Women on the Bench in Angola

Why women judges are important

Women in the Angolan judiciary

Demand: Post-war expansion of the judiciary

Supply: Professionalization of the courts has favoured women

Merit-based recruitment favoured women

Extreme presidentialism, the ruling party, and the judiciary

Is merit sufficient to become a high court judge?

Websites, sources, and selected references

How to cite this publication:

Aslak Orre, Elin Skaar, Margareth Nangacovie (2025). Women on the Bench in Angola. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI Insight 2025:06)

Women have made a forceful entrance into the Angolan judiciary since Independence fifty years ago. Thousands of women have moved through law school; hundreds on to the bench; and quite a few to the two highest courts – including to top leadership positions. Across all court levels, women now make up around nearly half of all judges in Angola. This compares favourably with most neighbouring African countries as well as with well-established democracies in other parts of the world.

How do we explain the influx of women judges in Angola, in a context of post-war reconstruction? In this Insight, we suggest that we need to examine both the supply of eligible law candidates and the demand for judges.

Why women judges are important

Since studying women judges became a scholarly undertaking in the 1980s, feminist scholars have made three main arguments for why more women on the bench is a good thing:

- For reasons of diversity and representation – a more representative judiciary is a better judiciary, ensuring legitimacy and perceived access to justice.

- Because women are different, that is, women judges rule differently from their male counterparts. In matters such as sexual violence and family disputes, women and men judges may come to different judicial outcomes.

- For reasons of fairness. Women make up 50% of the population, so it is only right and fair that they make up half of judges too.

Women in the Angolan judiciary

After the end of a long-lasting, devastating civil war (1975-2022), which left the court system inherited from the Portuguese in shambles, Angola has gradually built and developed an increasingly functioning court system, where women judges have started to play an increasingly important role. When Angola established its own Supreme Court in the midst of the civil war, the first appointed Vice-President to the Court was a woman: Maria do Carmo Medina. No doubt, Medina set a precedent for future women judges in Angola. Currently, eight of the 22 Supreme Court judges (36%) and five of the eleven judges (45%) on the Constitutional Court are women. In fact, three years ago the Angolan Constitutional Court was one of the most women dominated high courts in the world, headed by its first female President; Laurinda Cardoso. In short, Angola has a higher percentage of women on the high courts – and in leadership positions – than nearly all other African countries. The share of women judges also compares favourably with other regions of the world. For instance, the overall percentage of women judges in Angola is equal to that of Australia and Latvia and higher than in seasoned democracies with long democratic traditions like the United States, England, and Norway.

Demand: Post-war expansion of the judiciary

We can trace the history of women’s role on formal courts in Angola through critical junctures in the development of the current court system, which we may divide into three main phases. Women judges had no role in the first phase (pre-independence); a minor role in the second phase (civil war); and an increasingly dominant role in the third phase (post-war reconstruction).

Phase 1: Pre-independence (colonialism–1975). Portuguese colonialism restricted the use of formal (i.e. state run) courts – including an appellate court – to European settlers. For most Africans, legal disputes were settled in courts of traditional/customary law throughout the country. There were no law schools in Angola, so all lawyers (and therefore also judges) received their education in Portugal – or in Brazil; another Portuguese former colony with an inherited civil-law legal system.

Phase II: Independence and civil war (1975–2002). When the Portuguese pulled out of Angola in 1975, the formal court system had to be built from scratch by the new government (formed by the MPLA, Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola), as most of the few lawyers and judges who lived in Luanda had fled the country. Yet, the civil war that immediately broke out complicated this (re)construction process. The first legal institutionalisation of formal courts took place in 1979. With ideals of a socialist state justice system, the Popular Revolutionary Courts were created in Luanda and in some provinces. The first contours of a more politically independent, three-layered justice system came in 1988, when a unitary justice system and the Supreme Court was founded. It envisioned a three-layered court structure: Below the Supreme Court, the courts would mirror the state administration, with 18 provincial courts and 187 first instance (município) courts at the sub-provincial level.

The liberal-democratic Constitution of 1992 introduced multiparty elections and formalised, for the first time, three independent branches of the state and the rule of law with checks and balances. However, when the civil war finally came to an end in 2002, the new court system was in miserable shape. Only a handful of the município courts were operative, and the provincial courts were partly operative only in some provinces.

Phase III: Post-war period (2002–). With peace, and rapidly increasing oil wealth, the (re)construction of the courts started in earnest after 2002. At the top level, many judgeships became available over the years as the Supreme Court increased the number of judges from seven to 18. Each judge is appointed for seven years, and the mandate is non-renewable. The Constitutional Court was established in 2008 to act as the guardian of the constitutional order. It too needed highly qualified judges and actively recruited women from the very start. Until 2022, women constituted the majority (7 of 11) judges on the Constitutional Court. The rest of the lower court system has expanded too, creating hundreds of new positions for judges.

The most recent reform process – which started in 2015 and which is not yet completed – retains a three-levels court system, but separated from the state administration. The mostly inoperative município courts are gradually being replaced by 62 first instance courts in court districts called comarcas. The 19 provincial courts are being replaced by so-called Tribunais da Relação, which will function as appellate courts in five large judicial regions. Each Tribunal da Relação is much larger than the provincial courts. Each court will have more than twenty judges ruling in specialised chambers, covering administrative, criminal, civil, family, labour, and taxation matters respectively.

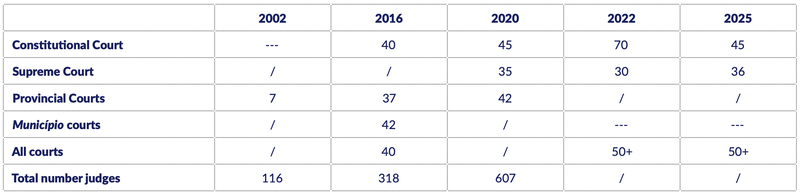

Table 1: Angolan courts and women judges – a schematic historical overview

Source: Table prepared by authors.

The entry of women judges after 2002 has grown remarkably – at all court levels. In 2016, when the first report with reliable numbers on judges was published, the functioning município courts reported 42 per cent women. At the provincial level, the share of women judges was slightly lower, but increased to 42 per cent in 2020. As Table 2 below shows, women have been very well represented on the two highest courts.

Table 2: Women judges in Angola, in % of total

Notes: / not available; --- not applicable.

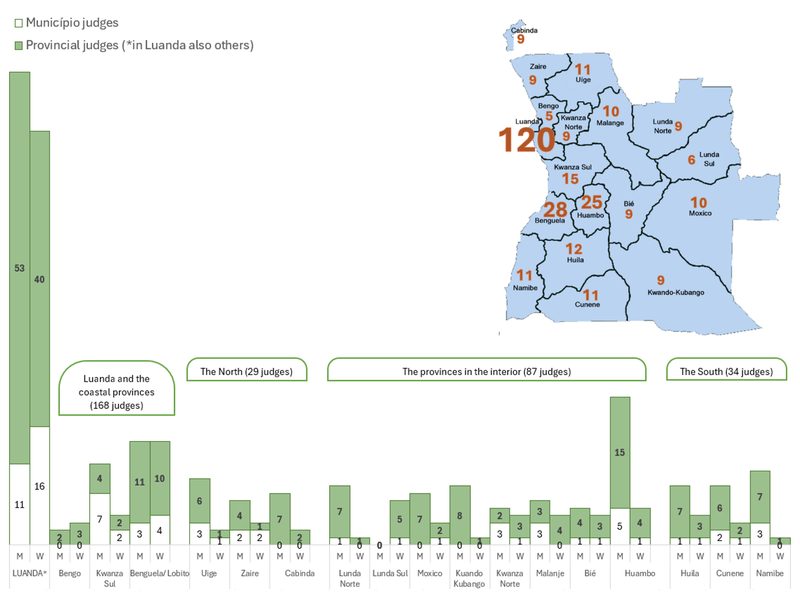

Although the overall number (and percentage) of women judges in Angola is high across the courts at all levels, the overwhelming majority of judges live and work in the capital, Luanda. This is mainly because the number of judges across Angola’s 18 provinces varies hugely. Judgeships are thus available just in a small number of courts in only some provinces. According to a report by the AJPD, an NGO active in the justice sector, only three provinces had 15 or more judges at the município and provincial levels combined in 2016: Luanda (120 judges), Huambo (25 judges) and Benguela (15 judges). Nine provinces had ten judges or less. A third of Angola’s population of roughly 37,8 million people lives in the capital. Nevertheless, access to justice (at least through the formal court system), is illusory for most Angolans. The super-concentration of judgeships in Luanda, also means that judges have a very limited choice of where to work.

Figure 1: Distribution of judges by court level and by gender across Angola’s 18 provinces (2016)

Source: AJPD (2017.

Notes: M=men, W=women

Regarding the gender balance at the município (first instance court) level, in 2016 seven provinces did not have a single woman judge while eight provinces had only one woman judge each. Importantly, women judges outnumbered men in the município courts of Luanda and Benguela. In several provincial courts, women were slightly better represented, even outnumbering male judges.

Supply: Professionalization of the courts has favoured women

In addition to the creation of new courts and the increase in the number of judgeships at all court levels, there has been a continuous process of professionalising the courts. Two important developments have favoured women during this process: 1) their access to law schools and 2) the improvements of merit-based recruitment systems at the lower courts’ level.

More women law graduates

A prerequisite for having women on the bench is that there is a pool of candidates to draw from. The first Law Faculty in Angola was opened only in 1985 at the public university Universidade Agostinho Neto. This university has educated most Angolan senior judges, including most of the women judges serving on the Supreme Court and Constitutional Court. The number of law schools in Angola has grown from one to ten since 1985, providing ever more students with the career options of becoming lawyers, prosecutors or judges. Women make up an increasingly larger proportion of law school graduates, moving in the direction of gender parity. This has taken place without quota systems for university entrance. Women have tended to do well in law schools, and judgeship seems to have been a particularly popular career path for women with law degrees.

Merit-based recruitment favoured women

For several decades, judges received no particular training beyond law school. In the early 1990s, there were still judges in lower-level courts without law degrees. During the early period of establishing and developing the formal courts system, loyalty to the ruling party, MPLA, had bearings on whether a young law school graduate would be appointed to a judgeship. However, as the number of law schools increased, law degrees became a requirement for becoming a judge.

The recruitment system for judges was further formalised when a special school for the training of judges was established under the University of Agostinho Neto in Luanda in 2002. The National Institute for Judicial Studies (Instituto Nacional Estudos Judiciários), INEJ, offers eight-months training courses for law school graduates who wish to become judges. A woman lawyer veteran and later judge was invited to head INEJ. Entry exams to INEJ are based on merit. The candidates who graduate from INEJ with the best grades, get to choose first where they want to work. However, the National Judicial Council (Conselho Superior da Magistratura Judicial) ultimately decides where the judge gets their first three-year service. After this years of on-the-ground practical training – the judge can apply to be transferred to another court. Most judges choose to go back to Luanda.

The introduction of a merit-based recruitment system has undoubtedly benefitted women. As women make up a larger proportion of law student graduates, it is assumed that gradually there will also be a larger share of women on the bench. Women have tended to do well in law school in Angola. Thus, women have gained access to, and graduated from, INEJ in increasingly large numbers. Interestingly, both male and female judges seem to agree in personal interviews with the authors of this Insight that women students are, on the average, more hard working and more diligent than their fellow male students – and therefore end up getting better grades. Consequently, they have been rewarded with access to the bench.

Extreme presidentialism, the ruling party, and the judiciary

The influx of women into the Angolan judiciary has taken place in an intense phase of post-war reconstruction and gradual democratisation, in a state dominated by the ruling party, MPLA and the personal power of José Eduardo Dos Santos, MPLA head.Dos Santos served as president for 38 consecutive years (1979–2017) and dominated both politics and the judiciary. Taking over from Dos Santos in 2017, João Lourenço is also the president of MPLA, just like his predecessor. The intertwining of the ruling party and the state thus continues – to the point that some scholars refer to Angola simply as a party state, not only a one-party state.

Is merit sufficient to become a high court judge?

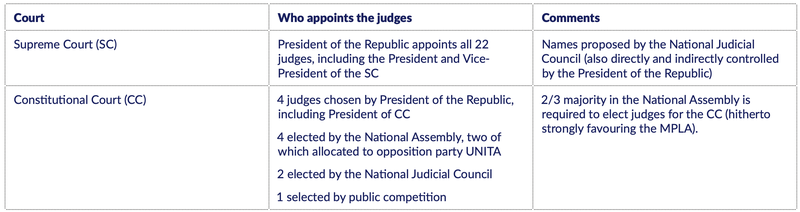

Despite improved education for judges and merit-based recruitment at the lower tiers, the extremely centralised appointment system for high court judges ensures that the President of the Republic retains close control over all appointments to the Supreme Court and most appointments to the Constitutional Court (see Table 3 below).

Table 3: Appointment procedures to Angola’s high courts

Source: Constitution of Angola, articles 180–183.

Thus, there is a strong liaison between MPLA politics and the judiciary. As in other strongly presidentialist systems with centralized appointment procedures, the President of the Republic has the power to appoint those who are most loyal to him. There is evidence that the Supreme Court has been staffed by MPLA supporters and presidential loyalists over the years. This applies to men and women judges alike.

The expansion and professionalisation of the courts in Angola have no doubt favoured the entry of women judges. To have access to the two top courts, party loyalty to the MPLA is arguably an additional requirement. The obvious exception are those women who have been appointed by UNITA on its parliamentary quota.

Final reflections

We have offered two prime arguments for the incursion of women into the Angola court system: The increasing supply of women law students and later INEJ graduates on the one hand, and the strong demand for judges as the justice system expanded after the war, on the other.

Our findings are in line with scholars who have argued that situations of political rupture – such as civil war – generally create new opportunity structures, some of which may favour the entry of women into public positions of power. We have found that the constant need for more judges is likely to have made the inroads to the judiciary easier for women in post-conflict Angola than in countries with well-established court systems where judicial positions are already filled by men, where openings in the system are few, vacancies are open to strict competition, and access is regulated by a series of formal as well as non-formal rules – often controlled by men.

One interesting question remains: Why did not men fill all the many vacant positions in Angola? Although women are not only well represented in the judiciary but also in politics – even at the minister level – Angola is not considered a particularly a “gender-friendly” country. In fact, Angola scores quite low on the UNDP indices for gender parity and gender-based disadvantage. Why would not the overall gender disparities in the country also be reflected in the judiciary?

One prominent hypothesis is that the judiciary is intimately linked with the MPLA, the state, and the elite. MPLA’s historical heritage as a Marxist-Leninist liberation movement, imbued with a strong ethos of gender-equality, may arguably have favoured the entry of women to the Angolan judiciary. Women held some central roles in the MPLA from its days as a liberation movement and organised a separate women’s wing (as did UNITA). As the MPLA movement turned into a political party, women too gained higher political positions. So far, both dos Santos and Lourenço have appointed women to the two high courts. Though the appointment system is obviously detrimental to de facto judicial independence, there is no basis for claiming that it has been to the detriment of women judges.

The entry of women to the bench in Angola in numbers approaching gender parity is positive for a number of reasons, such as diversity and representation; potential increased sensitivity to gender specific issues (such as gendered violence); and for the simple sake of fairness. However, we would like to stress that a more gender balanced judiciary cannot alone resolve the political bias of the Angolan judiciary, nor its related problems of legitimacy and capacity. According to recent Afrobarometer surveys, the majority of Angolans consider the possibility of receiving justice when needed as improbable. The low number and geographically unequal spread of courts, poorly staffed and with scarce resources, also means low access to courts/justice for most Angolans. In addition, the justice system is plagued by corruption. The alleged involvement of women high court judges in ongoing corruption cases suggests that striving for gender balanced courts, however important, is not a fix-all.

Websites, sources, and selected references

Note that reliable statistics on judgeships and gender in Angola are simply not available. In this Insight, as summed up in Table 2, only anecdotal evidence of the total number of judges is available for 2002 (the time of the final peace agreement). 2016 figures are found in and AJPD report (2017 : 96-104); to date the only existing comprehensive overview of Angolan courts and share of women judges. 2020, 2022 and 2025 figures are based on interviews undertaken by the authors with judges and people in the legal sector, including the Angolan Association of Judges.

Reports

AJPD (Justice Peace and Democracy Association). 2017. Angola: The Justice System, Human Rights and the Rule of Law. edited by Lucía da Silveira e António Ventura. Luanda.

INE - Angola. 2020. Relatório Tématico Sobre o Genéro. Inquérito de despesas, receitas e emprego em Angola 2018-2019. Edited by Channey Rosa John. Luanda: Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE) - Angola. https://www.ine.gov.ao/Arquivos/arquivosCarregados/Carregados/Publicacao_637692040601799697.pdf

Home pages for the High Courts

The Constitutional Court:

https://www.tribunalconstitucional.ao

The Constitution of the Republic of Angola:

https://www.tribunalconstitucional.ao/pt/artigos-da-constituicao/

Selected references

Bauer, Gretchen, and Josephine Dawuni, eds. 2016. Gender and the judiciary in Africa: from obscurity to parity?, Routledge Research in Gender and Politics. New York and London: Routledge.

Dawuni, Josephine Jarpa, ed. 2022. Gender, Judging and the Courts in Africa: Selected Studies: Taylor & Francis.

Dawuni, Josephine, and Alice Kang. 2015. “Her ladyship chief justice: the rise of female leaders in the judiciary in Africa.” Africa Today 62 (2):45-69.

Escobar-Lemmon, Maria C, Valerie J Hoekstra, Alice J Kang, and Miki Caul Kittilson. 2021. “Breaking the judicial glass ceiling: The appointment of women to high courts worldwide.” The Journal of Politics 83 (2):662-674.

Kenney, Sally Jane. 2013. Gender and justice: Why women in the judiciary really matter. New York and London: Routledge.

Tripp, Aili Mari. 2015. Women and Power in Postconflict Africa, Cambridge Studies in Gender and Politics: Cambridge University Press