The cost of doing politics in Uganda: Perspectives on violence against political candidates

Political conflicts and violence in Uganda

Surveying political candidates in Uganda

What does political violence look like in Uganda?

Timing and location of political violence

How to cite this publication:

Matthew Gichohi, Gerald Kagambirwe Karyeija, Stella Kyohairwe, Vibeke Wang, Pär Zetterberg (2025). The cost of doing politics in Uganda: Perspectives on violence against political candidates. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI Brief 2025:05)

Uganda’s politics is characterized by the normalization of violence as a routine part of elections. Most candidates experience violence, mainly psychological, often perpetrated by leaders, members, or supporters of other parties. Such incidents occur mostly during campaigns and on election day, with many going unreported, reinforcing the view that violence is simply part of doing politics in Uganda.

Key takeaways

Most Ugandan political candidates have experienced some form of violence. It has been almost normalized as a component of electoral politics

- Male – compared to female – candidates are more exposed to almost all forms of violence, with the most frequent form being psychological in nature.

- The most common perpetrators of violence are leaders/members/supporters of other parties.

- Most violent incidents take place during the campaign phase, followed by election day.

- Political parties took action in 59% of the cases of violent incidents reported, but nearly half of violent incidents remain unreported to the party.

Political conflicts and violence in Uganda

After assuming power in 1986, having been in a five-year guerrilla war as a result of losing the 1980 elections, Yoweri K. Museveni’s National Resistance Movement (NRM) regime adopted a distinctive 'no-party' system. Political parties were suspended from participating in elections and in the period from 1986 to 2006, candidates were elected based on individual merit within the broad Movement framework. Social inclusion of marginalized groups such as women were emphasized by introducing a system of reserved seats. After a 20 year no-party rule, a referendum for restoring multiparty politics was held in Uganda on 28 July 2005 with more than 90% voters backing the return of multiparty politics. A multiparty system was restored in February 2006 and the NRM transformed into the biggest political party[1]. General elections have been held in 2006, 2011, 2016, and 2021 under a multiparty dispensation.

Since 2006, violence against opposition politicians has escalated. In the 2006 elections, Kizza Besigye of the Forum for Democratic Change was arrested on charges widely regarded as politically motivated. During the 2011 "Walk to Work" protests, security forces killed several protesters and arrested opposition leaders (Goodfellow, 2014). During the 2018 Arua by-election, opposition candidate Robert Kyagulanyi (Bobi Wine) and others were brutally beaten and charged. In the 2021 elections, widespread detentions, torture, and killings followed the arrest of Bobi Wine. The Uganda People’s Defence Forces, Uganda Police Force and other security organs have been deployed to suppress opposition rallies. The Public Order Management Act (2013) institutionalized this militarization, giving police authority to approve or deny public gatherings.

Surveying political candidates in Uganda

Uganda uses a simple plurality electoral system for the elections to the legislative assembly (exceptions include indirect elections of special group representatives, including 5 youth, 5 workers, 5 persons with disabilities, 5 older persons, 10 army representatives and 4 representatives of the eldery). A reserved-seat quota for women was introduced already in 1989: one woman representative per district is elected by universal adult suffrage in a separate election. The number of district women representatives in parliament has increased in tandem with the creation of new districts (from 79 in 2006 to 146 in 2011). No new districts have been created since 2011. The total number of women in parliament has increased from 102 in 2006 to 189 in 2021, with only 16 women being elected in constituency competitions against men in the most recent election.[2] Currently, women make up 34% of Parliament (2021-2026), which comprises 557 representatives of whom the majority are constituency representatives (353 representatives). Although there is evidence that the quota policy has had positive effects (Clayton et al. 2018), the policy has also helped reinforce NRM dominance (Muriaas and Wang, 2012).

We surveyed 1,006 candidates (out of the total number of candidates that contested the 2016 (1,747) and 2021 (2,659) legislative elections).[3] The analysis used in this brief relies on 977 observations because 29 of them were miscoded. We used clustered sampling with 611 men and 366 women and included both elected (328) and non-elected candidates (649). The proportion of women here is slightly higher (6%) than the number of seats they hold in parliament. 40% of candidates interviewed were youth, meaning that they were under the age of 40, the region´s cut off for such a designation. Given the presence of reserved seats for women, the sample also includes 180 (18%) candidates who competed for these positions. Candidates were interviewed either face-to-face or via phone call by enumerators from Ace Policy Research Institute (Kampala). They used electronic tablets equipped with the Open Data Kit.

What does political violence look like in Uganda?

Violence against politicians in Uganda takes several forms. Here, we focus on candidates´experience of psychological, physical and sexual violence. Psychological violence is the behavior that causes mental distress or undermine´s the candidate´s dignity. It manifests through threats, intimidation, character assassination, stalking or even online abuse. Physical violence involves the intentional use of physical force to cause harm or injury. Sexual violence, has both a physical and psychological component, as it includes such acts as sexual harassment, unwanted advances, sexual assault and rape.

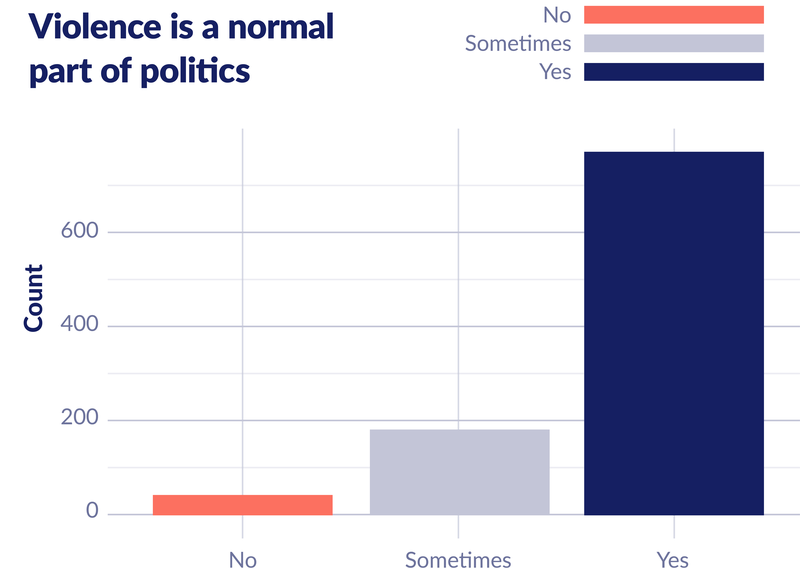

The scope and form of these types of violence in Uganda remain an empirical question. Our data shows that political violence is normalized (Fig.1); 95% of candidates interviewed believe that violence is a normal aspect of Ugandan politics. Of those interviewed, 90% have experienced some form of violence (physical and/or psychological).

Figure 1: Number of candidates who perceive violence as being a normal part of politics.

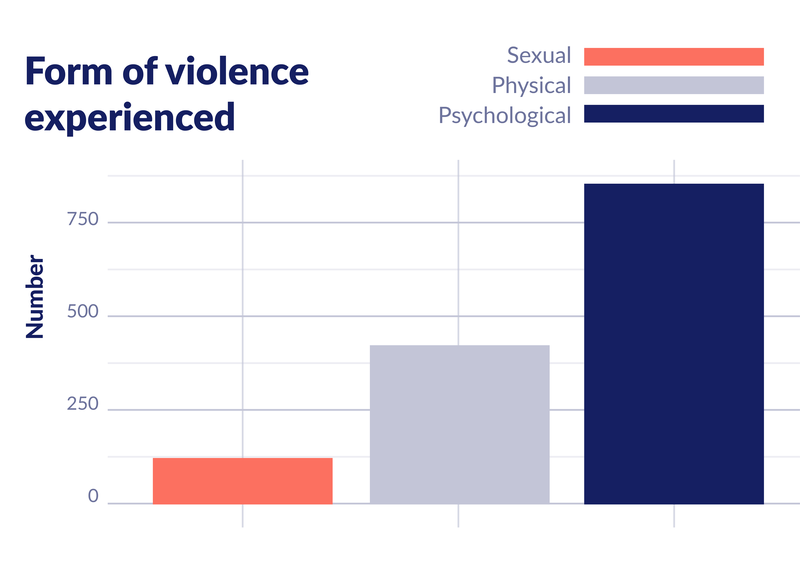

Physical violence is prevalent with 44% (426 candidates) of the sample reporting some experience with it: 50% of men and 33% of women candidates interviewed suffered physical violence. The most frequent form of violence meted out against candidates appears to be psychological in nature. 89% of candidates interviewed were subject to some form of psychological violence. Sexually connoted violence seems to occur at lower rates than either physical or psychological violence. 14% (n=128) of candidates state that they experienced this kind of violence.

Figure 2: Number of each type of violence experienced by politicians in the sample

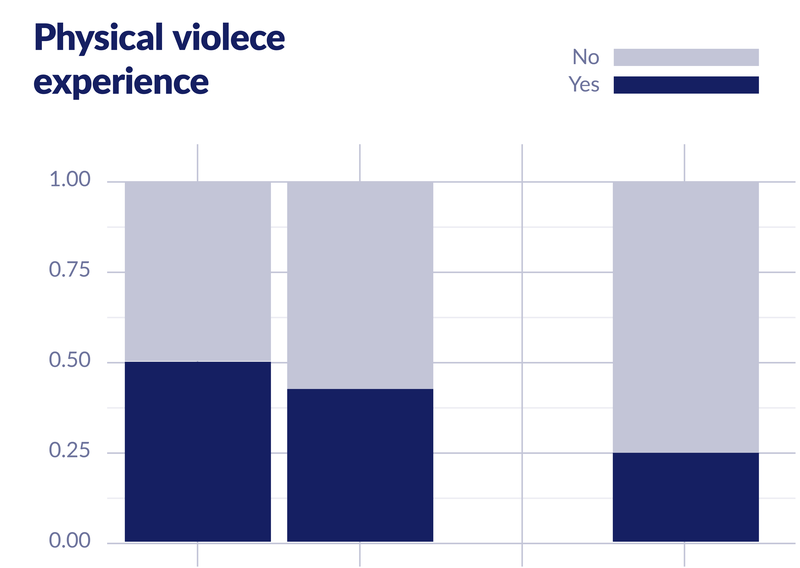

In considering whether competing in reserved seats protects women from violence, we see that it does not entirely do so. The data shows that though sexual and physical violence does occur at lower rates than in open seats, violence still occurs. Psychological violence affects candidates in both open and reserved seats at significant rates. More than 75% of candidates, regardless of sex, in both seat types experience psychological violence. Considering the relative sizes of the groups, women in constituency seats face more violence than those competing in reserved seat races.

Figure 3: Experience of physical violence by electoral seat type

Sources of political violence

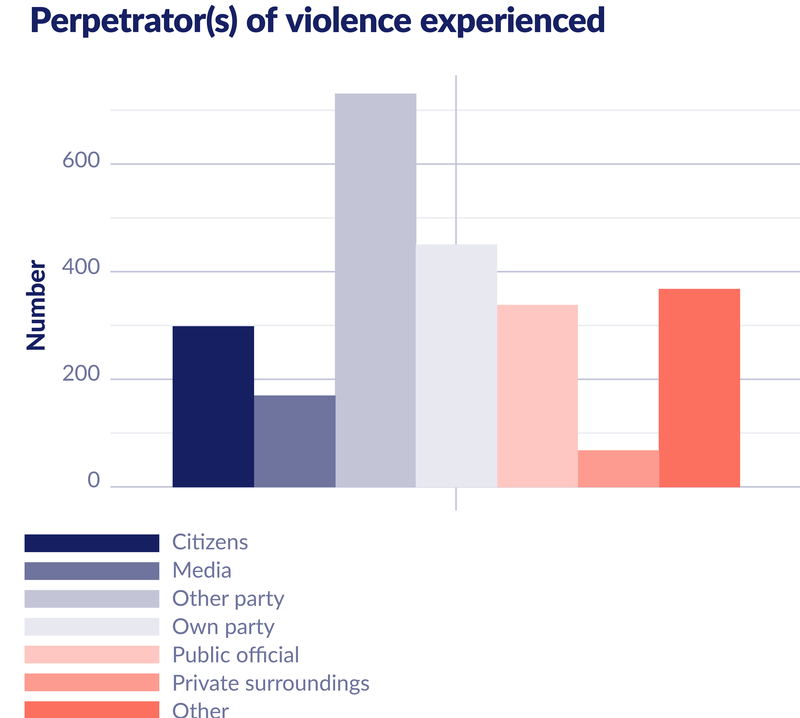

The most common perpetrators of violence are leaders/members/supporters of other parties, followed by leaders/members/supporters of the candidate´s own party. This pattern is similar regardless of whether the victim is a man or a woman. The third most common perpetrator of violence against candidates are the “other” group, a category that includes hired thugs and militant groups. Public officials mete out violence against candidates at almost similar rates as hired thugs. Family and friends, who comprise the private surrounding category, are responsible for the least amount of violence experienced by candidates.

Figure 4: Number of perpetrators who mete out violence against politicians (Alternative to the top plot)

Timing and location of political violence

Most violent incidents take place during the campaign phase, followed by election day. Almost an equal amount of violence is experienced in the nomination and post-election phase. Unsurprisingly, the least violence is experienced during parliamentary sessions.

There are no big gender differences. Slightly more men (89%) than women (82%) have experienced violence in the campaign phase as well as in the nomination phase (38% vs 36%).

When we asked where the physical violence took place, we found that more men than women experienced physical violence at political events (26% men vs 18% women), in public (21% men vs 13% women), and at home (6% men vs 3.6% women).

Party action

96% of the candidates’ were aware of their party having ethical guidelines in place. A bit more than half of violent incidents (51%) were reported to the party organization. There are some differences in the types of violence reported to the party: psychological violence 58%, physical violence 73%, and sexual violence 52%. Men, it seems, were more likely to report violent incidents to their party structures. Among men, 55% reported their experiences of violence to the party, compared to 46% of women. If the incident was reported, the party took action in 59% of the cases. Looking at the party´s response to each type of violence, our data shows that physical violence was responded to 39% of the time, while 41% of the psychologically and sexually violence incidents reported were addressed by the party. The parties appear to be more responsive when men report than women. Yet nearly half of violent incidents remain unreported.

Consequences of political violence

Experiences of violence seem to affect politicians in unexpected ways. Political candidates who have experienced violence are more likely to run for office again. Rather than have a negative and cowering effect, violence appears to embolden candidates and make them more resilient. It is no surprise, however, given the party inaction discussed earlier, that those who experience violence feel less proud of their parties. These patterns hold regardless of the candidate’s sex. More information is, however, needed to better understand these unexpected results.

In the next phase of the project, we will collect qualitative data to help us interpret our findings. Yet, we caution against taking the results to imply that violent experiences are positive. In contexts where violence is normalized and therefore to be expected by candidates, violent incidents may be considered as just the cost of doing politics. Following this logic, experiencing violent incidents may confirm to candidates that they are a force to be reckoned with by political opponents. Yet, the normalization of violence may also pose a considerable barrier to entering politics and act as a bottleneck in the recruitment process. Who are the people who self-select into politics under the current circumstances and equally important, who do not, due to the high costs of engaging, enter politics?

References

Becker G. S ., (1958) Democracy and competion. Journal of Lay and Economics, 1 pp 105-109

Clayton, Amanda, Cecilia Josefsson and Vibeke Wang (2018) “Quotas and women’s substantive representation: Evidence from a content analysis of Ugandan plenary debates.” Politics and Gender 13(2): 276-304.

Carbone, G. M. (2003). Political Parties in a ‘No-Party Democracy’ Hegemony and Opposition Under ‘Movement Democracy’in Uganda. Party Politics, 9(4), 485-501.

Goodfellow, T. (2014) “Legal manoeuvres and violence: Law making, protest and semi-

authoritarianism in Ugand” Development and Change, 45(4): 753-776.

Hodges, D. C., (1965) Political Democracy: Its Informal Content. The American Journal of Economics and Sociology Vol. 24, No. 1 (Jan., 1965), pp. 9-20 (12 pages)

Kyohairwe B. S (2010). Gendering political institutions in Uganda: Opportunities, significance and challenges of women in local politics. VDM Publishing.

Lipset .S., and Rokkan, S . “ Cleavage structures, Party system, and voter alignment” . An Introductin in Lipset & Rokkan, eds. Party Systems and and voter alignments. Free Press. NY 1967

Makara, Sabiti and Vibeke Wang (2023) “Uganda: A Story of Persistent Autocratic Rule.” In Leonardo R. Arriola, Lise Rakner, and Nicolas van de Walle eds., Democratic Backsliding in Africa? Autocratization, Resilience, and Contention. Oxford University Press, pp. 212-234.

Makara, S. (2009). The challenge of building strong political parties for democratic governance in Uganda: Does multiparty politics have a future?. Les Cahiers d’Afrique de l’Est/The East African Review, (41), 43-80.

McGuire. J., (2014) Democracy, Agency and the Classification of Political Regimes,” In Brinks. D; Leiras. M; and Mainwaring. S; eds. Reflections on Uneven Democracies: The Legacy of Guillermo O’Donnell, 2014. Johns Hopkins University Press

Morlino, L. (2004). What is a ‘good’democracy?. Democratization, 11(5), 10-32.

Muriaas, Ragnhild and Vibeke Wang (2012) “Executive dominance and the politics of quota representation in Uganda.” Journal of Modern African Studies 50(2): 309-338.

Mwenda, Andrew (2007) “Personalizing power in Uganda.” Journal of Democracy 18(3): 23-28.

Tripp, Aili Mari (2010) Museveni’s Uganda. Paradoxes of Power in a Hybrid Regime, London: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Tripp, A. M. (2012). Women and politics in Uganda. University of Wisconsin Pres.

Notes

[1] By calling itself an organisation, NRM honours its Movement legacy and projects itself as a unifying force, even as it fully engages in Uganda’s party‐based democracy

[2] Of the 175 remaining women, 146 are District Women Representatives, 14 ex-officio members, 3 Female Army Reps, 2 female workers reps, 3 persons with disabilities, and 3 older persons reps.

[3] In 2021, 86 women were nominated to compete for directly contested seats against men, while 636 were nominated to run in the reserved seats.