Shutting down social media, shutting out the youth?

Young people, social media, and politics

States deploy various techniques to control online activities

How online controls affect younger and older citizens’ use of social media for news

How to cite this publication:

Pauline Lemaire (2023). Shutting down social media, shutting out the youth? Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI Brief 2023:4)

Young people across Africa use social media to participate in politics, while their governments implement strategies to limit online political mobilization. However, young citizens whose government shut down social media use social media to get the news more. This phenomenon is even stronger for older citizens. This is important, as new African users join an online environment marred by state control. Digital literacy will ensure that citizens can leverage social media for politics.

Key messages

- While social media represent an important tool for youth political engagement across the African continent, states have deployed an array of strategies to limit the reach of social media.

- Using social media comes at a high cost: cost of the device, cost of data, including in some cases heavy taxes. This might explain why we see older citizens increasingly using social media to get the news in countries that see higher levels of social media shutdown, compared to young citizens.

- Donor organisations should consider the strategies of control of social media deployed by states when funding interventions aiming at enhancing freedom of expression and political participation.

- Civil society organisations should continue focusing their efforts on digital literacy, including the use of circumvention tools.

Summary

Young people across Africa use social media to participate in politics, while their governments implement strategies to limit the political mobilization via social media. However, young citizens whose government shut down social media actually use social media to get the news more than those of countries who do not. This phenomenon is even stronger for older citizens. This is particularly important, as the African continent experiences constant and meaningful growth in terms of internet users. These new users join an online environment marred by shutdowns and other forms of state control. Digital literacy, especially learning to bypass blockings, plays an important role in ensuring that citizens can leverage social media to exercise their fundamental political rights.

Social media have been an empowering tool for youth, enabling them to access information, discuss politics and mobilise for protests.

Young people, social media, and politics

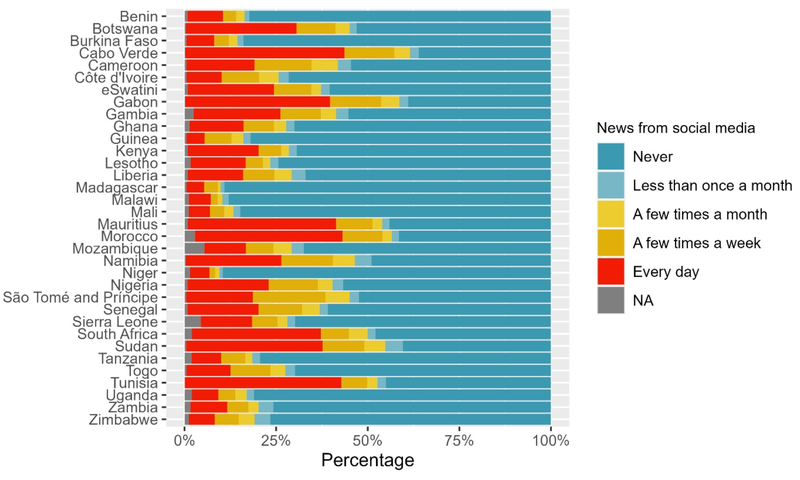

Young people are defined by the African Union to be aged between 18 and 35. This takes into account the breadth of ‘youth’ across the continent, where the ‘young’ are often dependent upon their families while looking for employment. Young people are considered as the early adopters of social media, and new technologies in general. Young African activists have leveraged social media – among other tools - to mobilize against authoritarian regimes, in countries across the continent. While young people, for example, in Guinea protesting increased taxes on internet data were unsuccessful, others, as in Sudan or Tunisia during the Arab Spring, have contributed to overthrowing the dictator. Social media has been an empowering tool for youth, enabling them to access information, discuss politics and mobilise for protests. The extent to which young people’s use of social media differs from that of older people is however unclear. The proportion of African citizens (all age categories included) who regularly gets the news from social media across the African continent remains limited. According to data from the Afrobarometer, there are only a few countries where at least 50% of the population uses social media to get the news a few times a month or more. It is also important to note that internet and social media are only a feature of urban areas. In most rural areas, internet remains unavailable.

African states, particularly the most autocratic ones, have deployed a large range of techniques aiming at controlling online political activities.

States deploy various techniques to control online activities

African states, particularly the most autocratic ones, have deployed a large range of techniques aimed at controlling online political activities. Such techniques can be more or less visible for users. For example, shutting down access to all social media, as was the case at the end of the campaign to the 2021 general elections in Uganda is an extremely visible form of control. Facebook remains inaccessible to this day in Uganda, unless one uses dedicated tools to bypass the blockage, such as a Virtual Private Network (VPN). In this case, all social media users directly experience state control, as they have to actively use a circumvention tool to access the service.

Source: Data from the 7th round of the Afrobarometer (survey filed in 2016–2018).

There is some evidence from other contexts that very visible tools of control, such as social media shutdowns, can lead to a form of backlash. For example, when the Chinese government shut down Instagram for its citizens, researchers observed a significant increase in the number of downloads of VPN, and of another long-blocked social media: Facebook. Shutting down social media can lead to citizens starting to use circumvention tools, like VPNs, or to starting using social media to get the news when services become accessible again. In fact, the introduction of a tax on social media use in Uganda in 2018 led to an increase in the use of VPNs in Uganda.

Other techniques are much less visible to users. For example, although it is known that some African states like Uganda use surveillance software such as ‘Pegasus’, enabling them to monitor the activities of the individuals they target, it is very difficult to know who is under surveillance, or to identify that one has been targeted by such surveillance. Beyond surveillance, other less visible techniques include state manipulation of online content, for example by pushing automatically generated posts – or posts produced by paid individuals - to bury critical messages and make them very hard to access for users. Such manipulation is extremely difficult for users to identify.

African states also introduce legislation and taxation to severely repress online freedom of expression and information, as in the case of Tanzania, where the definition for cybercrime is very broad, and bloggers have to register with the state. This type of legislation creates fear among bloggers and leads to self-censorship, or what can be called a chilling effect. Another example is the use of high taxes on access to social media (for example in Uganda between 2018-2021) or on internet data, as seen in Uganda since 2021, or in Guinea among others. These tools are visible when they are first implemented, but their visibility to all users diminishes over time, once protests against their implementation are over. While the tax on social media in Uganda led to some users adopting VPNs to avoid paying the tax, it also leads to the number of social media users dropping. When costs become high, users who cannot pay or use circumvention techniques are simply excluded.

African countries who shut social media might experience a form of backlash, at least in the forms of citizens using of social media for news more.

How online controls affect younger and older citizens’ use of social media for news

To evaluate how social media shutdowns affect younger and older citizens differently, statistical analyses are run based on data from the Digital Society Project, included in the Varieties of Democracy project, and data from the Afrobarometer’s seventh round. These analyses show that older citizens (above 35 years old) use social media significantly more in countries that implement social media shutdowns, even when accounting for non-visible forms of control such as surveillance or state online content manipulation. It is however important to note that younger citizens in countries that rely on social media shutdowns also use social media for news slightly more.

The analysis, combined with evidence from other studies, shows that African countries which shut down social media might experience backlash, at least in the form of citizens relying more on social media as a news source, especially older citizens. Two mechanisms can be at play. Firstly, as social media users adopt circumvention tools, such as VPNs, to bypass shutdowns, and as these tools are costly, the older group are more likely to afford the related costs. Secondly (older) citizens who were not already getting news from social media start doing so once the shutdown is over, as the shutdown signals that interesting things are happening on social media.

The opposite phenomenon could also be taking place: states shut down social media because a wider portion of society, and in particular older citizens, use social media for news. However, the results presented here have also taken into consideration other forms of social media control. If states control social media more when they are used more, then the other forms of control should also be positively related to the use of social media for news. As they are not, it is more likely that African countries which shut down social media experience backlash from their citizens.

Recommendations

- Governments should refrain from shutting down access to social media or internet.

- Donor organisations should consider the strategies of control of social media deployed by states when funding interventions aiming at enhancing freedom of expression and political participation.

- Civil society organisation should continue focusing their efforts on digital literacy, including the use of circumvention tools.

- Interventions should target both younger and older age groups, as overall the use of social media for news remains low across the African continent.

- Donors and civil society organisations should not rely solely on social media or internet for their interventions, as these only reach a small section of the population.

Further readings

Allen, N., & La Lime, M. (2021). How digital espionage tools exacerbate authoritarianism across Africa. https://www.brookings.edu/techstream/how-digital-espionage-tools-exacerbate-authoritarianism-across-africa/

Conroy-Krutz, J., & Koné, J. (2022). Promise and peril: In changing media landscape, Africans are concerned about social media but opposed to restricting access https://www.afrobarometer.org/publication/political-participation-africas-youth-turnout-partisanship-and-protest/

Keremoğlu, Eda, and Nils Weidmann (2020) ‘How Dictators Control the Internet: A Review Essay’. Comparative Political Studies. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0010414020912278?icid=int.sj-full-text.citing-articles.1 (Open access)

Lemaire, P. (forthcoming) Online censorship and young people’s use of social media to get news. International Political Science Review.

Resnick, D., & Casale, D. (2011). The political participation of Africa’s youth: Turnout, partisanship, and protest https://afrobarometer.org/publications/political-participation-africa%E2%80%99s-youth-turnout-partisanship-and-protest

Roberts, Margaret E. (2020) ‘Resilience to Online Censorship’. Annual Review of Political Science 23(1): 401–19. https://www.annualreviews.org/doi/10.1146/annurev-polisci-050718-032837 (Open access)

This brief is an output of the project Youth in Africa, on youth representation and job creation in four African countries, funded by the Norglobal programme of the Research Council of Norway. This is a collaborative project including partners from CMI, Institute of Development Studies (UK), Forum for Social Studies (Ethiopia), Institute for Social and Economic Studies (Mozambique), Great Zimbabwe University / Sol Plaatje University (South Africa), Uganda Management Institute, and University of Bergen (Norway).