The women’s rights champion. Tunisia’s potential for furthering women’s rights.

Tunisia as case study for women friendly law reform?

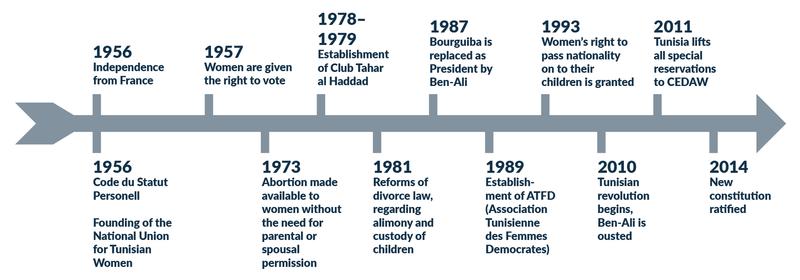

A brief history of the women’s movement in Tunisia

History of women’s status in Tunisia

2015: Transition, Islam, and the current Tunisian identity crisis

How to cite this publication:

Mari Norbakk (2016). The women’s rights champion. Tunisia’s potential for furthering women’s rights.. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI Report R 2016:5)

Introduction

Tunisia is a country in the midst of its post-revolutionary transition, and the status and legal position of women since the 2011 “Jasmine Revolution” is central to this transition. This report addresses the prospects for women-friendly family law reform in Tunisia in the aftermath of the 2011 evolution, with a particular focus on the potential impact of the 2014 Tunisian constitution. {1}

The process leading to the promulgation of a new constitution has been covered widely in media and academic scholarship, but implementation of the constitution has not yet been completed. Although implementing the constitution will require law reform, this has yet to come to pass, in part because Tunisia does not yet have an operative constitutional court, as stipulated by the new constitution (arts. 118–124). This leads to a number of conflicts between the highest law of the land and the domestic law that currently often prevails.

In the area of women’s rights, the constitution sets forth a principle of equality that is a departure from the currently applicable family law – the Code du Statut Personnel of 1956 (CSP){2}. A particularly stark example is the case of inheritance law: under the CSP women are only due to inherit one-half the share due to a man, but article 21 of the new constitution states, “All citizens, male and female, have equal rights and duties, and are equal before the law without any discrimination.” Although Tunisia lifted all special reservations to the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) after the revolution, it has yet to revise domestic laws to conform to the principle of equality for all citizens that is mandated by the new constitution.{3}

Another central issue in implementing the constitution is the ambiguous nature of the constitutional text itself, which specifies that international treaties are superior to domestic law, but does not specify what weight should be given to sharia law vis-à-vis international treaties. The yet-to-be-established constitutional court will have to settle this ambiguity as well as conflicts between the constitution itself and currently applicable family law. During interviews conducted as part of the fieldwork for this report, activists, politicians, and legal professionals mentioned how Tunisia is facing an “identity crisis.” This report considers this perspective and attempts to make sense of the constitution’s ambiguities. As such, this report does not conclude how the constitutional implementation process will play out, but does shed light on the on-going process and how legal professionals, politicians and activists in Tunisia view the possibilities for change.

The report also analyses the history of women’s status in Tunisia. Although Tunisia is often viewed as a secular country, Islam plays an important role both as the basis of the country’s national identity and also as the source of legal thought and the legal framework. In fact, some people interviewed in preparation of this report consider the Tunisian school of Islamic thought to be central to the liberal gender project in Tunisia. The legacy of former president Habib Bourguiba is central to the development of a post-independence state in which women have revolutionary rights (such as the right to vote, to obtain free abortions, to avoid polygamy, and to divorce.).

{1} Constitution of the Republic of Tunisia of 2014, translated and printed by the Jasmine Foundation – Tunisia [hereinafter 2014 Const.], http://www.jasmine-foundation.org/doc/unofficial_english_translation_of_tunisian_constitution_final_ed.pdf. The term “family law” specifically refers to the Tunisian personal status law, in particular, the Code du Statut Personnel of 1956.

{2} http://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/natlex4.detail?p_lang=en&p_isn=73374

{3} Tunisia’s remaining reservation to CEDAW are outlined in the official document to withdraw: https://treaties.un.org/doc/Publication/CN/2014/CN.220.2014-Eng.pdf

Key findings

Tunisia’s 2014 constitution guarantees gender equality (see art. 21), but implementation is slow and discriminatory laws continue to exist at lower levels of government. The constitution does not set forth ground-breaking new rights for Tunisian women, but it does it guarantee (at least in word) their already celebrated status. Importantly, the constitution also gives international treaties priority over domestic law (art. 20). This means that if Tunisia were to lift its remaining reservations to CEDAW, this could help the country further address sensitive women’s issues (such as inheritance and citizenship rights) through court rulings. Of course, this would depend on judges’ knowledge about these international standards and their will to apply them.

At the same time, however, the constitution is ambiguous about the role sharia is to play in relation to other legal authorities. This means that courts of law – including the constitutional court – will play a key role in resolving disagreements and ultimately determining how the constitution is implemented.

Finally, in spite of the constitution’s progressive language, women still face legal discrimination in a number of key areas, including their ability (i) to inherit, (ii) to obtain citizenship rights for a foreign spouse, (iii) to obtain custody of their children in the case of remarriage after divorce, and (iv) to receive protection in situations of domestic violence. Women who work in the private sector also face challenges because of uneven implementation of labour laws.

Fieldwork and method

Fieldwork for this report was carried out in Tunis in April and May 2015. Meriam Fatnassi coordinated the interviews and acted as interpreter for interviews not conducted in English. Most interviews were conducted with politicians, activists, legal professionals and development professionals in their professional capacity, and full names are therefore reported here. However, a couple interviews were conducted under condition of full anonymity, and those interviewees’ names have been withheld in this report.

In addition to interviews, the anthropological method of participant observation was also employed to gain more informal information. The data collected in this manner are secondary to this report and were primarily intended to inform the author’s understanding and interpretation of the interview material.

Notably, members of Tunisia’s Salafi movement{4} were not available for interviews during one month of fieldwork in Tunis. In part, this was because Ms. Fatnassi’s network consisted primarily of religious liberals and members of “legitimate” political parties. In addition, both interlocutors and other network contacts showed a great deal of scepticism whenever they were asked for help getting in touch with members of the Salafi movement. Based on interviews with liberals and Ennahda Movement{5} members in preparation for this report, it is clear that the Salafi movement is considered something foreign (Gulf-inspired) that is linked to attacks on the tourism industry and the Islamic State.

It also proved difficult to get interviews with members of the “big” women’s rights organisations, the Tunisian Association of Women Democrats (ATFD) and the Tunisian Women’s Association for Research and Development (AFTURD). During an interview with a former ATFD member, we learned this was because these organisations are currently undergoing restructuring and fear infiltration. These groups are therefore dealt with through rich secondary sources.

The interviews were all organised after the author’s arrival in Tunis. During interviews, snowballing strategies were employed to gain further contacts from interviewees, who would suggest others who should be interviewed. The researcher (accompanied by the coordinator) gained entrance to a number of gender trainings and conferences, and discussions at those events led to additional appointments. The fieldwork also included a visit to parliament, with interviews conducted in the wings between sessions. Several individuals offered to do interviews at their offices, which provided occasion to visit several party headquarters. However, the interviews conducted in more informal settings, such as at a café or in a person’s home, tended to yield more candid statements, although individuals interviewed in such settings were also more likely to request anonymity.

{4} Salafism is a fundamentalist movement within Sunni Islam, seeking (in different ways, both political and a-political) to recreate themselves and the Islamic community in the image of the “righteous forefathers” (El salf el salih). They seek to return to the sources, and the ways of life of that time, and are considered very conservative. Some Salafis believe Islam is apolitical while others have a political project, like the Salafist movement referred to here.

{5} The Ennahda Movement, also known as the Renaissance Party, has been a moderate, Islamist political party in Tunisia since 1981. It has oscillated between being a legitimate political party, and being outlawed, depending on the general political and religious climate.

Tunisia as case study for women friendly law reform?

Social sciences literature has already deeply explored the legal status of women in Tunisia, and the country has been hailed as a forerunner for women’s rights in Muslim countries (see Charrad 2007, 2012; Charrad and Zarrugh 2014; Labidi 2007; Moghaddam 2005; Voorhoeve 2012). Tunisia is often viewed as different – even marginal – from other Middle East and North Africa (MENA) states. The country is famous for historically promoting women’s rights in the country’s legal and state structure, as well as in social settings. Scholarship on the topic tends to focus on the apparent opposition between being a Muslim state and maintaining women’s legal rights (particularly in the realm of family and private life). There seems to be some fascination with how Habib Bourguiba’s dictatorship not only gave legal rights to women, but also provided for their maintenance through social institutions (see Charrad 1997 and 2007 for further analysis).

After the 2011 revolution in Tunisia, the status of women made headlines all over the world, as the 2012 draft constitution proposed an article stating that men and women are “complementary” in the family, as opposed to equal partners (see art. 2.28, the “complementarity clause”).{6} This led to a massive media campaign and large demonstrations, and in the end the article was dropped. The outrage related to this proposed constitutional provision – as well as the heed given to this outrage by constitutional drafters – cemented Tunisia’s reputation as a leader on women’s rights. However, it also exposed an underlying identity crisis regarding the role Islam should hold in the new Tunisian state. This identity crisis was discussed during a number of interviews conducted in preparation for this report.

What makes Tunisia such an interesting case compared to other Muslim countries is that the women-friendly laws are not considered to be in opposition to Islam (see Mashour 2005; Charrad 2007). Rather, they are considered an intrinsic part of Tunisia’s brand of Islamic philosophy and fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence), as related to the author during fieldwork (see also Largueche 2010). Although Tunisia is often considered a secular country, Islamic sources have been central to the construction of family law there (see, e.g., Charrad 2007). As discussed further below, the legal reforms the post-independence Habib Bourguiba administration instigated were branded as “a new phase in Islamic innovation,” rather than as a departure from Islam (Charrad 2007, 1519). For example, inheritance laws in the CSP are clearly influenced by (and in part copied from) sharia sources. One CSP chapter dealing with inheritance discusses “Quranic inheritance” – wording lifted directly from the Quran (An-Nisa’, 4: 11).{7}

Women may use a reformist view as a tool of empowerment to argue that sharia is not in conflict with human rights and gender equality, but there also seems to be a tendency to equate Tunisia’s friendliness to women to an understanding of secularism (Charrad 2007; Wing and Kassim, 2007; Grey 2012){8}. Nonetheless, even the more “secular” women interviewed for this report related in some way to an Islamic frame. The explanation for women’s status in Tunisia today is related in part to the history of Islamic thought in the country, including a Tunisian “brand” of Maliki fiqh. Although Bourguiba is regarded as the CSP’s initiator, and the CSP is viewed as a secular legal framework, it is clear that it has characteristic roots in Maliki fiqh (see Charrad 1997).

{6} Draft Constitution of the Republic of Tunisia of 2012, http://www.constitutionnet.org/files/2012.08.14_-_draft_constitution_english.pdf.

{7} However, this chapter outlines one of the lingering inequalities in Tunisian family law, the unequal treatment of women and men in their shares of inheritance.

{8} Note that the authors cited here speak of Tunisia as “more secular” than other Muslim countries, but they do not dismiss arguments made by the Bourguiba administration that the administration’s legal reforms were part of ijtihad (decision-making through independent reasoning). As such, they were Islamic.

A brief history of the women’s movement in Tunisia

Zine El Abidine Ben Ali was president of Tunisia from 1987 until he fell from power in 2011. With him, the “the old order” also supposedly fell, and a new era of political mobilisation flourished (see Khosrokhavar 2012, cited in Charrad and Zarrugh 2014, 232). As my young coordinator and interpreter told me, through participation in the protest movements, Tunisian youth learned about democracy and political process. The learning process was quick, and the country saw political parties pop up and register at a high rate, along with a plethora of civil society organisations and popular movements (see ibid.). This was also true for the women’s movement, which had operated in Tunisia for decades before the revolution.

Women’s rights efforts before 2011: A partner of the regime

Prior to the 2010–2011 uprising, the women’s movement was defined by close collaboration with the regime, working alongside (rather than in opposition to) the administration. In doing so, the movement made important contributions to, and contributed to a regime guaranteeing Tunisia’s status as “best in class” when it came to women’s rights and gender equality. Indeed, the movement even furthered women’s rights, as evidenced by reforms to divorce and citizenship rights in the late 1980s and early 1990s. However, an independent women’s movement only arose in Tunisia after the revolution.

Ben Ali created the Secretariat of State for Women and Family in 1992, and it became the Ministry of Women’s Affairs, the Family and Children, and the Elderly (MAFFEPA) in 1992. Its mandate has been to “co-ordinate and develop government policy for women’s promotion” (Chambers and Cummings 2014, 25). The ministry had local branches in all of Tunisia’s seven districts until at least 2010. These branches aimed to “reinforce women’s participation in public, political and socio-economic life at the sub-national level” (ibid.).

Table 1 below describes the central women’s rights organisations prior to the revolution, as compiled by researchers at the Overseas Development Institution (ibid.). Many of these organisations remain a definitive force to be reckoned with. In particular, AFTURD and ATFD continue to be two of the most prominent women’s rights organisations in Tunisia – along with the newly formed Egalité et Parité.

Table 1. Key Tunisian women’s organisations (Chambers and Cummings 2014, 25)

|

Date of formation |

Name |

Description |

|

1956 |

National Union for Tunisian Women (UNFT) |

The UNFT was the only voice for women in the immediate post-independence era and is represented in all regions and in the remotest parts of the country.* It has formed alliances with professional/special-interest women’s groups and operates in a framework of partnerships with governmental structures or national organisations (i.e. in tackling illiteracy). It was the exclusive channel through which women could be elected to the RCD [Ben Ali’s party] lists in local and national elections and many women who have reached decision-making positions (particularly political) have been UNFT members (Gribaa et al., 2009: 102). |

|

1978/1979 |

Club Tahar El Haddad** d’études de la condition de la femme (CECF) |

Started by elite educated women (executives, teachers, journalists, lawyers, students), the club addressed women’s dissatisfaction with women’s limited advances in political participation and prompted demands for further rights. |

|

1983 |

Union of Tunisian Workers ‘women’s commission’ (UGTT) |

Created at a round table organized by CECF.

|

|

1985 |

The Nissa Group

|

Created a bi-monthly journal to address women’s issues. Its various objectives included the defence of the CPS, encouraging women’s political participation, and highlighting the role of women’s hidden work. It published eight issues between 1985 and 1987. |

|

1985 |

Tunisian League for Human rights (LTDH)

|

A women’s commission of the LTDH was created in 1985. |

|

1989 |

Tunisian Women’s Association for Research and Development (AFTURD) |

Created following political liberalisation in 1987, AFTURD was a response to demands from the various women’s organisations and was made up of women academics. It was set up to carry out research on how to integrate women in economic and social development and has a broader societal agenda with a focus on women’s conditions. |

|

1989 |

Tunisian Association of Women Democrats (ATFD) |

Created following the Copenhagen convention by Arab-Muslim women, the ATFFD takes political, social and cultural action to defend, consolidate and develop women’s rights in the face of attempts to curtail them. |

* The UNFT has extensive grassroots membership and up to 2010 had 27 regional delegations and 650 local sections.

** Ms. Bourguiba is the former president’s granddaughter, and splits her time between Tunis and London.

The women’s movement after 2011: Old and new forces at work

Following the 2011 revolution, ATFD and AFTURD are still considered “heavyweights” among the NGOs that advocate for women’s rights, but are currently viewed as undergoing restructuring and reorganization to fit into the new political context. For example, ATFD organised and spearheaded a 2012 demonstration to protest the complementarity clause of the draft constitution (Antonakis-Nashif 2016). AFTRUD is a research organisation that prepares papers and reports for use by legal practitioners and activists. In fact, one of the lawyers interviewed for this report referenced and displayed AFTURD reports in her office, as tools she regularly employs.

ATFD and AFTURD are by some newer gender organisations considered to be old-fashioned, elitist (Antonakis-Nashif 2016), and in some ways tied to Ben Ali’s regime. This also came up in informal conversations I had with young politicians. In particular, Ben Ali’s regime tolerated ATFD (although they were kept in check, and members were kept under surveillance, (ibid.)), which has led to criticism of the group today. Both groups are (supposedly) currently undergoing restructuring and redefinition, as they have lost members to newer organisations, such as Egalité Parité. Several of the new political parties, such as Afek Tounes, also have some sort of gender/women’s sub-group. No interviews were conducted with members of the “old-timer” (ATFD and AFTURD) organisations. One former ATFD member, Iman Noura Azouzi, explained that the group is sceptical towards outsiders due to fear of infiltration and its reputation as an instrument of the former regime (interview 30 Apr. 2015).

Egalité Parité (“Equity and Equality”) is a new player in the NGO sector. This organisation came into being during the revolution and works to implement equality and parity (interview with Azouzi, supra). Some founding members were formerly part of other organisations such as ATFD but left after the revolution created more space for civil society organisations.

In addition, a the national labour organisation UGTT (Union Générale Tunisienne du Travail) has served the women’s rights cause in the past (e.g., during reforms in the 1990s) and continue to do so today. In addition, most political parties have a “women’s affairs council” or similar body.

Tunisia’s primary state-level women’s rights institution continues to be MAFFEPA (Chambers and Cummings 2014, 25). MAFFEPA is currently led by a woman, Naziha Laabidi, and, in fact, has often been the only ministry to be headed by a woman (Ben Salem 2010). The ministry is responsible for, amongst other things, to formulate action plans for the furthering of women’s rights, but as was relayed to me informally in Tunis, the ministry, as it is also tasked with responsibility also for youth and the elderly, efforts and resources may be spread thin.

Finally, a plethora of other organisations – small and large, domestic and international, independent NGOs and political think tanks – also operate in Tunisia. During fieldwork, I observed a dynamic and active community of political actors committed to women’s issues. It appears that international political actors, such as party-affiliated think tanks, as well as domestic actors are part of a training industry that regularly offers workshops, seminars, and other types of “gender training.” Often these trainings are targeted towards politicians and local NGOs. International youth; interns, activists, who are funded by their home organisations (both political parties and think tanks) are often involved in organizing the trainings and workshops.

These many bodies have become a formidable force promoting women’s rights in Tunisia. For example, in 2012, many members of the women’s movement joined forces to protest the complementarity clause in article 2.28 of the draft constitution, demonstrating that some of these groups have the ability to work together. At the same time, however, Tunisia’s political landscape has been blown wide open since the revolution (Charrad and Zarrugh 2013; Goulding 2011; Chambers and Cummings 2014). The field is now full of actors dedicated to women’s rights, and they have become fractionalised by an abundance of political ideologies, as well as by a growing field of “gender professionals.” This dynamic environment of dedicated advocates is a sign of health, but it does lead to a lack of coherence, especially given a lack of unifying, “sexy” issues. For example, as regards the issue of implementing the constitution, these groups have widely varying arguments as to which issues are most pressing. Nevertheless, Mériem Bourguiba, one of the central figures in the post-revolutionary women’s rights movement, maintains that civil society is playing and will continue to play a central role – both as actor and as watchdog – even in spite of the current lack of unifying causes (interview 23 April 2015). Furthermore, legal practitioners do not appear to be worried about the current lack of cohesiveness among women’s rights groups; during interviews they expressed that they see the tools at hand (constitution, international treaties, and Tunisia’s domestic laws) as sufficient to ensure women’s rights.

History of women’s status in Tunisia

Much of the honour for the position of Tunisian women in legal and social matters is attributable to former president Habib Bourguiba, who led the country after its independence from France in 1956 until his removal from office in 1987. Unlike the leaders of other post-colonial MENA states, Bourguiba focused on establishing and funding comprehensive educational initiatives and a welfare system, rather than on building a strong military and involving it in politics (Barany 2011; Perkins 2014). While this laid the groundwork for Tunisia’s progressiveness in issues such as women’s rights, Tunisia’s failure to build a strong military force haunts the Tunisian populace today, as the unpopular army attempts to safeguard Tunisia against external and (perhaps even more pressing) internal threats against national security (Barany 2011).

Through an authoritarian “top-down” approach, Bourguiba introduced the still-famous Code du Statut Personnel. The CSP primarily concerns personal status and, among other things, deals with men and women’s respective rights and duties within the family. Bourguiba’s administration also implemented a welfare state designed to educate and ensure the basic health of Tunisia’s population – including through radical family planning initiatives, such as free contraception and abortions (Hessini 2007).

Mounira Charrad (2007) argues that Bourguiba’s goal was not merely his citizens’ well being, but also was breaking down tribal alliances and centring the Tunisian populace’s loyalty on the state. She also argues that Bourguiba was eager to see the new state loyal to secular values. Thus, although he did not completely break with the ulema (Islamic scholars, the recognized authorities on Islamic knowledge), he constructed a state that would provide welfare services to the population, so that it would not need the type of welfare traditionally offered by Islamic institutions{9}. One could therefore argue that through Bourguiba’s construction of an authoritarian state he also laid the foundation for the position women hold in Tunisia today.

Charrad (2012) outlines two periods of reform that were significant for the status of women in Tunisia prior to the 2011 revolution.{10} The first period – in the 1950s – culminated in Bourguiba’s creation of the CSP in 1956. Among other things, this radical code (i) granted women an equal right to instigate divorce as their husbands, (ii) set a minimum age for marriage, and (iii) required both parties to consent to a contract marriage (arts. 5, 9). The code also abolished polygamy (art. 18) and granted women the full right to work, move, open a bank account, and start a business – all without the permission of their husbands (see Charrad 2012, 4–5). At the same time, however, Bourguiba’s authoritarian regime curtailed the feminist movement, since only the state-sanctioned National Union of Tunisian Women (UNFT) – formerly the women’s affairs committee of Bourguiba’s own party – was allowed to operate (Goulding 2011). Bourguiba’s rule also saw women given the vote in 1957, very early in a worldwide context (Murphy 2003, 173). The second period consisted of reforms under Ben Ali in the early 1990s, which granted women the right to pass citizenship to their children, to receive alimony in cases of divorce, and to obtain custody of children upon the death of their husband (Charrad 2007; 2012, 6). Both of these waves of reform have underpinned Tunisia’s fame as a champion for women’s rights in the region. It is clear from interviews with Tunisian women and men that this role is a source of pride (also noted in ibid., 1527, where Charrad argues that Bourguiba’s top-down reforms created a “powerful rallying cause”). The status of women in Tunisia is considered a national symbol even among the more religiously and political conservative individuals who were interviewed for this report.

Charrad (2007) links these two waves of reform to the different political powers at work. She asserts that the first wave of the 1950s was linked to a top-down authoritarian system concerned with establishing a new nation-state and moving power away from patriarchal, kin-based organisations (ibid. 1997, 295–296; 2012). The second wave of reform was due in large part to the influence of women’s rights advocates that arose following independence and put both direct and indirect pressure on the regime (ibid. 2012, 5). Like Charrad and Zarrugh (2014), one could argue that this tendency towards a process influenced by civil society continued at least through the Tunisian revolution of 2011, and likely even into the transition phase. A vivid example of the way women’s rights advocates have influenced legal processes was the massive demonstration on 13 August 2012 to protest the complementarity clause of the draft constitution (interview with Bourguiba, supra; see also Charrad and Zarrugh 2014).

In short, even though the women’s rights laws and other social reforms in Tunisia were instigated and forcefully implemented top down, Tunisian women of multiple political backgrounds are proud of their country’s status as a women’s rights champion.{11} In an interview with the head of the Tunisian Union of Judges (le Syndicat des magistrats tunisiens, SMT) Ms. Raoudha Abidi said with a smile, “We have no Khul divorce here{12}” (interview 4 May 2015).

Zine El Abidine Ben Ali overthrew Habib Bourguiba in 1987 as part of a bloodless coup. Legal reforms and a liberal stance supporting women’s rights continued under Ben Ali, but so did the limited freedoms of the feminist movement. Although Ben Ali’s regime allowed for more organisations to operate freely, feminism was still a state-sponsored and controlled issue. The “independent” organisations were supposed to support, not challenge, the government, and they had to be approved by the Ministry of Culture (Shraeder and Radissi 2011; Cavatorta and Haugbølle 2012). Under Ben Ali, women gained more rights, including an expanded right to transfer their citizenship to their children in the case of marriage to a non-citizen, the right to alimony in the case of divorce, and the right to custody of the children in the case of the husband’s death. In Ben Ali’s early days, he also allowed for reforms in labour laws that guaranteed women equal pay and removed the requirement that a woman must get her husband’s permission to work (Ben Salem 2010, 14). Interestingly, under the 1956 CSP, a woman is not obliged to obey her husband, but has a duty to contribute towards the maintenance of the family, should she have the means to do so (interview with Mounir Argoubi, 2 May 2015; see also Ben Salem 2010; CSP art. 23).

Nonetheless, society suffered as a whole under Ben Ali, primarily because – according to interviewees – Ben Ali did not provide sufficient financing of the comprehensive welfare system, particularly the health clinics and schools. Several interviewees explained that as a consequence Tunisians’ physical well-being and educational level suffered. This mismanagement negatively affected women’s progress during Ben Ali’s regime and led to complaints that Ben Ali and his cronies were lining their pockets as the Tunisian public suffered (Shraeder and Redissi 2011, 9; Cavatorta and Haugbølle 2012, 185). This in part fuelled the 2010–2011 uprising.

It is clear from the literature available that the active involvement of women and an organised women’s movement in politics has increased throughout the history of independent Tunisia – from the top-down, authoritarian approach of the Bourguiba administration to the active leadership at both central and grassroots levels that influences Tunisia today (e.g., Tjomsland 1992; Charrad 1997; 2007). UNTF and CECF spearheaded legal reforms in the late 80s and early 90s, showing that woman actively participated in the state-sanctioned women’s movement (Charrad 1997). This contrasts with Bourguiba’s earlier promulgation and implementation of the 1956 CSP, which came from the administration as part of the nation-building project.

The development of a progressively more active women’s movement can be seen as parallel to the process of gradual democratisation of national politics in Tunisia. As outlined in Tjomsland (1992), throughout the 1980s, party politics in Tunisia diversified as more parties became allowed. However, it was only post-revolution that the Ennahda Movement (a moderate Islamist movement) was sanctioned to participate in national decision-making. Since 2011, the party has played a central role in the process of transition and constitution making.

Abortion

In 1973 Bourguiba’s administration legalized and ensured women’s access to free abortions, completely at the woman’s choice. Abortions were permitted before 1973, but at this point they became available to women without a need to inform their spouse. When asked about abortion, both men and women, also from conservative politico-religious backgrounds say abortion is allowed by Islam. The concept of ensoulment is central here, and according to Hanafi fiqh, the ensoulment happens at 12 weeks, which means abortions up to this date is not in conflict with Islam (Eich, 2009). (But: Maliki fiqh tends to be restrictive here – so there seems to be an eclectic use of different sources here) None of the interviewees thought abortion was a radical issue in Tunisia, although a young man, Muhammad Khalil Baroumi , radio journalist and Ennahda member thought that although women have the right to have abortions without the knowledge of their husbands, “she should discuss it with me”.

As I visited some middle-aged and elderly women informally, they eagerly waited for me to finish my meal before they bluntly asked me if abortions were allowed in my country. I answered that it was, and like in Tunisia also paid for by the state. They went on to tell me openly about their own abortions, chuckling about how one of the women had her 6-year-old son take her to the clinic, as she did not feel the need to inform her husband, and she was told she had to have someone bring her home after the procedure. It was quite clear that abortion is not a taboo-issue, nor is it an issue which is contested in public discourse.

The 2011 Tunisian revolution:

Women’s role as revolutionaries and freedom fighters

Women played an important role in the Tunisian revolution of 2011. They took part in the protests, both as participants and as leaders (Tchaïcha and Arfaoui 2012; Charrad and Zarrugh 2013; 2014; Khalil 2014). The revolution and the transition process that has followed have encompassed a variety of actors with differing perspectives and views on the role of Islam in the state; nonetheless, in spite of differing perspectives on the issue, Islam and moderate Islamist views and politics have become part of the human rights – and women’s rights – discourse in the country post-revolution.

In particular, religious freedom has been one of the fundamental rights sought through overthrow of Ben Ali’s dictatorship. Women’s right to veil for instance, has become entangled with the human rights discourse, and has been seen as a symbol of the suppression of religious rights exercised by Ben Ali’s regime.{13} Female Ennahda members interviewed for this report underscored how the veil was banned in the 1980s and how they felt the need either to avoid public spaces and certain career paths under the deposed regime or to unveil in order to develop professionally (interviews with Ms. Farida Labidi, 5 May 2015; Ms. Kalthoum Badreddine, 5 May 2015).{14} A woman’s freedom and equality must include the freedom to choose her attire, her religious orientation, and her political affiliation. Thus, the women of Ennahda who chose to veil under these circumstances also view themselves as freedom fighters, revolutionaries, and “modern” women.

After the revolution, a constituent assembly was formed and tasked with drafting the new constitution. This process was at times quite rocky, and at one point in 2012 the whole process broke down, which created the need for the now Nobel Peace Prize-winning National Dialogue Quartet to step in and mediate the process. One of the issues contested prior to the collapse was a draft provision (art. 2.28), which stated that men and women have “complementary” roles in the family.{15} This article launched massive protests, as well as an international media campaign. In this debate it became clear how women’s status are entangled with the larger debate on Islam’s position in post-revolutionary Tunisia.

The Ennahda movement was the most important provider of women representatives to the constituent assembly (Charrad and Zarrugh 2013), as the largest party involved. As Charrad and Zarrugh argue, Tunisian women’s activism cannot be viewed in a “religion/secular binary” (ibid.). Rather, the experience of Islamist women involved in Tunisian politics reflects how Islam provides “a source of their political engagement and subjectivity” (ibid.). In other words, Islam – and Islamism – is a frame in which some women put forth their political views and push for reform. This also suggests that women were likely involved in supporting the complementarity clause in the draft constitution – and may have even argued that their empowerment was complementary. In an interview undertaken in preparation for this report, Ms. Farida Labidi said that the clause was misunderstood. I return to this issue below.

Post-revolutionary transition

Since the revolution, Tunisia has embarked on a process of democratic transition. This process has not been smooth sailing, but has nonetheless moved forward in some aspects. For example, a minister of human rights and transitional justice has been appointed, and the establishment of a constitutional court is underway (albeit more slowly than outlined in the constitution). At the same time, however, actual implementation of the new constitution, and following through the process towards legal reform (which the Constitutional Court will be tasked with) seems more elusive. The different practitioners, activists, and politicians interviewed in preparation for this study indicated that it is not yet clear how the process of legal reform will be handled, who will handle it, and to whom that body will be accountable. Ms. Rym Mahjoub Massmodi, a former member of the constituent assembly and current member of parliament (MP for Afek Tounes{16}), highlighted during an interview that the constitution was intentionally left ambiguous in certain matters, so that it would be acceptable to a plenary body that consisted of competing political and religious fractions (interview 25 Apr. 2015).{17} This therefore gives more definition-power to the Constitutional Court, as legal ambiguities will have to be settled there.

Ms. Mahjoub Massmodi explained that different committees wrote different parts of the constitution, and the process was not always transparent. During her interview, she claimed that draft article 2.28 (regarding complementarity in the family) was drafted by a committee and came back to the constituent assembly looking nothing like the provision the assembly had previously discussed. Disagreements and public outrage surrounding this draft article were part of the reason for the subsequent collapse in the negotiations (along with disagreement about the form of the state and Islam’s role in the state, as well as two political assassinations). The demonstration staged by different women’s rights organisations on 13 August 2012 (Charrad and Zarrugh 2013; 2014) were part of this process of upheaval – which led to the National Dialogue Quartet’s negotiations.

Ennahda has been accused of inserting the offending article into the draft constitution, but during interviews with MPs from Ennahda it was never clear who was responsible for its creation. Nonetheless, as Ms. Farida Labidi vehemently maintained in a short interview, the complementarity clause never meant “non-equality.” Ms. Labidi sat in the constituent assembly as part of the Ennahda delegation and has been quoted in international media regarding the complementarity clause. Both she and her fellow party member Kalthoum Badreddine have argued that the complementarity clause was meant to highlight how men and women have different – but equal – duties in the family (but was, according to Badreddine, supposed to have no bearing on the relationship between men and women in other arenas, such as in the labour force). They have maintained that the intention behind the complementarity clause was misunderstood and became a political symbol (also see Charrad and Zarrugh 2014).

Gender complementarity

The idea of complementarity of the genders is not necessarily purely religious (or only Islamic); it reflects the ideas that gender is an essential characteristic of an individual and that natural differences between the sexes makes for different abilities, desires, and societal roles. According to Tjomsland (1992, 20–21), the notion that the genders are complementary in rights, duties, and abilities is based on the legal conception of the family as the basic unit in society (as opposed to the individual person). This opens up a view of members of a family as bounded, and reliant upon each other (see also Joseph 1993; 1994). Inside a family, the genders therefore complement each other in order to fulfil the family’s duties in its social contract with the state. However, the debates surrounding the complementarity clause of the proposed Tunisian constitution exposed religious fault lines. It may appear that in Tunisia political conservatism towards family and gender matters is associated with Islam, and Ennahda.{18}

The main argument against the complementarity clause was that by providing different rights and duties to men and women, the draft provision would be the start of a slippery slope into gender discrimination and segregation. However, article 7 of Tunisia’s 2014 constitution states, “The family is the basic unit of society and the State shall protect it.” In other words, the “victory” for the women’s movement in 2012 in managing to stop the complementarity clause from becoming part of the final constitution was not a step forward; rather, it merely safeguarded existing rights, since the 1956 constitution also guaranteed “equality for all citizens.” The only real extension of women’s rights in the 2014 constitution is the inclusion of article 46, which states that it is the state’s responsibility to protect and further women’s equal opportunities as well as to work towards ensuring parity.

{9} Charrad (2007) underlines that Bourguiba’s regime continued to rely on basic Islamic tenets. In fact, during promulgation of the CPS, the administration maintained that the new law was not a break with Islam, but rather was “a new phase in Islamic innovation, similar to earlier phases in the history of Islamic thought” (ibid., 1519).

{10} There have been other stages of women’s rights reform, but these two periods led to substantial change in laws relating to women’s status and are therefore considered the most central periods in time.

{11} In addition, by those from moderate Islamist backgrounds, it seems to be accepted that Bourguiba ensured the status women hold in Tunisia today.

{12} Khul divorce is unilateral divorce for women, in which women have to forgo any claims to alimony from their husbands and custody of their children. The statement from Abidi thus signifies that there is no need for women to have this option, as women may instigate divorce without having to forgo alimony and/or custody.

{13} During fieldwork, the case of an Air Tunis stewardess who was fired because she wore a veil (hijab) to work was highlighted in the media and led to a rather heated debate in parliament.

{14} A 1981 law banned women from wearing the hijab in public offices, and a 1985 decree banned the hijab in educational establishments (Ben Salem 2010).

{15} The central disagreement that led to the breakdown was broader – whether sharia should be mentioned as the source for Tunisian legislation in the preamble or not. This is part of the discussion regarding Tunisia’s “identity” that has now moved into the courts.

{16} Afek Tounes is a central-right conservative, liberal, secular political party in Tunisia. Afek Tounes was formed post-revolution as the political landscape in Tunisia opened up as the old regime fell.

{17} According to Raoudha Abidi, head of the Judges Union, this means that the make-up of the eventual constitutional court will ultimately decide how the constitution plays out in everyday life.

{18} Interestingly, around the same time as this report is due to be finalized in mid-2016, the Ennahda party has announced that it will change its ideological basis and become a secular, conservative party.

2015: Transition, Islam, and the current Tunisian identity crisis

The Constituent Assembly adopted Tunisia’s new constitution in 2014. The constitution set forth a script for civic society and should therefore lead to comprehensive legal reform (as outlined in the constitution’s chapter on transition). Celebrated as a success of democracy and dialogue, great hopes are tied to its implementation.{19} Four provisions are particularly central to the status of women’s rights in Tunisia:

Art. 1

Tunisia is a free, independent, sovereign state; its religion is Islam, its language Arabic, and its system is republican.This article might not be amended.

Art. 2

Tunisia is a civil state based on citizenship, the will of the people, and the supremacy of law.This article might not be amended.

Art. 21

All citizens, male and female, have equal rights and duties, and are equal before the law without any discrimination.The state guarantees freedoms and individual and collective rights to all citizens, and provides all citizens the conditions for a dignified life.

Art. 46

The State commits to protecting women’s achieved rights and works to promote and develop them.The State shall guarantee equality of opportunity between men and women in the bearing of all responsibilities and in all fields.The State shall strive to achieve equal representation for women and men in elected councils.The State shall take the necessary measures to eradicate violence against women.

In the area of women’s rights, the 2014 constitution is more precise than the former 1959 constitution.{20} For example, the 2014 constitution mentions gender (“male and female”) in the clause concerning equality (art. 21), whereas the former constitution only states, “All are equal before the law” (1959 Const. art. 6). The 2014 constitution also includes specific language outlining the state’s commitment to protecting and developing women’s rights as well as eradicating violence against women (art. 46). Even though the former constitution also guaranteed equality, the 2014 constitution cements the state’s responsibility and commitment to guarantee women’s rights by expressly referring to “women.”

It is clear that post-independence Tunisia saw women’s status improve immensely. Tunisia’s women’s rights activists are very protective of the status they hold and committed to keeping their rights from being curtailed in any way (Charrad and Zarrugh 2014). In a sense, the debates and disagreements concerning the draft constitution were not intended to further women’s rights and position, but rather to make sure women’s rights and position were maintained. As Nadia Elboubkri (2013) mentions, women were sure of their status under the Ben Ali regime, and women as political actors formed part of the basis for the Ben Ali rule. Although women’s rights activists were part of the movement to topple the regime during the 2011 revolution, the fear of losing their stable position and rights fuelled the outrage expressed after the proposition of article 2.28. The scepticism expressed by civil society and women’s rights advocates regarding political Islamism, as well as Ennahda’s central position in the process of transition, was therefore a desire to maintain status quo.

The 2011 process that contributed the most to furthering women’s rights in Tunisia following the revolution was the push by women’s rights for Tunisia to lift all special reservations to CEDAW (HRW 2011). Tunisia’s lifting of special reservations to CEDAW was an important move, as it opens up the possibility for courts to overrule discriminatory laws even before a process of law review has been instigated. This is because the Tunisian constitution provides that international treaties and legal frameworks to which Tunisia is a signatory (such as CEDAW) are second only to the constitution in legal force. Such treaties take precedence over national law, and as Raoudha Abidi, head of Tunisia’s Judges Union, explained in an interview, this means that judges can apply CEDAW in cases where a Tunisian domestic law appears to be unconstitutional (i.e., in conflict with the constitution’s requirement of gender equality). I come back to this below.

Only time will tell, but Tunisia’s lifting of certain special reservations to CEDAW may allow courts to implement gender equality as stated in the constitution, and even to challenge controversial issues such as inheritance law. In addition, the constitution of 2014 obligates the state to combat gender-based violence and violence against women, which necessarily entail comprehensive efforts to ensure that women are able to gain the protection the law grants.

Remaining inequalities

In spite of the 2014 constitution’s mandate, inequities persist under Tunisian law. One of the most important is the issue of women’s unequal inheritance – a situation where the CSP employs Quranic legal principles (Charrad 2007; Ben Salem 2010; Chambers and Cummings 2014; see also CPS title IX, ch. III). Women also do not have an equal right to pass citizenship to a non-Tunisian spouse: in the case of a man marrying a non-Tunisian woman, citizenship is bestowed automatically, but a woman’s ability to pass on citizenship is conditioned upon whether the husband is Muslim (or has converted to Islam), where the husband resides, and whether the husband can speak Arabic (Ben Salem 2010). Informal conversations in Tunis during fieldwork for this report showed that Tunisian women who wish to marry non-Tunisian, non-Muslim men have to consider these issues before contracting marriage. Custody of children in the case of divorce is also problematic. Although the CSP provides that custody is to be granted based on the “child’s best interest,” a divorced mother who remarries will automatically lose custody of any children (CSP art. 58; see also Charrad 2007; Ben Salem 2010).

Interviewees highlighted a number of other issues of lingering inequality between men and women. For example, in spite of labour laws that mandate equal wages and access to employment, women are underemployed and have lower salaries than men (Chambers and Cummings 2014). Mériem Bourguiba also claimed that women working in the private sector are discriminated against in job interviews and in salary negotiations (interview 23 Apr. 2015).

Charrad (2007, 1526) mentions that women lack legal protection in cases of domestic violence, even though 1993 amendments to the penal code under Ben Ali criminalised such acts (Ben Salem 2010; interviews with Habiba Ben Guiza 24 and 29 Apr. 2014).{21} The 1993 amendments also provided for more severe penalties for battery should the victim be the attacker’s spouse (Ben Salem 2010, 5; interviews with Ben Guiza, supra). However, it is clear that women in Tunisia, as in many other places, often refrain from reporting domestic violence, and the police lacks the training and knowledge to investigate (ibid.; Ben Salem 2010, 10). In fact, according to Ben Salem, marital rape is not a crime in Tunisian law. This means that married women lack protection against sexual violence in the home, despite the fact that other laws regarding duties in the marriage do not require women to be obedient to their husbands.

According to Ben Salem (2010), AFTURD has undertaken two sizable studies{22} into the issue of gender-based violence, which are made use of by, amongst others, legal professionals (interviews with Ben Guiza, supra). According to Ben Guiza, who consulted the reports in between our interviews, the studies align with the majority of insights gathered through interviews conducted for this report: although women in Tunisia are granted equality in many aspects of everyday life, and have protections under the law, implementation of these rights and protections in everyday life may be limited by a whole array of societal and cultural factors.

Tunisia and Islam

Tunisia is often viewed as a secular country. However, as discussed throughout this report, Islam plays a central role in Tunisia. The 1959 and 2014 constitutions both provide for this role, and, consequently, the legal system is influenced and based on sources of Islamic law (see 1959 Const. preamble & art. 1; 2014 Const. preamble & art. 1). This is especially clear in the realm of family and personal status law and nowhere is as stark as in the CSP’s chapter on inheritance. The heritage and memory of the “golden age” of Islam and the Maliki fiqh plays a central role in the nation’s conception of itself and demonstrates how Islam is a basis of Tunisia’s state identity, even though its 2014 constitution proclaims that it is “a civil state based on citizenship, the will of the people, and the supremacy of law” (art. 2).

During the “golden age of Islam” (ca. 750–950, the period of the Islamic khalifat), Tunisia became a renowned centre for Islamic learning (Vikør 1993, 87), and continued to be a place for high Islamic learning, well into the 13th century. The celebrated Islamic scholar and historian, Ibn Khaldun (1332–1406), was born, raised, and educated in the Islamic learning centres of Tunisia and reportedly studied both in Kairouan and at the Zeitouna mosque in Tunis (Talbi 1986). Zeitouna University (no longer a madrasa-style institution) still exists today as a respected institution of learning, although it is no longer world-renowned (Melki 2012). The grand mosque in Kairouan also still stands as a centre of Islamic learning, although it no longer houses the university that was considered one of the finest places of learning in the world during Islam’s golden age (Julien 1970; Abun-Nasr 1987).{23} The Maliki fiqh was central in Kairouan. Knut Vikør (1993, 87) argues that the establishment of the early Tunis-based Aghlabib rule, and its scholars’ preference for the Maliki fiqh, proved definitive for the Tunisian state that was to come. He shows how the Maliki madhab (school of thought) was a counterweight to the khalif in Baghdad in the early days of the Aghlabib dynasty; eventually, the Maliki fiqh came to dominate all of Maghreb (ibid., 103). The proud heritage Tunisia’s own brand of Islam – the Maliki fiqh – thus contributes to keeping Islam and Islamic philosophy central to the history and identity of Tunisia today.

Central to the “folk” discourse regarding women’s legal status is the tale of the marriage of Amatu al-H’aqq in 1462; a 15th century Kairouanian jurist wrote an epistle based on this tale, outlining and defending a woman’s right to a binding stipulation of monogamy in a marriage contract (see Largueche 2010). This story was related to me several times throughout my month in Tunis – to show how Tunisia’s Islamic heritage and history legitimises a ban on polygamy in modern times. “Marriage kairouanais,” as Largueche argues, thus became part of the legal legacy of the Maliki fiqh in Tunisia. “The insertion of stipulations in the marriage contract, assuring women more security and autonomy, was not unknown in Islamic law, but in Kairouan it was a custom widely practiced backed by a legal rule” (ibid., 2–3). The existence of this Kairouanian tradition (‘amal) became a historical precedent for the later abolishment of polygamy in Tunisia’s civil law (the CSP). As Largueche (ibid., 5) shows, the common practice of including stipulations regarding monogamy in marriage contracts eventually led to the stipulation becoming standardised and named after the custom of Kairouan. The Kairouan marriage custom was also “women friendly” because it gave the existing wife the power to repudiate a potential second wife. This “the custom was adopted and it became part of the juridical practice” (ibid., 6).

Although Tunisia is in the midst of a so-called “identity-crisis” with regards to the role Islam should play today in the state structure and everyday life, reference is frequently made to Islam, and especially to the Maliki fiqh of Kairouan, when discussing women’s rights in national legislation. The use of this type of narrative to underline that the liberal status women have in Tunisia is also a legitimate Islamic practice shows that (even for secular politicians and women’s rights activists) persuasion in the form of religious legitimation is still central in Tunisian public debate. In this sense, the discourse in Tunisia is similar discourses concerning women’s status and rights in many other Muslim countries (Mir-Hosseini 1999; Tønnessen and Kjøstvedt 2010; Tønnessen 2011; Tønnessen and Al-Naggar 2013).

Giving historical and religious legitimacy to women’s equality and liberal gender politics in Tunisia means women’s rights activists have strong arguments when they work to maintain, and even further, the position of women in the country. In a country where political debates are often polarised along religious lines, “selling” women’s equality as something intrinsically Tunisian and part of a specifically Tunisian brand of Islam creates leverage.

However, this argument is also employed against equality. The inheritance articles of the CSP were discussed in an interview with two young female judges about inheritance law, and both maintained that the differences between men and women in issues of inheritance are fair because they are from the Quran (CSP title IX, arts. 91–121). When probed further, they maintained that the provisions come directly from God. Nonetheless, they also explained that families may circumvent this provision by writing a testament.

Tunisia’s state “identity”

Several of the individuals interviewed for this report mentioned “identity” – or a crisis of Tunisia’s identity – while discussing the process of transition and implementing the new constitution. By this they seemed to mean that Tunisia’s future identity as a nation is unclear because of the constitution’s ambiguous nature and the role of Islam in the state and public life. The constitution maintains that Tunisia’s religion is Islam, but it also proclaims that Tunisia is “a civil state based on citizenship, the will of the people, and the supremacy of law” (art. 2). This, along with the legal hierarchy set out in the constitution (art. 20), makes interpreting the constitution open to debate, as it is not clear if sharia or international treaties should take precedence as a source of law.

This debate is not between those asking for Islamic law and those wishing to completely untangle Tunisia from Islam. The issue of Tunisia being a Muslim majority state is a non-issue, and, as such, even the secular parties do not question the Islamic history of their nation. Political actors disagree about what constitutes sharia and whether or not Tunisia’s brand of sharia conforms to international human rights. Nevertheless, Tunisia’s concern for maintaining basic human freedoms, including the rights to free speech and religious freedom, means Islam should have a role to play in Tunisia. This was made very clear in interviews with Ennahda senior members, who experienced oppression on the basis of their personal and political activities under the old regime.

It is also clear that because the constitution does not expressly define the role of sharia in the legal system, Tunisia’s identity as a state has been moved out of parliament and into the courts. The final 2014 constitution drops any mention to sharia from the preamble and maintains that Tunisia is a “civil” state. However, it also proclaims that Tunisia’s religion is Islam (art. 1). In an interview, Rym Mahjoub Massmodi opined that this ambiguity was left in the constitution intentionally, so that it would pass through the largely Ennahda-dominated constituent assembly. The ambiguity allows lawyers to promote women’s rights in courts of law by arguing against the legality of applying discriminatory sharia principles. Similar ambiguities have been left to the courts to decide in other Muslim countries, suggesting that on this issue Tunisia is not exceptional, but rather is a typical case (see, e.g., Tønnessen 2011, discussing Sudan).

CEDAW and international treaties

International agreements approved and ratified by the Assembly of the People’s Representatives are superior to laws and inferior to the Constitution. (2014 Const. art. 20)

As Ms. Raoudha Abidi highlighted in an interview, Tunisia’s 2014 constitution opens up the possibility of overruling domestic law in questions concerning discrimination against women. International agreements approved and ratified by the Assembly of the Representatives of the People have a higher status than domestic laws, although they are still inferior to the constitution (the highest source of authority). This express declaration of the legal hierarchy is a new element of the 2014 constitution, even though Tunisian judges could look to international treaties and human rights frameworks even under the 1959 constitution (Ltaief 2005). What makes the post-revolutionary period extra interesting from a women’s rights perspective is the fact that this hierarchy was declared in the constitution around the same time that Tunisia dropped several special reservations to CEDAW.

Several researchers claim that Islamic law and gender equality are not in contradiction to each other (e.g., Mir-Hosseini 2004; Badran 2009). The use of and room for ijtihad (decision-making through independent reasoning) in Islamic law, and especially in the Tunisian legal system, gives room to ensure women’s equality in front of the law (Badran 2009). In an interview, Ms. Abidi very clearly elucidated how ijtihad can be employed within the framework of the Tunisian constitution in order to secure full gender equality. However, this depends on judges’ knowledge and will to interpret the law in this manner:

So, if there is a difference between the laws and the treaties, I am supposed to apply the treaties. Normally that is what we do… But it is not generalised. And that is the work that now we want to work on… So a lot of work needs to be done here. I’m not a feminist, but this is due to my long experience, I do think that it is mainly women who can advance women’s rights. (Interview with Abidi, 4 May 2015)

In legal arguments, concluding that something is “Islamic” or “in the Quran” may seem to be a final point to end disagreement. However, Tunisian judges are also trained in the methods and sources of Maliki fiqh, including ijtihad as part of the judicial process (interviews with Ben Guiza, 24 and 29 Apr. 2015). This allows space for both more liberal and more conservative interpretations of sharia when the civic law is unclear. Maaike Voorhoeve (2012, 202) refers to Tunisian family law as undefined as regards the use of “open norms,” which leads to judicial discretion (and along with it, the usage of suitable Maliki fiqh) becoming very important, especially in borderline cases. As a consequence, the outcome of a case may depend on the judge(s) presiding over it.

Importantly, even though Tunisia’s court system has a possibility for appeal, this is not a realistic option for all. If the losing party in the lower court lives in a remote area with limited infrastructure and access to public transportation, has limited financial resources, or has little education (resulting in a lack of knowledge about the opportunity of appeal), the ruling may never be challenged. Furthermore, the indeterminacies regarding mixed marriage (especially in the case of a Muslim woman and a non-Muslim man) are intentional; the law does not explicitly forbid such marriages, but unclear legal formulations or “open norms” allow judges to hinder such marriages, make them difficult, or disfavour the woman in succession and inheritance questions (Voorhoeve 2012). Nonetheless, these open norms also permit judges to interpret the law on the basis of international treaties, guaranteeing gender equality and the basic freedom to choose. For example, a number of rulings in Tunis during the late 1990s demonstrate that judges at that time were willing to interpret the law to allow Muslim women to marry non-Muslim men (Ltaief 2005).

Code of personal status: The case of unequal inheritance

The CSP is not perfect (although no country in the world has achieved reached gender equality; see GGGR 2014{24}), and women are still discriminated against in several areas. As mentioned, the issue of women’s unequal inheritance share is controversial and was highlighted in several interviews conducted for this report. Nonetheless, as Ms. Abidi explained, through implementing the new constitution, judges have been given a way to grant women equal shares in inheritance cases.

However, Ms. Abidi also emphasised that Tunisia’s laws are gender equal. As the constitution of 2014 spells out, all citizens – men and women – are equal (art. 21), and international treaty law is superior to domestic laws (art. 20). Thus, now that Tunisia has lifted a number of specific reservations to CEDAW, a judge can rule in a court of law that a woman should have an inheritance equal to that of a man – based on CEDAW’s stipulation that women and men have equal rights within the family (CEDAW art. 16), and in spite of the CSP’s stipulations. However, this presupposes that the judge is knowledgeable about this possibility, as well as willing to rule in this manner. Even female judges might not be willing to interpret the law in this way. For example, two young female judges who were interviewed opined that the CSP’s inheritance provisions are fair and in accordance with the Quran; they did not see why a woman would need to inherit more than one-half of a man’s inheritance share.{25}

When Ms. Abidi heard about the response from the two young judges, she replied that she wishes to found an association for female judges in order to train and educate young female judges on issues concerning women’s rights and how the law may be utilised to maximise the space available for reform. She explained, “Because we have figured out that a great number of female judges have no idea of the gender approach, so how would these women who are supposed to apply the law, apply [international] treaties, if they don’t know it?” (interview, 4 May 2015).

Implementation of Tunisia’s 2014 constitution is in motion. Among other things, a process is underway to review all domestic laws in Tunisia to screen for and ensure that gender equality is maintained. A constitutional court, which should soon be assembled, will be a central tool during this process and has the potential to ensure the constitutionality of Tunisian law. However, as activists maintain, the composition of sitting judges on the court will greatly affect the court’s success in this area, since the constitution was purposefully left ambiguous and the law is therefore open for interpretation. A fault line runs between two of the constitution’s declarations: that Tunisia is a “civil” state, but that Islam is the state religion. The notion of Islam as the basis for Tunisian law was left out of the preamble after a long process of debate – meaning the constitution could be used either to justify conservative interpretations of sharia or to overrule national law and employ international conventions such as CEDAW, depending on the judges’ degree of conservatism and political background.

The role of judges

In Tunisia, as in many other places, judges play a very important role in implementing the law by interpreting it in court in the context of specific cases. However, this also means that the judgement in a particular case may vary depending on the judge. Even though a system of appeal is available, because appellate courts are few and far between, this system discriminates against those who live far from regional centres and who do not know of or understand the legal system. Voorhoeve (2012) mentions that judges in Tunisia are not bound by legal precedent, although they tend to abide by prior rulings from Tunisia’s Court of Cassation, simply because they would not wish to see their decisions overturned on appeal. This conflicts with what lawyer Habiba Ben Guiza told us in interviews: she believes many rural women are not in a position to appeal because of lack of access to the appellate system and, therefore, unfair rulings against them remain. According to her, although Tunisia is considered a liberal country, where women enjoy freedoms and welfare services not provided women in other Muslim countries, the lack of state funding for services means some women miss out and become increasingly marginalised when gender intersects with poverty, geographical location, or other discriminatory dimensions.

{19} The 2015 award of the Nobel Peace Prize to the National Dialogue Quartet demonstrates international approval of the process that resulted in the constitution Tunisia has today.

{20} Constitution of the Republic of Tunisia of 1959 [hereinafter 1959 Const.], http://unpan1.un.org/intradoc/groups/public/documents/cafrad/unpan004842.pdf.

{21} Prior to the amendment, “honour crimes” were included in the penal code and had reduced penalties.

{22} Also see Violations flagrantes des droits et violences à l’égard des femmes au Maghreb (Tunisie, Algérie et Maroc), 1996/1997 and Les Maghrébines, entre violences symboliques et violences physiques (Tunisie, Algérie, Maroc) 1998–1999, see http://www.afturd-tunisie.org/14-2/ for more information.

{23} See http://www.ceik.rnu.tn/Site_en/index.php.

{24} http://www3.weforum.org/docs/GGGR14/GGGR_CompleteReport_2014.pdf

{25} One judge was in expedited training and the other had 10 years of experience.

Conclusion

Over its history from the Bourguiba regime to the present, the women’s movement in Tunisia has become progressively more independent and more influential in Tunisia’s general political environment. The status of women has been important to Tunisia’s national identity throughout the country’s post-colonial history, and this status was a part of political projects under both Bouruiba and Ben Ali. As a result, women in Tunisia now enjoy unprecedented rights compared to women in other Muslim countries. However, it was not until the 2011 revolution that the women’s movement became fully independent from the state.

Since the revolution, a central focus of the women’s movement has been safeguarding and protecting the status women in Tunisia already have. Following the 2012 collapse in national dialogue surrounding the drafting of a new constitution, it became clear that women’s status is entangled with wider debates concerning Tunisia’s identity as a nation. Disagreements during the 2012 drafting process primarily concerned the role Islam was to play in the Tunisian constitution, but the proposal of article 2.28, setting out “complementary” family roles for men and women, became a national (and even international) rallying cry and showed how powerful the post-revolutionary Tunisian women’s movement can be.

Since adoption of the 2014 constitution, women activists and legal practitioners seem confident that they have the tools at hand to safeguard – and even further – the position of women in Tunisia. The deletion of draft article 2.28 and the inclusion of articles 21 (setting forth equality of men and women) and 46 (committing to strength women’s rights) are seen as victories for the women’s movement. More importantly, Tunisia’s removal of special reservations to CEDAW opens up the possibility for judges to rule in favour of full equality for women in cases where domestic law still lags behind international standards. Nonetheless, for this to happen, judges (including female judges) need to be educated about the possibilities for women’s advancement under the legal system. As the head of the Judges Union has states, “It is mainly women who can advance women’s rights” (interview with Abidi, 4 May 2015).

Literature list

Abun-Nasr, J. M. (ed.). 1987. A History of the Maghrib in the Islamic Period. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Antonakis-Nashif, A. 2016. Contested transformation: mobilized publics in Tunisia between compliance and protest. Mediterranean Politics, 21, no. 1: 128–149.

Barany, Z. 2011. “The Role of the Military.” Journal of Democracy 22, no. 4: 24–35.

Ben Salem, L. 2010. “Tunisia.” In Women’s Rights in the Middle East and North Africa: Progress Amid Resistance, edited by S. Kelly and J. Breslin, 1–29. New York: Freedom House.

Cavatorta, F., and R. H. Haugbølle. 2012. “The End of Authoritarian Rule and the Mythology of Tunisia under Ben Ali.” Mediterranean Politics 17, no. 2: 179–195.

Chambers, V., and C. Cummings. 2014. Building Momentum: Women’s Empowerment in Tunisia. Case Study Report. London: Overseas Development Institute. http://iknowpolitics.org/sites/default/files/tunisia_case_study_-_full_report_final_web.pdf.

Charrad, M. M. 1997. “Policy Shifts: State, Islam, and Gender in Tunisia, 1930s–1990s.” Social Politics 4, no. 2: 284–319.

———. 2007 “Tunisia at the Forefront of the Arab World: Two Waves of Gender Legislation.” Washington and Lee Law Review 64: 1513–1527. http://scholarlycommons.law.wlu.edu/wlulr/vol64/iss4/11/.

———. 2012. “Family law reforms in the Arab world: Tunisia and Morocco.” Report for the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA), Division for Social Policy and Development, Expert Group Meeting, New York.

Charrad, M. M., and A. Zarrugh. 2013. “The Arab Spring and Women’s Rights in Tunisia.” E-International Relations. http://www.e-ir.info/2013/09/04/the-arab-spring-and-womens-rights-in-tunisia/.

———. 2014. “Equal or Complementary? Women in the New Tunisian Constitution after the Arab Spring.” Journal of North African Studies 19, no. 2: 230–243.

Eich, T. 2009. “Induced Miscarriage in Early Mālikī and Ḥanafī Fiqh.” Islamic Law and Society 16, no. 3/4: 302–336.

Elboubkri, N. 2013. “Caught between Two Identities: Women’s Movements in Morocco and Tunisia.” Fair Observer. http://www.fairobserver.com/region/middle_east_north_africa/caught-two-identities-womens-movements-morocco-tunisia-part-1/.

Goulding, K. 2011 “Tunisia: Women’s Winter of Discontent.” openDemocracy 50.50. https://www.opendemocracy.net/5050/kristine-goulding/tunisia-womens-winter-of-discontent.

Gray, D. H. 2012. Tunisia after the Uprising: Islamist and secular Quests for women’s rights. Mediterranean politics, 17, no. 3: 285–302.

Hessini, L. 2007. “Abortion and Islam: Policies and Practice in the Middle East and North Africa.” Reproductive Health Matters 15, no. 29: 75–84.

HRW (Human Rights Watch). 2011. “Tunisia: Government Lifts Restrictions on Women’s Rights Treaty: To Complete Process, Revise Laws to Remove Discriminatory Provisions.” https://www.hrw.org/news/2011/09/06/tunisia-government-lifts-restrictions-womens-rights-treaty.

Joseph, S. 1993. “Connectivity and Patriarchy among Urban Working-Class Arab Families in Lebanon.” Ethnos 21, no. 4: 452–484.

———. 1994. “Brother/Sister Relationships: Connectivity, Love and Power in the Reproduction of Patriarchy in Lebanon.” American Ethnologist 21, no. 1: 50–73.

Julien, C. A. 1970. History of North Africa: Tunisia, Algeria, Morocco. From the Arab Conquest to 1830. New York: Praeger.

Khalil, A. 2014. “Tunisia’s Women: Partners in Revolution.” Journal of North African Studies 19 no. 2: 186–199.

Khosrokhavar, Farhad. 2012. The New Arab Revolution that Shook the World. London: Paradigm Publishers.

Labidi, L. 2007. “The Nature of Transnational Alliances in Women’s Associations in the Maghreb: The Case of AFTURD and ATFD in Tunisia.” Journal of Middle East Women’s Studies 3, no. 1: 6–34.

Largueche, D. 2010. “Monogamy in Islam: The Case of a Tunisian Marriage Contract.” Paper no. 39 (unpublished). https://www.sss.ias.edu/files/papers/paper39.pdf.

Ltaief, W. 2005. “International Law, Mixed Marriage, and the Law of Succession in North Africa: ‘… but some are more equal than others.’” International Social Science Journal 57, no. 184: 331–350.

Mashhour, A. 2005. “Islamic Law and Gender Equality: Could There Be a Common Ground?: A Study of Divorce and Polygamy in Sharia Law and Contemporary Legislation in Tunisia and Egypt.” Human Rights Quarterly 27 no. 2: 562–596.

Melki, W. 2012. “Zitouna Mosque Resumes Islamic Teaching after 50 Years.” Tunisialive. http://www.tunisia-live.net/2012/04/04/zitouna-mosque-resumes-islamic-teaching-after-50-years/.

Mir-Hosseini, Z. 1999. Islam and Gender: The Religious Debate in Contemporary Iran. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Moghaddam, V. 2005. “Tunisia.” In Women’s Rights in the Middle East and North Africa: Citizenship and Justice, edited by S. Nazir and L. Tomppert, 295–312. New York: Freedom House.

Murphy, E. C. 2003. “Women in Tunisia: Between State Feminism and Economic Reform.” In Women and Globalization in the Arab Middle East: Gender, Economy, and Society, edited by E. A. Doumato and M. P. Posusney, 169–194. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner.

Perkins, K. J. 2014. A History of Modern Tunisia. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Schraeder, P. J., and H. Redissi. 2011. “Ben Ali’s Fall.” Journal of Democracy 22, no. 3: 5–19.

Talbi, M. 1986. “Ibn Khaldun.” In The Encyclopaedia of Islam, vol. III, H-Iram, edited by B. Lewis, V. L. Menage, C. Pellat, and J. Schacht, 825–831. Leiden: Brill.

Tchaïcha, J. D., and K. Arfaoui. 2012. “Tunisian Women in the Twenty-first Century: Past Achievements and Present Uncertainties in the Wake of the Jasmine Revolution.” Journal of North African Studies 17, no. 2: 215–238.

Tjomsland, M. 1992. “Negotiating the ‘In-between.’ Modernizing Practices and Identities in Post-colonial Tunisia.” CMI Report R 1992: 10. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI). http://www.cmi.no/publications/1428-negotiating-the-in-between.

Tønnessen, L. 2011. “Feminist Interlegalities and Gender Justice in Sudan: The Debate on CEDAW and Islam.” Religion and Human Rights 6, no. 1: 25–39.