debates.” Critical Social Policy 22 (3): 393-414. https://doi.org/10.1177/026101830202200302. https://doi.org/10.1177/026101830202200302.

Bolt, David. 2018. An Inspection of the Review and Removal of Immigration, Refugee and Citizenship “Status”. (April – August 2017). Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Migration. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/677535/An_inspection_of_the_review_and_removal_of_immigration_refugee_and_citizenship__status_.pdf.

–––. 2020. An `Inspection of Family Reunion Applications (June – December 2019). October 2020. Independent Chief Inspector of Borders and Immigration. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/924812/An_inspection_of_family_reunion_applications___June___December_2019.pdf.

Borelli, Silvia, Fiona Cameron, Elena Gualco, and Claudia Zugno. 2021. Refugee Family Reunification in the UK: Challenges and Prospects. Centre for Research in Law (CRiL), University of Bedfordshire in partnership with Families Together. https://familiestogether.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Refugee-Family-Reunification-in-the-UK-challenges-and-prospects.pdf.

Brekke, Jan-Paul, Jens Vedsted-Hansen and Rebecca Stern. 2020. Temporary Asylum and Cessation of Refugee Status in Scandinavia. EMN Norway Occasional Papers. https://www.samfunnsforskning.no/aktuelt/arrangementer/2020/filsamling/emn -occasional-paper- temporary-asylum-and-cessation-of-refugee-status-in-scandinavia-2020-1.pdf.