Petroleum populism: How new resource endowments shape voter choices

The political pitfalls of petro-promises

The voters’ verdict: Popular exaggerations and the need for a clean slate

How to cite this publication:

Andreas Stølan, Benjamin Engebretsen, Lars Ivar Oppedal Berge, Vincent Somville, Cornel Jahari, Kendra Dupuy (2017). Petroleum populism: How new resource endowments shape voter choices. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI Brief 2017:11)

High-value natural resources can be a political “curse” when political elites use resource revenues to maintain power, subvert democratic rule, and distribute public goods to their supporters. New resource discoveries can also shape citizens’ political behaviour in negative ways, for instance by encouraging voters to elect politicians who make overly ambitious promises about future resource revenues. Evidence from a recent survey experiment in Tanzania shows that new petroleum reserves can negatively impact voter behaviour. To prevent opportunistic candidates from coming to power and poorly managing the country’s new wealth, voters need improved access to information about the development of these resources.

The political pitfalls of petro-promises

New oil and gas discoveries hold great economic promise for citizens of low-income countries, offering a prospect for poverty alleviation. But if citizens are to benefit, these resources must be well managed by government. Political leadership is especially important in this resect, given that national-level political leaders create the legislative framework for governing petroleum resources and exert high levels of authority over them. A risk, however, is that the high value of petroleum will attract self-interested politicians to serve in government, rather than individuals who would use petroleum resources and revenues in ways that benefit the general public. To increase their chances of winning office in democratic elections, self-interested candidates may use opportunistic rhetoric about petroleum resources and over-sell what they can deliver from new reserves.

Through a survey experiment, we found evidence that voters are very responsive to exaggerated promises of short-term economic gain and prefer opportunistic candidates over pragmatic ones. Instead of choosing leaders who will wisely manage a country’s oil and gas reserves, voters are likely to select candidates who will ultimately undermine citizens’ long-term interests.

“Voters are likely to support politicians that make exaggerated promises about future petroleum revenues”

Several studies have shown that petroleum resources can negatively influence the democratic process and quality of government. Oil windfalls make it more likely for incumbent politicians to be re-elected, resulting in less competitive elections (Ross 2015; Goldberg, Wibbels, and Mvukiyehe 2008). In Brazil and India, oil windfalls have attracted individuals with criminal backgrounds and lower education levels to run for office (Brollo et al 2013; Asher and Novosad 2014). Expectations of future natural resource booms in São Tomé e Principe and in Madagascar in the late 1990s and early 2000s led to high levels of corruption in the resource sectors of both countries, plus a shift in each government’s allocation of public resources to favor private interests, the creation of institutional overlap and competition, and vote-buying (Frynas, Wood, and Hinks 2017).

Opportunistic rhetoric about future petroleum revenues is designed to raise hopes and expectations about what will occur in the future. As Cust and Mihalyi (2017) write, despite the fact that a petroleum discovery will not be realized for many years, “it can be considered a step-change in known national wealth, implying increased economic output in the future and a permanent increase in consumption potential for the country. A discovery can therefore generate expectations of increased economic activity and consumption in the future” (p. 3). Politicians can promise the moon and win office without ever having to deliver, since voters may not remember these promises or politicians may have long since left office by the time petroleum is actually extracted.

A discrete choice experiment

To find out how and whether voters respond to opportunistic, populist rhetoric about new offshore petroleum reserves, we embedded an experiment within a large household survey in three regions of Tanzania: Dar es Salaam, Mtwara, and Lindi. Dar es Salaam is the country’s largest city, and hosts around ten percent of the population and most of the economic activity. In contrast, Lindi and Mtwara are two of the poorest regions, with low levels of economically productive activity, but are where recent important offshore petroleum discoveries have been made.

In the experiment, 2818 participants were asked to choose multiple times between two hypothetical presidential candidates. By varying the characteristics, or attributes, of the candidates between each choice task, we were able to uncover the respondents’ preferences for individual attributes (for example, if they prefer male over female candidates) as well as to tease out the weight that the respondents placed on each of the respective attributes relative to the others (for example, if gender is more important than religion). In short, the experiment allows researchers to establish which attributes they assign the most weight to when making their choices.

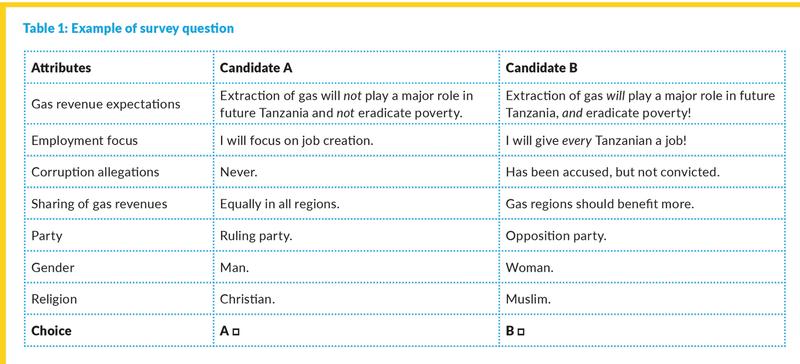

The experiment included hypothetical candidates who 1) made exaggerated promises regarding the potential of future petroleum revenues; 2) had been accused of corruption in the past; and 3) stated different preferences for how to distribute the potential future petroleum revenues. Table 1 shows the attribute choices that respondents were asked to select between in the experiment.

The voters’ verdict: Popular exaggerations and the need for a clean slate

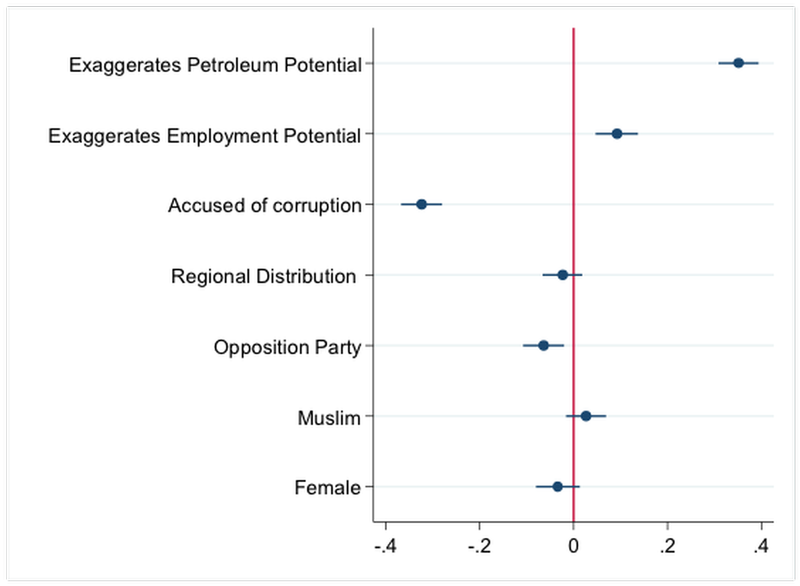

Three main results came out of the experiment. First, as seen in the first line of Figure 1, participants were likely to reward candidates that made exaggerated statements about the potential impact of the petroleum discoveries. Voters with high levels of trust in the authorities and high expectations for their financial future were even more inclined to reward exaggerated petroleum-related rhetoric (not shown in the figure).

Second, participants were likely to punish candidates accused of corruption, as seen in the third line of Figure 1. Thus, while voters may respond favourably to hyped-up, unrealistic rhetoric about the future benefits of new petroleum resources, they are unlikely to vote for candidates who lack a reputation for being a trustworthy steward of those resources.

Regression coefficient plot. Coefficients that fall on the red line are not statistically significant. Significant coefficients that fall to the left of the red line mean that voters punish a candidate for that attribute at the ballot box, while significant coefficients that fall to the right of the red line mean that voters reward a candidate for that attribute (voting for the candidate).

Third, residents of resource-producing regions are likely to prefer candidates that promise them resource revenue redistribution (also not shown). Participants in Dar es Salaam preferred a national distribution policy, while Mtwara residents preferred a distribution that would benefit them alone. Interestingly, participants from the other petroleum-rich region, Lindi, had no strong preference about a revenue distribution policy. This finding can be explained by the very low level of information that the Lindi-based participants reported having about the gas reserves in their area.

A need for public information

While the discrete choice experiment was not an actual election, the results clearly indicate that large political benefits can be reaped for those who are willing to stretch the truth about the potential impact of petroleum discoveries. The use of opportunistic rhetoric can have serious consequences, as seen in the example of the deadly riots that occurred in Mtwara in May 2013 over the government’s decision to transport the gas in a pipeline to Dar es Salaam and not to refine and use it locally. The former president Jakaya Kikwete had promised Mtwara residents in his 2010 election campaign that “Mtwara will be the new Dubai”.

Public information is needed to help to prevent politicians from using opportunistic rhetoric, for three reasons. First, a general lack of information about petroleum reserves and future revenues increases the room for bending the truth in one’s own favor. Previous surveys of the Tanzanian population on knowledge levels about the country’s petroleum resources show a generally low level of awareness, enabling politicians to make exaggerated promises in order to gain popularity. Providing accurate information can help to ensure that voters select politicians who make realistic promises.

In a survey conducted in 2015 by Twawesa, a Tanzanian non-profit organization, 53% of the respondents believed that natural gas and revenues are already flowing. 75% of the respondents had not heard about the newly developed Natural Gas and Local Content policies (which determine distribution of petroleum benefits) or the Tanzanian Petroleum Development Corporation (the national oil company which owns all the licenses for energy development in the country). 77% of respondents believed that someone should provide them with more information about the gas discoveries in general, and 85% wanted specific knowledge about contracts made between foreign investors and the government. (Twawesa 2015)

Second, the likelihood of a person or political party using opportunistic rhetoric could be expected to increase if citizens have high trust in them and if the statements they make echo their hopes and desires. In our experiment, participants who reported high levels of trust in government were particularly likely to support candidates using populist petroleum rhetoric. Academic studies and opinion polls have reported that Tanzanian citizens are generally quite optimistic and have high levels of trust in government. Thus, it is even more important to provide accurate information about petroleum and candidate backgrounds to counterbalance opportunistic rhetoric and to prevent the election of corrupt or otherwise self-interested individuals.

Third, since the earliest estimate for the start of petroleum production is not until close to the year 2030, voters are unlikely to remember politicians’ present-day promises or politicians may even no longer be in office. Either way, it may be difficult for voters to hold politicians to account for their inaccurate and unmet promises. Information may therefore help to ensure that voters select candidates who are willing and likely to act in their best interest in the short- and long-term.

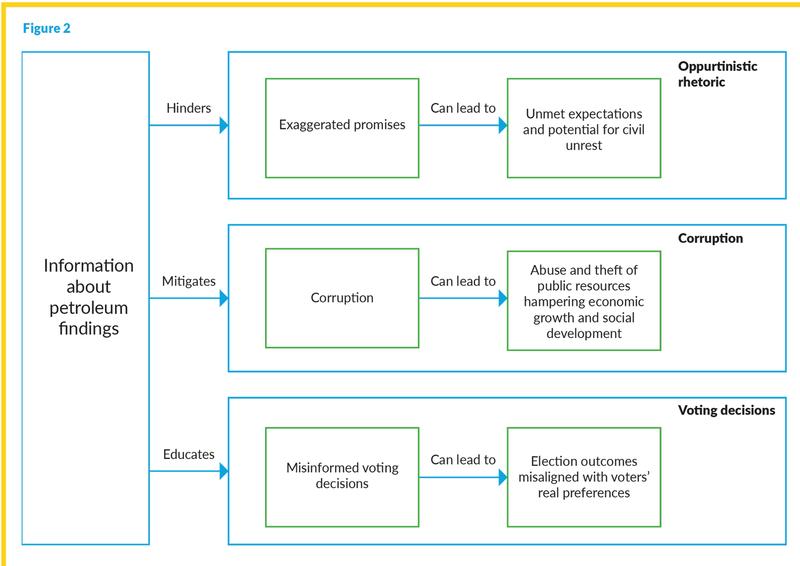

Figure 2 shows how information can help to create disincentives for making exaggerated promises, enable citizens to hold politicians more accountable, and help to safeguard against misinformed voting decisions.

References

Asher S., and Novosad P. (2014). Dirty politics: Natural resource wealth and politics in India. Unpublished manuscript. Accessed at http://www.nuffield.ox.ac.uk/users/Asher/research.html

Brollo, F., Nannicini, T., Perotti, R., Tabellini, G. (2013). The political resource curse. American Economic Review, 103(5): 1759–96.

Cust, J. and Mihalyi, D. (2017). Evidence for a presource curse? Oil discoveries, elevated expectations, and growth disappointments. Washington, D.C.: The World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 8140.

Frynas, J.G., Wood, G., and Hinks, T. (2017). The resource curse without natural resources: Expectations of resource booms and their impact. African Affairs, 116: 233-260.

Goldberg, E., Wibbels, E., and Mvukiyehe, E. (2008). Lessons from strange cases: Democracy, development, and the resource curse in the U.S. states. Comparative Political Studies, 41(4/5): 477-514.

Ross, M. L. (2015). What have we learned about the resource curse? Annual Review of Political Science, 18, 239–259.

Twawesa. (2015). Great expectations: Citizens’ views about the gas sector. Brief no. 25.