Switches from quota- to non-quota seats: A comparative study of Tanzania and Uganda

The reserved-seat system in Tanzania and Uganda

Common obstacles to switches from reserved to open seats

Transfer from a quota seat to an open seat: Why is Tanzania’s model better than Uganda’s?

How to cite this publication:

Vibeke Wang and Mi Yung Yoon (2018). Switches from quota- to non-quota seats: A comparative study of Tanzania and Uganda. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI Brief 2018:2)

Reserved-seat quotas have been used worldwide as a measure to get more women in parliament. However, they are meant to be temporary until women can compete with men for open seats using their quota experience. The cases of Tanzania and Uganda show that the reserved-seat design is a crucial factor in enabling quota MPs to make switches from quota- to non-quota seats. We find that the Tanzanian model is superior to the Ugandan model in facilitating switches.

The reserved-seat system in Tanzania and Uganda

Tanzania and Uganda pioneered reserved-seat quotas in 1985 and 1989, respectively. Ever since, there has been a rapid spread of reserved-seat quotas for women in parliament in sub-Saharan Africa.

However, Tanzania and Uganda have used completely different methods to recruit reserved-seat MPs. In Tanzania, recruiting reserved-seat MPs is an internal process where the political parties make lists of reserved-seat candidates. Reserved seats are then proportionally distributed among the political parties that meet a 5% threshold of popular votes in the parliamentary election. In other words, reserved-seat MPs are indirectly elected. In Uganda, one-woman representative is elected by universal suffrage in each district in directly contested ‘female candidate only’ elections.

The number of reserved seats has gradually increased over time in both countries, contributing to the increases in the total number of female constituency MPs. Currently, Tanzania reserves 113 of 393 parliamentary seats and Uganda reserves 112 of 427 parliamentary seats for women. However, reserved seats were never meant to be permanent. They were established as a temporary strategy until women could compete on their own with men for open seats. Which temporary strategy, then, is more efficient in enabling quota MPs to switch to non-quota seats?

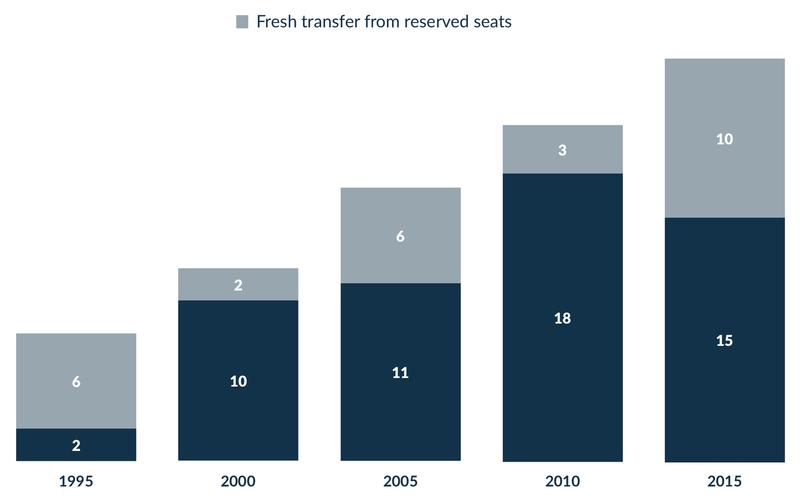

Figures 1 and 2 show the number of female constituency MPs in each country by election year, including ‘fresh switches’ from quota seats to open seats. The total number of fresh switches in Tanzania and Uganda suggests that the Tanzanian model is better in facilitating switches. The linear increase in the number of female constituency MPs (from 8 to 25) in Tanzania (Figure 1) is due mainly to the movement of some reserved-seat MPs to constituency seats in subsequent elections. Some female MPs have also been reelected in constituencies after the switch. Thus, ‘old and new switches’ together account for more than 50% of female constituency MPs in Tanzania.

This is not the case in Uganda (Figure 2) – where the number of female constituency MPs has vacillated, reaching a peak of 18 female MPs in the most recent election. The reserved-seat design each country uses is the decisive factor contributing to this difference, in combination with executive and ruling party pressure (or lack thereof) on quota MPs to switch to open seats.

Common obstacles to switches from reserved to open seats

Despite the increase in the number of female candidates and reserved seats, the number of switches to open seats has been small in both countries. Although the reserved-seat experience has given quota MPs an opportunity to show their talent and skills and has helped them build confidence and name recognition, they still face considerable obstacles when contesting for an open seat.

First, the competition for open seats is fiercer than for reserved seats. Thus, female candidates are at greater risk of losing the election than when contesting for reserved seats. Particularly, female candidates of the major parties often lose in party primaries where the competition is stiffer than in inter-party competition.

Second, the male-dominated culture, which shapes the view that women cannot be leaders, challenges quota MPs’ endeavors to become constituency MPs. They need to defy deeply engrained attitudes about their ability (as women) to suitably represent a constituency, as well as concerns that an MP needs to have been born in the area she or he represents (married women frequently move from their home area when they marry). Female candidates also experience a media bias; the portrayal of female politicians in the media is typically riddled with stereotypes.

Third, rampant election violence and intimidation – often with a gendered dimension – makes it difficult for women to seek an open seat. A former female open-seat MP in Uganda highlighted the sexual violence and insecurity during election campaigns saying, ‘Some of your political opponents can cut you and rape you just to embarrass you. So there are so many security risks involved with a woman campaigning and being exposed in this political environment’. In the case of Tanzania, female candidates do not encounter much physical violence, but still experience verbal abuse and intimidation from their male competitors.

Fourth, considering that candidates have to fund their own campaigns, women are financially disadvantaged compared to their male counterparts, because they have less access to patronage and independent resources. Many cannot afford the hand-outs to voters, contributions to formal and informal community projects, payments to campaign teams, transportation, and entertainment, which are important to gain votes. Opposition candidates, who do not have the ruling party machinery and party coffers to fall back on, are further disadvantaged.

Fifth, some obstacles quota women face are the result of the very system that brought them to the parliament. Specifically, the reserved-seat system can create the impression that women have their own seats. A former district MP and minister in Uganda, points to the discriminato onstituency] seats belong to men. Only the affirmative action seats are for women’. The system has also generated a view that there is a two-tiered system of legislators, and quota MPs are at risk of becoming second-rate representatives. Many quota MPs in both countries expressed the feeling that their colleagues and people outside of parliament do not give them the same level of respect as constituency MPs.

Furthermore, quota MPs, who serve a region or district, lack an electoral base. Though they are expected to attend to the needs of constituents in an entire region or district, they do not necessarily ‘belong’ to a particular constituency. Moreover, despite their in many cases wider areal coverage, they receive the same salaries and allowances as constituency MPs.

Transfer from a quota seat to an open seat: Why is Tanzania’s model better than Uganda’s?

Our interviewees (MPs and women’s activists) in both Tanzania and Uganda believe that women’s political space will expand if more quota MPs move to constituency seats and leave their quota seats to newcomers to politics. However, contrary to this expectation, many quota MPs, who face no term limits, continue to reenter the legislature as quota MPs. Only a small number of quota MPs have attempted to switch. Why, then, do some quota MPs choose to vie for open seats despite the hindrances? Ironically, the obstacles the quota system creates motivate some quota MPs to switch. First, they object to the perception that they are second-class MPs. A former Ugandan quota MP who successfully switched to an open seat stated, ‘Everywhere I would go, constituents would ask me “where is our MP?”’ Furthermore, in both countries, reserved-seat MPs are expected to inform constituency MPs in their regions or districts whenever they visit their constituencies. When both the quota MP and the constituency MP are present at official or social functions, the constituency MP speaks first. Second, the wider areal coverage of quota MPs – coupled with their lack of resources – makes them feel overwhelmed and overstretched.

Though it is difficult for quota MPs to switch to open seats in both Tanzania and Uganda, quota MPs in Tanzania appear to be doing better than their counterparts in Uganda. Their switches to open seats have contributed to the increase in the number of female constituency MPs. Some women have been reelected in their constituencies multiple times since their switches, and most female constituency MPs in the Tanzanian parliament have the reserved-seat experience. However, in Uganda, hardly any district representatives have crossed over to open seats, although there was an increase in 2016.

The difference between the two countries mainly stems from their different reserved-seat mechanisms and executive and ruling parties’ efforts to encourage the switch to open seats. Unlike voters in Tanzania, who indirectly elect quota MPs, voters in Uganda directly elect both constituency and quota MPs. Uganda’s reserved-seat design, therefore, has shaped the popular belief that district (quota) seats are for women and constituency seats are for men, creating two largely separate electoral spheres for female and male candidates and setting the standard for how many female representatives are elected to parliament. Constituents commonly view district MPs aspiring for constituency seats as intruders into someone else’s territory. A district seat MP explained how a woman standing for an open seat faced hostile comments from constituents who insisted, ‘If a hen crows, just get a knife and slaughter the hen. [The] hen cannot crow’ – implying that only men should contest for open seats and speak up in public.

The gendered perception of constituency seats as men’s seats affects not only the quota MPs’ decisions to run for constituency seats, but also party nominations and the electorate’s voting decisions. It discourages district MPs, including most high-profile women in parliament, such as Uganda’s Speaker Rebecca Kadaga, from standing for constituency seats. All things considered, it does not make sense for district MPs to risk their parliamentary seats by attempting to switch over to constituency seats, which are much more difficult to win. In addition, the change from indirect to direct election of district MPs in 2005 may have contributed to the inclination of Ugandan district MPs to remain in ‘their’ seats, by enhancing the legitimacy of district seats. The stigma against district MPs in Uganda appears to be less prominent than that against reserved-seat MPs in Tanzania. The seemingly gender segregated electoral spheres in Uganda also create institutionalized opposition by party gatekeepers and other political elites against women interested in contesting for open seats. For example, when a ruling party female constituency MP was up for her second term, her constituency became a district (single-constituency district). The president and party leadership pressured her to run for the district seat so that a man could be placed in the constituency seat, but she did not give in and won her second term. According to Ugandan MPs, a woman with no district-seat experience may have a better chance at winning a constituency seat, due to voters’ negative attitudes towards crossovers. However, if quota MPs decide to run for constituency seats, they have a better chance of winning in newly created constituencies, where there is no incumbent. Of five switches in Uganda in 2016, two were made in new constituencies.

In Tanzania, where there is no separate universal election to elect special-seat MPs, constituency seats are not perceived as ‘men’s seats’, because the quota design does not generate a perception that one election is to elect men and the other is to elect women. As a result, crossovers appear to cause few objections. According to former special-seat MPs who have switched to constituency seats, voters are willing to vote for special-seat MPs with proven records of service in their communities during their tenure.

Encouragement for switches by the executive and ruling party also make the process easier. In Tanzania, there has been an expectation that experienced quota MPs will compete for constituency seats in future elections, leaving their quota seats for other women. CCM’s much debated term-limit policy for special-seat MPs up to two terms is a case in point. This pressure has been less pronounced, if not absent, in Uganda, where the quota system is highly politicized, and the incumbent regime clearly benefits from preserving the status quo. When there is no explicit push from above to encourage quota MPs to run for open seats, there are few incentives for quota MPs to make the leap or for predominantly male party gatekeepers to change their practices.

The importance of the reserved-seat design

The actual reserved-seat design is crucial for making crossovers from quota- to non-quota seats possible. Uganda’s reserved-seat mechanism ghettoizes quota MPs more than Tanzania’s, by creating a perception that constituency seats are for men and quota seats are for women. This gendered perception affects not only female MP’s decision to run for open seats but also party nominations and voters’ decisions. Therefore, our findings suggest that quota policies should take the various effects of quota designs on fostering switches from quota- to non-quota seats into consideration to generate sustainable representation of women in politics.

References

Ahikire, J. 2004. ‘Towards women’s effective participation in electoral processes: a review of the Ugandan experience’, Feminist Africa 3: 8-26.

Goetz, A.M. 2003. ‘The problem with patronage: constraints on women’s political effectiveness in Uganda’, in A.M. Goetz & S. Hassim, eds.

No Shortcuts to Power: African women in politics and policy making. London: Zed Books, 110-139.

Muriaas, R.L. & V. Wang. 2012. ‘Executive dominance and the politics of quota representation in Uganda’, Journal of Modern African Studies 50, 2: 309-338.

Tripp, A.M. 2000. Women and Politics in Uganda. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press.

Yoon, M.Y. 2008. ‘Special seats for women in the national legislature: the case of Tanzania’, Africa Today 55, 1: 60-86.