Local Content in Tanzania’s Gas and Minerals Sectors: Who regulates?

A Confusing Array of Regulatory Agencies

Making Policies in a Situation of Overlapping Authority

Impact on Training and Skills Development

Impact on the Development of Small and Medium Enterprises

Impact on the Monitoring and Enforcement of Local Content Regulations

How to cite this publication:

Jesse Salah Ovadia (2017). Local Content in Tanzania’s Gas and Minerals Sectors: Who regulates? Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI Brief 6)

The implementation of Tanzania’s local content policy for the petroleum and mineral sectors has been hampered by inconsistency, confusion, and un-coordinated donor interventions. There is a need to replace overlapping institutional authorities by clear lines of regulatory authority to advance Tanzania’s vision of leveraging its gas and mineral wealth for industrial transformation. This is crucial in the areas of training and skills development, the development of small and medium enterprises, and the monitoring and enforcement of regulations.

A Confusing Array of Regulatory Agencies

In previous eras, Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) was seen as an end in itself, rather than a means for promoting economic development. However, FDI does not always produce more positive outcomes than negative ones. In fact, the examples of Angola and Nigeria, as well as Tanzania’s own experience with its mining sector, show the difficulty of achieving development from natural resources alone. Since the mid-2000s African countries, including Angola and Nigeria, have put in place local content policies (LCPs) to maximize the benefits from resource extraction (Ovadia ; 2016a and 2016b).

Local content policies encourage local employment and the use of local goods and services in backward-linked supply chains of companies active in a given country. While LCPs can apply to both foreign and domestic companies, they often focus on FDIs to produce greater economic benefit through value addition. In Tanzania, as in much of Africa, these policies take the form of targets for local participation and various reporting mechanisms. A more expansive definition would also include economic empowerment as part of local content. In whatever form, LCPs require capable and effective institutional oversight on the part of government. The importance of strategic direction from an autonomous and empowered government institution is illustrated by the experiences of state-led development in East Asia.

In early July 2017, the Parliament of Tanzania, under a certificate of urgency, passed three new acts on natural resource management. The new acts were first tabled for comment on 29 June 2017 and were approved by the National Assembly the following week. The new acts are: (1) The Natural Wealth and Resources Contracts (Review and Re-negotiation of Unconscionable Terms) Act (the Unconscionable Terms Act); (2) the Natural Wealth and Resources (Permanent Sovereignty) Act; and (3) the Written Laws (Miscellaneous Amendments) Act (Miscellaneous Amendments Act). These acts will implement a host of changes to the legal regime underpinning the management of Tanzania’s natural resources, both in the mining industry and the oil and gas sector. The new legislation is likely to have a far-reaching impact on contractual arrangements in the extractive sectors. Companies must satisfy further provisions on local content, corporate social responsibility (CSR) and the requirement for mineral rights holders to make an integrity pledge. The acts can be downloaded from the Parliament’s website: http://www.parliament.go.tz/

Although Tanzania has taken many positive steps in directing and overseeing resource extraction, there are at least nine government agencies and parastatals with direct regulatory authority over some aspect of petroleum and solid mining, along with a variety of secondary regulators and more peripheral agencies. At the centre is the Ministry of Energy and Minerals (MEM) with commissioners directly under the Minister. Other ministries, such as the Ministry of Home Affairs, have direct regulatory authority over some related areas, such as immigration.

On the mining side, the Mining Commissioner retains regulatory authority, but is assisted by the Tanzania Minerals Audit Agency (TMAA). TMAA carries out audits but has no authority to intervene directly should it uncover any financial irregularities. It has no official role regarding local content, but has nevertheless taken the lead in publishing applied policy research on local content in mining. The state mining company, STAMICO, has little direct involvement in local content, though it holds the state’s interest in some of the country’s biggest mines. STAMICO is not heavily involved in designing LCPs, nor has it instituted many policies to encourage local participation in its own mines.

On the petroleum side of MEM, the Commissioner seems to have less authority over the sector, particularly with the passage of the Petroleum Act of 2015, which created a new Petroleum Upstream Regulatory Authority (PURA). This agency is still being established and is staffed by employees of MEM and the state oil company, Tanzania Petroleum Development Corporation (TPDC). TPDC plays a more direct role in drafting and implementing oil and gas policy than STAMICO does in mining. Midstream and downstream oil and gas regulation is the responsibility of another agency, the Energy and Water Utilities Regulatory Authority (EWURA).

Which of these agencies has the power to regulate the oil and gas industry, and how they share authority over local content policy is not clear. To complicate matters further, in an October 2015 meeting of the Tanzania National Business Council (TNBC), then President Jakaya Kikwete provided another agency, the National Economic Empowerment Council (NEEC), with a mandate to coordinate the government’s local content policy. NEEC, which is under the Prime Minister’s Office, set up a Local Content Department to take the lead on local content issues and has appointed focal points within each ministry and parastatal to coordinate local content promotion.

Making Policies in a Situation of Overlapping Authority

Overlaps and lack of clarity have made it challenging for these various agencies to work together. In the case of Tanzania’s emerging gas sector, TPDC, MEM, PURA, and EWURA must work with the Prime Minister’s Office and NEEC, TNBC, the Office of the President Oil and Gas Advisory Bureau and the Uongozi Institute. The latter is a research, training and capacity building organization that is officially a part of the government and has been involved in research and training for government officials on various aspects of petroleum and minerals policy, including local content.

The regulatory framework for public procurement is established in the Public Procurement Act (2011) and overseen by the Public Procurement Regulatory Authority (PPRA). This Act makes it easier for Tanzanian companies to compete for government contracts, including from parastatals such as TPDC and STAMICO. In some cases, these two parastatals’ procurement policies may be more detailed than the Act while in others they may contradict it. In theory, the Act should also apply to most major natural gas and mining projects, though in practice it is not clear if it does or how well TPDC and STAMICO have adhered to the law.

Coordinating Tanzanian participation in the gas and mining sectors requires a focus on the education, training and vocational skills that employers require in these industries and their backwardly-linked suppliers. While NEEC plays an important role in this respect, its role overlaps with the above-mentioned agencies. At the same time, the Ministry of Education and the Vocational Education and Training Authority (VETA) are involved in training and skills development for the extractive industries.

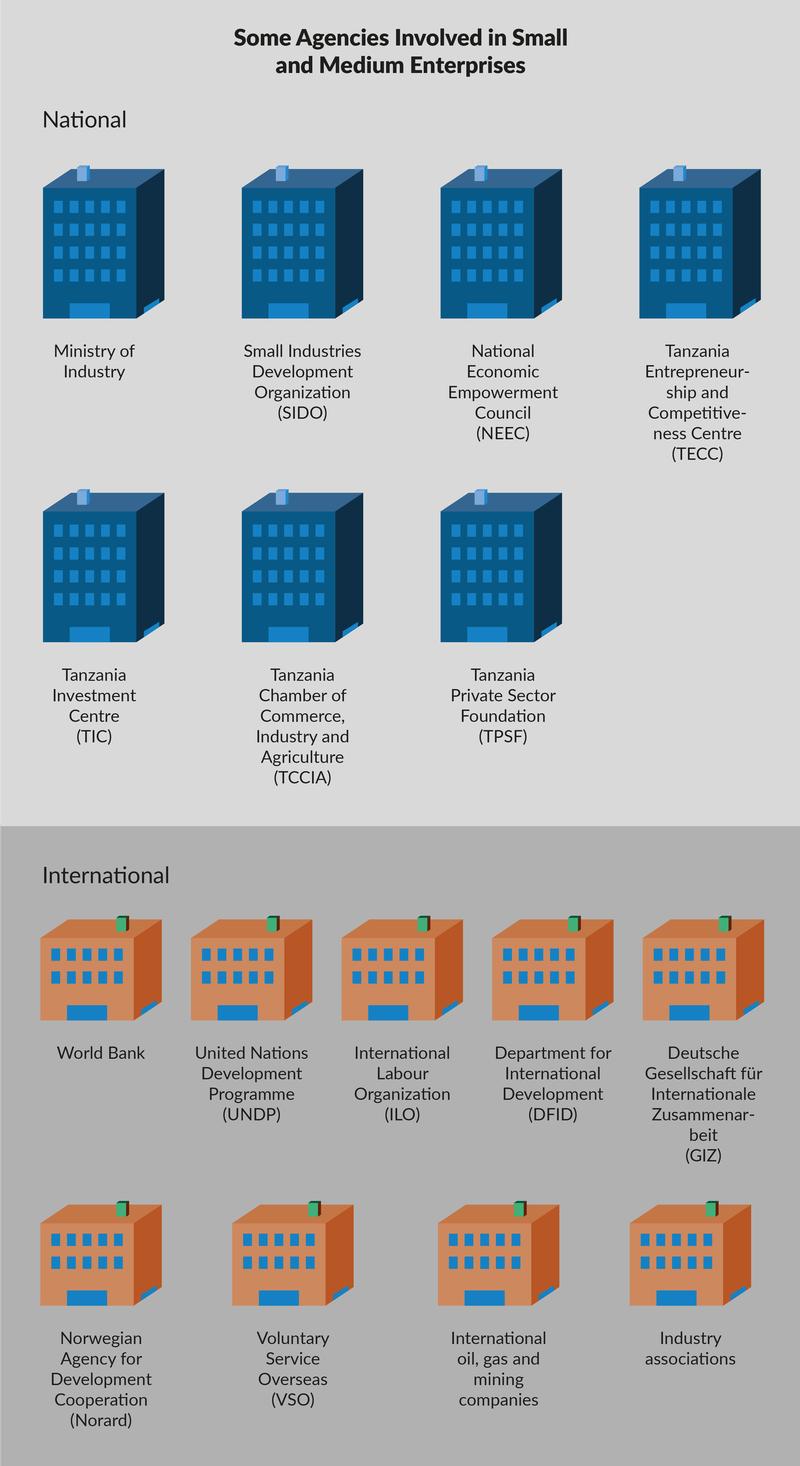

Extensive institutional overlap occurs in the development of small and medium enterprises (SMEs). As international oil and mining companies adjust their procurement policies to buy more from local companies, the government also aims to support the development of SMEs as part of its overall local content strategy. NEEC has several programmes related to SME development, even though this is officially part of the Small Industries Development Organization (SIDO), an agency under the Ministry of Industry. Additionally, TNBC, Tanzania Entrepreneurship and Competitiveness Centre (TECC), and the Tanzanian Investment Centre (TIC) also play supporting roles, as does the Ministry of Health, Community Development, Gender, Elders and Children.

Impact on Training and Skills Development

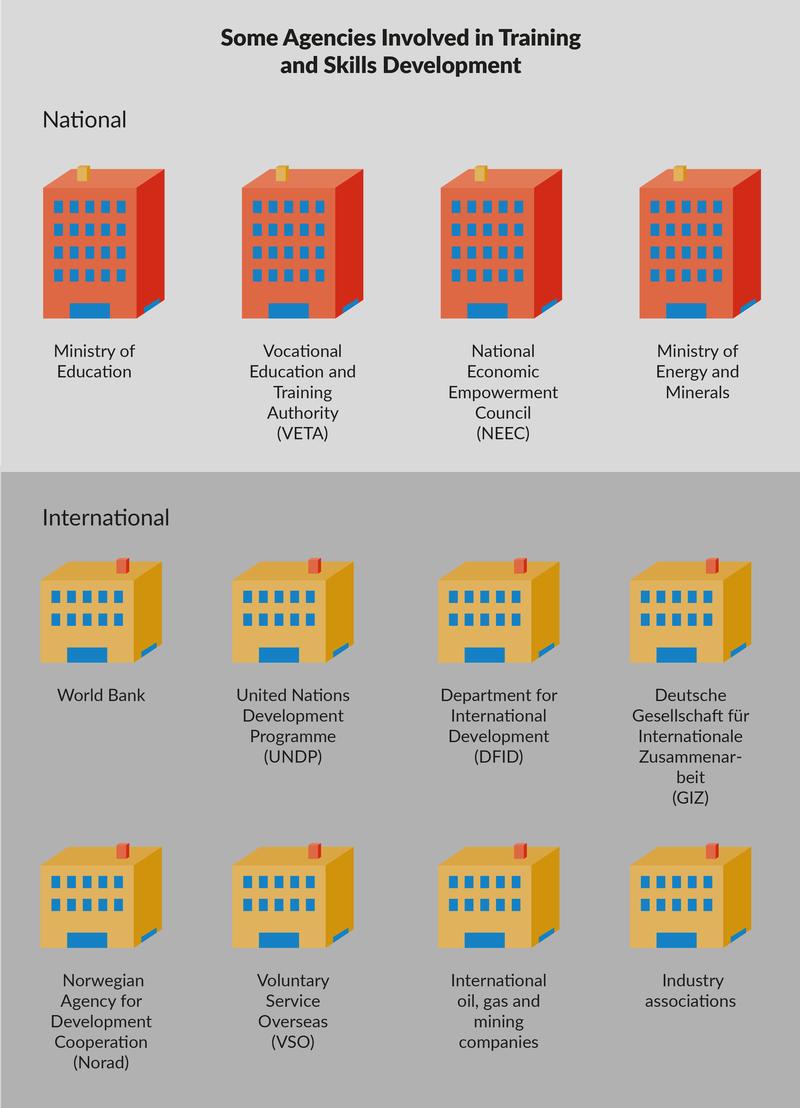

When it comes to training and skills development, there is a whole set of government agencies that have overlapping authority. There are also numerous national and international organisations working on similar projects with similar goals.

The Ministry of Education plays a central role in training and skills through the primary and secondary school system, higher education, and vocational training. VETA coordinates, regulates, and provides vocational education and training. NEEC operates separately from the Ministry, although with a high level of coordination in the emerging natural gas regions of Lindi and Mtwara. MEM also has several projects related to skills development in these regions.

A number of development organisations such as the World Bank, UNDP, DFID, GIZ, Norad, VSO and others work on training and skills development, often in partnership with NEEC and/or VETA. These organizations also collaborate with the major international oil, gas and mining companies to align training with the needs of the extractive industries.

While there are some excellent initiatives making impressive contributions to the country’s development, there is also a lot of project overlap—especially with so many initiatives focused on Lindi and Mtwara. In the case of training and skills development, the projects are different enough, the need is great enough, and government authority is sufficiently clear that the negative impacts of overlapping agencies and projects is minimal.

Impact on the Development of Small and Medium Enterprises

In the area of SME development, a large number of government agencies have overlapping authority and a similar set of international organisations carry out overlapping initiatives. The large number of agencies with overlapping mandates is made worse by the lack of direction from SIDO, which would seem to have the clearest authority in this area. The lack of leadership opens the door for NEEC, TECC and others to get involved.

Non-governmental organisations and private sector interest groups are also active in promoting SME development. The Tanzania Chamber of Commerce Industry and Agriculture (TCCIA) and the Tanzania Private Sector Foundation (TPSF) both appearing to serve largely the same purpose, are both active in SME development. TNBC provides oversight in parallel to SIDO and others.

The same international institutions and international oil, gas and mining companies sponsor initiatives related to SMEs. However, in this case there is more direct institutional and project overlap and seemingly less coordination than with training and skills development. The Tanzanian financial sector is also involved, especially on the question of access to finance. Perhaps as a result of all of this overlap, SMEs may not know where to go for support while international investors may have difficulty identifying local companies that could be partners or suppliers. As key initiatives such as business support/enterprise development centres are contemplated by multiple donors and government agencies, the risk is that competing centres will be set up, further complicating the drive to increase the participation of local companies in the extractive industries.

Impact on the Monitoring and Enforcement of Local Content Regulations

With so much overlapping authority regarding implementation of LCPs, it is unsurprising that the draft local content regulations required under the Petroleum Act and currently under consideration by MEM leave many questions unresolved.

Amongst the different agencies, there are different approaches to local content and even definitions of what local content means. This has led to confusion and inconsistency between different official policies, legislation, and regulations in terms of what local content is and what constitutes a local company. Various agencies are navigating issues of overlapping authority as they arise instead of taking an integrated approach to maximizing local content. The same is occurring with regard to the question of who regulates midstream petroleum projects (such as the proposed liquid natural gas processing facility), as well as with the question of what mandatory targets for local participation should be set and in which areas.

It seems likely that some agencies will be left out of the process of monitoring and enforcing LCPs—in all likelihood agencies such as NEEC and TMAA that have been the most proactive. Lacking an official role in monitoring and enforcement may also make it difficult for these agencies and others, such as SIDO and VETA, to implement projects that fall more clearly within their mandates. Examples of such initiatives include the work TMAA has done to publish data on local content in the minerals sector or NEEC’s empowerment initiatives for small businesses—especially those involving women and youth. In other cases, without a single government authority, it may be more likely that international donor agencies and private firms will design and implement projects targeting training, skills development, and SMEs without input or coordination from the government.

Finally, overlapping authority may make it more difficult to use the proper fiscal incentives or to align policy in areas as diverse as special economic zones, immigration, foreign investment, public procurement, education, financial services, standards, and more with the overall local content strategy.

Policy implications

Training and skills development, small and medium enterprises, and monitoring and enforcement of regulations are three key areas for public sector intervention. In order to address overlapping authority, there is a need for clarity on LCPs, related policy areas, and institutions and structures for government oversight.

First, education, training, skills, and SME development are not always understood in Tanzania as key elements of LCPs in petroleum and mining. A stronger understanding of this along with clarifying and streamlining authority in all of these areas would allow Tanzania to maximize the benefit of local content.

Second, a continued effort by the various agencies for mutual coordination as well as coordination with international companies, civil society organizations, the media, labour unions and affected communities will ensure transparency and accountability in local content implementation.

Recommended Reading

Lange, S. and Kinyondo, A. (2016). Local Content in Tanzania’s Mining Sector. The Extractive Industries and Society, 3(4): 1095-1104.

Ovadia, J. S. (2016a). Local Content Policies and Petro-Development in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Comparative Analysis. Resources Policy, 49: 20-30.

Ovadia, J. S. (2016b). The Petro-Developmental State in Africa: Making Oil Work in Angola, Nigeria and the Gulf of Guinea. London: Hurst & Co.

Ovadia, J. S. (forthcoming). Local Content Situational Analysis in Tanzania in the Mining and Gas Sectors. Abidjan: African Development Bank (In Press).

Shangvhi, I.S. (2016). Effective Management of the Tanzanian Natural Gas Industry for an Inclusive and Sustainable Socio-Economic Impact: A Baseline Study. Dar es Salaam: Economic and Social Research Foundation and The African Capacity Building Foundation.

This Brief is an output from Tanzania as a future petrostate: Prospects and challenges, a five-year (2014–2019) institutional collaborative programme for research, capacity building, and policy dialogue. It is jointly implemented by REPOA and CMI, in collaboration with the National Bureau of Statistics. The programme is funded by the Norwegian Embassy, Dar es Salaam. The author would like to thank Kendra Dupuy, Odd-Helge Fjeldstad, Ingvild Hestad and Jan Isaksen for comments and insights. Views and conclusions expressed within this brief are those of the author.