Protection of Civilians – Norway in the Security Council

Protection of Civilians and the Ethics of World Politics

The UN at War – Consequences for the Protection of Civilians

The Law, the Court and the Interests of Justice in Afghanistan

How to cite this publication:

Edited by Antonio De Lauri; with contributions from Salla Turunen, Astri Suhrke, Maria Gabrielsen Jumbert, Kristoffer Lidén, John Karlsrud (2021). Protection of Civilians – Norway in the Security Council. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI Report R 2021:01)

This report summarizes a policy seminar organized by the Norwegian Centre for Humanitarian Studies in December 2020. It briefly points out some of the key challenges and opportunities for Norway in the Security Council in the period 2021-2022, particularly in relation to the issue of the protection of civilians.

Introductory note

Maria Gabrielsen Jumbert, Peace Research Institute, Oslo

The protection of civilians (PoC) emerged as a key international concern in the late 1990s, mirroring an increase in the number of peacekeeping operations and humanitarian activities. While on the face of it an indisputable term which everyone can rally around, it has been much debated and discussed. A central question has been how to achieve effective protection in practice, amidst complex conflict settings and when mandates to protect civilians of different international actors are intertwined and potentially at odds with each other. PoC, as the overarching aim of various forms of international engagement, has also been debated in terms of how it should be understood: as legal protection first and foremost, or as physical protection, and in the immediate and/or in the longer term? As a policy objective it has been a key concern for Norway over many years and is now one of the priority areas for the country during its period in the UN Security Council (2021–2022).

Protection of Civilians and the Ethics of World Politics

Kristoffer Lidén, Peace Research Institute, Oslo

PoC is an overarching normative agenda with a transformative legal and political potential, echoing cosmopolitan aspirations in the ethics of world politics. In a narrower understanding, PoC can be seen as a limited, humanitarian issue to be considered while pursuing other political ends. In line with political realism, this narrow concept sees the broad agenda as unrealistically undermining conditional political support for PoC in the UN Security Council.

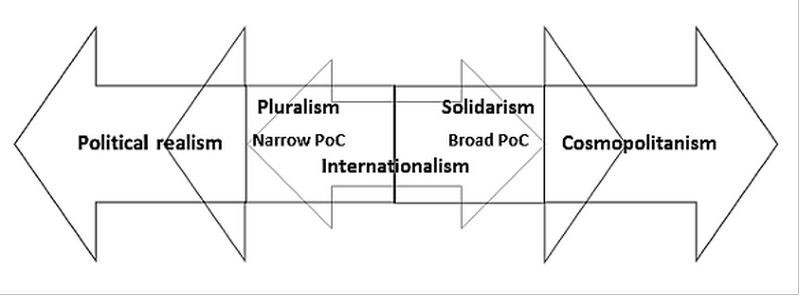

In practice, however, debates on concrete resolutions take place along a gradual scale in between the broad and narrow extremes. Hence, the question of PoC is not a question of political realism vs. radical cosmopolitanism but between different degrees of “internationalism” broadly defined. Retaining the role of the state as the main political actor and legal subject of international affairs, internationalism comes in many forms – from a pluralist rejection of any form of international political interference to a solidarist qualification of state sovereignty on a set of normative criteria such as the protection of human rights or – less demandingly – protection from mass atrocities. We may therefore place the debate on the scope of PoC within pluralist and solidarist versions of internationalism in the ethics of world politics (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Situating PoC in the ethics of world politics

The positions of the five permanent members of the Security Council can be placed along this scale, with France and the United Kingdom pushing for a solidarist approach and Russia and China insisting on a pluralist reading. The United States can be placed towards the middle, pragmatically supporting the solidarist approach in general while not committing to resolutions that constrain its own sovereignty or require military “humanitarian” intervention when conflicting with its self-interest.

The scale between pluralism and solidarism illustrates how PoC is not an either/or.[1] When PoC is defined broadly, the failure to enforce it in grave cases like Syria and Yemen may be taken as proof of its failure. However, most resolutions with a PoC component are passed with unanimous support. Without downplaying persistent problems, research indicates that UN-mandated PoC efforts generally have a positive effect. There is therefore room to advance the PoC agenda in spite of the lack of realism in its most solidarist versions. When aspiring to do so, Norway might take a strong solidarist position, perhaps even more consistently so than the UK and France, in an attempt to push the scale in a solidarist direction. This strategy may nonetheless backfire if it alienates its pluralist contenders. Hence, pragmatically building on limited support from Russia and China, an attempt to strike a productive balance between broad and narrow PoC seems to be the most effective strategy for Norway – although this may imply painful compromises with solidarist ideals.

The UN at War – Consequences for the Protection of Civilians

John Karlsrud, Norwegian Institute of International Affairs

PoC has been a staple ingredient in mandates for UN peacekeeping missions since first included in the mandate for the UN mission in Sierra Leone (UNAMSIL) in 1999. Since then, the understanding of PoC in UN peace operations has been deepened, conceptualised and enshrined in doctrine at strategic, operational and tactical levels.

However, there have been challenges. First, there has been the consistent challenge of translating policy into action, exemplified, for example, by the attacks on PoC sites in South Sudan in 2014, 2015 and 2016.[2] In 2014, an internal UN Office of Internal Oversight (OIOS) report found that, in 507 attacks between 2010 to 2013, peacekeepers rarely used force to protect civilians under attack.[3]

Second, humanitarian actors have argued that the UN, in spite of a nuanced conceptualization of PoC involving preventive as well as proactive measures, still resorts to a physical protection understanding of PoC.[4]

Third, there has been a trend towards peace enforcement in several UN peace operations since the UN mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO) was given a mandate to “neutralize” identified armed groups.[5] The turn towards peace enforcement may be motivated by a range of factors. Western member states have turned their attention to the UN, providing an influx of ideas, concepts and doctrine based on their engagements in Afghanistan and Iraq.[6] Concurrently, there has been increasing pressure from African member states that host UN peace operations for more robust mandates, including counter-terrorism.[7] The result has been mandates that task the UN to take direct action against identified groups – as seen with MONUSCO – and support ongoing counter-terrorism operations, as is the case for the UN mission in Mali (MINUSMA), tasked to support the Group of 5 Sahel operation. This severely impacts on the perception of the UN among local populations, and by extension the humanitarian community. The result is a more limited humanitarian space, and a restriction of the ability for conducting humanitarian action.

Unfortunately, there has been a widespread understanding among policymakers that it has been necessary to resort to peace enforcement mandates. But giving the task of protection of civilians under the Chapter VII mandate of UN peace operations gives ample leeway for robust action at the tactical level, without identifying the opponent who could be one of the main parties to the conflict:

- Robust peacekeeping involves the use of force at the tactical level with the authorization of the Security Council and consent of the host nation and/or the main parties to the conflict.

- By contrast, peace enforcement does not require the consent of the main parties and may involve the use of military force at the strategic or international level, which is normally prohibited for Member States under Article 2(4) of the Charter, unless authorized by the Security Council.[8]

Protection of Civilians and Humanitarian Diplomacy: How Operational and Policy Ends Influence One Another and How to Navigate this Relationship through Humanitarian Diplomacy

Salla Turunen, Chr. Michelsen Institute

Humanitarian diplomacy can be seen as closely related to “peace diplomacy,” which is a long-standing foreign policy tradition for Norway and a priority area for the country during the UN Security Council term. Humanitarian diplomacy, an instrument advancing humanitarian interests and goals by diplomatic means,[9] can play a key role in protecting civilians. Specifically, there are two central elements in relation to PoC from the perspective of humanitarian diplomacy: (1) the Security Council–field relationship as policy and operational ends, and (2) the inclusion of all stakeholders, even non-state armed groups.

Considering the former, the Security Council shapes the humanitarian operational context at the level of international diplomacy and politics. This has direct implications on PoC, for example, by directing policy attention to certain crises and mandating (continued) access to humanitarian aid and protection at state level. In July 2020, for instance, the UN Security Council Resolution 2533 considered humanitarian access through north-west Syria. However, the operational end also shapes and directs humanitarian diplomacy to a significant degree in field level implementation. At this level, policy aspirations and decisions balance with field negotiation and mediation, particularly access negotiations. These practitioner realities on the ground are heavily dictated by pragmatism, compromise, realism and feasibility. It is also at this level that national stakeholderships are embodied. Further, national grassroots level diplomatic encounters (such as humanitarian access negotiations) and politics shape the international context for possibilities and limitations in civilian protection, formulating a two-way channel of influence between the Security Council and the operational field.

Regarding the second element, humanitarian diplomacy is a key tool for multiple stakeholders’ inclusion. This is relevant due to the fact that in the majority of cases, armed groups control the territories where civilians with protection needs are located. According to data from the World Bank (2020),[10] approximately 80 per cent of the world’s humanitarian needs are driven by conflict. In this landscape, lessons can be learnt from humanitarian diplomacy’s ability to include all relevant official and non-official stakeholders, even armed groups. The challenges in negotiating with these groups stem largely from the fact that they adhere to very different principles from those of the UN and other similar humanitarian actors. However, some of these obstacles can be overcome through, for example, coordination of different actors on the ground, building relationships and trust with the armed group in question as parties to conflict, and tapping into the interests of the armed groups, for example, by substituting a service which they provide to their constituency. Furthermore, leveraging third party relations, such as the UN Security Council, is an important option at an international level in creating legitimacy for negotiations with armed groups.

The Law, the Court and the Interests of Justice in Afghanistan

Astri Suhrke, Chr. Michelsen Institute

Ensuring legal accountability for grave breaches and serious violations of international humanitarian law (IHL) is critical to PoC in armed conflict. Legal sanctions represent a first line of defence by potentially deterring future violations. They represent a last line of defence for IHL by upholding standards of justice understood to reflect basic human values and the concept of humanity.

The UN Security Council has assigned itself an important role in this regard. It established the international criminal tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (1993) and Rwanda (1994), thereby bringing the world closer to a permanent international criminal court. The Council twice referred cases to the International Criminal Court (Darfur/Sudan 2005, and Libya 2011). Both referrals were controversial. Another case now before the ICC will probably reverberate in Council deliberations, but for quite different reasons.

The ICC recently authorized the Prosecutor to initiate formal investigation of war crimes and crimes against humanity that may have been committed in Afghanistan after 2003.[11] That includes investigation of acts committed by the US military and the CIA on Afghan territory and on “rendition sites” in Poland, Romania and Lithuania.[12] The Prosecutor aims to institute institutional criminal accountability for interrogation techniques amounting to torture, promising to investigate those who “developed, authorised or bore oversight responsibility” for these acts.

The ICC wheels of justice grind slowly. Formal indictments and arrest warrants – if issued – may be years in the future, and US officials are unlikely to be handed over to stand trial. Yet the matter raises important political and legal issues for friends and critics of the Court, for allies and adversaries of the US, and, for Norway, especially given its two-year seat on the Security Council.

The dilemmas are plain. A common criticism levied against the ICC has been its focus on cases in the South. The inclusion for the first time of high-level American officials as targets of investigation will give supporters of the Court and the rule of law a chance to stand up and be counted. On the other hand, it is a given that there would be staunch American opposition to such a stance and the near-certainty that even a long and costly investigation would not lead to the trial of American citizens. Which course of action, then, will serve “the interests of justice”?

Notes

[1] Lidén K. (2019) The Protection of Civilians and Ethics of Humanitarian Governance: Beyond Intervention and Resilience. Disasters 43(S2): S210-S229.

[2] Arensen M. (2016) If We Leave We Are Killed: Lessons Learned from South Sudan Protection of Civilians Sites 2013-2016. Juba: International Organization of Migration.

[3] UN General Assembly (2014) A/68/787. Evaluation of the Implementation and Results of Protection of Civilians Mandates in United Nations Peacekeeping Operations. Report of the Office of Internal Oversight Services. New York: United Nations General Assembly.

[4] de Carvalho B. and Sande Lie J.H. (2011) Chronicle of a Frustration Foretold? The Implementation of a Broad Protection Agenda in the United Nations. Journal of international Peacekeeping 15(3-4): 341–362.

[5] Karlsrud J. (2015) The UN at War: Examining the Consequences of Peace Enforcement Mandates for the UN Peacekeeping Operations in the CAR, the DRC and Mali. Third World Quarterly 36(1): 40–54.

[6] Karlsrud J. (2019) For the Greater Good? “Good states” Turning UN Peacekeeping towards Counterterrorism. International Journal 74(1): 65–83.

[7] Karlsrud J. (2019) From Liberal Peacebuilding to Stabilization and Counterterrorism. International Peacekeeping 26(1): 1–21.

[8] United Nations (2020) Principles of Peacekeeping. https://peacekeeping.un.org/en/principles-of-peacekeeping.

[9] Turunen S. (2020) Humanitarian Diplomatic Practices. The Hague Journal of Diplomacy 15(4): 456–487.

[10] The World Bank (2020) Fragility, Conflict and Violence: Overview. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/fragilityconflictviolence/overview.

[11] https://www.icc-cpi.int/afghanistan.

[12] https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/09/02/qa-international-criminal-court-and-united-states ; De Lauri, A. and Suhrke, A. (2020) Armed Governance: The Case of the CIA-Supported Afghan Militias. Small Wars and Insurgencies, https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09592318.2020.1777618.

Maria Gabrielsen Jumbert

Kristoffer Lidén

John Karlsrud

Research Network on Humanitarian Efforts