Smallholders and food security in poor countries

3.1 Net sellers and indirect wage effects

3.2 Impacts of the Ukraine war

3.3 Adjustments to increasing local prices

4. Village-level poverty traps

6.2 Multiple constraints at the village level

6.3 Credit market imperfections

6.4 Micro-credit as a potential solution

6.6 Basic health and nutrition

6.7 Agriculture specific knowledge

6.7.1 Finding effective interventions

6.7.2 What type of learning works among smallholders?

How to cite this publication:

Magnus Hatlebakk (2025). Smallholders and food security in poor countries. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI Report R 2025:4)

The report discusses the role of smallholders in enhancing food security, recognizing that poverty is a main driver of food insecurity, with the majority of the poor being engaged in smallholder production. This implies that food producers are more likely to be malnourished than city dwellers. The report discusses the role of domestic and international food markets, and the gradual structural transformation that involves migration to urban areas. It is found that domestic food markets function well, bringing food to urban markets, while structural transformation is likely to take long, leaving the majority of the poor as smallholders in remote villages where production, and thus income, is constrained by a number of market failures. The report shows how poverty not only has a direct effect on food consumption due to lack of income, but also indirectly leads to a number of additional constraints, including at the village level. In contrast, large-scale farmers meet few constraints, leaving little room for policy interventions, although the report ends with a discussion of constraints, and thus interventions, that are common to small and large farmers. The main focus of the report is, however, on the constraints facing the poor, and the interventions that may counteract each of these constraints. It is found that a package of interventions is needed to counteract village levels poverty traps. The report also discusses in some detail the intrinsic problems related to learning and take-up of new techniques in smallholder agriculture, where the solution will vary with the local context and thus require very localized R&D, training and learning that is tailor made even to individual farmers.

Preface

Over the last few years, Norwegian development policy has had a focus on enhancing food security through support to smallholder agriculture. This report discusses whether it is a good idea to support smallholder agriculture rather than large scale agriculture, and which policy interventions are best suited for the purpose.

The report is an update of the CMI report Norwegian aid to food security, nutrition and agriculture (Hatlebakk, 2018). Compared to that report, the present one discusses more explicitly the choice between supporting small scale and large scale farming. It also offers a more detailed discussion of market failures that cause food insecurity, and policy interventions to address these failures. The discussion starts at the microlevel with smallholders who are constrained by incomes near subsistence level. This leads to constraints at the aggregate village level that may explain village-level poverty traps. Finally the report discusses constraints that all farmers face, not only those who live in poverty trapped villages.

The report is an output from the Development Learning Lab and is funded by the Research Council of Norway and Open Philanthropy.

Magnus Hatlebakk

August 2025

1. Introduction

The increase in world food prices following the covid pandemic and the war in Ukraine led to a renewed focus on food insecurity. At the same time there have been some, more or less tacit, voices in Norway in support of large-scale commercial farming in poor countries as an alternative to the present focus on smallholders. This report revisits these debates, based on a previous report by the same author (Hatlebakk, 2018). The report starts with a discussion of the role of smallholders, as compared to large commercial farms, when it comes to food security, and what role government interventions may play. We shall see that smallholders are harder hit by market failures that require interventions, while commercial farmers are likely to manage without government intervention. Then the report discusses to what extent the increase in world market prices affected this trade-off. We shall see that world market prices only to a limited extent pass over to domestic markets, which means that the increase had limited impacts on food security and the constraints farmers meet. The rest of the report first discusses these constraints, that is, the underlying market failures, and the importance of structural transformation. Based on the discussion of market failures the report goes on to discuss interventions that may help people better handle these. Since smallholders are harder hit, most of the report will focus on the constraints they meet.

While large-scale commercial farmers are primarily food producers, smallholders are either net-sellers or net-buyers of food, with higher prices benefitting sellers, while they hurt net-buyers. Furthermore, market failures imply that the two roles of food production and consumption cannot be separated. This contrasts with the theoretical model where markets are perfect and endowments of land, labor, capital and other inputs do not affect how much a farm produces: both smallholders and large farmers will rent in, or out, the inputs they need, and in theory operate at the same optimal scale. In reality we know this is not the case: most farmers operate a small piece of land that they either own, or have some other form of user right to, while a few farmers control large tracts of land and hire labor. In principle this may reflect constant returns to scale with all farm sizes being equally productive. But the most likely explanation for different scales of production is that underlying market failures imply that inputs that are under your own control are also the most effective. As a result, smallholders produce most efficiently at a small scale, while large landowners tend to hire labor so that they can utilize their own larger landholdings.

There is a large empirical literature discussing whether farm size matters for productivity, with no clear conclusion. The first contributions came in the early 1900s primarily in Russia. For a recent contribution, that also discusses the literature, see Ayaz and Mughal (2024). The core empirical problem is that it is hard to measure the quality of the main inputs, such as land, labor and capital, while at the same time the underlying de facto quality of each input will depend on the level of the other inputs. Any empirical relation between different combinations of inputs and combinations of agricultural outputs will thus reflect a wide variety in quality of inputs and production techniques.

As we shall see in the next section, some authors will argue that since economic growth requires a shift from smallholders to commercial farming, the latter must be the most effective. Assuming that markets are efficient, this is tautologically true: if commercial farms take over, they must be more efficient at the time of the transition. This should, however, only have implications for policy if there are market imperfections that hinder the transition. As we shall see, the market failures that do exist are more likely to hinder growth of smallholdings. Commercial farmers, in contrast, have access to capital and markets. They may be affected by some of the same market failures as smallholders, in particular poor infrastructure, but smallholders meet many additional constraints.

A core constraint is poverty itself. Poor people may not be able to raise the funds needed to repay loans, they may not be able to raise the collateral needed to get a loan in the first place, they may not be able to handle the risk of taking on new production techniques, they may not be able to make even small investments in assets such as livestock, and they may not afford to invest in human capital in terms of education, nutrition and health. Thus while commercial farmers have the resources to invest, their smallholder competitors do not. This hinders the gradual transition from traditional smallholder farming to potentially slightly more effective smallholder or medium sized farming.

To understand food insecurity better, we need to keep in mind that most poor people are in fact food producers. This implies that even food producers may lack food due to lack of income. The two roles as food producers and consumers may be interlinked due to market failures, as mentioned above. But even if the two roles are separate, meaning that smallholders run the farm as a business, and then use the surplus as any other income, we should be aware that food producers may be food insecure. Food security requires that food is available from the supply side, but also that consumers have the income necessary to buy food. Many smallholders have so little land that they are net-buyers of food, and even those who are net-sellers may need to restrict food consumption to be able to buy other necessities. As we discussed in Hatlebakk (2018) there is more than enough food in the world, so the main constraint on food security is lack of income. Lack of income is, in turn, explained by the fact that most poor smallholders live in remote villages characterized by multiple constraints that all have to be solved to get people out of poverty. We will below discuss multifaceted intervention packages that seem to help people out of poverty, also in the long run.

Another solution, at the individual level, is to leave smallholder agriculture and take up work in the modern sectors, including large-scale commercial farming. That is, we need to understand smallholders’ place in the structural transformation countries go through as they transition from an economy where most people are smallholders to an economy where most people are wage laborers. With economic growth people spend a smaller income share on food. As a result, farmers get a smaller share of total incomes. This means that either will the incomes of each farmer grow slower than the incomes of other people, or the number of farmers (or the time used on farming) will have to decline over time, which is an essential part of structural transformation. Some of this transformation will take place within agriculture as some smallholders leave their land and become agricultural workers.

Despite growth also in the non-farm rural sectors, the transition will normally involve extensive migration to urban areas, with, in the early phase of the transformation, many people settling in urban slums. As people move voluntarily, most of them will find a better life, although in equilibrium the last person who moves will tend to be only marginally better off. Since the most productive are likely to migrate first, we will observe that the average productivity in the city will be larger than in villages, while the marginal mover will have about the same productivity in both sectors. It will thus be a mistake to use the higher average productivity in the cities (or on large-scale commercial farms) as an argument for supporting the modern sector. The most productive are likely to be productive wherever they choose to live, while there may be more potential in supporting economic growth among the low productivity people who stay back in villages: that is, urban markets are likely to be more developed than rural markets, and people and capital thus more likely to end up where they can contribute the most to the national economy, independently of what the government does. In fact, government interventions are more likely to add distortions to the best functioning sectors of the economy. In the rural sector, on the other hand, where average productivity is low and markets tend to be distorted, there are strong arguments for government interventions. We will discuss these underlying market distortions and relevant government interventions in more detail throughout the report.

Some policy makers may still be concerned with the growing slums in urban areas, and thus argue that development policy should focus there. They forget that life in villages is also hard, which is why people leave for the urban slums. So policies to ease the lives of the poor should rather focus on where the majority of the poor live, so that they do not have to leave in the first place. Many of these policies will also ease the underlying market distortions in rural areas, as these to a large extent are both the cause and result of poverty. This vicious circle from poverty to market distortions back to poverty defines village-level poverty traps that demand a set of coordinated interventions that will be discussed below.

As mentioned, some of the distortions in village economies imply that we cannot separate smallholders’ role as producers from their role as consumers. While other people first get the best out of available livelihood options and then spend available incomes on goods and services, we know that many poor smallholders will consume large parts of their own production, with the consumption and production decisions being dependent on each other. This is, by now, the standard farm household model applied in empirical development economics, where household characteristics, such as number of people, age and gender composition may affect production, and productive assets, such as land and cattle, affect consumption decisions.

Even without any distortions, we know that a food price increase, such as the increase in world prices following the covid pandemic and the war in Ukraine, will affect smallholders differently depending on whether they are net buyers or net sellers of food. Note that landless people, including the urban poor, will be net buyers, and thus lose out when prices for food increase, unless the price increase leads to a sufficiently large increase in production of food and thus, for the rural landless, in agricultural wages due to an increase in the demand for labor.

The report starts with a general discussion of government support to smallholders versus large-scale commercial farms. The rest of the report goes in more detail on each element of this discussion, starting with food security. The first conclusion is that food is available from the production side, so that primarily lack of income limits the access to food, and this is the case even for (small-scale) food producers. This is followed by a discussion of international and domestic food markets where we find that international food prices do not matter much for local food markets, while the domestic markets normally function well, bringing food to urban areas. The discussion of food markets will include sub-sections on the possible indirect effect of food prices on agricultural wages, any impact of the war in Ukraine, and possible adjustments to higher prices among producers and consumers. Lack of income is in turn the result of market distortions and the following sections discuss distortions at the village level, followed by a discussion of structural transformation, where the village economy is integrated within the national economy. The report ends with a discussion of policy interventions, which will be based on insights from the preceding sections, starting with the subsistence farmer, via village-level poverty traps, ending with constraints that all farmers may face.

2. Small versus large scale

With economic growth countries will go through structural transformation, and thus urbanization, where labor shifts from agriculture to other employment and most investments take place outside agriculture. Some researchers, and to a larger extent private investors and policy makers, use these historical trends as an argument for government, or donor, intervention in support of the same transition. Among leading development economists we find arguments along these lines in Collier and Dercon (2014). They argue that the focus of agricultural policy should turn away from smallholders towards larger farms. A careful reading of the article indicates, however, that large is not necessarily very large. They agree with other economists that megafarms are not the future, and conclude: “While we have argued above that there is a good case for commercial agriculture, at a larger scale, this does not extend to megafarms”. They also say: “None of this will involve large state-led farms or geopolitically motivated megafarms, but it will require the creation of opportunities for serious, larger scale commercial investment in agriculture, and hybrid models in which smallholders interact with larger farmers and vertically integrated enterprises upward in the value chain”. They are not, however, clear on how this view should manifest itself in terms of interventions: “How to achieve it is less clear, and the evidence base for specific alternatives is lacking.” To the extent that Collier and Dercon discuss policy interventions we cannot see that they deviate much from the rest of the literature, which focuses on how interventions may help smallholders out of poverty traps, which in turn will allow them to invest and grow in line with larger farmers.

One may imagine that an underlying rationale for not supporting smallholders is that government support will lock them in poverty. But the reality seems to be the opposite: smallholders are in a poverty trap, where a one time support, if designed wisely, may lift them out of poverty and onto a track where they can themselves invest in the farm as well as in diversification into non-farm economic activities. We will discuss this literature throughout the report, including the broader discussion of structural transformation. For the latter, see a review by Barrett et al. (2017).

The alternative, of supporting large-scale farms, is more problematic: large-scale farmers are not in a poverty trap. There may still be some market failures that require government interventions, but these will be common for farmers of all scales. Typical examples are coordination on infrastructure and access to markets, thus for example roads, electricity, and storage facilities. We will discuss such general policies towards the end of the report.

The focus on smallholders follows from the fact that they constitute the majority of the poor and, as we shall see in the next section, are more at risk of malnutrition than urban dwellers, despite that they are food producers. And the focus on smallholder interventions follows from the insight that not only smallholder households, but even full villages in remote parts of Africa are in poverty traps where poverty in itself leads to market failures and market failures lead to poverty. Breaking this vicious circle is essential both to get people out of poverty, improve food security, and ensure a gradual economic growth in these villages.

We shall argue that food insecurity in most countries is the result of lack of income, rather than lack of food in the market. Domestic food markets work well in most countries, so that food easily flows from both smallholders (thus creating income for them) and larger farms to urban areas. This, in turn, is reflected in lower levels of malnutrition in urban areas, where incomes are higher. We also need to keep in mind that there is extensive non-food use (loss, animal feed) of what could otherwise be consumed by humans. Note that variation in prices, rather that quantity traded, is the best indicator of market integration. If production takes place close to where people live, then trade may be limited between geographical units, even if markets are fully integrated. Price differences are, however, not a perfect indicator of lack of integration, since transportation costs and lack of competition will contribute to price differences, even when active trade takes place. Taking these factors into account, the main conclusion is that domestic markets appear to be well integrated (see the introduction to section four below). Even seasonal prices do not vary much, Cedrez, Chamberlin and Hijmans (2020) find that: “Food prices in SSA were lowest three months after harvest (96% of the median annual price), and they were highest in the month before harvest (108% of the median annual price)”.

Large-scale commercial farms are in fact more similar to regular businesses than to small-scale agriculture. Commercial interests invest where they expect to get the most out of their funds, that is, they select a location, produce and scale they believe will maximize profit. Data on actual production on large commercial farms in poor countries is not easily available. The information we find suggests that large farmers produce some staple food for own consumption, while the rest of the land is used for cash crops. Similar to other industries, large commercial farms may contribute to poverty reduction through employment, but there is no rationale for interventions beyond general policies in support of economic development in rural areas. We will discuss these towards the end of the report. Smallholders, on the other hand, are important both as producers of staple food, and more importantly as consumers. The majority of the poor are smallholders, and as we shall see in the next section many are malnourished despite that they produce food.

3. Food security

Food security requires that food is available from the supply side and people have the income to access the food from the demand side. They must also be physically able to utilize the nutrients, which requires a healthy body. And these three factors should be available all the time, which is the fourth, stability, element of the standard definition of food security. If markets work well, then income will be the only factor that may limit people’s food security. In fact, one can argue that even income is unlikely to be a problem if the labor, land, capital, and insurance markets function well: labor and capital will move to where they are the most effective, and with the technology and capital available today this should give everyone incomes well above subsistence level.

Despite this, we observe widespread chronic malnutrition in many parts of the world, and more so in rural areas (Ameye and De Weerdt, 2020; Van de Poel, O’Donnell and Van Doorslaer, 2007), where the food is in fact grown. If we look at recent data, we find that out of 51 African countries, only one (Egypt in 2014) had a higher rate of stunting in urban than in rural areas in the latest available survey year. The mean, and median, level of rural stunting was 32% among the 51 countries, while the mean in urban areas was 22% (median 20%). The largest difference is found where you may expect to find it, in poor and/or undemocratic countries: Burundi (59% in rural and 28% in urban areas in 2016), DRC (50% in rural and 29% in urban areas in 2017), Nigeria (45% in rural and 27% in urban areas in 2018), Eritrea (58% in rural and 40% in urban areas in 2017), while the smallest differences are found in North-Africa, where rural malnutrition is relatively low (10% in Algerie and Tunisia).

The fact that the urban population has easy access to food indicates that food markets work well. We must thus find another explanation for high levels of rural malnutrition, with buying power, and thus poverty, being the obvious explanation. Despite that many of them are food producers, many of the poor cannot afford to buy, or keep, a sufficient variety and amount of food needed for a healthy diet. Later in this report we will discuss the underlying market distortions that may explain why people stay poor. The discussion will be based on recent research where large-scale randomized controlled trials (RCTs) support the conclusion that the rural poor meet a number of distortions, which means that it is not sufficient to solve one problem at a time. We shall argue that these poverty traps go beyond each individual, and are rather village-level poverty traps.

3.1 Net sellers and indirect wage effects

Before we go on to the village level, we note that it matters whether a food producer is a net seller or buyer of food. This is a major insight from farm-household models that have important policy implications even if there are no market distortions. A smallholder household that has so little land that they do not produce sufficient food for their own consumption will depend on other incomes to buy the rest of the food. They will thus be hit by food-price increases, similar to landless people in both rural and urban areas. There is, however, also a potential positive effect: some of the household members may be employed in agriculture, where they can indirectly benefit from higher food prices if this leads to larger production and thus demand for labor, which in turn may drive up agricultural wages. The latter will depend on the bargaining position of farm workers. With surplus labor we shall expect the wages to stay low. As the economy develops, and people to a larger extent get jobs outside the village, wages will go beyond subsistence level and tend to increase when there is a shift in the demand for labor.

Analysis of cross-country data indicates that this is the case most places, and that the wage effect even dominates the price effect, so that an increase in food prices in fact benefits the rural poor. This indicates that farm labor benefit as if they were net sellers of food, which in a sense they are as they contribute to the production. There may, however, still be areas with surplus labor, where wages will not increase sufficiently to dominate the negative effect of rising food prices.

To summarize this far, there is more poverty in rural areas, which in turn leads to inferior nutritional outcomes, despite that this is where the food is produced. An increase in food prices, however, will lead to higher incomes for food producers, including, in most places, also farm-workers. We will now discuss a potential main driver of local food prices.

3.2 Impacts of the Ukraine war

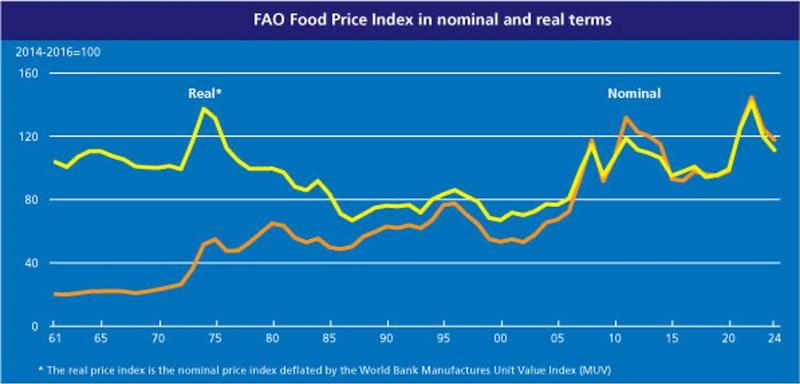

Note that it is local food prices that matters for poverty and food security. These are affected by international food prices, but maybe less than one may expect. The main recent drivers of international food prices have been covid and, in particular, the war in Ukraine. World food prices are now on the way down after the spike that followed the Ukraine war, as shown in Figure 1.

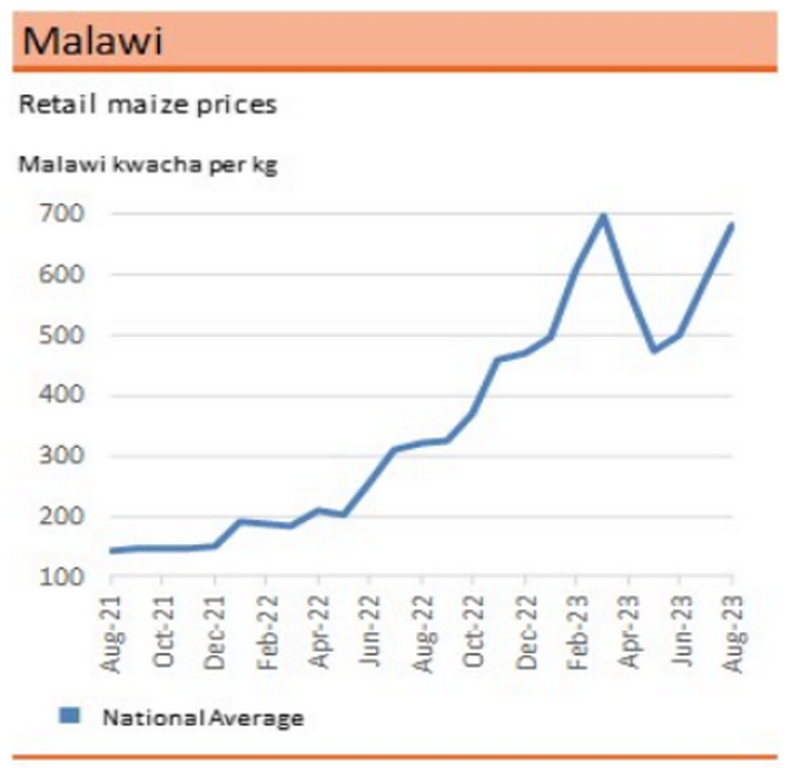

Despite well-functioning domestic food markets, world market prices do not necessarily affect domestic prices. Malawi is a case in point: maize is the main staple, with prices increasing from April 2022 till February 2023, followed by a decline and then again an increase until August 2023, as shown in Figure 2.

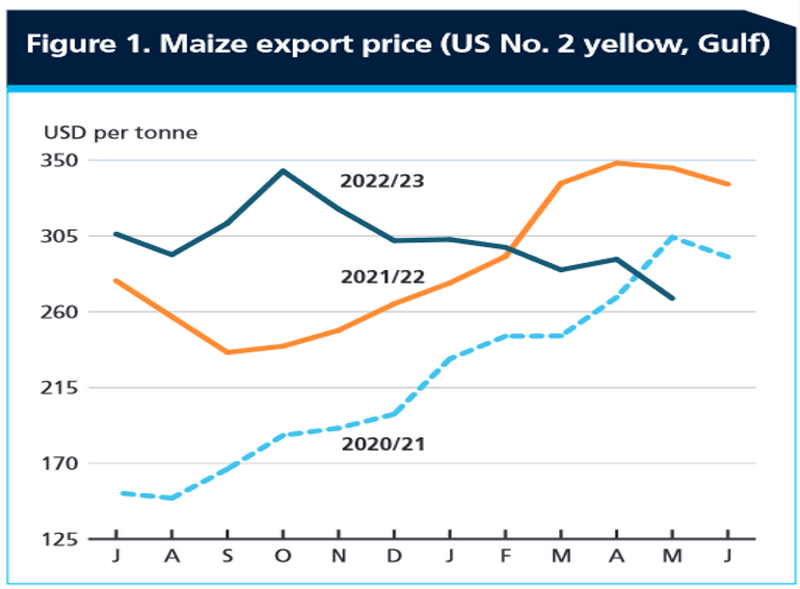

This contrasts with the international maize price that has declined since October 2022, as shown in Figure 3.

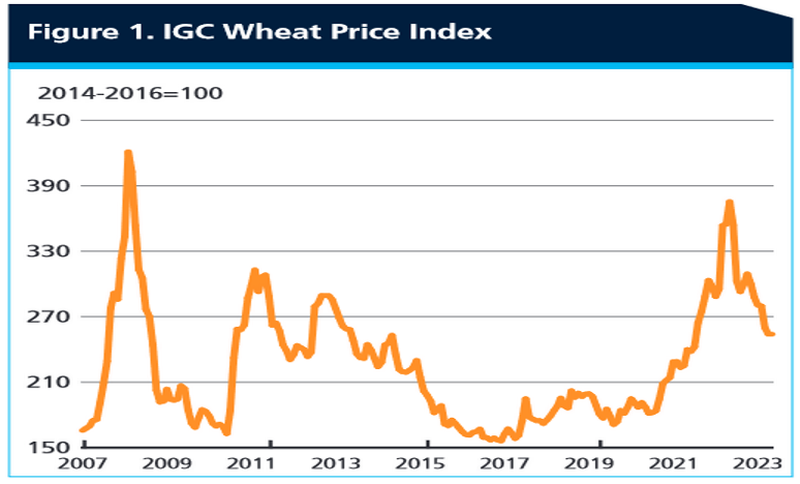

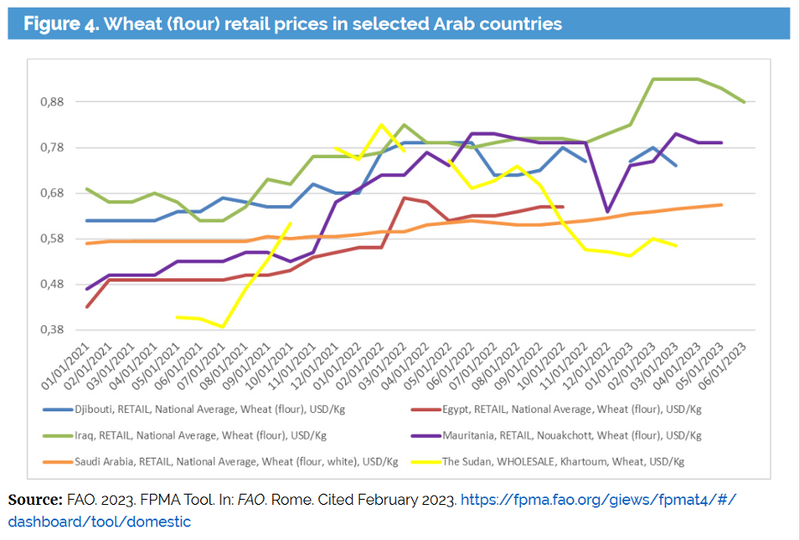

Similarly, the world wheat prices have declined after a peak in 2022, see Figure 4. This time, Malawi will not be a good comparison, while Egypt is, with its dependency on wheat import.

While the international wheat price declined, the retail price in Egypt, and comparable countries, has increased as shown in Figure 5.

We shall maybe not be surprised that even the largest importer of wheat, Egypt, which imports approximately half of their consumption, is not so dependent on what happens in Ukraine: despite being the largest wheat trading partner for Ukraine, still only 20% of Egypt’s import came from Ukraine during the years prior to the war (2014-2022). Going beyond Egypt and wheat, it is estimated that on average only 30% of changes in international food prices passes through to domestic markets.

3.3 Adjustments to increasing local prices

Since the price signals from the international market are not very useful in judging the risk of food insecurity, the focus should be on domestic markets. This also seems to be the strategy of the FAO, with their early warning system being a good tool for policy makers. Their focus is on negative shocks to production, which in turn may affect prices. A negative shock will not necessarily hit all local producers, and we shall expect a supply response as producers that are not directly hit by the shock may increase production as a result of better prices. Increasing prices will also normally lead to adjustments on the demand side, with for example less food being used as fodder. These adjustments to higher prices will reduce, but not cancel, the costs of the initial price increase.

Now, the demand for food will tend to be more sensitive to food price changes among the poor since real incomes will be more affected the larger is the share of income spent on food. That is, as food prices increase the poor will have less room to cut other expenses and will thus have to cut on food, in contrast to people with more money who can cut other expenses and maintain food consumption despite higher prices. The poor may, however, have room within the food budget to cut on high value products, such as meat, fish and even vegetables, before they cut on staples, such as rice, maize and wheat.

3.4 Food security summarized

Income is the main determinant of food security. People with sufficient income will pay what is needed to produce and transport food, and they will make sure to have safe drinking water, sanitation facilities and access to health services, so that the food is also efficiently utilized by the human body. As a result of purchasing power, food will be transported from food surplus regions to food deficit regions. In most countries we will observe that wealthy city dwellers will have sufficient access to food even during bad times. This indicates that markets work, and may explain why many economists tend to favor cash transfers in times of food crisis, assuming that this will help food markets to function also for the poor.

The majority of the poor live in villages, with many of them being food producers. Due to lower incomes than in urban areas we observe higher levels of malnutrition in the rural areas. The incomes vary over time, and those engaged in agriculture tend to benefit from increased food prices, while others, including the urban poor, are hit by higher prices. Since poverty is the main driver of malnutrition, and the majority of the poor live in villages, we need to understand the underlying causes of rural poverty, to which we now turn.

4. Village-level poverty traps

In a small remote village there will be few agents on the so-called short side of the market (employers, lenders, shop-keepers). High transportation costs, lack of information and potentially even threats, keep competitors away. The level of competition will thus vary empirically: it is found that domestic food markets seem to work relatively well, although the degree of competition in the value chain still depends on the type of transaction costs, and distance from producer to market.

Transportation costs matter more for local food prices than even international prices for the same product: Dillon and Barrett (2016) find that the change in local prices for maize (in East-Africa) due to oil prices is more rapid than the impact of international maize prices, and they find some evidence that in remote places the oil price has not only a more rapid impact, but also a larger effect than the international maize price. This indicates that domestic food markets are relatively independent of international markets, except for the role of fuel for domestic transportation.

While domestic food markets appear to work well, local strong-men seem to have more control in input markets (labor, credit, land). As a result of inferior contracts and few resources, poor people living in remote villages have limited purchasing power in addition to relatively high per-unit transportation costs as compared to urban markets, which in turn leads to food insecurity.

An underlying problem is asymmetric information, that is, workers, land-tenants and borrowers can to some extent hide their own labor efforts and risk-taking, and thus let employers, landowners and lenders take some of the costs of under-performance and risky decisions. These costs they may recover by offering take-it-or-leave-it contracts to the workers cum tenants cum borrowers. This insight has led to a large literature in development economics explaining the consequences for village economies, with the Nobel prize winner Joseph Stiglitz making some of the initial contributions (Stiglitz, 1974, 1985; Stiglitz and Weiss, 1981). Some of the main findings can explain why people, and even villages, are trapped in poverty:

As people are poor, they will need to borrow to be able to invest in new technology. But this introduces a classic problem: borrowers can hide from the lender both their true characteristics and the efforts they put into production and thus the ability to repay the loan. The lender may, in turn, end up lending to people who may potentially run away, spend the money unwisely, not being able to utilize the new investment, or just shirk in the efforts needed to use the technology. Adding to these problems, new technology may require skilled labor inputs, and by that workers may hide their potential lack of skills. The implication will be that farmers have to rely on simple, but inferior, technology and family labor that is more easily monitored.

In principle one can get around these problems by use of collateral, or self employment and self financing, but this will normally require some initial threshold of capital and skills within the village. Above the threshold there may in turn be higher demands for skills, and thus better incomes, and in turn more demand for local goods. The distribution of initial wealth and skills at the village level, and thus the share of households that meet these constraints, will determine what long-term outcome that will appear (multiple equilibria). Some villages will be in a poverty trap and others in a virtuous circle of economic development (Banerjee and Newman, 1993).

A big push may be needed for a village economy to transfer from a low-development trap with small-scale low-tech family farms to a path where households gradually diversify into non-farm occupations and investments in better paid businesses and occupations. Many of the market distortions described by Stiglitz and others exist also in more developed economies, but are less critical as people no longer live at subsistence levels, which in turn means that some of the constraints, such as lack of collateral or self-financing, no longer exist.

A big push can be facilitated by a combination of interventions: asset transfers or minimum incomes so that people are able to repay loans, credit programs so that they can get loans, skill training and basic education so that they can utilize any new investment, health coverage and agricultural insurance to avoid that they again fall below the poverty threshold. Such multifaceted, or graduation, programs have now been tested in many countries, and large-scale RCTs have shown that they have long-term impacts (Banerjee, Karlan, Osei, Trachtman and Udry, 2022; Balboni, Bandiera, Burgess, Ghatak and Heil, 2022). With the majority of the poor being smallholders, we will return to some of the components later in this report. But first we will discuss the links between village economies and the urban sector, as some may argue that instead of investing heavily in remote villages, one should rather focus on the fast-growing urban sector. This may include commercial agriculture, which can be considered as part of the modern economy.

5. Structural transformation

With economic growth there is transformation both on the consumer and producer side of the economy, with the two being closely linked as increased productivity gives higher incomes, normally for both labor and capital owners, which in turn leads to higher consumption. While consumption of necessary goods, like food, may also increase, they will, as we have discussed above, take up a smaller share of consumption, which in turn affects the production side since the producers of these goods will get a smaller share of total income. If labor and capital are allowed to move freely between sectors and locations, we will thus observe a transition from agriculture to other goods and services. With agriculture becoming relatively less important the structural transformation will involve migration to urban areas, unless there is a major increase in non-farm activities in rural areas. As there tend to be positive externalities between firms we shall, however, expect to see urban agglomeration, which in turn may lead to negative externalities for people in terms of congestion and environmental problems.

In both rural and urban areas the government should support activities that have positive externalities, such as R&D and provision of public goods, while at the same time attempt to regulate negative externalities. The sum of interventions will, in an ideal world, either support or slow down urbanization depending on the relative size of the negative versus positive externalities in both locations, with the need for a big push to get villages out of poverty traps being part of the equation. In the real world, we are concerned that policies will instead reflect political business cycles. For some time there has been a focus on the negative externalities of urbanization, with the hazardous level of air pollution in many mega-cities being at the fore-front, while there, at least in Norway, are signs of a turn towards a more positive view on urban growth, as illustrated by the above-mentioned media coverage, which tilts towards a campaign, by the Norwegian aid agency’s magazine Panorama.

As discussed above, at the micro level people and capital will move to get higher incomes. In equilibrium this means that the marginal mover will be paid about the same in all sectors and locations. There may be some difference, if some people prefer to live in their village, while others appreciate urban life, but in general the last person to move will tend to like both places about the same. There will however be some who benefit much more from moving, and others who benefit less and thus stay back in the village. On average we shall expect to see much higher productivity in the urban sector, but smaller differences in wellbeing among most people since they locate themselves in their favorite location. The higher average productivity in urban areas provides no information on the effectiveness of government policies, it may perfectly well be most effective to increase the productivity of the majority of the poor who live in rural areas. Individual success stories, which tend to be reported in the media, have little to tell us when it comes to economic policies and developmental interventions. Some of those who migrate will, just by coincidence, make it in the city, as will some of those who stay back in the village. Deeper analysis of policy interventions is needed.

6. Policy interventions

We know that with asymmetric information there will be room for welfare-improving policy interventions (Greenwald and Stiglitz, 1986). One may argue that in close-knit village economies there is not much asymmetry, as everyone knows everyone (in contrast to outside agents that may demand labor or provide credit). But this raises another issue as well-informed employers, landowners, traders and lenders, who may in fact be the same person, can utilize this information to design contracts that are efficient, in the sense that surplus is maximized, but in such a way that they themselves take the surplus. In the extreme, the local elite collude on extracting all surplus in the local economy. This will normally be driven by surplus labor and thus acceptance of subsistence level incomes, which in turn means that people are not able to raise collateral, repay loans, or self-finance investments. As a result they have to accept loans with high interest rates and labor and land contracts where they work long hours for minimal pay.

In these villages there is, as discussed, a need for a big push that can lift people above subsistence by way of income support or provision of assets, access to insurance, external markets, health services and basic education and training. With the majority of the poor being active in smallholder farming, this will include localized agricultural research stations and extension services (training in soil management, planting, etc.), agricultural insurance, direct support in terms of assets (livestock, machines), inputs (fertilizers, seeds) and access to markets (storage facilities, transportation, etc.). In more developed villages the subsistence constraint may no longer be relevant, but there will still be market distortions that need intervention. This includes under-provision of public goods, such as localized research and extension services, roads, electricity, schools and health facilities. And it may include help in developing markets, including insurance and credit institutions. Below we will start with the farmer and interventions related to subsistence constraints, then go on to the village level and big-push graduation programs, and end up with any additional interventions that are relevant for the rural economy at large. The discussion will, as mentioned, be an update on Hatlebakk (2018).

6.1 Subsistence constraints

In villages with excess supply of labor, poor people will tend to accept any wage that keep them going (the labor supply curve is flat). With such subsistence wages, they will have no surplus for investments. One may argue that the poor can finance investments by borrowing, but that will normally have to be repaid within a certain period, leading to instalments that will tend to be higher than the rental rate (Hatlebakk, 2015). Even if only slightly higher the subsistence constraint may bind, and the poor will not be able to take up loans. Thus even if purchase is profitable, they feel they cannot take up the loan needed.

Incomes will still fluctuate around subsistence level, primarily due to fluctuation in days of work rather than the wage rate, and even more importantly, they may meet extraordinary loss of income or expenses if they fall sick. In these cases they may accept loans with very high interest rates, even if they know that this will add to future burdens and hinder growth beyond subsistence level. The lenders, who may also be employers and landowners, know this and can (collude) on charging very high interest rates (Hatlebakk, 2009). As a result of incomes near subsistence level, and potential shocks that bring you back down if you are on the way out of poverty, many poor people will stay poor for a very long time, potentially all their life.

What will be the necessary policy interventions? Cash transfers will have to last long enough to finance repayments of loans, and will only work for households that do not meet negative shocks during the repayment period. It will also require that people are not tempted to spend the cash on consumption now that they can spend more than subsistence level.

A more direct intervention will be to provide the profitable asset in question rather than the incomes needed to repay a loan to buy assets. This will require that the government, or development agency, knows what will be a useful investment for the poor. This is far from straight forward, but should be easier when it comes to smallholder farming than for non-farm businesses where the possible investments are nearly endless. In smallholder farming a profitable investment at one farm is likely to be profitable also at the neighboring farm. This is, of course, far from a universal insight as natural conditions and human capital will vary, but still small farms in the same village will tend to be similar, and some learning between farms should be feasible. Allocation of assets may, however, need to be followed by training, or copying, of new techniques. And we know that it is far from certain that it will work. Since learning of new agricultural techniques is not unique to subsistence farmers, we will go in more detail on this later. Here we only note that asset transfers can be a useful alternative to cash transfers, and potentially more so for simple technologies that are likely to benefit most smallholders. Provision of livestock, which is a well known “technology” in most places, may be a good alternative, in particular if there is increasing local demand for milk and meat. Help in producing local vegetables and fruits may also be an alternative that utilizes slowly developing local markets, to the extent that these exist, which brings us to the next section.

6.2 Multiple constraints at the village level

Above we have described how poor people may stay poor for a very long time if they have incomes near subsistence level, simply because it will be too hard to save even small sums to repay a loan that may finance profitable ways out of poverty. An implication of this is that people with assets below a critical level will not accumulate more assets, a hypothesis with support in data from South-Asia (Balboni, Bandiera, Burgess, Ghatak and Heil, 2022). A further implication is that wealth distribution at the village level matters. For the same level of aggregate wealth, there will be more households below the threshold the more uneven is the wealth distribution. This is obviously true at any point in time. But since wealth above the critical threshold leads to investments and thus higher incomes and accumulation of wealth, the distribution at any point in time will also have consequences for the long-term development of the village economy. What is essential in these models is how credit, labor and entrepreneurship behave in the aggregate, and how the wealth distribution and occupational structure develop over time at the village level. They thus describe village-level poverty traps.

In villages that have stayed poor throughout history there may thus be multiple constraints that will have to be handled. In the long run one may expect these to disappear as a result of structural transformation, but this may be generations down the road. Recent empirical research has demonstrated that big-push multifaceted graduation programs can lift these villages out of poverty, as discussed above. We will now go into more detail on some of the program components. The discussion will be organized around different types of market distortions. We have already discussed subsistence constraints, where people are not even able to repay loans. But there may also be other reasons why the credit market is not well-functioning.

6.3 Credit market imperfections

We have already discussed how lenders may be reluctant to lend to borrowers who have no collateral. This is because borrowers know themselves better than the lenders do. As a result lenders may end up lending to people who are less successful than they pretend to be (they hide their type), or people who put in less effort than what they say (they hide their actions). The borrowers may end up with unsuccessful businesses and without collateral they will not repay their loans. Knowing this, lenders will be reluctant to lend in the first place, and since they do not know who have less talent for business, or who will shirk, all potential borrowers will be hit by less access to capital.

In remote villages, lenders may be better informed and have alternative ways to collect the money. But each lender is likely to control only parts of the market, so that there may be a fragmented oligopoly where a small numbers of lenders may operate in multiple markets (Basu and Bell, 1991), or there may be a few lenders who control the same segment (Hatlebakk, 2009). In this case there is asymmetric information in the particular sense that borrowers and some few lenders are fully informed, while outsiders are not able to enter the market due to lack of information. The oligopoly of lenders will be able to charge interest rates above their cost. We shall thus expect to find oligopoly pricing in remote villages, and under-provision due to asymmetric information elsewhere, in addition to collateralized loans for the more wealthy borrowers.

Our main concern here is with the remote villages, where we are likely to find oligopolies of moneylenders, with some of them potentially being neighbors, friends and relatives. Many of the loans taken will initially be short-term. People take loans in the low season when there is limited demand for labor and limited availability of food. Many will repay after the harvest, some months later, paying quite often 5% interest per month. Some may, however, be hit by a negative shock, a main income earner may for example fall ill, and as a consequence they are not able to repay the loan. In that case, the loan will accumulate and they may end up in a debt trap. The latter can lead to bonded-type of labor contracts, where the family may have to work for the lender, even for years, to repay the loan (Genicot, 2002; Bose, Compton, and Basu, 2020).

Similar to the subsistence constraint, an asset transfer may solve the problem as the asset can be used as collateral. For small consumption loans, the normal collateral in villages will be jewelry, or simply gold, which can be collected if the borrower does not repay. It is hard to imagine that development agencies will provide gold to the poor, and micro-credit loans are normally considered an alternative. These may not require a collateral, and may break up the collusion among informal moneylenders. We will discuss this in more detail below. For agricultural production loans, let us say for livestock or small machinery, the asset itself will be a collateral, so that there may not be a market distortion. The market for this type of loans may, however, be slim, as the transaction costs of collecting animals or machinery in case of default can be high. So, again, micro-credit is an alternative.

Land is a special case. One may imagine that a Land Bank, or an Agricultural Development Bank, gives loans to buy land, against the land itself as collateral. This would allow smallholders and tenants to accumulate land. Still this form of credit is not widespread. In some countries this may be due to the widespread use of communal land, where farmers get the user right to land from the local authorities, at a relatively low cost. In this situation formalization may not be useful, as farmers already have the right to land, although carefully designed tenure reforms may secure land rights, and thus lead to more investments. But even in South-Asia, where private property rights, and land registers, are common, credit to purchase land is not widespread. Agricultural development banks have been providing credit against land as a collateral for decades, but these loans will normally require that the borrower already owns the land. It may be the case that potential sellers of land are more interested in selling for commercial purposes, or to larger landowners, than to tenants and smallholders who need government credit to purchase the land. Agricultural development banks, or commercial banks that by government regulation will have to serve marginal communities, may consider developing loan products where they give loans against purchased land as collateral. But let us now return to the issue of micro-credit, which has developed as a main instrument to solve credit market imperfections among the poor.

6.4 Micro-credit as a potential solution

Micro-credit was introduced as an alternative for poor people who do not have collateral to raise normal loans. The first selling point was joint liability within groups of borrowers. The assumption was that people self-selected into groups they knew well and thus expected to be able to repay their loans. The groups may be important, but not in the strict sense that borrowers default and then the others have to take over the responsibility for the loan. Instead group members, or members of adjacent groups, help people with the weekly installments when needed. Strict group liability is now replaced by individual liability in many micro-credit institutions. But there are other characteristics that contribute to the low default rate. Most likely a main explanation is the relatively small installments that take place during the weekly meetings in the normally all-female groups. Families may feel embarrassed if their mother, sister or wife cannot bring the necessary funds to the center meeting. And it has also been argued that weekly payments fit better with the income stream of the petty trading that normally is financed by micro-loans. Thus the installment schedule in combination with peer pressure seem to explain the low default rate.

Micro-credit loans will normally be only one of many loans taken by a family. They may have some old loans from a government bank that they do not intend to repay, maybe a commercial bank loan or two, and normally small, and potentially larger, loans from the informal market. Some of the latter may be taken only to strengthen their relation to more powerful people in the village: if a credit-line is established, you may be able to raise loans in time of need. Since money is fungible, and there may be other loans as well as many different ways of spending money, it is in many cases not feasible to say how the micro-loan is spent. The micro-credit institution may, however, require that the purpose should be business. As a result, many women will report petty trading. Since the micro-loans are in fact micro, and some of many loans, with large shares of the funding financing consumption and house repairs, one shall not expect to find large impacts on investments and income growth. This does not mean that they are not welfare-improving. People would not take up a loan unless there were some benefits, with replacement of more expensive informal loans being an obvious candidate. We shall, however, not expect these loans to be transformative as is now documented (Banerjee, Karlan and Zinman, 2015). They may still be an important element of a package of interventions to pull people out of poverty, as discussed above. But micro-credit will normally not be sufficient in itself when it comes to food security: when in need people will tend to rely on other (informal) credit sources, and the weekly repayment schedule is not tailor-made to agricultural investments.

6.5 Human capital

Above we have seen how subsistence income and credit market imperfections hinder investments among the poor, with a focus on physical capital. Under-investment is potentially an even larger problem when it comes to human capital. For most people human capital is a core determinant of income (Peet, Fink and Fawzi, 2015), also for smallholders with no or limited schooling. Even a few years of schooling will improve the numeracy and literary skills needed in many jobs. Investments in human capital have, however, uncertain returns for the individual, possibly far into the future: you go to school as a child, and, if lucky, this will help you get into better schools as an adolescent, which in turn, with even more luck, leads to well paid jobs. Parents may spend their full life working in low-skilled jobs to be able to educate a single child. With such a long horizon, and much uncertainty, we can be far from sure that people make the best decisions for themselves. Adding to this, people compete for the same jobs, and employers use the years of education as a screening mechanism to identify talented and hard-working candidates, even if the education in itself may not add much value. Thus for the society at large there is a coordination problem, with schooling potentially being a very costly screening mechanism. In societies where families take a large share of the costs, we shall expect that the less talented, but wealthy, over-invest in education. Thus there are strong arguments for prohibiting, or regulating, private schooling, and strengthening public schools to reduce the demand for private schooling.

For poor households the main cost of sending children to school is, however, not necessarily the direct costs of school fees and uniforms, but rather the alternative use of children’s time as they may otherwise be engaged in farm and household work. Thus for them to be able to compete on equal terms, some support beyond free schooling may be needed. Such cash transfers, conditioned on sending children to school, are found to be effective, but only if the conditions are really enforced (Baird, Ferreira, Özler and Woolcock, 2014).

6.6 Basic health and nutrition

A healthy body is the most basic human capital and important for many poor people, who depend on hard manual labor. They may not get sufficient nutrients to do their daily work, which for the majority of the poor will be farm work. One review concluded: “At least for malnourished populations ... the effects of improved nutrition may compare favorably with the effects of increased years of schooling” (Behrman, 1993). A seminal study noted the difference between the short term, where the laborer may be able to work hard despite low food intake, and the medium-term measure of underweight, that is reflected in low labor productivity (Deolalikar, 1988). The long-term measure of malnutrition, stunting, which is affected even by nutrition during mother’s pregnancy, is found to have long term economic consequences.

Food intake is thus necessary but not sufficient, the body has to be able to utilize the nutrients, with poor health potentially being a more critical factor than food intake (Deaton, 2013, in particular page 92 onwards). Beyond the direct effects on human welfare and productivity, poor health may also hinder uptake and utilization of nutrients in the body. Thus water facilities, sanitation and health services ranging from home visits, via dispensaries and village health centers to specialized hospitals will be essential for food security (see chapter three in Deaton, 2013, for a detailed discussion of the role of broad based public health measures and their interactions with nutrition).

6.7 Agriculture specific knowledge

We have thus far discussed basic education and access to health services as minimum standards of human capital that are necessary for productivity growth, including in agriculture. There is, however, also a need for more specific knowledge, in our case smallholder specific knowledge: productivity growth is needed for higher incomes, and thus access to food and other necessities, as well as availability of food for a growing population. For the majority of the poor, who are smallholders, increased productivity has a direct effect either as they can themselves eat what they produce, or in terms of higher incomes:

“Increasing production of staple grains ... has led to dramatic decreases in poverty, hunger, and mortality, particularly for the poorest and most vulnerable. Not only does increased smallholder productivity lead to improved outcomes for farmers and farmworkers, it also benefits food consumers, as it reduces staple food prices from increased production.”

From the third paragraph of the introduction: Jain, Barrett, Solomon and Ghezzi-Kopel (2023)

With most of the poor depending on smallholder agriculture, the transition out of poverty will go faster if this sector is prioritized.

Most African smallholders depend on rainfed agriculture (Sheahan and Barrett, 2017). Sheahan and Barrett find that irrigation, fertilizers and improved seeds are rarely used on the same plot, despite that this would, in theory, have strong synergies. Irrigation is, however, the critical factor, and only a small fraction of cultivated area is equipped for irrigation (You et al., 2011). It is thus essential to develop soil-management systems that are tailor-made to mostly rainfed agriculture, where fertilizers are supplemented with micronutrients and traditional soil management systems (Barrett and Bevis, 2015). The best mix will vary with local growing conditions and will require extensive collaboration between international agricultural research institutes, local research stations, extension services, and model farmers at the village level (de Janvry et al., 2016).

This means that techniques that may appear effective in one context will not necessarily be so in another, and local farmers are better placed to judge this than development agencies and even extension workers. It is essential that researchers and extension services work closely with local farmers to adjust new techniques to local conditions (Takahashi, Muraoka and Otsuka, 2020). In the process one should be aware that poverty itself is a constraint, as poor people cannot always afford to make risky decisions. Even if a new technique, for example the system of rice intensification (SRI), may lead to larger surplus on average, the higher risk of a bad harvest may hinder uptake of new techniques among the poor (Barrett et al., 2004).

SRI is still, however, considered as one of the more promising new technologies together with improved plants (cultivars), such as drought tolerant maize and flood tolerant rice that consistently improve productivity, and push-pull intercropping in maize (Jain, Barrett, Solomon and Ghezzi-Kopel, 2023).

6.7.1 Finding effective interventions

Since farmers themselves tend to be better informed than researchers (and development agencies) it is not straightforward to develop interventions that improve their knowledge and ultimately production decisions. There will be many factors that affect the uptake of new agricultural techniques that are outside the control of researchers and policy makers attempting to develop useful interventions based on available data. Farmers adjust to new techniques, potentially increasing the use of other inputs that would have alternative use in other income generating activities, such as labor efforts, but also inputs or efforts that will be unobservable for the outside observer. Any impact analysis should thus ideally measure not only the increase in yields or agricultural profits, but also changes in other incomes and welfare generating activities, including child care and leisure.

Randomized trials are quite common in agricultural research, but tend to have a limited scope, focusing for example on the increase in yields generated by some new invention, let us say new seeds. More recent RCTs may measure additional outcomes, taking into account behavioral changes that affect other economic activities. But we know that there are additional measurement problems, including spillovers, general equilibrium effects, or lack thereof in the case of small interventions, and adjustments to the research project itself for example by adjustments to the expectations from those who support the research financially or administratively: placebo effects are well known from medical research, but may also exist in social science experiments. In some RCTs one may add a relatively neutral intervention and measure the placebo effect by comparing the impact of this to no intervention. Information campaigns will regularly have a “neutral” alternative as the placebo treatment. But even a visit by a survey team, which may be needed to measure outcomes even for the no-intervention group, can have impacts on behavior.

An alternative is to use data from general purpose surveys, or even register data, that clearly are not linked to the intervention of interest. This may be combined with randomized interventions, but would then normally be interventions that affect large populations so that the survey will be considered as a general purpose survey. The first wave of RCTs, conducted in the 1960s and 70s, were of this kind (de Souza Leão and Eyal, 2020), although these early RCTs also had their problems (Heckman, 2020). Another alternative is to utilize natural experiments, or try to adjust for the selection bias that follow any non-random intervention, by identifying an appropriate control group.

The latter is, as we know, problematic since the smallholders who pick up new techniques will tend to be more successful even with existing techniques. Implementers can in fact utilize this, and use the more successful farmers as agents in spreading knowledge, as we will see in the next section. The spread of knowledge by such model farmers, or by peers, will be an intervention in itself, but with the added complexity that the rest of the group is no longer your average farmer, but rather those who are not considered as model farmers. Or, in the case of peer learning, one has to be particularly careful in estimation to avoid the so-called reflection problem where the behavior of one farmer is “explained” by the behavior of the group of farmers where he/she belongs (Manski, 1993). Acknowledging these methodological challenges, where many are not particular to learning, we now turn to some insights from research on learning among smallholders.

6.7.2 What type of learning works among smallholders?

Smallholders may copy production practices they observe are profitable at neighbors’ farms. This can be simple investments in livestock, small changes in growing techniques or input use, or small investments in machinery. The government may help with trials and dissemination of findings, in addition to providing assets. This was successful during the green revolution in South-Asia (Carter, Laajaj and Yang, 2021), and smallholder programs appear to have been successful in some African countries.

There are in principle four ways of learning new farming practices among smallholders: one can learn from neighbors or other peers, from extension workers, from model farmers trained by for example extension workers, and from different forms of public broadcasting. de Janvry et al. (2016, page nine, last paragraph) discuss some of the early programs where selected farmers were trained and in turn were supposed to train others. They conclude that these early programs were not effective. But they also report on successful program elements (page 10): select demonstration farmers as entry points, and give them incentives to actively share information, with learning taking place in conditions as near real-life as possible. de Janvry et al. (2017) go in more detail on the learning process and includes a number of case studies. The conclusions are similar: one should select demonstration, or contact, farmers as entry point for diffusion of knowledge, but allowing for a wide range of such entry points depending on the local context (de Janvry et al., 2017, page 10).

In the same collection, in chapter one (page 18), Sadoulet discusses what farmers may learn: in the simplest case it may just be knowledge about a new technique, but in reality they also need to learn whether the technique will fit in their particular case, subject to the other inputs needed and the constraints they meet. In learning what works, they will have only limited information regarding the underlying true relation between the efforts and inputs they use on the farm and the ultimate net incomes. Sadoulet presents a number of variations on learning models used in the literature, ranging from simple copying behavior to advanced learning of the underlying production relations when both production and information reflecting the underlying production relations are stochastic. She concludes the review: “A key unresolved issue is how to deal with heterogeneity in benefits. What value does a signal have if it is biased, and the extent of the bias is unknown? Are some outcomes less heterogeneous than others, and hence more amenable to be usefully transmitted in networks?”

And not only the profitability of new techniques is uncertain and heterogenous, also on the design of learning programs there are unresolved issues according to Sadoulet: “Who should generate the information/signals on what is to be learned? This is the key question of the choice of optimal injection points in social networks that would maximize the diffusion of the new technology. .... when signals have to be generated .... the quality of the person as experimenter also matters. The best experimenters are those that generate the most useful information for the others. Are they the best farmers, the median farmers, etc.?”

Subject to the underlying complex optimization problem that farmers face, which vary between them, one may wonder what external actors, including extension workers, researchers and development agencies, may contribute. The best approach may be to demonstrate what seems to work on similar farms, and then leave it to the farmers themselves to experiment with new techniques.

These techniques are more or less public goods in the sense that the use at one farm will not hinder other farms using the same technique, although the benefits may vary between farms. As for all public goods, there will be under-provision in unregulated markets, and thus a need for government support to R&D and extension services that takes into account that the benefits will vary between locations, and even between farms: it is thus a need for very localized R&D that is tailormade to the local context. Furthermore, extension workers may help farmers utilizing the knowledge, but only if they are able to adjust to each farmer’s needs. This is covered in chapter six of the same collection (de Janvry et al., 2017, page 71 onwards).

The authors find that extension services have not performed well historically, and should take better into account how farmers learn and adjust the learning process to local, and even farm-specific, conditions. This will require that extension workers collaborate with farmers so that one learns from previous experiences on own farm, as well as the experiences of similar farmers, and how they adjust to their own changing circumstances (page 80). They suggest a diverse strategy in selecting intermediaries between extension workers and farmers: if one expects the effect to vary between farmers, then peer farmers can be used as the point of entry. But if the new technology is complex, and the relevance potentially hard to understand, then imitation of lead farmers may be a better approach. For this to work, the lead farmers may have to be de facto leaders, in the sense that others trust that they make good decisions. An alternative information channel, that the authors discuss, is farmer field days, which they find useful. But they recommend involvement of farmer organizations, such as self-help-groups, when trust is necessary for farmers to take up new techniques.

The general conclusion is thus that there are promising techniques that can improve smallholder production, but only if adjusted to local circumstances, even down to the farm level. Farmers know their own constraints and can learn by observing neighbors that meet similar constraints, who are themselves experimenting with new techniques that they may have learnt from extension workers or others who in turn may learn from local agricultural research stations, who learn from national and international research organizations.

6.8 General policies for food security

This far we have discussed policies that focus on people who are constrained by poverty: low permanent income means that the costs of a bad harvest take a larger toll than the benefits of a similar size good outcome. This implies that farmers take less risk and are less willing to invest than their wealthier neighbors. On top of this, lack of assets means that they are less likely to get a loan to finance investments, or finance consumption in case of a bad harvest. As discussed, some remedies are agricultural techniques that are less prone to negative shocks, and to help people with assets and other social safety nets, microfinance, and different forms of human capital, including training and basic education.

We now move on from interventions that are intended to reduce poverty among the majority of poor people, who are smallholders, and turn to more general interventions that are relevant for all farmers, such as general R&D, infrastructure and other public services that may contribute to better food security. With government resources being limited, there may however be a conflict between policies that target the poor, and general policies that intend to fix market failures or policies that just favor some particular group, such as commercial farmers, marginalized social groups, or some other group favored by those in power. Examples are agricultural finance and R&D activities: shall governments prioritize large-scale commercial farming, potentially at the cost of driving up land and other input prices, or focus on policies targeting smallholders?

If large-scale farming is profitable, we shall expect the private market to provide the necessary finance, including some financing of R&D. But since R&D potentially may benefit all farmers, and not only those who bear the costs, there will be under-provision in private markets. This is the case for techniques that favor the poor as well as the wealthy, although less so for the wealthy since they can more easily afford investments themselves. Public R&D efforts should thus favor smallholders since they face additional constraints. But since positive externalities exist for all, there are arguments for a divided support. Adjustments to local contexts may however be less important for commercial farming, since commercial investors to a larger extent will have location as one of the factors they control, while smallholders are found basically everywhere, in all forms of local contexts.

Similar to R&D activities that may have positive externalities, public goods will also tend to lack funding, in particular if they are pure public goods where access cannot be restricted, and thus user fees hard to collect. Adding up market failures and lack of income, poor societies will tend to have many under-funded amenities, including public transportation, electricity and roads, and lack of funding may also limit investments in human capital, in particular basic education and health services, all factors that are important both as inputs to agricultural production and for distribution of the produce: primary health facilities and child nutrition may in principle be as important for long-term agricultural productivity as microfinance or agricultural research stations. So not only may better smallholder productivity lead to more, and better, food availability and better nutrition, there may be a virtuous circle, with better nutrition leading to higher productivity (Alderman, Behrman and Puett, 2017; Behrman, 1993; Dasgupta, 1993; Deolalikar, 1988; McGovern, Krishna, Aguayo and Subramanian, 2017; Thomas and Frankenberg, 2002).

7. Main conclusions

Food insecurity is explained not by lack of food, but by lack of income to buy food. This is also the case for small-scale farmers. While large-scale farmers operate, in principle, as any other firm, small-scale farmers face a number of additional constraints, which imply a close link between smallholder productivity and food security: the majority of poor people are engaged in smallholder agriculture, although not necessarily full time. Despite being food producers they are more at risk of malnutrition than the majority of the urban population, who benefit from relatively well-functioning food markets. The rural poor, on the other hand, meet multiple constraints with poverty itself being a major one. Lack of income and assets are, of course, in itself major problems. But they also lead to additional constraints as the poor may not risk investments in better, but more risky, technology, and may also not be able to raise the funds needed for investments, including in human capital. With many poor people in a village, it also means that the aggregate demand is low, which also hinders development. And with low incomes there is no surplus for investments in public goods, so that necessary amenities are not well developed.

Such village-levels poverty traps require packages of interventions that include: assets, cash, credit, insurance, health services, basic education, training, roads and electricity, all necessary conditions for development of smallholder agriculture and rural development at large, and together these multifaceted programs have been shown to lead to long term development of remote villages. An essential element of these programs are investments in assets, R&D and training tailormade to rainfed smallholder agriculture, which is the only option in most villages of Sub-Saharan Africa. Increased production means higher incomes, and will allow smallholders to either keep more of their own produce, or sell it to buy other necessities.

References

Abdulai, A. (2000). Spatial price transmission and asymmetry in the Ghanaian maize market. Journal of Development Economics, 63(2), 327-349.

Acemoglu, D. and Angrist, J. (2000): How Large are the Social Returns to Education? Evidence from Compulsory Schooling Laws, in: Bernanke, B.S. and Rogoff, K.S. (eds). National Bureau of Economics. Macroeconomics Annual, MIT Press

Alderman, H., Behrman, J. R., and Puett, C. (2017). Big numbers about small children: estimating the economic benefits of addressing undernutrition. World Bank Research Observer, 32(1), 107-125.

Aleem, I. (1990). Imperfect information, screening, and the costs of informal lending: a study of a rural credit market in Pakistan. World Bank Economic Review, 4(3), 329-349.

Ameye, H. and De Weerdt, J. (2020). Child health across the rural–urban spectrum. World Development, 130, 104950.

Aryeetey, E. (2005). Informal finance for private sector development in Sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Microfinance/ESR Review, 7(1).

Aryeetey, E. and Udry, C. (1995). The characteristics of informal financial markets in Africa. African Economic Research Consortium, Nairobi, Kenya.

Ayaz, M. and Mughal, M. (2024). Farm Size and Productivity: The Role of Family Labor. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 72(2), 959-995.

Baird, S., Ferreira, F. H., Özler, B. and Woolcock, M. (2014). Conditional, unconditional and everything in between: a systematic review of the effects of cash transfer programmes on schooling outcomes. Journal of Development Effectiveness, 6(1), 1-43.

Balboni, C., Bandiera, O., Burgess, R., Ghatak, M. and Heil, A. (2022). Why do people stay poor?. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 137(2), 785-844.

Banerjee, A., Karlan, D., Osei, R., Trachtman, H. and Udry, C. (2022). Unpacking a multi-faceted program to build sustainable income for the very poor. Journal of Development Economics, 155, 102781.