Family law reform in Sudan: A never ending story?

Family law reform in Northern Africa – Sudan the exception to the rule

Family law reform in Sudan: Stuck in a never ending law review

How to cite this publication:

Samia al-Nagar and Liv Tønnessen (2018). Family law reform in Sudan: A never ending story? Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI Brief 2018:08)

The family law in Sudan, legalises child marriage, stipulates a wife’s obedience to her husband, and gives the male guardian veto power on women’s consent to marriage. #JusticeforNoura has shone a spotlight on early and forced marriage as well as the continued legality of marital rape in Sudan. 19 year old Noura Hussein was sentenced to death for murdering the husband her relatives had forced her to marry after he raped her. It is urgent to reform the family law, and changes both within and outside the government suggest that now it can actually be possible. This brief outlines the history of the family law and offers clear recommendations to the Sudanese government.

This brief synthesises the CMI report Family Law Reform in Sudan: Competing claims for gender justice between sharia and women’s human rights. The analysis is based on long-term engagement and work on women’s rights and legal reform in Sudan. The article builds on extensive interviews, conducted in English and Arabic, between 2006 and 2017. We have interviewed reformists and conservatives within different government institutions, including the parliament, Ministry of Justice, Ministry of Social Welfare and the National Council for Child Welfare. We have also interviewed women’s right activists involved in initiatives for family law reform as well as various religious actors inside and outside of government institutions who have mobilized against legal reform.

Noura Hussein was betrothed to her much older cousin by her father at 15 without her consent. She ran away and stayed in hiding for three years, but her family tricked her into returning back home and married her off by force. After refusing to consummate the marriage for five days, she was raped by her husband with the assistance of his brother and a relative who pinned her to the bed. When he tried to rape her again the following night this time threatening her with a knife, she stabbed him to death. Because women, according to the 1991 Muslim Family Law, are obliged to obey their husbands, a wife cannot deny her husband sexual intercourse. The concept of marital rape does not exist. #JusticeforNoura has renewed demands for family law reform in Sudan.

What is Family law?

The Personal Status Law for Muslims came into being in 1991, following an intense period of Islamification led by the Sudanese government. It played a particularly important role in the Islamisation process led by the Islamist regime who came into power through a coup d’état in 1989.

The law has been described as a backlash against women’s rights activists and as a conservative and patriarchal interpretation of Sharia. The principal elements of the 1991 Personal Status Law for Muslims are marriage, maintenance, divorce, custody and inheritance. The law’s codification in 1991 is significant because it marks the transition of family law from the religious to the political field. Before 1991, family law was regulated through judicial circulars developed by the clergy. From 1991 onwards, family politics became an area of political contestation as the Islamist state, rather than the clergy became the principal authority. However, as the law is based on Sharia it is considered untouchable; therefore, reforms to the law have largely met resistance from religious conservatives.

Forced and early marriage

According to the 1991 law, the age of consent to marriage is tamyeez, that is, maturity understood as the age at which a minor has attained the ability to discriminate between right and wrong. A subsequent provision explicitly allows the guardian to contract a minor in marriage when there is overriding interest in doing so, and with the permission of a judge. Here, it does stipulate the specific age of 10, effectively making 10 the minimum age of marriage. Further, the 1991 law provides that a male guardian (wali) should only arrange the marriage of his ward with her consent. However, a subsequent section of the article on consent essentially gives the guardian the power to contract a marriage without the permission of his ward, so long as she consents later on. A contract concluded by the guardian before securing his ward’s consent may be termed voidable, but her refusal to consummate the marriage does not automatically void the contract. Rather, the woman must petition the court and prove that she did not consent to the marriage.

Obedience and marital rape

The overriding philosophy of the 1991 law is based on male guardianship, qawama in Arabic, where a husband is obliged to support his family financially (nafaqa) in exchange for his wives’ obedience. As a direct consequence of the stipulations on obedience (ta’a), the concept of marital rape does not exist within the law. An Islamist informant (Interview, 2009) explained the perspective as follows:

“Some consider it rape when a husband has sexual intercourse with his wife when she does not consent. In Islam we do not consider it as a rape. In Islam there is a contract between the man and the woman. To give adequate support [nafaqa] is obligatory for the husband. The other part of the contract is that a woman should obey. Therefore, a woman cannot refuse sex. It is obligatory for her”.

While Sudan reformed the rape article of its Criminal Code in 2015, it does not explicitly criminalize marital rape. Without a reform of the obedience clauses in the 1991 family law, the rape reform becomes void in cases of marital rape.

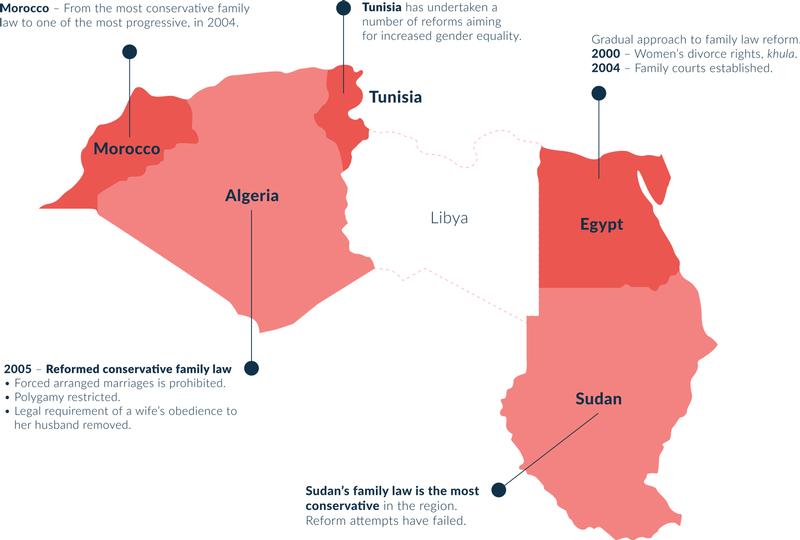

Family law reform in Northern Africa – Sudan the exception to the rule

Across Northern Africa, there have been a number of reforms in family law, despite opposition from religious conservatives. Some reforms have been minor, whereas others have been more comprehensive. Sudan stands out as the only northern African country that has yet to reform its family law to take into account changing global standards for women. Across the region, family law reforms have taken place in predominantly un-democratic settings and, perhaps with the exception of recent reforms in Tunisia, are closely associated with an authoritarian legacy. In Egypt, for example, reforms were closely tied to Mubarak’s authoritarian regime and therefore came under heavy pressure during the Arab Spring. However, they have not yet been repealed. Forwarding women’s equal rights has been a gateway to marginalize Islamic conservative groups as well as gaining international legitimacy.

Women’s rights activists have been instrumental in pushing for family reform across northern Africa. Along with using international and national legal frameworks to advocate reform, activists have used Islamic arguments to counter backlash from conservatives with varying degrees of success. Employing Islamic arguments becomes almost inevitable in contexts where family law is codified as religious law. Transnationally, one of the most important campaigns Musawah (‘equality’) advocates a feminist reading of Islamic scripture and argues that equality in family law in the Muslim world is necessary, and also possible without stepping outside the boundaries of religion. However, activists across the region selectively use existing and progressive interpretations of the Quran and lesser known hadiths, rather than create new feminist interpretations of the doctrine. For example, in Morocco the lesser-known hadith: “only an honourable person dignifies women, and only a wicked one degrades them” was used to support the 2004 mudawana reform efforts. It was presented as evidence that both spouses should be financially responsible for the family, not only the man.

Family law reform in Sudan: Stuck in a never ending law review

In present day Sudan, women’s rights activists are advocating for radical change, and for the eradication of male guardianship. All marriages should be based on consent and, according to activists, children cannot consent to marriage. It follows that women should be able to contract herself in marriage, not the male guardian. And once women enter marriage, they should consent, not engage in sexual acts because they are expected to obey their husband. Consent is paramount in Islam and without it a sexual act loses its legitimacy. According to activists, the ideology underpinning the 1991 law needs to radically change, as it relegates women to secondary citizenship.

Consent is paramount in Islam and without it a sexual act loses its legitimacy.

As of today, the only positive reform of family law in Sudan’s history was in 1969, under the rule of Jafaar Nimeiri, when the minister of justice abolished police enforcement of ‘house obedience’. Although an achievement at the time, it did not challenge the idea of a woman’s obedience to her husband. In today’s Sudan activists are demanding the obedience clauses to be abolished altogether.

Reform of the family law has been on the agenda of the women’s movement since the codification of the family law in 1991. There have been several stages in activism and mobilization for family law reform. In the early 1990s, when the Sudanese regime was at its most repressive, women’s rights groups and the Ahfad University for Women began concrete initiatives for family law reform. The group of female lawyers, Mutawinat, launched a review of the family law in 1997 where several demands for reform were presented. Up until the 2005 peace agreement, civil society led family reform efforts in Sudan.

Since 2005, and the signing of the Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) which ended the longest running civil war in Africa, family law reform have once again become a hot topic for women inside and outside of the government. Now also government reformist press for reforms such as establishing a minimum age of marriage at 18 and woman’s consent to marriage, meanwhile they largely stay loyal to the institution of male guardianship. However, the most major contribution came from women’s activists. In 2009, Sudan Organization for Research and Development launched an alternative family law.

During the last 8 years there have been an almost never ending stream of law reviews and recommendations, but these efforts have not culminated in any de facto reforms. Several and competing government committees have undertaken legal reform with varying degree of radical recommendations. Instead of using the alternative law as a common platform for mobilization, women activists are preoccupied with identifying its weaknesses, and yet again we see new initiatives for legal review of the 1991 law.

There is a consensus for raising the minimum age of marriage to 18 years, and for ensuring women’s consent in marriage. Yet, there has been little cooperation between women inside and outside the government in demanding reforms. The competition for recognition and for international funding have fractionalized mobilization for family law reform.

Family law has proved to be a particularly difficult area of law to reform in Sudan. As an Islam state, government has not been willing to violate the tenets of the religion in fear of upsetting religious conservatives inside and outside the state. For example, conservative religious actors continue to claim that puberty is considered the appropriate age of marriage. Supporters point to a hadith, in the Sahih al-Bukhari and Sahih Muslim collections, reporting the Prophet Muhammad’s betrothal to Aisha when she was six years old. However, evidence suggests that he did not consummate the marriage until she was at least nine years old and had reached puberty. Conservatives also claim that child marriage prevents illicit sexual relations. Sex before marriage is forbidden in Islam, and since “girls develop sexual urges” at puberty, it is said, early marriage is the Islamic solution to deal with the risk of fornication. Child marriage ensures that sexual relations happen only within marriage.

In the wake of Sudan’s 2016 Universal Periodic Review, there have yet again been rumblings of reform. The UN Human Rights Council recommended that Sudan raises the minimum age of marriage to 18 years. The Sudanese Minister of Foreign Affairs promised to execute this. Raising the minimum age of marriage is back on the negotiating table. The government has even engaged in discussions about signing CEDAW - one of the most sensitive and controversial topics in Sudan under the current government.

Conclusion - cautious progress

Change in Sudan still faces strong resistance, particularly from religious conservatives who continue to argue in favour of the status quo. However, there have been a number of positive developments that suggest that reform of the family law could be possible.

Women’s legal equality, in both public and private spheres, and hot topics, such as ratification of CEDAW, and ensuring a minimum age of marriage at 18 and women’s consent to marriage are being publically debated. It is notable that reformists within the Sudanese government have changed their position on women’s rights substantially in the past decade.

The collective mobilisation of women inside and outside the government will be key to reform success. They successfully worked together when they mobilised for a legislative gender quota, which suggests that they could manage the same for family law reform. In addition, women need to establish political alliances and strategies to combat religious resistance to reform inside and outside the government.

Recommendations

We strongly urge the Sudanese government to reform its 1991 family law. In particular there is an urgent need to

- Set the minimum age of marriage at 18

- Ensure women’s consent in marriage.

- Abolish stipulations on obedience which is key to protect women against marital rape.

We strongly encourage women inside and outside of the government to agree on a minimum agenda and work together to achieve much needed reforms within family law.

The ‘Women and Peacebuilding in Africa’ project looks at the cost of women’s exclusion and the possibilities for their inclusion in peace talks, peacebuilding, and politics in Somalia, Algeria, northern Nigeria, South Sudan, and Sudan. The project also examines the struggle for women’s rights legal reform and political representation as one important arena for stemming the tide of extremism related to violence in Africa.

The three themes that make up the project are:

- Inclusion and exclusion in postconflict governance

- Women activists’ informal peacebuilding strategies

- Women’s legal rights as a site of contestation

The ‘Women and Peacebuilding in Africa’ project is a consortium between Center for Research on Gender and Women at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI) and Isis-Women’s International Cross-Cultural Exchange (Isis-WICCE). The project is funded by the Carnegie Foundation and the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Liv Tønnessen