Turkey as a regional security actor in the Black Sea, the Mediterranean, and the Levant Region

Section I: Understanding Turkey’s Strategic Thinking

Strategic Geographical Position

Impact of International System

Ideational Inclinations of the Ruling Elite

Goals Hierarchy and Policy Drivers

Siege Mentality and the General Feeling of Insecurity

Maintaining/Increasing Capabilities through Development

Contemporary National Role Conceptions

Strategic Patterns of Behavior

Balancing (and Countering) Major Powers in International Relations

Attaining Regional Supremacy through Power Projection in Near Abroad

Section II: Balancing Actions in Turkish Foreign Policy

Balancing Between Russia and the West

Balance of Turkey’s Balancing Act: “Make Turkey Great Again”

Section III: Projecting Influence Beyond Borders: Capacity vs. Ambition

Leadership and Decision-Making Capacity

Strength of Alliance/Partnership Structures

Military Capacity as a Continuation of Politics

Intelligence: A New Dimension in Foreign Policy

Stability, Security and Recovery Programs

How to cite this publication:

Siri Neset, Mustafa Aydin, Evren Balta, Kaan Kutlu Ataç, Hasret Dikici Bilgin, Arne Strand (2021). Turkey as a regional security actor in the Black Sea, the Mediterranean, and the Levant Region. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI Report R 2021:2)

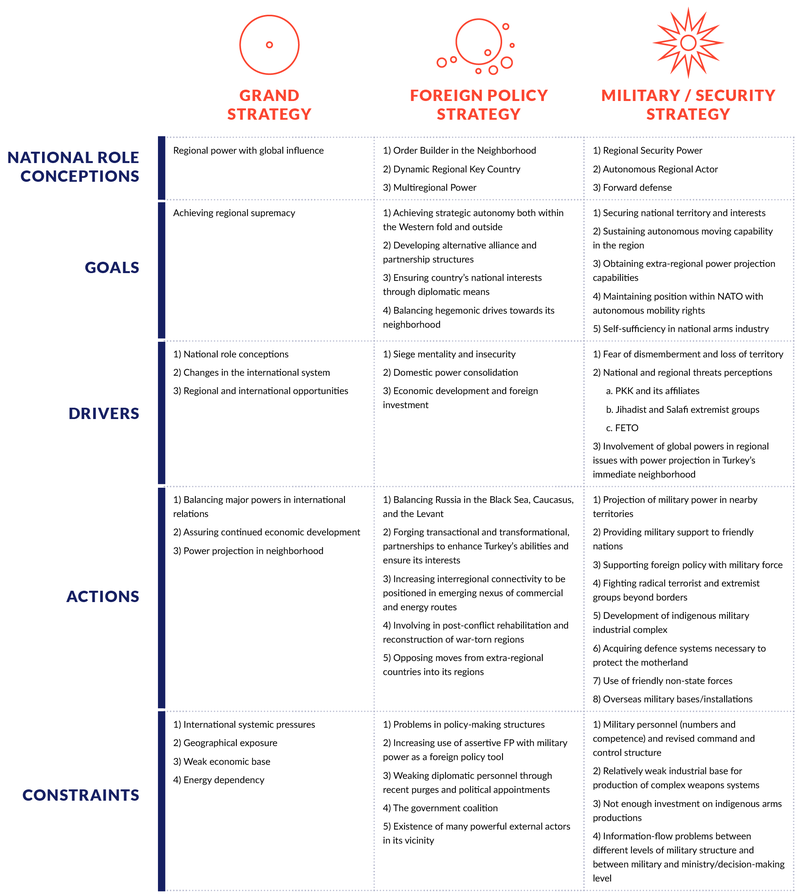

This report analyzes Turkey’s current foreign policy and its pronounced role as a regional security actor. It pinpoints deeper determinants and limitations of the policies that can be observed in different theatres of involvement. It identifies perceptions of policy makers and their political allies about Turkey’s needs, goals, limitations, and national role conceptions as well as what drives decision makers in their choices. The report concludes with an overall framework for analysis in terms of Turkey as a regional security actor.

Introduction

This report analyzes Turkey’s role as a regional security actor in the Black Sea, the Mediterranean and the Levant regions.

The research team’s interdisciplinary background has guided the research, allowing a comprehensive assessment from a wide range of perspectives, as no single theoretical framework could holistically explain Turkey as a security actor. The overall framework used in this project mainly grounded in the neo/realist tradition of International Relations, but it also heavily benefits from various foreign policy analysis methodologies and a political psychology approach.

The original data used in this report was collected through closed online seminars with international and Turkish experts on different aspects of the project, online in-depth semi-structured interviews with experts and political elites from various political backgrounds, online free-flowed conversations with academics, experts, officials and advisors in Turkey and internationally. A comprehensive analysis of statements made by key political figures between January 1, 2015 and September 15, 2020 was also conducted.

During the project period, from July to December 2020, we have witnessed increased tensions in Syria, Libya, and the Eastern Mediterranean, and the resumption of war between Armenia and Azerbaijan over Nagorno-Karabakh. The pace of unfolding security-threatening developments in Turkey’s neighborhood is by no means extraordinary and indicates the complexity and the gravity of the issues the Turkish decision-makers have to deal with regularly in their near abroad.

Through this research, the team have identified key factors that guide the Turkish leadership in their strategic thinking concerning general foreign policy making and regional security issues. The research also reveals some of the long-term relational patterns between Turkey and its Western partners, and more recently with Russia. The report will reveal how Turkey is balancing its relations and policies between regions, between outside and inside actors, as well as between different actors to a varying impact in diverse theaters of operation.

In evaluating/mapping Turkey’s national capacity to cope with all the issues arising in its neighborhood, the research has identified a set of key variables affecting country’s defense/military capacity. As such, it has enabled us to sketch out a framework to understand the contours of Turkey’s role conception as a regional security actor.

The report is structured in three parts. The first part addresses Turkey’s historical and current strategic thinking and looks at the country’s foreign and security policies from a conceptual perspective. The second part looks at Turkey’s balancing acts between east and west, between Russia and its long-time allies, and among its regions. The third section assesses the balance between Turkey’s capacity vs. ambition in projecting influence beyond its borders. The concluding section sketches out an overall framework for analysis in terms of Turkey as a regional security actor.

Section I: Understanding Turkey’s Strategic Thinking

Whether consciously admitted or not, all countries follow long-term strategies, which are similar to highways, connecting one point in the past to a point in future passing through the present. As such, they politically and psychologically connect to an overall appreciation of a country including its history, cultural and ideological underpinnings, geographic realities, economic capabilities, future expectations, and understanding of its national interests as defined and constantly revived by its elites. These strategies provide a general framework and direction to the policy makers in their deliberations and daily actions.

It is common to come across public sentiments expressed in popular media and by political figures that “Turkey lacks a strategy” in its foreign policy. In recent years, this has been coupled with statements emphasizing that Turkey’s foreign policy decision-making has become increasingly centralized, idiocentric and aligned with the whims of its decision makers. Similarly, at the international level, there is no clear agreement on whether or not Turkey has a coherent general strategy through which its leadership formulates various governmental policies and allocates the country’s resources.

This lack of clarity about Turkey’s strategy is partly because Turkey does not have a tradition of publishing an official strategy or doctrine for its foreign and security policies, although various versions of the unpublished National Security Policy Document contain indications of an overall understanding of a strategy. Similarly, the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Ministry of National Defense do not usually share their policy directions and overall policy frameworks. Nevertheless, when looking through several decades of policy behaviour, one can identify several patterns of conduct that are consistent over the years and have survived governmental changes. Codified as patterns of Turkey’s grand strategy, these “structural determinants” of Turkish foreign policy could guide us in our long-term search for a general framework explaining Turkey’s foreign and security behaviour in its neighborhood.

Some of these patterns are also observable behind the policy lines of the current Turkish leadership, although they are not often mentioned in public and some of the implementation practices have substantially differed from the pre-AKP era governments. It could be argued that the current government is not willing to admit that publicly because they have been forced to follow similar strategic policies to its predecessors through the pressure of structural determinants (i.e., Turkey’s geography, history, socio-cultural characteristics, and the impact of international system). The long-term patterns of Turkish foreign and security policies, which could be classified as linchpins of Turkish strategic thinking, are briefly explained below.

Key Determining Factors

Strategic Geographical Position

Although Turkey has undergone profound changes since the 1920s, the value of its geographical position has not significantly altered – even if its relative importance to other states has varied over time. Turkey’s multidimensional geography has been used for political and economic benefit, but also represents a source of weakness when taking into account the number and combination of its neighbors. Some of the challenges resulting from Turkey’s historical existence in this geography include: civil wars in Iraq and Syria, a divided Cyprus, dissonance with Armenians, and an inability to reconcile with the Kurds. The importance and value of the location is further highlighted by recent increased international attention towards several regional conflicts in Turkey’s vicinity in recent decades. While the dramatic changes in the international system following the end of the Cold War and the contours of a changing world order had earlier challenged Turkey’s traditional policy of isolating itself from regional politics, it also forced Turkey to add regional components to its foreign policy, necessitating a renewed emphasis on its multidimensional setting and its role in bridging different cultures and geographies. With this understanding of Turkey as a European, Eurasian, and Middle Eastern country, Turkey’s political elites embraced its new positioning with multiple identities and historical assets. The reimagining of Turkey’s geography and role should be one of the key elements in understanding its contemporary regional policies.

Impact of International System

Turkey is a country that is closely attuned to the changes in international system. While it was able to attain certain level of internal and external autonomy after its independence, the post-1945 bipolar international system forced Turkey to choose a side as “a policy of neutrality was not very realistic or possible for a country like Turkey, a middle-range power situated in such a geopolitically important area”. The Cold War, while encouraging Turkey’s dependency on the West, also sustained unquestioning Western military, political, and economic support. As long as Turkey was threatened by the Soviet Union and the US was committed to assisting Turkey’s economic development and defense, there was no reason to question Turkey’s dependency on the West. However, the collapse of the USSR and the changing context from the 1990s has resulted in a reorientation of Turkish policy. In the 1990s, Turkey became a more assertive regional power, especially in Central Asia and the Caucasus. While during the Cold War, Turkey remained firmly within the Western bloc, since the end of the Cold War, its foreign relations have been dominated by a search for alternative connections.

Ten years after the end of the Cold War, the 9/11 attacks on the US and the Arab uprisings from 2011 onwards dramatically affected Turkish foreign policy. While Turkey benefitted from closer relations with the US in the immediate post-Cold War era, the US insistence to play a direct ordering role in Turkey’s neighborhood in the post 9/11 era – in the Caucasus, the Black Sea, and especially the Levant – has led to diverging interests and security perceptions. This divergence further accentuated after the Arab uprisings.

Furthermore, the primacy of Western actors in international politics has come into question because of the global financial crisis of 2008 and the China’s impressive economic growth. Other drivers challenging Western dominance include the rise of national populism, failure of Western migration policies, and Russia’s resurgence. Turkey has adapted to changing circumstances in the international fora and has increasingly focused on its neighborhoods –the Balkans and the Black Sea in the 2000s, and the Middle East since early 2010s. While there were both security/strategic reasons and ideological/political choices for this change, the underlying change in the international system has also played an important determining role.

More recently, Turkey has had a window of opportunity to assert itself as a regional power due to these systemic changes, coupled with the partial withdrawal of the US from its international engagements around Turkey, Europe’s struggle with resurgent Russia, and mixed outcomes of the Arab uprisings for regional geopolitics.

Ideational Inclinations of the Ruling Elite

In establishing the Turkish republic, the ruling elite carried out radical reforms to transform the country into a secular state and provided the basis of Western orientation, which became a key part of Turkish foreign policy during the 20th century. The Turkish elite’s focus on the West was accentuated in the 1990s and 2000s with a full membership bid to the EU and the subsequent negotiations which helped Turkey’s democratic transition and accelerated its international standing. The common understanding among Turkish elite at this time was that without its European connection, Turkey would be just another country in the Middle East. This belief paved the way for closer cooperation. However, the shared vision for Turkey’s future among its political, economic, and bureaucratic elite soon withered away and Turkey began to move away from the EU and started looking for alternatives in its neighborhood. While Turkey’s EU negotiations stalled as a result of a complex interaction of various political, cultural and economic developments both in the EU and in Turkey, Turkey’s Western vocation was increasingly questioned from cultural, national and security perspectives.

The rise of new political elite with the Justice and Development Party’s (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi – AKP) and the consolidation of its power in Turkish politics has also affected this change. Although exclusively pro-Western in its first term, a short review of the literature since 2007 when AKP started its second term in office, reveals that the new elite had solidified its approach to foreign policy with what was conventionally labeled as “the Turkish Model.” The Turkish model referred to the uniqueness of Turkey as a regional power and underlined its ideational role in Turkey’s neighboring regions – especially in the Middle East. The Turkish model was supported by the country’s proactive foreign policy and its use of “soft power” tools. In the words of the then-Chief Foreign Policy Adviser to the Prime Minister, Ahmet Davutoğlu, Turkey’s new proactive foreign policy redefined it as a “provider of security and stability” in its neighborhood. While the transformation of Turkish foreign policy away from its traditional model focusing on its Western connection towards a country with a role as regional security actor had started before AKP came to power, from 2007 the AKP-related elite tilted the balance of Turkey’s attention to its regions to the detriment of its internationally balanced position. Furthermore, the threats posed by the rising global security issues over the last couple of decades while Turkey’s economic capabilities were concomitantly improving, enabled Turkey to position itself as a regional security actor. The policy proved to be successful and further intensified the willingness of Turkey’s new elite to pursue even more assertive policy in its neighborhoods – especially in the Middle East.

Goals Hierarchy and Policy Drivers

Any country’s foreign policy goals are usually derived from the country’s overarching national interests and general strategy. In the Turkish case, many analysts have attempted to identify and explain the rationale behind Turkey’s recent foreign policy activism, often by relying on some specific variable such as Islamist ideology, the electoral alliance between the AKP and the ultranationalist Nationalist Action Party (Milliyetçi Hareket Partisi – MHP) or past injustices as perceived by the current leadership.

Through our research and interviews and conversations with political elite and experts close to the foreign policy decision-making units, we have pursued a bottom-up approach to identify these goals, coming up with an aggregate goals hierarchy pursued by the Turkish leaders in foreign policy arena. They are:

- Attaining strategic autonomy with a capability to maintain the country’s survival on its own, which involves having a flexible orientation in foreign policy, not compromising on perceived national interests and the essential issues for Turkey’s survival, security, and strategy, while at the same time not alienating possible or potential allies, as well as ensuring the continuation of foreign investments.

- Forging new partnerships while maintaining traditional alliances, together with a policy of strategic balancing to reduce Turkey’s over-dependence on its allies and to avoid direct confrontation with Russia.

- Becoming an exceptional country in its region to achieve material and political regional supremacy and respect, which would necessitate strengthening the military, expanding its footprint abroad with cross-border operations and/or military bases, and increasing its independence through development of domestic military industry and acquisition of much-needed weapons systems (such as S-400s) to defend itself alone.

Through this analysis of these prioritized goals, we can see that attaining strategic autonomy for the country in its foreign and domestic politics, often linked to Turkey’s survival in rhetoric, ranks at the top. Although the pursuit of autonomy in foreign policy began after the end of the Cold War and was further developed during the Davutoğlu era, it was significantly reinforced by the approach taken by the US and Europe in the aftermath of the attempted coup in 2016. The other goals, although are important in their own right, are seen as sub-goals that enable Turkey to achieve this strategic autonomy. The concept of autonomy here should be read being independent of foreign pressures in its policy making. It also includes the wish of Turkey’s political elites to have further flexibility in policy making regarding its commitments to the Western institutions. In other words, regardless of its membership to the Western institutions, Turkey’s political elites want to act in line with the West when it suits its interests and act with non-Western partners or independently, whichever best suits its national interests, without feeling undue constraints from formal alliances and partnerships.

Our project also addressed the main drivers behind the above-mentioned foreign policy goals of contemporary Turkish leaders, as a full understanding of any country’s foreign policy can only come when the motivation behind goals and policy lines is understood. The drivers here are understood as the activating issues, situations and perceptions that motivate the Turkish leadership to act towards fulfilling their chosen goals and national role conceptions. The following sections; Siege Mentality and the General Feeling of Insecurity, Domestic Power Consolidation, and Maintaining/Increasing Capabilities through Development, though not an exhaustive list, summarizes the most commonly considered drivers for Turkey’s recent activism in its foreign policy.

Siege Mentality and the General Feeling of Insecurity

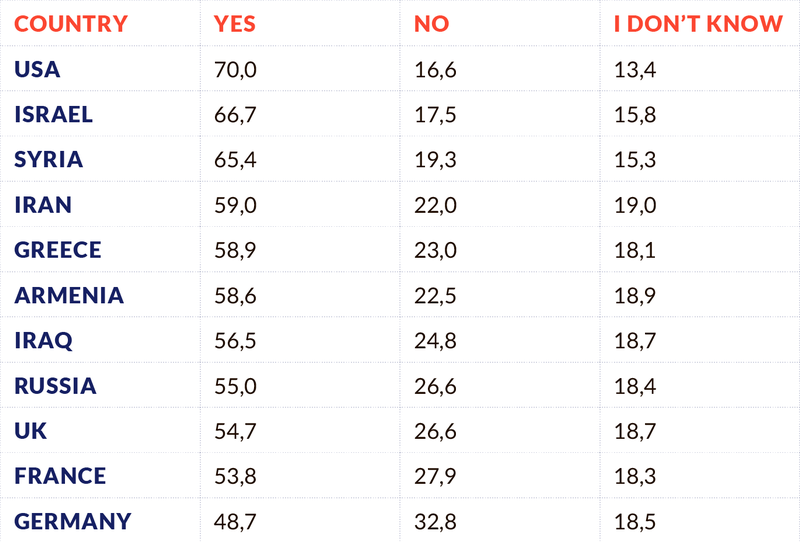

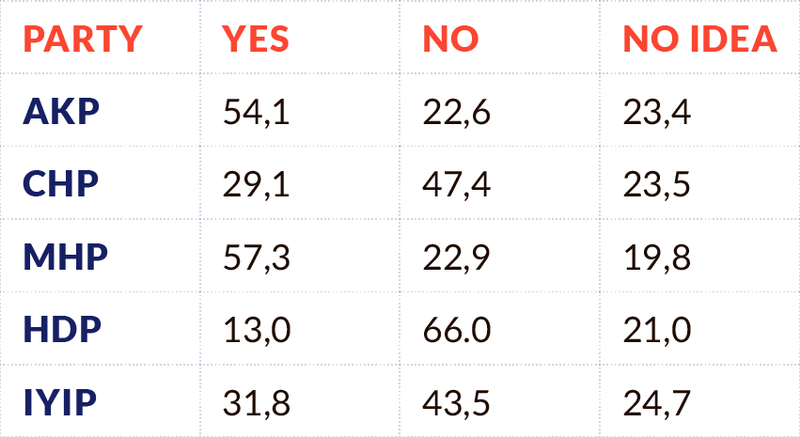

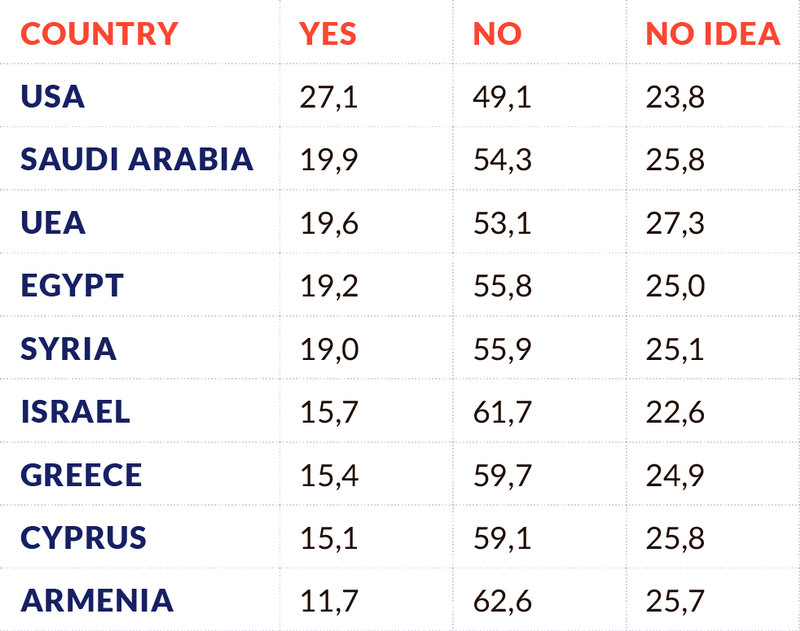

Turkey has been a security-minded state since its inception with international security concerns at the top of the agenda. This securitized tradition emphasizes the protection of territorial integrity, political independence and non-intervention in regional conflicts. Although the principle of non-intervention in regional conflicts has been eschewed since the end of the Cold War, the “security first” principle –which is closely tied to sovereignty– continues to shape Turkish strategic thinking. While the Turkish approach to security has traditionally been nationalist and NATO-centric, in recent years, it has shifted to highlight its autonomy in its neighborhood and defend its national interests more closely. This prioritization of security is not only seen in the decision-makers level, but is also reflected in public opinion (see Figure 1), which continually highlights the widespread threats it perceives from all quarters.

Figure 1: Do you think following countries threaten Turkey?

It is frequently argued that Turkey still suffers from a “Sèvres syndrome” – fear of dismemberment through foreign intrigues and interventions. This fear for country’s survival has been exacerbated in recent years with the internationalization of the Kurdish issue, especially in connection with its borders with Syria and Iraq where international terror groups can move across mountainous areas. As such, Turkey’s recent military operations in Syria, while countering the threat perceived from these regions beyond the Turkish border, also allows Turkey to maintain and control a security or a buffer zone to prevent border crossings.

Another aspect of the “siege mentality” and the “general feeling of insecurity” is the perception of loneliness, augmented by a reality that Turkey has few allies in a very complex and conflict-ridden neighborhood. This feeling is enhanced by a belief that its allies, such as European countries and the US, “are not always acting in tandem with Turkey on economic, political, or security issues”. The feeling of betrayal by the allies (re)surfaced due to the US’s close cooperation with the Democratic Union Party of Syria (PYD) and its military wing – the People’s Protection Unit (YPG), which are affiliated with the PKK. However, this dissonance between the threat perceptions of Turkey and its allies is not only due to the actions taken (or to be specific “not taken”) by its Western allies in Syria, Libya, and the Eastern Mediterranean, but also exacerbated by the Western (in)action in the aftermath of the coup d’état attempt in July 2016.

The Kurdish issue has been a driving force for Turkish politics on multiple levels: in defining the nature of the domestic political alliances, reconfiguring Turkey’s regional aspirations, defining its approach to other regional countries, and limiting relations with its international partners. Indeed, the Kurdish issue has frequently been described as one of the “major determinants of domestic political consolidation” among the military, the bureaucracy, and the political establishment.

Recent external threat perceptions also include developments from 2019 in the Eastern Mediterranean, where, feeling encircled by several countries, Turkey hastily designed a combination of diplomatic and military responses which drew the country into the Libyan Civil War and resulted in a clash with Greece in the Mediterranean and Aegean.

Internal threat perceptions have been successfully externalized with continuing internal and cross border operations against the PKK and the Fethullah Gülen affiliated persons and groups. In fact, after the failed coup attempt in 2016, large parts of Turkey’s foreign and security policies have been geared towards dealing with domestic and external factions of what is now called Fethullah Gülen Terror Organization (FETÖ) and the growing autonomy of the Kurdish groups in Northeastern Syria that is supported and protected by the US. At the same time, the government’s attempts to build civilian oversight and monitoring mechanisms over the military from early 2000s onwards was first aided by the EU integration processes, which the government frequently used as justification for its reforms and crack downs on Ankara’s bureaucratic tutelage regime. Later on, the process intensified with the implementation of the Presidential system and an even tighter grip of the political (civil) control over the military with the cooption of former Chief of General Staff, General Hulisi Akar, as the new all-powerful Minister of Defence.

The fear of dismemberment and loss of territory continues to hound Turkish national security thinking. As President Erdoğan declared in his Victory Day speech on August 29, 2019, “Turkey pursues [the] same determination to protect its national survival as it did 97 years ago”. Hence, the shadow of the Sèvres Syndrome continues to impact both Turkish public opinion and the political elite. The primary concern of Turkish political elites and the top decision-makers seem to be keeping the state as a “stable territory surrounded by a volatile milieu”. To achieve this, Turkey has recently moved from a defensive position to a more offensive one. As such, recent changes in positioning in Iraq, Syria, and the Eastern Mediterranean have forced Turkey to re-think its national security architecture and foreign policy and security strategies. In response to recent regional geopolitical changes, President Erdoğan stated in January 2020 that “Turkey will continue to vigorously defend its rights and interests abroad. The country’s future and security begin far beyond its borders”. Similarly, the decision to send troops to Libya was presented in Turkey as a “rejection of claims against Turkey’s interests” and attempts to force Turkey to submit international forces that conspire against Turkish interests. This is in contrast to how it was framed from abroad as Turkey “flexing its muscles” and attempting “to become a power broker in a volatile region”.

According to Erdoğan Turkey has risen under his administration to a position where its voice is heard on every regional and global issue. As a result, unnamed “international powers” are continuously presented to the public as trying to undermine Turkish power to prevent it from becoming an influential country “again” with power to shape the world. Thus, Turkey today wages “a struggle against those who seek to -yet again- condemn Turkey to modern-day capitulations.”

Domestic Power Consolidation

Another important driver behind Turkey’s foreign policy activism in recent years has been the electoral alliance created between the AKP and MHP, as well as nationalists and Eurasianist groups within the state apparatus in general. The alliance clearly drives current Turkish policies in Iraq and Syria, and is increasingly affecting various foreign policy issues, especially in relation to Turkey’s Western alliance and the Kurdish question. Turkey’s Syria policies have become increasingly tangled with domestic political developments and the AKP’s need for domestic support to stay in power.

Many surveys have already shown that in the long-term foreign policy actions do not garner more votes for the government. However, in the case of, for example, Turkey’s cross-border military operations, the stimulated issue-based support due to “rally around the flag” concept can be seen at two levels:

a) It works in reality as a short-term “rally around the leader” effect. Hence the expectation among the government circles that, should the public support for the leader increases in the short term, this could be translated into a long-term voting intention if sustained with similar policies down the line; and

b) In almost all cases in Turkey, the public exhibits increased support for the nation and troops while an operation is taking place, which creates a vicious circle of operations after operations in an attempt to keep the support up. Although this does not necessarily translate into a long-term voting behavior, it could be kept alive if the sentiments could be sustained through series of such interventions abroad. Hence, many analysts argue that the government continues to create foreign policy situations where military force or coercive means can be used repeatedly.

For example, several public polls conducted by the Metropoll Polling after the four operations in Syria showed that these cross-border operations garnered around 70% overall support. However, the same poll also showed that this support came as the second version of the “rally around the flag” concept, and the overall support did not transform into the “rally around the leader” model – and did not translate into votes.

In the structured webinars organized for this project, experts argued that the public support for the operations in Syria came from a clearer understanding of the threat. However, looking at the Eastern Mediterranean, different results appear – a September 2020 poll shows that only 23% of the population supported military solutions while 75% preferred non-military policy options. Thus, although the government’s rhetoric feeds the nationalistic sentiments of the population, without an accepted enemy image or a clear threat perception, the majority of the population is against military escalations.

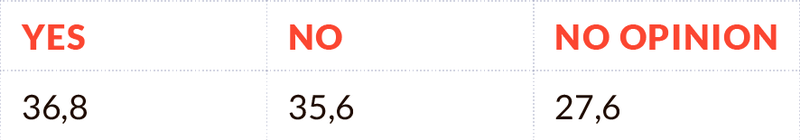

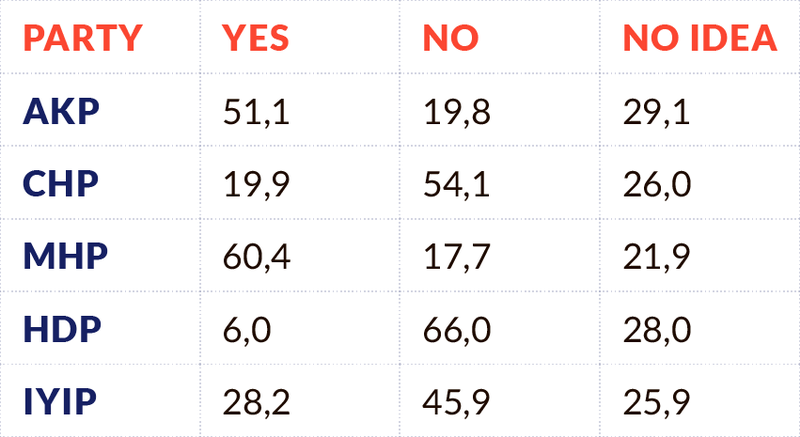

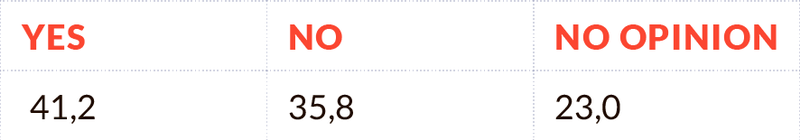

Figures 2-5 show that military presence abroad (bases, other installations and Turkey’s cross-border operations against terrorist groups) garner higher support among the voter base of the MHP – even more than AKP constituency. This extends the government’s activist – i.e. use of threats and force – foreign policy that we have seen in recent years.

Figure 2: Support for Military Presence Abroad

Figure 3: Support for Military Presence Abroad by Party Affiliation

Figure 4: Support for Cross Border Operations

In general, do you support Turkey’s cross-border operations?

Figure 5: Support for cross-border operations by party affiliation

Some of our interviewees argued that President Erdoğan pursues various foreign policy actions in order to increase his hold on power. Others argued that policy making is driven by “whatever works to raise the popularity of the government at home, regardless of the long-term consequences”. In the context of the poll results in figures 2–5, the popularity hike is pursued to a temporary effect and does not seem to translate into actual votes in the longer term. As such, foreign policy, seen to underpin President Erdoğan’s domestic political trajectories and his strategy to hold the current coalition together, reflects a highly nationalistic approach. On the other hand, some argue that Turkey’s geopolitical reach and wish to dominate its neighborhood has overcome the political divide, meaning that a change of government would only make a small difference in terms of Turkey’s challenges and its responses to them. However, we need to underline the fact that foreign policy plays a key role in holding together the domestic political coalition that AKP has established with the MHP.

Maintaining/Increasing Capabilities through Development

From the early days of the republic, increasing the nation’s wealth and industrial development has been seen as both a way to increase the welfare of its citizens and also to extend the country’s power base. It has also had an international component due to country’s chosen manner of development. Thus, by the end of the Second World War, Turkey favored closer relations with the West – both because of security concerns, and also though a realization that the country needed extensive economic support to stimulate the economy after years of austerity. In the post-war period, the US was the only country with the capacity to expand economic aid to Turkey, a fact that was clear through Turkey signing agreements with the US that, in terms of security, were based on the Truman Doctrine and economically on the Marshall Plan. It is important to note that Turkey joined the Organization for European Economic Cooperation (OECD’s predecessor) in 1948, four years before joining NATO. Since then, Turkey-US relations have always had the two pillars of economy and security, which were finally linked with the signing of Defense and Economic Cooperation Agreement (DECA) in March 1980. This agreement allowed US access to 26 military facilities in Turkey in return for an extensive military and economic aid package.

In the 1980s, as the demands from the growing Turkish population and dysfunctional Turkish economy forced Turkey to open up and integrate with the global economy, Turkey’s Western connection was again strengthened. It also led to the unprecedented move by the then President Özal to articulate his “Economy First” principle, putting it briefly ahead of security and foreign policies. Similarly, Turkey’s opening to its neighboring regions in the 1990s and 2000s related to the needs of a growing economy, demands of the middle classes, and aspirations of a young and increasingly educated population. These aspects of Turkey’s international connections do not simply derive from the preferences of the ruling classes or the wishes of a leader, but reflect a long-standing structural imperative that is not easily alleviated by choices or preferences of different governments or decision makers.

Thus, to achieve Turkey’s long-term domestic goal of a sustained economic growth becomes an important imperative behind pursuing a foreign policy that does not alienate potential investors and the country’s trade partners. More recently, Turkey’s attempts to diversify its external trade base by extending to the Middle East and Africa also clearly relates to this, and connects to Turkey’s earlier active involvement in solving regional problems in 2000s.

However, the more interventionist policy of 2010s has negatively affected this foreign policy-economic development connection. As such, much recent developments indicate that the government sometimes tries to resolve the downturn in foreign direct investments by promising reforms and indicating new foreign policy that align closer with Turkey’s Western partners. These same considerations could be motivating the recent promises of economic, political and judicial reforms and the human rights action plan. President Erdoğan’s statement, after years of dissonance with the EU, that “We see ourselves in Europe, not anywhere else. We look to build our future with Europe” also demonstrates this. This sudden turn can be read in light of Turkey’s increased economic problems following the two sharp contractions in two years and the dire need for foreign direct investment. According to Kouamé and Rab, Turkey needs to “refocus attention on structural reforms and build back a resilient economic system that propels it into the high-income group of nations”, which should be seen in connection with the national role conceptions of the current ruling elite that sees Turkey among the more influential global countries and also with the domestic power consolidation wishes of the government.

Finally, economic development links directly with the development of indigenous military industrial complex, which is seen absolutely necessary if Turkey is to achieve autonomy in its foreign and security policies. The development of a local defense industry is clearly linked to the improvement in military capacity which then motivates more adventurous foreign policy initiatives in challenging the status quo in Turkey’s neighborhood, such as in Syria, Libya, and the Caucasus.

Contemporary National Role Conceptions

Studies that examine the national role conceptions of Turkey detect several alternative roles for Turkey. Turkey’s previous national role conceptions include Turkey as a “bridge between continents”, “gateway of civilizations”, “model country” and “active independent country”. Further, there is a widely shared understanding of Turkey’s role that conceptualizes the country as a significant actor in all its regions – diplomatically, militarily, politically, and culturally. The current government has used this perception to steer Turkey towards activism in foreign policy in its neighborhood. Through our analysis, we found two current (additional) role conceptions: “Order Builder in the Neighborhood” and “Dynamic Regional Key Country.” Through our research and interviews we have identified some of the role-specific responsibilities/targets that the current Turkish leadership ascribe to:

- Countering Russia in the Black Sea, the Caucasus, and the Levant region

- Fighting radical extremist groups in the Middle East and North Africa

- Balancing Iran’s influence in Syria and Iraq

- Balancing US support for the PKK in the Middle East in general and in Northeast Syria in particular

- Balancing Russian and China’s influences in Central Asia, especially with regards to Turkic states

- Filling the gap created by the withdrawal of the US from, and the end of the attractiveness of the EU, in Turkey’s neighborhood

- Opposing other regional countries (such as the UAE, Iran, and Saudi Arabia) filling the above-mentioned space.

From the above list it can be established that: (1) both the practice of balancing and the role as a balancer is seen as important; (2) the Turkish leadership has an opportunistic outlook to increasing its regional influence that can be achieved through active engagement, and; (3) Turkey views itself as a responsible actor – THE actor –who, on behalf of the Western block, counters Russia and fights terrorism in its neighborhood, while at the same time countering “imperialist” tendencies of other states in Africa.

These role perceptions go hand in hand with specific action-prescriptions. One interviewee argued that Turkey cannot solely rely on diplomacy to execute these role-specific targets and thus needs a significant military presence in these areas. The policy-making elites also underline that Turkey needs to actively use its intelligence apparatus to support its engagements in these regions. Turkey would thus be the regional power asserting itself as one of the primary actors that defines the outcome of major regional crises. Some of our interviewees also argued that Turkey has already been an important player in the regions that it is actively engaged today, and this connection shapes the way it acts. Some argued that the “Western countries are imperialist, their presence is foreign and therefore unsuccessful”, while Turkey’s presence is “non-imperialist, local and more natural”. Further arguing that, because of its Ottoman Empire history, Turkey has more links to the peoples of these regions.

Others, however, argued that Turkey can still be seen as a foreign actor and an imperialist country, and that Turkey’s motivations are not much different than those of European countries. They recognize that, while the government might be motivated by justice and a need to help dispossessed peoples, Turkey’s leadership is also motivated by power, prestige, importance and a desire to rule over others – these motivations are not so different from other powers. We should note that these role perceptions are significantly shaped by the political polarization in Turkey. While the pro-government elites in Turkey see Turkey’s role as order-setting, the oppositional elites criticize this perception as being both imperialist and aggressive.

Regional Security Actor

There is a widespread perception amid the foreign policy community close to the government that “Turkey is an important regional security actor within its neighborhood”. This perception is somewhat based on a misleading understanding of the “regional security actor” concept. The pro-government pundits continuously use the concept to refer to Turkey having the power to decisively influence the security environment in its neighborhood. In theory, however, the concept is neutral and refers to any state whose actions and motivations in international security are heavily regional, as opposed to interregional or global security actors. In theory, all security concerns are primarily generated in the immediate neighborhood of any given security actor. Yet the influence and capacities of these actors significantly differ.

Turkey has always been an important actor in its neighborhood and Turkey’s influence and footprint within regional security is significant – whether positive or negative. However, some of our interviewees argue that Turkey has recently shifted from being a “security provider” to being a “security actor.” In their framework, this shift refers to the fact that Turkey now defines the security scene around itself and its ability to affect the regional power balances. For example, they argue, Turkey previously contributed to the security of the Black Sea region “through the OSCE in times when the region witnessed destabilization” because of terrorism and refugees. Likewise, Turkey provided security to Europe by “acting as a security-wall between unstable regions and Europe” and through its NATO membership, “stood against Russia in the Southern Flank”. However, others suggested that Turkey had not been an autonomous actor and its importance and role in the geopolitics of its neighborhood before the AKP was conditioned by its connections with its Western partners. With the AKP’s rise to power, according to this pro-government interviewees, Turkey has become a “regional security actor” with an increased strategic autonomy.

According to our pro-government interviewees, this security actor position emerged due to domestic political stability, a proactive foreign policy, and development of national defense industry. Turkey is now prioritizing its role as a regional security actor and is thus implicated in all the security challenges in its regions: in the Black Sea, in Syria, in Iraq, and in the Eastern Mediterranean. Indeed, while there has been much talk about Turkey’s hard power leaning foreign policy, when you look at the geographical scope of this activism it is largely centred on the Turkish near abroad. Our interviewees agreed that Turkey will continue to be a “security actor” in its regions, regardless of which political party is in power. In other words, pro-government analysts almost unanimously felt the need to mention that although Turkey’s regional role has continuity from earlier periods, the way it manifests itself today has changed significantly.

This increasing emphasis on (re)framing the Turkish foreign policy as a regional power also corresponds to the claims that Turkey is not only a regional power, but also a “central power” that has to trust only itself to secure its interests. This role conception has earlier versions throughout the republican era, though the pro-government pundits painstakingly refrain from mentioning them when analyzing current policies. According to our pro-government interviewees, Turkey as a central power believe in projecting power and assuring national security in military terms because they feel that they have exhausted all other options.

Our analysis demonstrates that Turkey has acquired a regional security actor role – both in academic terms and in the eyes of its decision-makers. Moreover, it is increasingly being seen in this role by outside powers – although not always with approval. However, this is not a new role for Turkey as it has always been an important regional actor, even when it did not pursue this position. Throughout the AKP period, however, there has been a conscious effort to re-focus Turkey’s attention on its neighborhood instead of the West, and to re-conceptualize Turkey as an autonomous foreign policy actor in line with the domestic discourse. The pro-government interviewees argued that Turkey uses military means because it has exhausted all its options – the country is isolated in a dangerous neighborhood without allies that share their national security concerns and interests, and it is not being accorded the status it deserves regionally or otherwise.

Strategic Patterns of Behavior

Within the above-mentioned constraints, drivers and role conceptions, several strategic patterns of behavior emerge, some of which correspond to Turkey’s earlier foreign policy lines, others stem from previous policies, and others are recent additions or expansions. “Balancing major powers in international relations” and “attaining regional supremacy” are two of the more prominent patterns to have emerged from previous policies and have shifted with the AKP coming to power. These two concepts are closely connected and have come to dominate Turkey’s recent activism in its foreign and security policies, both are discussed further below.

Balancing (and Countering) Major Powers in International Relations

During the latter part of the Ottoman Empire, the practice of balancing major powers was a strategy to preserve the status quo and slow down the loss of territory. It was further used as a tool during the Independence War (1919-1923), during the Second World War (1939-1945), during the detente period (from the late 1960s to mid 1970s), and from 2010 – as can be seen through Turkey’s balancing act between its Western allies and its regional partners, chiefly the Russian Federation. Russia’s countering effect against the US has become increasingly important in the post-Cold War era as Turkey has moved towards a more assertive foreign policy. The effects are especially important and pronounced in the Middle East and Black Sea contexts. As such, balancing major powers in international relations could be considered as one of the longest serving Turkish strategies in its foreign and security policies. This also clearly seems to be one of the aspects of the current government’s policy implementation today. As such, this aspect of current Turkish foreign policy deserves a further analysis which will be taken up in the next section.

On the other side of the coin, balancing major powers in its external relations, when combined with Turkey’s more activist and persistent policies in its neighborhood, have recently produced a somewhat unexpected aspect of the need to counter the impacts of major powers in different zones of influence which also at times necessitates confrontations with them. This stems from the fact that all the global powers, aside from China, are already diplomatically and militarily engaged near Turkish borders. Indeed, both the US and Russia have ground forces in Syria, in addition to their formidable political and diplomatic existence. The US also has forces stationed in almost all the Middle Eastern countries. Russia meanwhile has forces in Crimea (Ukraine), Moldova, Abkhazia and South Ossetia (Georgia), Armenia and Azerbaijan as peacekeepers. Similarly, various European countries have forces in Turkey’s vicinity, including the UK which have two sovereign bases in Cyprus, France which has an arrangement with Cyprus to allow French naval forces to use Cypriot ports, and a limited number of French and British special forces in Syria who are operating in connection with the US.

Recently, however, Turkey has demonstrated its abilities through its operations in Syria, Libya, Eastern Mediterranean, and its advisory position in Azerbaijan, when faced with geostrategic spheres of influence of global powers. Thus, as some pro-government analysts argue, Turkey’s proactive approach of dealing with troubles directly at their source brings Turkey into clashes with global powers. The clashes are a result of differing objectives in the region: Turkey aims to create room for its national interests and to garner more room for independent maneuver within disputed zones.

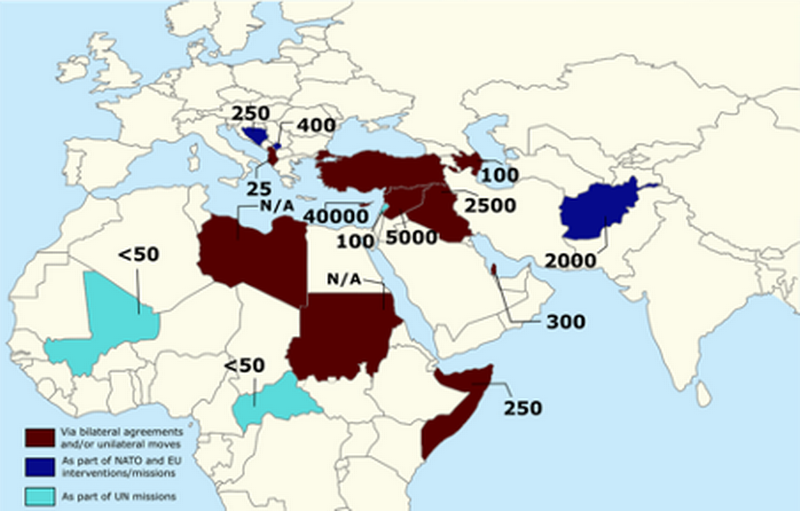

According to our analysis, the Turkish political leaders’ risk assessments for Turkish national security still include its historical adversaries and geopolitical competitors such as Russia, Iran, Greece, and Egypt. As a result, Turkey’s future security posture will still probably reflect its vital concerns of territorial integrity and political independence, whether in a transatlantic, European or unilateral context. As such, its ongoing operational involvements can be seen in a co-centric circle of interest with Turkish Armed Forces 1) deployments in cross-border operations in northern Iraq and northern Syria, 2) overseas military existence in Libya and the Caucasus, 3) overseas bases/installations in Somalia and Qatar, and 4) multinational military engagements in Kosovo and Afghanistan. While the first activities indicate the inner circle of Turkey’s engagements, the second and third constitute the outer limit of Turkey’s activities in recent years. These dimensions indicate not only Turkey’s ambitions in its foreign policy, but also the need to devise new foreign and security policies and strategies for Turkey. The limitations and constraints of Turkey’s increasing military engagements, which have recently extended to cover an area of roughly 55 million km2 from Libya in the West to Afghanistan in the east, and from Moldova in the north to Somalia in the south, will be taken up later in section 3.

Attaining Regional Supremacy through Power Projection in Near Abroad

Attaining some sort of primus role in its neighborhood has emerged as a widely shared goal in post-Cold War Turkey. At one time or another, almost all the parties across the political spectrum have supported an active position for Turkey in its region. This is evident through the policies followed by governments, with different political identities targeted at Turkey’s near abroad when facing crises or opportunities to expand, as well as frequent complaints from extra regional interference in regional affairs. It is clear from recent history that whenever Turkey has felt strong enough to play a regional role, and the focus of the global hegemon moved elsewhere, it has stirred to acquire a greater role in its neighborhood.

In the 2000s, Turkey used its growing economic power and political influence and focused on openings to new regions, especially in the wider Middle East. At this time, friendly relations with neighbors and playing facilitator role in regional problems were seen as essential for Turkey’s regional leadership, potentially leading to a global role. However, regional developments such as the Arab uprisings, the Syrian Civil War and the following “great power geopolitical rivalries” led Turkey moving away from its “zero-problem” principle in favor of “order builder” model – i.e., moving away from soft power to hard power instruments. With the rise of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIS), increased PKK militancy, sectarian rivalries, proxy warfare, and widespread refugee movements, Turkey moved to further interventionism in its neighborhood. The emphasis was then on a (forward) defensive posture rather than expansion of influence. These developments have affected both Turkey’s regional relations and its global standing.

As a result, Turkey has extended its power projection capabilities in its near abroad through its intervention in Syrian civil war, involvement in Libyan civil war where it sided with the Government of National Accord, its support to Azerbaijan in its attempt to regain control over its occupied Karabakh territory, and finally in the stand-off against the coalition of Greece, France, Egypt and Greek Cypriots in the Eastern Mediterranean. It has also established a military base at the Tariq bin Ziyad military base outside Doha, Qatar, in October 2015 and reinforced it with navy and air units in August 2019. Demonstrating an ability to extend its power projection beyond its immediate neighborhood, Turkey has also been part of twelve UN, NATO and EU led peace support operations abroad in Afghanistan, Kosovo, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Lebanon, Somalia, and Iraq (See Figure 6).

Turkey’s overt military and covert intelligence operations in Syria, Libya, and the Caucasus are also important from another perspective as it has managed to combine its national resources and forces to act in a designated overseas theater of operation with coordinated command configuration and without using NATO structures. For some of our interviewees, this clearly indicates that “Turkey is more than a regional power” but a central power with “enough capacity to reach beyond the Middle East”. While there is a common perception of Turkey in international literature that frames it as a “bridge” or “gate” between Asia, Europe and Africa, Turkey also clearly represents a dynamic center in its geography. The image of bridge/gate metaphor implying a somewhat static position, especially in the eyes of the political elite currently running the country, is no longer sufficient to represent Turkey’s reality as it has now achieved a “dynamic center” status that highlights its maneuverability in international arena in the eyes of its governing elites. Turkey’s recent activities in the wider geography indicates to this understanding.

Figure 6: Turkish Overseas Military Presence in Numbers as of January 2020.

Section II: Balancing Actions in Turkish Foreign Policy

As briefly explained above, “balancing major powers in international relations” has emerged as one of the consistently applied strategic behavior of Turkish foreign policy in recent years, although it has its roots in earlier republican and even the imperial experience. As such, both the practice of balancing and the national role perception of a balancer are seen as important components of the current leadership’s understanding of Turkey’s international positioning. As a result, to advance its interests, Turkey frequently uses balancing both as a diplomatic and military tactic. The following section takes a closer look at the strategy of balancing by analyzing some of the relational patterns between Turkey and some of its Western partners as well as between Turkey and Russia. It will then analyze how Turkey is trying to balance its relations and policies within and between regions.

Balancing Between Russia and the West

Turkey’s relations with the West have frequently been problematic, even in its golden days. Ankara’s desire to be accepted as an equal member of the Western world has always been accompanied with a profound anxiety about the Western-dictated international order. As discussed in the first section, the fear of the West infiltrating the nation to exploit internal divisions had its roots in the trauma of the collapse of the multi-national Ottoman Empire. Despite inclusion in the political (Council of Europe), economic (OECD and EBRD), security (NATO, OSCE, now defunct Western European Union), and cultural (Eurovision, European Cup etc.) institutions of the West, this deeply held fear and anxiety over the possible dismemberment of the Turkish state by a combination of internal treason and external betrayal have exerted a strong influence in Turkey’s security culture and mainstream foreign policy agenda.

Turkey’s relations with Russia, and its predecessors has been historically problematic and hostile. Turkey and Russia have a history of competition over a shared neighborhood in which hostility and tension has informed the relations. This history still affects current decision-makers, despite the more recent upsurge in cooperation. The relationship between Turkey and Russia is characterized as an elite-driven process, mainly shaped by the agencies of Erdoğan and Putin, meaning that it is not institutionalized and thus lacks institution-building mechanisms, even in the main areas of interaction (economy, security and defense). Turkey does not trust Russia’s commitment to their interests and a general skepticism that is rooted both in the historical memory and in recent/current experiences prevails.

As discussed previously in the report, the Turkish leadership desires Turkey to be a regional power in its own right. As such, it perceives the need to balance both US assertiveness and Russian resurgence in its near abroad. However, the positioning of Turkey might also turn into a dual dependency situation, characterized by a vulnerability to Russia, an increased need for assurances from the NATO against a resurgent Russia in the Black Sea and continuing volatility in Syria. In the following, we discuss this balancing act and focus on the relational aspect of these regularly conflicting partnerships.

Turkey and the West

Throughout the Cold War, Turkey turned to the West and depended on the US for its security, and the Turkish economy was gradually integrated into that of Europe. Turkey also displayed a growing willingness to pursue even more deepening ties with the West in the aftermath of the Cold War, applying for full EU membership and upgrading its relations with the US to a “strategic partnership” level.

Even before the initiation of the accession negotiations with the EU in 2005, Turkish relations with Europe began to sour due to the EU admission of the Greek-Cypriot controlled Republic of Cyprus before the solution of the issue between Greece and Turkey, and despite the rejection of the Annan Plan by the Greek Cypriots in 2004. The growing anti-establishment political parties in Europe with their anti-enlargement and xenophobic positions against Turkish membership made matters worse and caused mainstream European politicians to take a firmer stance against Turkey’s full membership during the EU constitution referenda in the Netherlands and France. The frustration of the Turkish political elite grew as the EU enlargement went forward in Central and Eastern Europe and the Western Balkans without Turkey. Many believed that the EU was employing double standards, and that “the EU would not accept Turkey whatever Turkey would do”.

As relations soured with the EU, Turkey went through a process of “de-Europeanisation” where the EU membership has lost both its normative/political context and its leverage over Turkey as a reference point in domestic settings and public debates. The weakening of the appeal and influence of European institutions, policies, norms and values then led to a growing skepticism within Turkish society towards the EU/Europe agenda, strategic orientation, and European values that the country. As a result, relations between Turkey and the EU have shifted to a transactional mode, favoring bilateral to multilateral relations, rejecting value-based policymaking and focusing on short-term gains.

The 2016 migration deal is one of the more recent examples of the transactional relationship between Turkey and the EU. In the deal, Turkey promised to accept the return of all irregular migrants crossing from Turkey to Greece and to take necessary measures to prevent new migrants crossing the EU border. In return, the EU pledged to allocate 6 billion Euros for the refugees in Turkey, to accelerate visa liberalization with Europe and to upgrade the Customs Union. The deal was highly criticized because it was a short-term transactional solution to a normative and humanitarian crisis. While both sides focused on their short-term interests rather than a long-term structural relationship, the deal did not even resolve the underlying tension regarding the refugee flow between Turkey and the EU. In March 2020, the Turkish government declared its Greek border open to millions of displaced people currently in the country in a bid to pressure the EU into supporting the Turkish position in Syria. The declaration was followed by movement of refugees towards the border area which created yet another humanitarian crisis.

Another example of this transactional mode is the discussion on the modernization of the 1995 Customs Union Agreement between Turkey and the EU. As of 2020, Turkey is the EU’s 5th largest trading partner, and the EU is by far Turkey’s number one import and export partner (42.4%), as well as a source of investment. After several years of rapid growth, the Commission proposed in December 2016 to modernize the Customs Union to further extend trade relations, but the Council has yet to adopt necessary mandate in an attempt to create a leverage point on Turkey. The transactional mode also resulted in diverging policies among the EU member states towards Turkey. While Germany, under Merkel, have continued to have a form of appeasement policy with Turkey, Macron’s France had hardening attitude specifically on Turkey’s role in the Mediterranean.

Similar transactionality can also be observed in Turkey’s relations with the US. The relations were already tense at the beginning of the US military intervention in Iraq as the Turkish Parliament voted not to allow the transit of US troops from Turkey to Iraq. This blow to the US plans was followed by a major public diplomacy crisis on July 4, 2003 when the headquarters of the Turkish military personnel in Sulaymaniyah, northern Iraq, were raided by US forces who arrested Turkish soldiers and put hoods on their heads. This incident affected Turkey’s political psyche significantly.

The Syrian civil war has significantly complicated the relationship between Turkey and the US. Although the two countries worked together at the beginning of the war, Turkey soon realized that the US was not willing to invest significant resources to the war effort and lacked a definitive strategy. With the rise and territorial gains of ISIL, the US opted to work with and support the YPG through political and military means. This cooperation was perceived as an existential security threat by Turkey and has since created serious repercussions for bilateral relations.

Further, Turkey’s relationship with Russia has been affected by the US support to the PKK affiliated YPG and the almost non-presence of the US in Syria. While Russia and Turkey are not completely on the same page regarding Syria or the Syrian Kurds, Turkish government officials feel that Russia will listen to their interests – in contrast to the US who do not show due concern towards Turkish regional security interests. In fact, Turkey was only able to intervene militarily in Syria through an agreement with Russia regarding the opening of Syrian airspace in Turkey. Furthermore, Ankara thinks that Washington’s plans about the PYD could extend to the post-war design and rebuilding efforts in Syria, which, coupled with the existence of de facto independent KRG in Iraq, heightens Turkey’s concerns with regard to wider US plans in the Middle East vis-à-vis Kurds and Turkey.

In general, Turkey’s relations with the West have suffered from lukewarm condemnations of the 2016 failed coup attempt and the lack of early response. Turkish political leaders have accused Western capitals of directly or indirectly supporting coup plotters, or at best not giving enough support to Turkey’s democratically elected leadership. Washington especially comes under suspicion because the supposed mastermind of the coup attempt, Fethullah Gülen, still resides in the US, despite pressure from Turkey to deport him or curtail his activities. Relations with European countries have also soured over the issue as the European capitals have distanced themselves from Turkey as a result of the declaration of the emergency rule following the coup attempt which suspended various democratic and legal rights, bringing Turkey closer to authoritarianism.

Ankara, however, complained that its Western partners were not sensitive to the existential security concerns that Turkey faced, specifically regarding the Kurdish problem and FETÖ. Moreover, according to several interviewees, Ankara also fails to find support from Western actors when it deals with Russia, economic troubles, energy dependency, or refugees. Thus, as one our interviewees argues, the government now asks itself; “what is the use of the West?” More significantly, government critics and wider segments of Turkish society are asking the same questions. There is a clear skepticism about the West among the general public, which is affecting Turkey’s foreign policy thinking.

It is now a widely held belief that the West intends to destabilize Turkey through supporting Kurds or coup attempts. The perception is that although Turkey contributes to European security by providing a buffer zone for refugees, the West does not contribute anything to Turkey, either politically or economically. When it comes to security, the perception is that Turkey’s security needs have widely diverged from the US in the Middle East and the EU has become captive to the whims of its smaller members, Greece and Cyprus. This perception has also become one of the drivers of Turkey’s balancing act between Russia and the West. As one interviewee put it, government officials acknowledge that they are meet with criticisms when they travel to Western capitals, while they are welcomed with open arms when visiting Moscow. Moreover, the feeling of being left out of Europe has created sort of a bond between Turkey and Russia which encourages a closer relationship with a very strong emotional dimension that has observed different shocks in the relations.

The purchase of S-400 missiles from Russia by Turkey has created one of the most significant crises, not only between the US and Turkey but also between NATO and Turkey. The US administration responded by excluding Turkey from the F-35 program and the US Congress mandated the President to apply sanctions in compliance with the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA). On December 14, 2020, the Trump Administration imposed sanctions on Turkey and put a ban on all US export licenses and authorizations to the Republic of Turkey’s Presidency of Defense Industries as well as an asset freeze and visa restrictions on the organization’s president and other top officers.

Regarding Turkey’s relations with NATO, there was previously a general understanding in Turkey about the value of NATO’s contribution to its security during the Cold War, especially its nuclear umbrella. However, as threat perceptions have shifted especially since the early 2000s, NATO’s value has been increasingly questioned in Turkey. Similarly, there was a general understanding among the NATO members regarding Turkey’s value to the security of transatlantic area despite several problematic issues over the years between Turkey and some of the NATO member countries. Most of these issues were the result of a spillover of bilateral conflictual issues between member states into the Alliance and were dealt with diplomatically within NATO. However, the voices within NATO arguing that Turkey has had diverged sufficiently to question its value to the Alliance have increased recently. This aligns with voices within Turkey that argue that Turkey’s security needs have diverged from NATO to the extent that they should seek alternative security partnerships.

Within Turkey the Eurasianist/nationalist coalition within the government and the military increasingly argue that NATO does not respond to Turkey’s overall security concerns and that Turkey should design its own security strategies relying solely on its own power. Outside Turkey, one hears questions about the future of Turkey inside NATO and also occasional calls from high level allied politicians calling an end to Turkey’s NATO membership, even though there is no stipulation in NATO Charter allowing such a development.

In any case, seen from a realist perspective, the likelihood that Turkey and NATO would part ways is very slim. Although we see Turkey today engaging with states like Russia through strategic partnerships within the security domain, these relations will most probably not be institutionalized, and the strategic culture of Turkey’s security institutions will continue to be deeply attached to NATO. Furthermore, despite occasional fiery rhetoric, NATO provides regional and global deterrence for Turkey, which would be irreplaceable. Turkey is only too aware that left alone against resurgent Russia in its neighborhood, it might soon face an impossible choice between Finlandization and trying to put up a resistance against Russian pressures similar to the end of the second World War. Furthermore, Turkey would not wish to be outside NATO while Greece is still a member and Cyprus would soon become one if there is no Turkey blockage, which would unmanageably tip the balances in the Aegean and the Eastern Mediterranean against Turkey. NATO also has value to Turkey’s defence industry, security culture, force-multiplication, and civilizational connections. For NATO, too, Turkey is an important partner not only because of the size of its armed forces - the second largest within the alliance- and the competence of its soldiers displayed in different theaters of operation, but also its irreplaceable geopolitical position. The negative potential of having Turkey as an adversary in the middle of these region is unconcealable. Moreover, beyond the military/security field, Turkey’s presence within the Western structures with is Muslim-majority population provides irreplaceable political and cultural legitimacy in its connections in the MENA region and wider world.

To conclude, our analysis indicates that the relationship between Turkey and the West is currently characterized largely by transactionality on both sides. This lessens the West’s leverage and soft power influence on Turkey in issues such as pushing for democratic reforms. Although the Biden presidency emphasizes the role of norms and values more in bilateral relations and underlined a return to multilateralism, as of now, the major approach of the US to Turkey has not been radically transformed.

Having said this, a forced non-transactional approach at this point in time, where Western countries condition their relations with Turkey on a value-based approach would most likely lead the Turkish leadership to turn elsewhere. Furthermore, it would not have a positive impact upon the majority of the Turkish public either, as such a policy would come across as being founded on Western double standards - i.e., “the Western partners only talks about values when it suits them”. Thus, there exists an inter-dependency relationship between Turkey and the West that feeds the continuation of the current transactional approach, even if it is not the most productive one.

Although there are some obvious problems in the relationship between the West and Turkey in general, our research does not indicate that the relations will break in the immediate future. The structural ties between the two as well as perceived benefits for both, act as drivers to stay connected and committed.

Relations with Russia

The American alliance with the PYD and the Western reaction to the 2016 coup attempt became important factors in increasing anti-Western sentiments and encouraging closer relations with Russia. Both President Erdoğan and President Putin share the view that the unilateral actions of the United States around the world, and specifically in areas where their respective states seek a role, is one of the most significant problems in current global politics. Both Russia and Turkey are motivated to balance the interests of the West and demonstrate a certain disdain on the motives of Western countries which plays an important role in their relationship.

However, it is also important to note that both countries have competing geopolitical interests in the Middle East, the Black Sea, and the Caucasus, where the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan could always be a potential destabilizer for the relationship. However, there seems to be a recently emerging pattern in Turkish-Russian relations: When the parties come across a particularly contentious issue with interests difficult to reconcile, they agree on an interim resolution and leave the final settlement to the future. For example, Turkey and Russia were moved to the brink of war in the beginning of 2020 over Syria, specifically the status of Idlib, possible autonomy for the Kurds, and the role of the Turkish-backed Sunni opposition in Syria’s future. However, in March 2020, Turkey and Russia reached a ceasefire deal over Idlib which legitimized (at least in bilateral terms) and solidified the Turkish military presence in Idlib and stopped the attacks on Turkish military personnel which were threatening to unravel Russian-Turkish relations. The deal thus froze the situation in the area without a clear solution to the mutually exclusive interests of both parties. More recently, in the geopolitical competition in Libya, where Turkey and Russia emerged as competitors, they managed to hang on to an interim agreement instead of finalizing a settlement, as a result both emerged as the most consequential players in the region. While both sides accused each other of using their Libyan partners for their national benefits and employing mercenaries to bolster their positions, they were nevertheless able to agree on imposing a ceasefire line between main opposing groups while keeping other actors at bay.

Furthermore, these geopolitical tensions have not overshadowed the economic cooperation between the two countries. In fact, increasing economic cooperation and foreign trade patterns are major factors that explain the dynamics of the bilateral relations. Studies show that states with high levels of trade and institutional mechanisms that sustain trade are less prone to disputes than other states. By 2015, Russia had become Turkey’s third largest trading partner in imports (the first two being China and Germany) and eleventh largest in exports (the first two being Germany and the UK). Russia is also a major investment site for Turkish construction companies that flourished during the successive AKP governments as the Turkish model of economic growth was increasingly based on the expansion of the construction sector.

The economic cooperation between the two countries, however, is taking place in the context of a huge trade imbalance in favor of Russia. According to the World Bank, for every dollar worth of Russian imports that Turkey purchased in 2018, it exported just 15 cents of its own goods to Russia. Further, it would be relatively easy for Russia to “exit” its economic relationship with Turkey as the existing deficit emerges from the nature of the bilateral trade relations, in which Turkey’s gas and oil imports constitute a major portion of the overall volume. In 2018, Russia was Turkey’s top supplier of natural gas and provided fully 47 percent of Turkish natural gas imports. Russia also provided 36 percent of Turkey’s coal imports during the same year. The over-reliance on a single country has long been regarded as both an important energy security issue, and an important matter for Turkey’s overall national security. AKP governments therefore proposed using nuclear energy to diversify Turkey’s energy resources. However, the contract for the Akkuyu nuclear power plant, the first in Turkey, was also given to a Russian company, Rosatom, which increased worries about granting Russia control over a significant part of electricity production and generation. On the other hand, Turkey was able to substantially decrease the percentage of Russian gas in its imports in the last two years as cheaper shell gas from the US as well as more Azerbaijani gas became available. As the long-term gas supply agreements with “buy or pay” stipulations between Turkey and Russia are ending, 2021 will see negotiations on the future of gas trade between the two countries.

The transportation of energy resources, especially natural gas, is another vital issue which, beyond its economics, significantly alters power projections and geopolitical interests. In October 2016, Turkey and Russia signed a deal on TurkStream, which became fully operational on 1 January 2020, and will make Turkey an important hub for European gas market. For Russia, the pipeline will substantially reduce its dependence on Ukraine and Eastern Europe, while helping to further seal its dominance over European gas markets. These kinds of deals clearly encourage both states to resolve their political differences, create more compatible regional policies, and prompt emergence of further economic networks.

We need to note here that the rapprochement between Turkey and Russia is not necessarily based on an attraction between authoritarian regimes. Rather, the resemblance that has facilitated cooperation between the two countries is the intense personalization of their decision-making processes. Unlike the Western countries – with a possible exemption of the Trump administration in the US – Russia has proven uniquely adept at courting other personalized regimes and displays a more flexible characteristic. However, while the highly personalized nature of Turkish and Russian decision-making procedures has strengthened bilateral ties, it has also fueled volatility in the relationship.

In fact, Turkey and Russia have been unable to develop their partnership of convenience into a more integrated comprehensive partnership. As a result, the relationship still remains transactional. This also indicates that the two countries do not share a mutually comprehensive security plan for the regions in which they are both active. Aside from their disdain of the West, the relationship mostly corresponds to short-term interests, lacks principles and norms, and moves forward with a highly personalized decision-making style of their leaders.

Nevertheless, despite this lack of a shared vision for the Middle East, the Black Sea, or the Caucuses, the striking feature of the bilateral relationship is its resilience in the face of repeated, and at times existential, crises. As one of our interviewees put it, Turkey has been able to display a very flexible foreign policy approach vis-a-vis Russia, while at the same time knowing that “Russia, as a very prominent actor in Turkey’s immediate neighborhoods, creates considerable constraints on Turkey’s foreign policy and strategy. Russia is basically blocking Turkey’s natural spheres of influences in the Caucasus, Northern Syria and Northern Iraq, and dominates the Black Sea. However, Turkey is limited in its confrontation with Russia because in certain aspects it is dependent on Russia –specifically in energy supply which it cannot easily diversify because of US sanctions on Iran.” Turkey overcomes this dilemma, according to one interviewee, by acting as a NATO member in certain issues and regions, specifically in the Black Sea, and sometimes acting as if it is an autonomous actor. This incoherence, according to interviewee, is a “balancing act”.

Another interviewee argued that Turkey is crucial in Western attempts to balance Russia. He argued that it is “hard to understand why the EU/Europe does not see the role of Turkey in all this. If one takes out Turkey from the equation, Europe will be much weaker; NATO will be much weaker. Why are European leaders so shortsighted on these issues? If Russia controls Libya, then Russia will comfortably threaten Europe’s security. Also, Russia will be an actor in Africa while Macron is dragging Europe into a big crisis with Turkey. The EU is overwhelmed with hatred towards Turkey, and this is why they do not see their strategic interest.”