Civil Society and Social Movements in Contemporary Angola: We Are Civil Society

How to cite this publication:

Inge Amundsen, Cesaltina Abreu, Catarina Antunes Gomes (2025). Civil Society and Social Movements in Contemporary Angola: We Are Civil Society. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI Insight 2025:05)

Civil society in Angola operates under increasing repression. This CMI Insight highlights findings from a study mapping how formal and informal groups across all provinces organise, act, and survive.

Key Messages

Illiberal legislation and government control are severely restricting the mass media, curtailing the freedom of expression and association in Angola.

During the 2022–2024 period we conducted a survey mapping these organisations and movements with a view to understanding who they are, their foci, perceptions and strategies.

We found that:

- Civil society organisations and movements are found throughout Angola, in all 18 provinces.

- Most of the organisations are relatively small, providing flexibility while at the same time making them vulnerable.

- 48% of the organisations are “social development” organisations addressing economic development, environmental protection, local projects, humanitarian support, etc. 42% are “political intervention” organisations engaged in promotion of democracy, citizenship, human rights, and free and fair elections.

- The organisations and movements are democratically managed, through majority or consensus decisions.

- Members of most of the organisations comprise more men than women; women are more engaged in social development activities than political issues.

- The survey respondents exhibited overall a very negative view of the government. Opinions on the legal framework and parliament were even more negative.

- The presidency/government of President Lourenço is believed to be no better than the previous administration.

- Two of the survival strategies of the organisations in the hostile political climate in Angola include collaborating with others in networks and alliances. and forming informal movements instead of formal organisations.

Why? The Background

In 2023 we assessed the Angolan government’s proposed new law regulating the NGO sector. We found it would further restrict the space for NGOs and oppositional voices in Angola (Gomes et al. 2023). This law was ratified by President Lourenço in May 2025, despite local and international protests. Shortly before ratification, in August 2024, the Angolan president also approved the Law on the Crimes of Vandalism of Public Goods and Services, which allows prison sentences of up to 25 years for participants in protests that result in vandalism and service disruptions. Furthermore, the National Security Law permits excessive government control over the mass media, civil society organisations, and other private institutions (HRW 2025).

This recent legislation is the latest phase in a long trend of legislation severely limiting the operational space for the mass media, curtailing freedom of expression and association in Angola. Already in 2006, we pointed out the limited legal space for non-governmental organisations and association in Angola, and the “deliberate policies of restricting the room for manoeuvre, controlling the operations and limiting the political impact of civil society organisations” (Amundsen and Abreu 2006).

Hence, as part of the collaboration between Angolan and Norwegian researchers in the programme titled Enhancing the Research Environment in Angola through Capacity Development 2019-2024, we embarked in 2022 on a broader Study on Civil Society, Social Movements and Activism in Angola. The aim of that study was to map the existence and various forms of civil society organisations and movements in Angola, their profiles and areas of work, to understand their self-perceptions, and to probe their views on politics and development, and not least their strategies in a hostile political environment.

How? The Survey

Our survey began in 2022 with informal conversations with civil society activists throughout the country as well as with resource people in Luanda to design a questionnaire relevant to our inquiries and to the realities and concerns on the ground. We conducted eight in-depth interviews to test whether the questionnaire was relevant, understood, and served our objectives before identifying organisations, movements and activists as respondents. Thereafter the questionnaire was sent out in two rounds to 200 organisations, movements and activists in early and late 2022. Ultimately, we received 139 completed and valid questionnaires.

Please note that the survey results are not representative of Angolan civil society in a strict scientific sense and should not be generalised to reflect all of Angola’s civil society. It proved impossible to cover allorganisations and movements in the country; it was even impossible to identify all of them because of the fluid nature of social movements. Therefore, the selection of respondents was to some extent based on relevance and accessibility, as well as self-selection by the respondents.

However, parallel to the analysis of the data from the survey, we held a series of five regional meetings, three cycles of public debates, ten simultaneous debates and two national meetings with 747 members of the organisations in late 2023 and early 2024. Thus, a qualitative and participatory element was added to the survey data. The regional meetings provided a deeper understanding of the respondents and their opinions and perceptions. As the participants at those events were able to express themselves freely, we could collect a broader and deeper set of reflections on the questions covered by the survey, and on various other issues of concern.

Therefore, we believe our study of civil society in Angola provides a deep and broad mapping of social activism, and information on the structures, work areas, opinions, and strategies of civil society in Angola. To our knowledge, this is the most comprehensive study of Angolan CSOs and movements to date – covering all 18 provinces in the entire country. The full study will be published in mid-2025. The data presented in this paper is a preliminary snapshot of the survey findings.

Where and What?

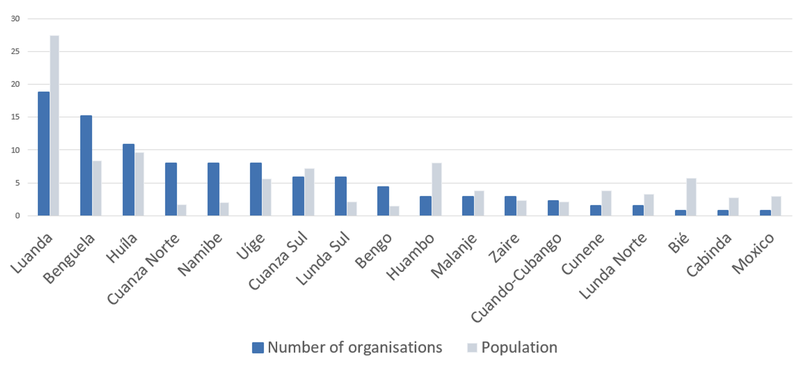

Figure 1: Where?

Civil society organisations and movements are found throughout Angola, in all 18 provinces (blue columns). In our sample, the largest number of organisations operate in Luanda, Angola’s capital and by far the country’s largest city.

However, relative to 2022 population size in each province (grey columns) (Statista 2025), it is evident that Luanda is underrepresented in our sample in terms of number of organisations (27% of the population but only 19% of the organisations). Likewise, Huambo and Bié are significantly underrepresented, whereas Benguela, Cuanza Norte and Namibe are clearly overrepresented.

Some basic findings emerge. Civil society and social movements, in a plurality of organisational forms, are distributed throughout the country. Civil activism is rooted in local contexts, and peoples’ experiences of daily lives lead to the articulation of their concerns into organised action.

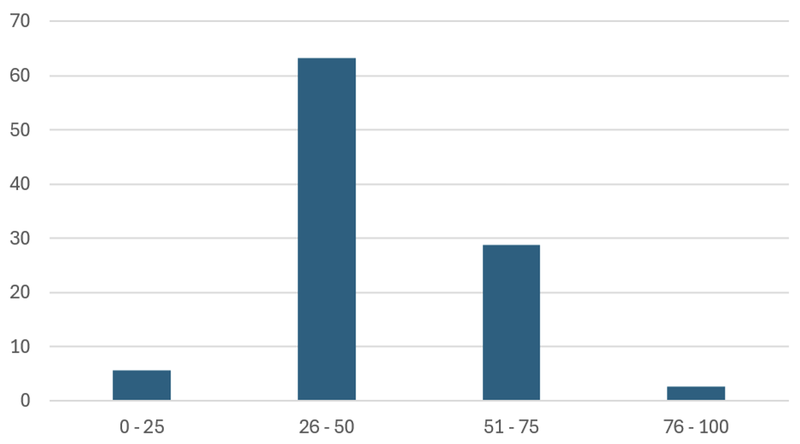

Figure 2: How Big?

How big are the organisations in terms of membership? According to the survey, most of the organisations (over 60%) are relatively small with 25-50 members. A little less than a third (29%) are medium sized with 51-75 members. Only a few organisations in our sample are very small (6% have fewer than 25 members) and even fewer organisations are big (only 2% have more than 75 members). There were no organisations with more than 100 members in our sample.

The fact that most organisations are relatively small provide flexibility, while at the same time making them vulnerable. Some of the respondents noted that size also reflects a general lack of public as well as international funding for civil society organisations and their projects. Civil society organisations lack human resources, knowledge, and impose very low membership fees, if at all. Access to funding often depends on subcontracting from bigger NGOs and international agencies for project work. Also, propensities of splits and fractioning were noted by some respondents.

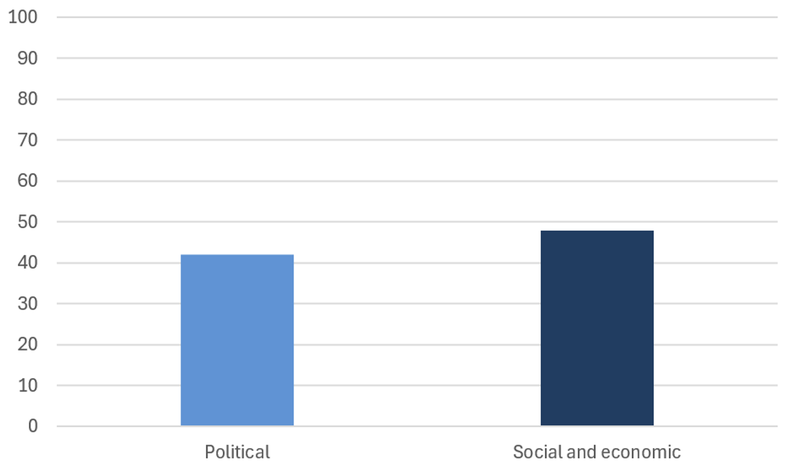

Figure 3: Main Focus

What are the CSOs doing? On the question of their predominant activity, 48% of the organisations responded “social development”, which includes economic development and environmental protection, implementation of local development projects, humanitarian support, protection of minorities and the marginalised, art, culture, sports, etc. By contrast, 42% of the CSOs reported “political interventions”, which include promotion of democracy, citizenship, human rights, and free and fair elections. In other words, the majority of Angola’s civil society organisations are engaged in social development. An almost equal proportion is engaged in activities of a political nature.

How democratic are the organisations internally? The survey suggests that they are democratically governed. Two-thirds (65.6%) reported that decisions were made by majority, while one-third (32.8%) said decisions were made by consensus (unanimity). Only a small fraction, 1.6%, reported that decisions were made by the leader of the organisation.

How are the organisations financed? Basically, they have managed to maintain activities on very small budgets based on irregular, voluntary contributions from activists themselves and private donations – rather than regular membership fees. They also reported that public funding and support from international sources account for very little. They are not receiving any public grants, and only a few are implementing projects with public or foreign funding.

Where are the women?

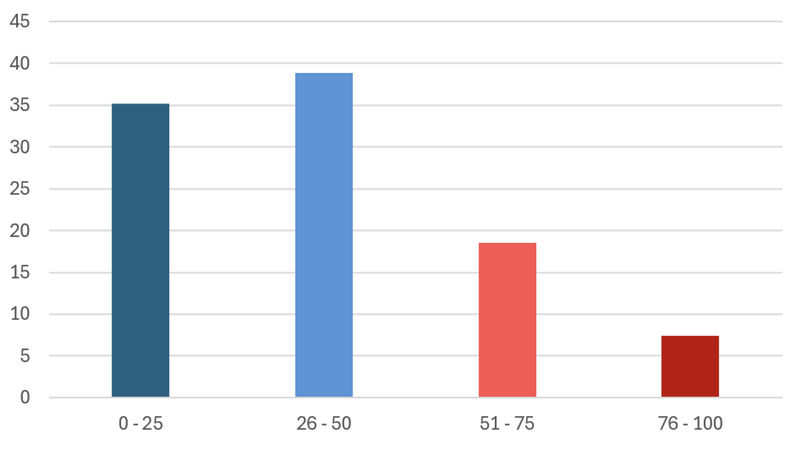

Figure 4: Gender Distribution

Most of the organisations have more men than women as members. Almost three-quarters (74%) of the organisations are predominated by men (dark and light blue columns combined). In 35% of the organisations (dark blue) the women are fewer than 25%). Only 26% of the organisations have more women members than men (pink and dark red columns combined). 19% of the organisations have 51-75% women members (pink column), and only 7% of the organisations can be dubbed as ‘women organisations’, i.e., organisations with more than 75% women members (dark red column).

This gender composition is not surprising, given the traditional culture and patriarchal family structures prevailing in Angola. Girls and women are traditionally considered responsible for domestic chores and their economic activities are generally supporting the family through tilling the fields, fetching water and firewood, and looking after the children and the elderly.

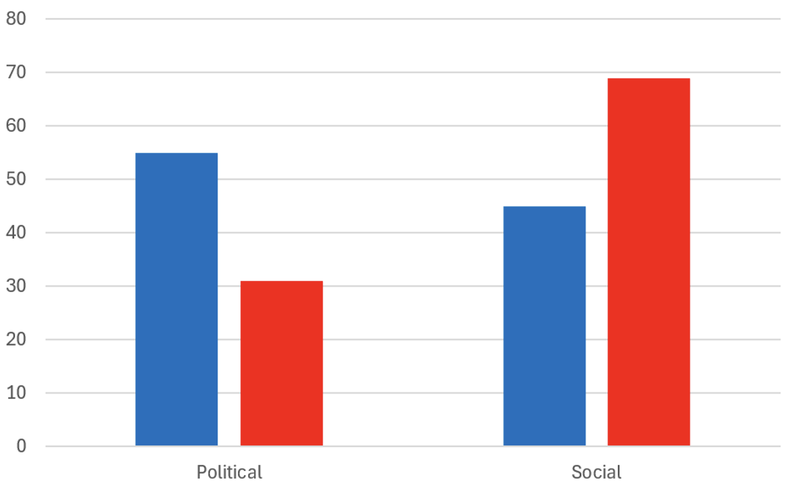

Figure 5: Gender and Focus

When looking at the gender distribution in political versus social organisations, it is evident that women are more engaged in what is classified as ‘social’ organisations, and much less so in organisations and movements with a political profile. The graph depicts organisations and movements predominated by men (blue columns: 0-50% women members) and those predominated by women (red columns: 51-100% women members), respectively for organisations and movements with a political profile versus those with social and economic development as their focus. Political issues are the focus of only 31% of the organisations predominated by women.

This thematic orientation is also not surprising given the prevailing traditional gender roles whereby ‘politics’ is the exclusive preserve of ‘politicians’. It is not considered appropriate for ordinary citizens – let alone women – to speak out publicly on political issues.

According to some of the respondents, conformity to predominant social norms has proved to be the easiest path to privilege and prestige. Dissent, on the other hand, brings adverse consequences and personal costs. Women, when they are mothers and heads of household, they ‘protect’ their children and themselves from the possible negative effects of dissent.

What are their opinions?

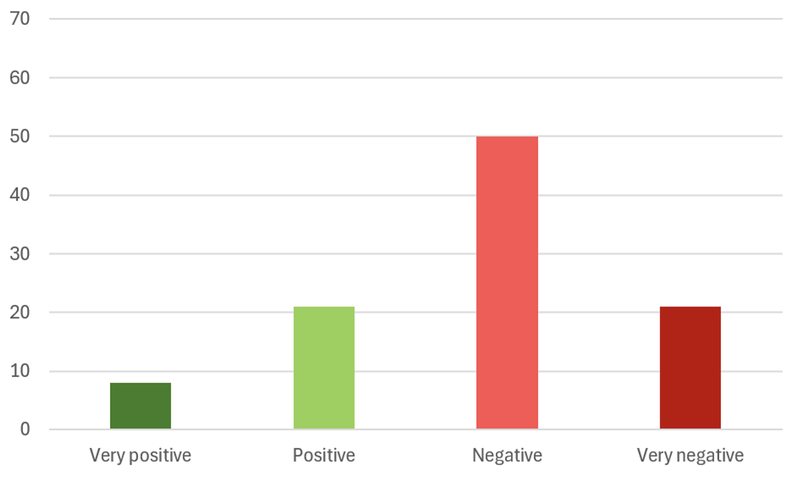

Figure 6: Opinions on Government

What are their opinions on the government? The survey respondents expressed a very negative view of the government. This was evident in their opinions on several questions, e.g. on positive or negative perceptions on the government’s democratic posture, transparency, legal framework, and respect for human rights. The overall opinions were negative (red columns combined, 71%), versus a 29% positive government rating (green columns). Furthermore, only 8% were very positive, in contrast to 21% being very negative.

These findings are hardly surprising given the Angolan government’s democratic shortcomings according to Amnesty International’s latest overview (AI 2025): “Civil society activists and journalists were arrested and detained for exercising their rights to freedom of expression and peaceful assembly”. Human Rights Watch (HRW 2025) expressed similar views: “Despite the President João Lourenço’s pledges to protect human rights, Angolan security forces continued to use excessive force against political activists and peaceful protesters. The government introduced new laws that would allow excessive control over private institutions and undermine rights to freedom of expression and association and media freedom.”

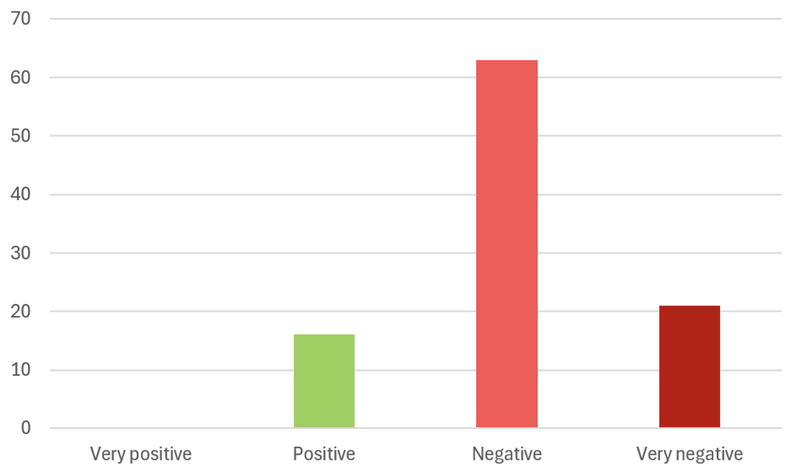

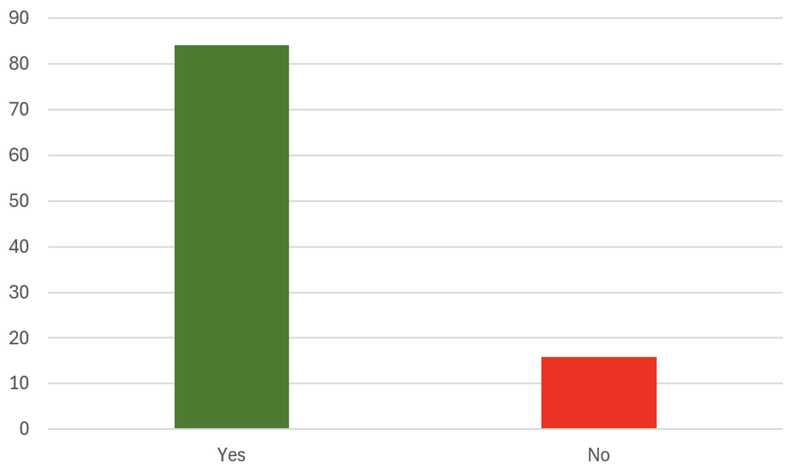

Figure 7: Opinions on Government – Civil Society Relations

What are their opinions on the relationship between government and civil society? On this question, the perception was even more negative than the perception of the government in general. The majority of 84% was very negative – 21% very negative and 63% negative (pink and red columns). Only 16% was positive (green column), and no respondent in our sample considered the relationship between the government and civil society as very positive.

Most of our respondents considered that “the relationship between the civil society and the government is bad, very bad. The government does not consult civil society and movements, discourages participation and instigates violence during demonstrations”. Some said that “the government only consults civil society and movements when it is interested”. However, a few (13%) had a better experience and said that “the government recognises civil society as important interlocutors and consults regularly”.

On the specific question of how the survey respondents perceived parliament (National Assembly), and whether they found that parliament “values civil society contributions”, the perception was also clearly negative. Almost three-quarters (75%) did not see that parliament valued civil society contributions as positive and another 4% was very negative to the idea (which adds up to a negative rate of almost 80%). Only 21% considered that the National Assembly values the contributions of civil society (but no respondent considered it clearly positive). The reasons they gave was that “The National Assembly has never consulted civil society or welcomed their contributions”.

Likewise, on the question of the government’s respect for human rights, only 17% of the respondents gave an affirmative response. By contrast, 50% did not think so, and another 32% strongly denied that the government respected human rights. The provided an extensive list of examples of disrespect for human rights, including the lack of respect for the freedom of speech, of media bias (government propaganda and censorship), as well as assaults, intimidation, house demolitions, and extrajudicial killings.

On the question of how they would characterise the legal framework for civil society to operate, the majority held again a negative opinion (33%) or a very negative opinion (30%). Even so, 35% had a positive view, and 3% were very positive. The respondents cited restrictions on access to information, of assembly and demonstrations, as well as administrative hurdles in the legalisation of organisations.

It is important to note that during the preparation of the survey, the government had launched a package of legislative measures that would have negative impact on civil society (see Gomes et al. 2023).

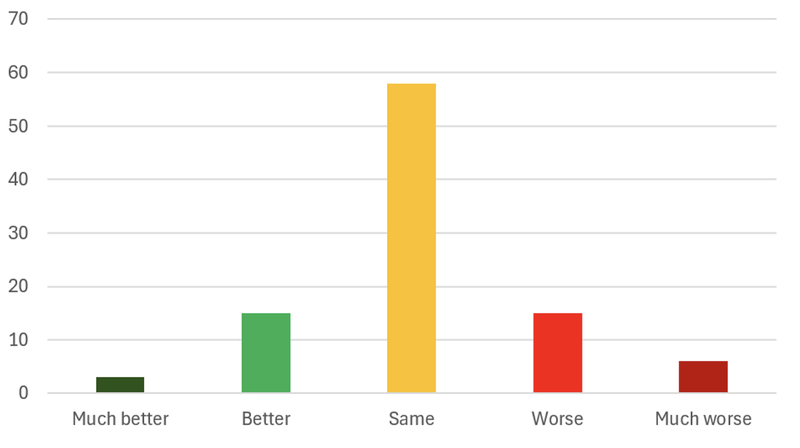

Figure 8: Better Now?

Has the situation improved under President Lourenço? On the question on whether the current presidency/government of Lourenço is different from that of his predecessor, one-fifth considered it to be better (green columns - 15% better and 3% much better), and one-fifth considered the new administration to be worse previous (red columns - 15% worse and 6% much worse). The large majority (58%) held the opinion that the differences were minimal.

What are the strategies?

Given the persistently adverse conditions for civil society in Angola, the respondents to our survey, interviewees, and participants in the regional meetings suggested some coping strategies.

Figure 9: Collaboration

One strategy is to ensure that most organisations become members of a larger civil society collective or platform. In other words, most organisations (84%) subscribe to this strategy by collaborating with other civil society organisations in an alliance or network, on a platform or other form of formal co-operation within Angola. Only 16% did not. Most collaboration (almost 60%) takes place at the local level, in municipalities, communes, and neighbourhoods, and about 35% at the regional and national levels. However, very few (only 1.5%) reported links with international partners.

International partners are probably hampered by language barriers and financial constraints. Moreover, cooperation with international NGOs is viewed with suspicion by the government, at least regarding political issues.

Alignments with local partners, on the other hand, is a strategy for gaining and increasing social capital. Proximity and local roots generate trust, rendering collaboration and networking easier. There is empowerment in local partnerships.

At the same time, the respondents reported that beyond partnerships at the local level, partners at the national level carried the greatest weight. The reason is that partners in Luanda have more resources, give better access to information and closer proximity to centres of power.

An alternative strategy is the formation of looser social movements of an informal nature rather than more tight-knit organisations. In our survey, around 14% of the respondents identified themselves as belonging to (and answering on behalf of) ‘social movements’.

The respondents had noted the legal restrictions on civil society and NGOs, as well as the administrative hurdles in the legalisation of organisations. Social movements are reportedly a survival strategy. The study did not provide time-series data to confirm our impression that at least some social movements are formed instead of organisations to avoid hassles and risk, as well as for gaining flexibility. Movements understand themselves as more loosely organised, are not seeking official recognition as formal organisations, and are more often focussed on one issue at a specific time and place – formed ad-hoc in response to concrete contexts of deprivation, injustices, and denial of rights (at the same time as they face a risk of becoming personalised, furthering self-interest, and being co-opted by stronger forces).

What do they want?

Through the regional and national meetings and debates with the survey respondents and other representatives of the organisations, we were presented a proposal for a common agenda for civil society organisations and social movements in Angola.

Regardless of their specific agendas, the participants presented a long list of proposals and a main priority: to defend democracy and the rule of law. They wanted to work for human rights, respect for the separation of powers, the de-politicisation of the institutions of government, as well as the independent monitoring of elections and oversight of the extractive industries. Furthermore, they expressed a wish for a national network to protect human rights activists, a funding mechanism for civil society, and increased national and international networking.

References

AI (2025): Angola 2024. Chapter in Amnesty International Report 2024/25 (Human rights in Angola Amnesty International).

Amundsen, Inge and Cesaltina Abreu (2006): Civil Society in Angola: Inroads, Space and Accountability. Bergen, Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI), CMI Report R 2006: 14 (Civil Society in Angola: Inroads, Space and Accountability).

Gomes, Catarina Antunes, Cesaltina Abreu, Margareth Nangacovie and Inge Amundsen (2023): Subverting the Constitution and Curtailing Civil Society. Angola’s New Law on NGOs. Bergen, Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI), CMI Insight 2023:2 (Subverting the Constitution and Curtailing Civil Society. Angola’s New Law on NGOs).

HRW (2024): Angola: President Signs Laws Curtailing Speech, Association. Human Rights Watch (HRW) news, Johannesburg, 10 September 2024 (Angola: President Signs Laws Curtailing Speech, Association | Human Rights Watch).

HRW (2025): Angola. Country Page, online, Human Rights Watch (HRW) (Angola | Country Page | World | Human Rights Watch).

Statista (2025): Population of Angola in 2022, by province (Angola: population by province 2022| Statista).