Artisanal Gold Mining Camps in the Butana (Eastern Sudan) as Migration Hubs

How to cite this publication:

Musa Adam Abdul-Jalil (2023). Artisanal Gold Mining Camps in the Butana (Eastern Sudan) as Migration Hubs. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute (Sudan Brief 2023:1)

Artisanal and small-scale gold mining sites have become large-scale migration hubs for thousands of young men from Sudan and its neighbouring countries. The April 15 war is likely to increase artisanal gold mining since those who were displaced by the war might seek gold mining as a source of income. This could lead to growing pressure on the available services in the camps and intensify competition over resources. Better organization of the mining industry and improved migration management will benefit both the Sudanese and foreign governments, as well as the gold miners themselves.

Main points

- Multiple factors affecting human mobility converge in the artisanal gold mining camps. The camps function as migration hubs for a large number of people who see their stay in the mines as a temporary stop on the way to Europe, the Gulf States or North America.

- Workers get information and logistical support that enables them to plan their journey out of Sudan while living and working in the camps, for example information about possible destinations, routes and reliable traffickers. They also save money to pay for travel expenses.

- Good migration policies are multifaceted. Any successful approach needs to take into account the factors that bring these men to the camps, the conditions they live under while they are there, and the risks they run while travelling towards their ultimate destination.

Sudan’s gold rush

Artisanal gold mining has been a crucial driver in the Sudanese economy ever since the secession of South Sudan in 2011. In less than a decade, the phenomenon has spread very quickly to encompass most of the country. It is now the most common activity among young men seeking to improve their income quickly. Rumours about young men stumbling upon gold deposits and getting rich have spread rapidly, igniting young people’s hopes for achieving their dreams.

Workers now live in more than 200 camps around the country. They are all male, young (between 18 and 35 years of age) and moderately educated. They represent a plethora of backgrounds: From IDPs from conflict zones to poor and unemployed men in search of a better life, and refugees from neighbouring countries. However, for many of the migrant workers, these categories overlap.

Despite the large number of workers in the gold mining camps, we know very little about the dynamics of this labour migration. The lack of information makes it hard to develop policies that address and mitigate the risks the workers run both while in the camps, and on their journeys towards and from the camps. To develop effective policies we need a better understanding of the driving factors and patterns of migration of the workforce in the gold mining sector.

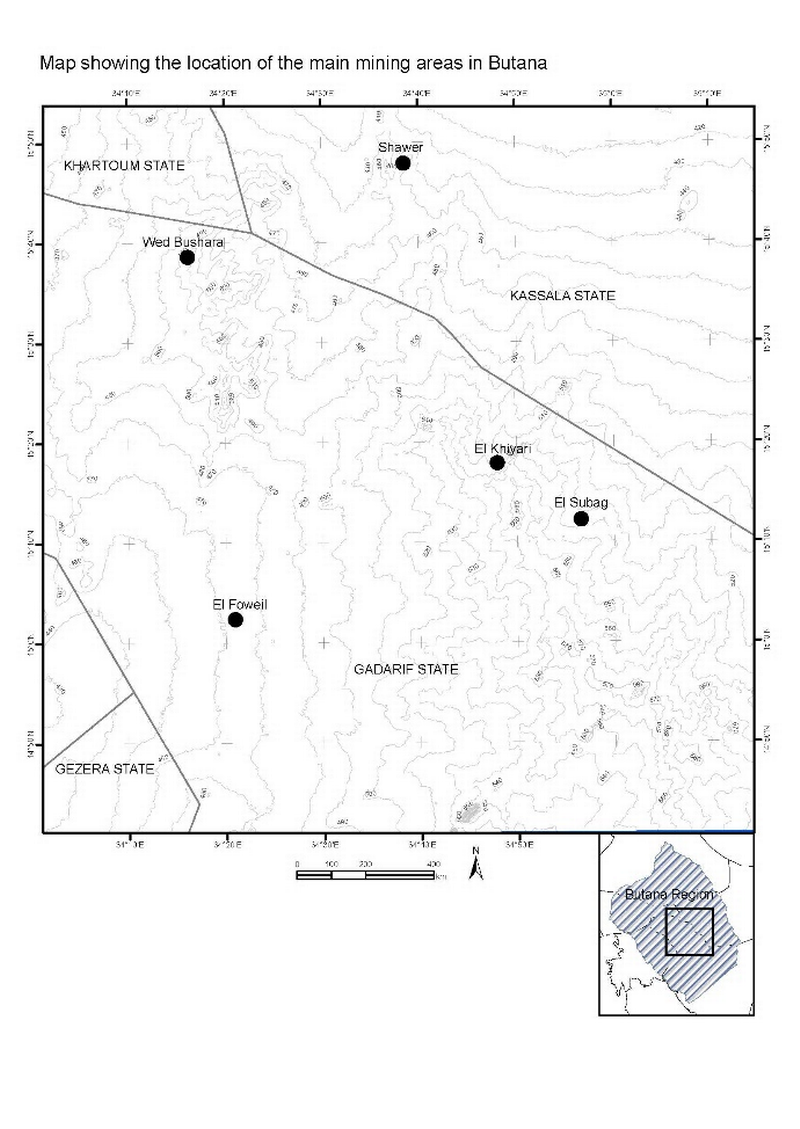

The recommendations in this brief are based on an in-depth study of four gold mining camps in the Butana region: Elkhiyari, Wed Bushara, Shawir, and El Fowell. We also did fieldwork in El Subag, the locality’s administrative headquarters. Fieldwork was conducted twice in January and February 2020.

The United Nations Environment Programme defines artisanal goldmining as ‘gold mining conducted by individual miners or small enterprises with limited capital investment and production’ (UNEP 2014). Artisanal gold mining is labour intensive and uses rudimentary methods to extract and process gold.

Migration hotspots in Eastern Sudan

Eastern Sudan has a long history as a migration route for people coming from Ethiopia, and more recently Eritrea. Sauakin as a port in the Red Sea has also been a point of arrival for people from Yemen who then find their way to the hinterlands.

The Butana plain, a vast area encompassing the five states Gadarif, Kassala, Gazira, Khartoum & River Nile, has long been considered a strategic location for migrants from the Horn of Africa, on route either to Khartoum or directly to Egypt and Libya on their way to Europe. Historically, the Butana represented a sanctuary for animal thieves and, later on, human smugglers and traffickers.

Today, many of the people choosing this route are migrants who take up temporary work in the gold mines. Migrants also come from other areas in Sudan to work in the Butana gold mines looking for a way to make money and to connect with smugglers and human traffickers who can get them out of Sudan and towards Europe, the Gulf countries or North America.

Life in the camps

The majority of the Sudanese workers in the mining camps in Butana come from East Sudan (25 %), Gazira (19%), Darfur (17 %), Blue Nile (13 %), White Nile (11 %), and Kordofan (10 %). Foreign workers come mostly from Ethiopia, Eritrea, Chad, the Central African Republic and South Sudan. As non-Sudanese workers were reluctant to answer questions about their country of origin for security reasons, these results are only indicative.

The new sites for artisanal gold mining have quickly turned into camps that attract thousands of young men seeking work as diggers and processors or in service provision such as water, food, hospitality and transport. The organization of the gold mining camps and the provision of services rest mainly on the mining community itself. Camps are initiated by miners. Government authorities only arrive later when mining in a specific location has become lucrative and revenue collection becomes viable.

The gold production itself is based on a model of fixed shares between three main partners: the owner of the land/well gets 25% and the investor (who provides the working tools) gets 25% while all the workers get the remaining 50%. However, there are brokers who make this happen by bringing the partners together. They receive payment from the investor. It is important to note that only persons who belong to the local tribes can own a well.

The actual mining grounds which are locally called “wells” are scattered in a wide radius. The main camp is where the processing takes place and is usually called “the mills market” which refers to stone crushing and the final processing stages for gold production. The camps have also become vibrant marketplaces for the local population because of the plentiful selection of different types of shops and stores: Groceries, restaurants, butcheries, clothes, barber salons, telephone, accessories and mobile credit shops, and suppliers of digging tools and equipment.

The majority of workers list economic pressures as the most important reason for coming to the gold mine (42%). However, a considerable number list fleeing from war (29%) as the main reason for leaving their home areas. This is particularly the case for those who come from Darfur. Regarding reasons for wanting to travel beyond the borders of Sudan, most of them gave success stories of previous migrants as their main motivation (84%) and 13.3% declared that they have been motivated by the desire to improve living conditions. The two categories could be added together to constitute the economic factor as the main driver of migration. The European Union is the most popular destination for mining workers intending to leave Sudan (69.2%), with Arab countries in the second place (23.1%) followed by Canada (7.7 %).

Telephone communication and social media play an important role in motivating workers to come to the mining camps and later to seek ways to travel outside Sudan. Shops selling telephone accessories and credit are found all over the camps.

The market operates as a meeting place where the local population get the goods and groceries they need, and the gold miners get additional information on travel routes and agents that can help them out of the country.

While in the camps, the migrants mix with the local population in the markets and get access to information about travel routes in addition to establishing connections with smugglers. The Rashaida, a pastoralist tribe that originates from the area between Sudan and Eritrea, have come to play a particularly important role, both in popularizing the gold mining ‘culture’ through facilitating import of metal detectors and as an active part in the informal cross-border trade including human smuggling and trafficking taking place between Eritrea, Saudi-Arabia, Yemen and Sudan. Like the Rashaida, the majority of smugglers come from the local area, drawing upon their extensive knowledge and understanding of the routes leading through the desert.

The smugglers and trafficking operators have agents in the camps who actively look for possible clients. As such, the gold mining camps are in practice effective migration hubs where the marketplaces are not only markets for trading and buying goods, but also play additional roles of harbouring migrants and providing them with logistical support to continue their long and arduous journey to their final destination.

Primary data was gathered mainly through quasi-participant observation, in-depth interviews and focused-group discussions. We also distributed a questionnaire among mining workers using a snowball sampling method which produced quantitative data. Secondary data was obtained from administrative and security offices on-site as well as from relevant government departments at state and locality headquarters.

Conclusion

As a recently invigorated economic and social phenomenon artisanal gold mining seems to represent an arena where multiple factors pertaining to human mobility converge. People in economic need/poverty, IDPs and refugees move to gold mining centers seeking to alleviate their dire conditions. The gold mining camps function as migration hubs for many who intend to migrate to other countries. Europe, Arab Gulf countries, and Canada are the favoured destinations.

- Potential migrants get information and logistical support from these camps that enable them to plan their journeys outside Sudan.

- In any one migration flow, several driver complexes may interconnect to shape the eventual direction and nature of movement. The challenge is to establish when and why some drivers are more important than others, which combinations are more potent than others, and which are more susceptible to change through external intervention.

- To understand migration flows better, analysts could usefully distinguish between predisposing, proximate, precipitating and mediating drivers. Combinations of such drivers shape the conditions, circumstances and environment within which people choose to move or stay put, or have that decision thrust upon them.

Policy recommendations

- Artisanal gold mining is driven mainly by young men spontaneously responding to news of prospectus sites. Government officials merely follow newly established sites to start revenue collection. The industry needs concerted efforts to organize it. Having clear policies especially regarding employment, safety and training of the workforce is of crucial importance not only to the national government and mining workers, but also to the countries that are on the receiving end of the migrant flow.

- Sudan lacks a comprehensive and coherent migration policy; hence it is difficult to get accurate information on population mobility. This makes it difficult to understand the exact drivers for internal and external migration. In this connection, it is important to recognize that criteria like poverty, IDP and refugee are not mutually exclusive. Registration of arrivals at the camp sites is a starting point.

- There is a complete lack of statistical information regarding the population present in the mining camps. New arrivals are not registered and the same applies to those leaving the camp. Likewise, there is no systematic data registry from which the characteristics of the population of the camp may be derived. A data bank for gold mining workers is needed to understand the characteristics of those involved in the industry and their mobility cycle. Transport stations may be the best place to start from. Registration should be voluntary but could be linked to incentives like free access to health clinics.

- Foreign labour also needs to be organized through licensing and registration. Such measures can help secure their human rights as well as enabling the government to control criminal and illegal activities.

About this brief

This brief is an output from the Assisting Regional Universities in Sudan (ARUS) and Sudan-Norway Academic cooperation (SNAC). Both programmes are funded by the Norwegian Embassy in Khartoum. The author would like to thank Ibrahim Ali Abakar, Yahya Haroun Salih and Ad Abdallah Onour Hasan from the University of Gadarif who contributed substantially in data collection and analysis.