Sudan’s Me Too moment needs its own revolution

It is challenging to find a digital footprint for the conversation on Lil’Freeny, a Sudanese-American hiphop artist who was accused of sexual harassment through an anonymous story shared with MeTooSudan, a twitter page that has since gone offline after facing the threat of litigation. But screenshots are here to help us put the pieces of the story together.

Arabic version: السودان تحتاج ثورة المي تو(MeToo) الخاصة

The MeTooSudan page may have been forced to silence, but the stories shared with MeToo Sudan and the impact of sexual harassment and sexual assault on women are documented and told through these screenshots.

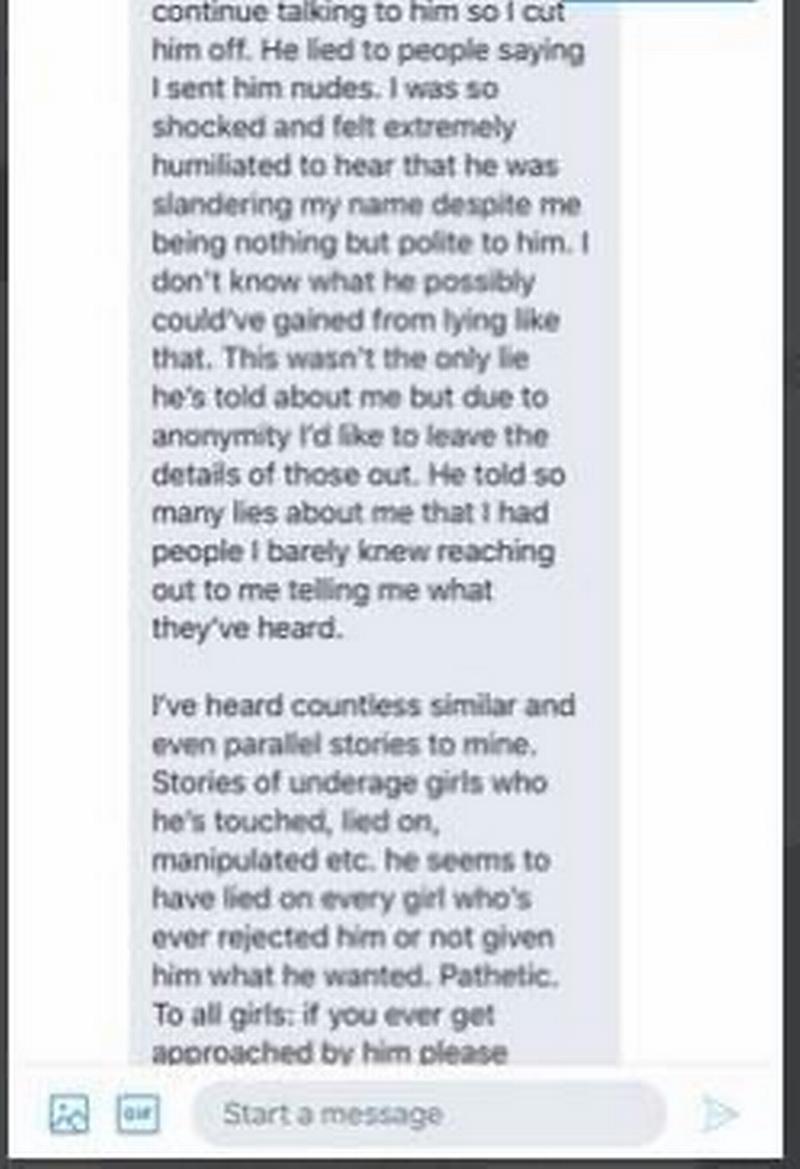

On July 1st, MeTooSudan published an account by a young woman who said that she was coming forward to speak about her encounter with Lil’Freeny because she had heard ‘stories of underage girls who he’s touched, lied about manipulated etc.’

According to the story, at the time of her encounter with him, she was 16 years old and he was over the legal age in the US . She accused him of harassment and then spreading rumors about her by telling people that she had sent him nudes. She saw this as an intention to tarnish her reputation.

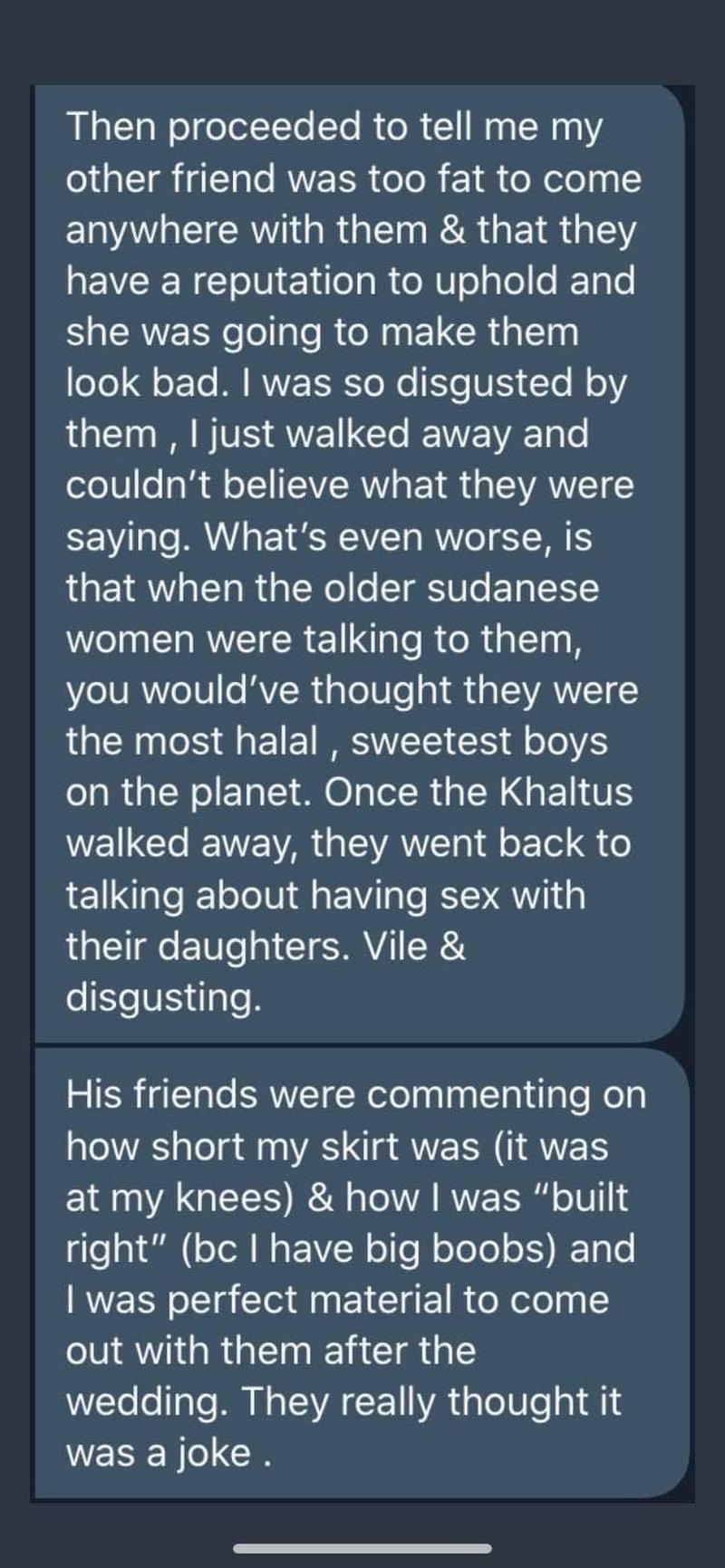

Other women came forward, albeit anonymously, and said that this destructive behavioral pattern is prevalent in Lil’Freeny’s circle.

When Lil’Freeny rose to fame in Sudan after releasing a single called Sam7a (which means beautiful in Sudanese colloquial Arabic) last year. The video was met with little scrutiny although some in my circle were quick to point out that some of the models seemed to be under-aged high school students. This information was never corroborated, but was brought up again when the testimonies about his behavior began circulating to prove his predatory behavior towards girls.

In the hours and days after this commotion unfolded, Lil’Freeny continued to further implicate himself.

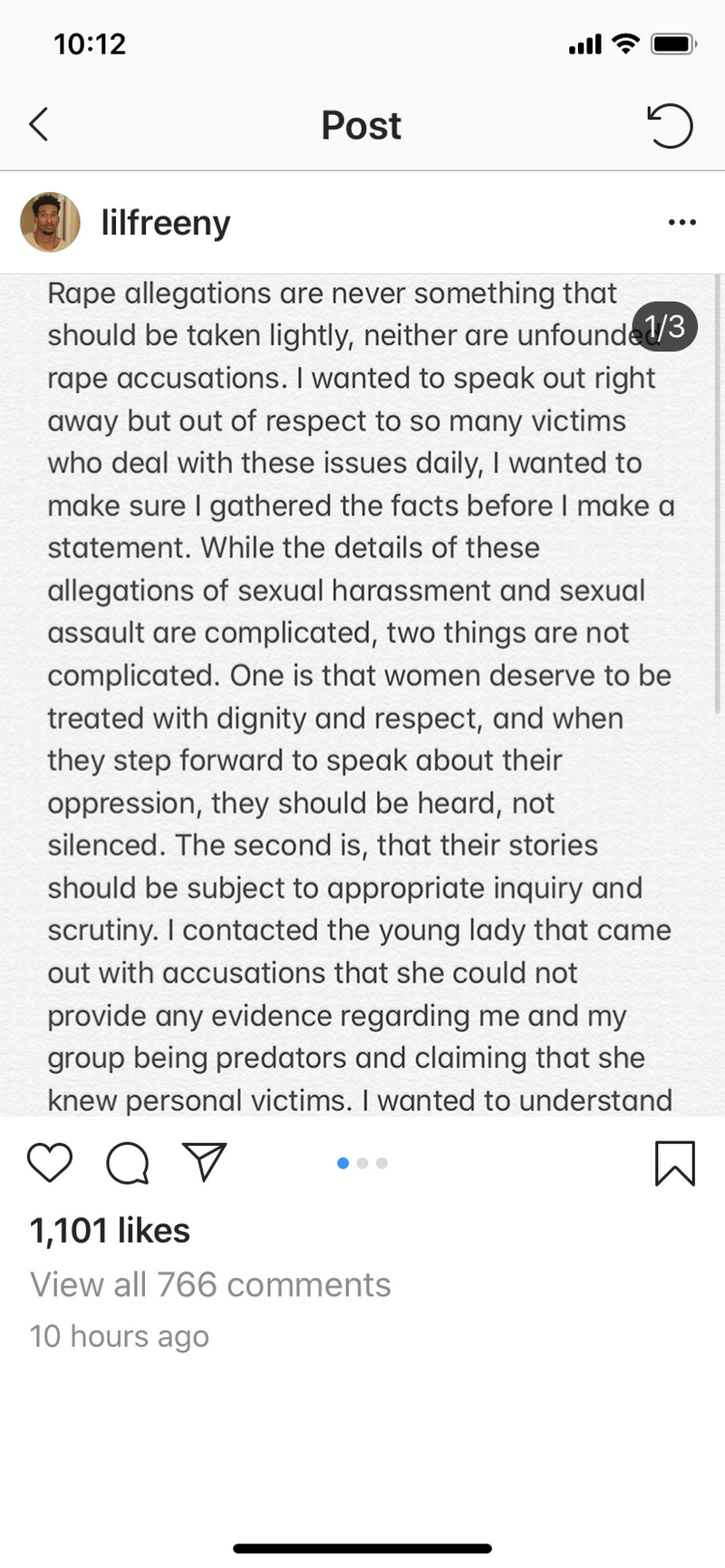

On July 2nd, he published an apology on his Instagram account. He started it by saying that ‘rape allegations are never something that should be taken lightly’. This further exacerbated the situation, as until that point, no testimony implied rape accusations. This strange apology began instigating suspicion that perhaps there were gaps in the viral testimonies or that there was a larger story that no-one was talking about.

It is also important to note that several people pointed out that his apology was nothing short of plagiarism. Under scrutiny, an entire paragraph in the apology is word by word taken from Joe Biden’s response to Tara Reade, a former Senate employee who has accused Biden of rape and another paragraph plagiarizes a tweet by Justin Bieber, a popular pop artist, written just ten days earlier. The apology post has since been deleted and it remains unclear whether it was taken down to avoid substantiating accusations and a possible lawsuit for plagiarism or because it started out by addressing ‘rape allegations’ that have not been made in the first place and could support the women if they chose to pursue a lawsuit.

As the tweets went viral, his group was trying to narrow down the ‘leakers’ and other potential testimonies. One young woman from the DMV- the Washington D.C., Maryland and Virginia area -where he lives- tweeted that his friends had called her mother.

Co-opters came to his defense and criticized the women for submitting anonymous stories and tried to use this fact to attack the credibility of the Sudan MeToo page thus questioning the credibility of the women themselves. Qutofy, a Sudanese activist and co-founder of an artistic platform called Locale commented that ‘the only way women know to protect themselves is to tell their stories anonymously. Men can be publicly accused and still be vocal and rallied behind because their accuser is anonymous. They’ve created the perfect system’.

As the twitter page gained followers, it started receiving and sharing numerous stories a day.Some of these stories disclosed well-known activists as sexual harassers. On the 2nd of July, an anonymous story accused two lawyers of sexual harassment.

This story was especially disappointing as both lawyers are involved in an investigation committee to bring justice to victims of killings and sexual violence at the hands of the Sudanese military junta and its militias.

To date, there has been no official statement by the committee or by its members to address those allegations and in the process, take part in the social media discussions centering on sexual harassment. Other activists and young political leaders were also outed by the twitter account which reminded people of the famous ‘out a harasser’ hashtag from 2019.

Ounaysa Arabi, a student at the university of Khartoum, a teacher and a women’s rights activist affiliated with the Noon movement for women shared a story using the ‘out a harraser’ or ‘ افضح متحرش “ hashtag last year to encourage women to share their stories and shame harassers who often feel protected.

When she identified a young politician as a sexual harasser and shared her own experience with him, hell broke loose.

She took her complaint to his political party, a liberal newly-established political party, and was told that ‘they will only take action once the court takes action on their case’ which is unfortunate because women rarely get justice in the courthouse in Sudan .

‘He shared a picture of a paper showing a headline emphasizing that it is from the cyber crimes prosecution to show that he filed a complaint against me for defamation, but I have yet to receive a subpoena or was summoned by the court’ said Arabi.

A few months later, the social media buzz around Arabi’s issue has settled, but the politician has since said that he wants to talk to her father.

‘He thinks because he is a man, he can just come to my father and speak about what had happened. I know what happened and I am not scared’ she commented.

The strength of the ‘perfect system’ created by men is that it discredits any narrative drawn by women and gives men control of the narrative and the justice system that should, in theory, give justice to victims and survivors. It also takes advantage of the patriarchal structure by not shying from bringing in a woman’s family and male relatives who often, grudgingly, take the wrong side of history.

Why didn’t she?

In 2016, an award-winning Sudanese journalist accused a journalist and member of the Sudanese Communist party of sexual harassment. After the incident, she wrote about it on Facebook and she also submitted a written complaint to the Communist party asking them to investigate her complaint and give her justice.

Following her complaint, a female member of the central committee sent her a message and told her that they had discussed the incident and that the party would apologize to her.

The apology never came through.

Four years later, she shared her Facebook ‘memory’ to remind people of the sexual harassment incident and commented on it. This unleashed a wave of anger at her. Critics questioned the timing and shamed her for not going to the police and filing a legal complaint when it happened and taking this matter to court instead of taking it to Facebook.

She argued that her only intention was to bring it up again because it had never been resolved in the first place. She never received a formal apology from the party or from the harasser. They let the case shrivel instead of using this as an opportunity to have a critical conversation about sexual harassment and work on a party policy on sexual harassment. It would not have been an unnatural move for them, as the journalist’s case was not the first to tarnish the party’s reputation for their dealings with sexual harassment. A prominent party member quit after a similar case only a few years ago. Her case was never properly resolved either.

I found it interesting how many of the comments scolded the journalist for not bringing the case to the court. The people behind the comments identified as political, human and even women’s rights activists.

However, there is a larger story. Women in Sudan don’t go to the police if they are sexually harassed and we shouldn’t pressure women to do it simply because they define themselves as feminists or women’s rights defenders. That is not what this is about. This is about the system they are up against. The article on sexual harassment in the 1991 Criminal Code criminalizes female harassment victims. Not even the legal reform in 2015 changed this. The vaguely defined article leaves it up to the police to determine what constitutes sexual harassment. This is clearly to women’s disadvantage in a system and society where women are regarded as hyper-sexual beings; if left uncontrolled they will commit immoral acts.

In fact, rights groups explain that the law is vague on distinguishing between victims and perpetrators as it refers to ‘ acts, speech or behavior that cause seduction or temptation’. They argue that this is a ‘further deterrent to women reporting sexual offences’. In fact, if women can’t prove sexual harassment, they could face charges of gross indecency.

Cases are usually killed at the first stage of reporting a case and you are usually advised against going through with it because it is tedious, the witnesses will not show up and of course your fragile reputation will surely be impacted. In the last few years, very few women have received justice on sexual harassment grounds. Instead they are blamed for the crime committed against them or in the words of Heba Tabidi, ‘we victim blame - reinstating this idea that it was you. You asked for it. Labsa shinu (what were you wearing?), kooti wien (where were you?), itkalemti keif (how did you speak?). What did you do to trigger this natural instinct within our men that is just a part of who they are?’

Days after the communist party member responded to the prominent journalist in a hurtful and demeaning way.The party has yet to comment on his claim; that her allegations were unfounded and mere lies.

He as well as Lil-Freeny remain under the protection of the system. Sometimes though, there is reason to feel encouraged. In a published statement, Young justus, a record label and media enterprise asked Lil’Freeny to remove their collaboration from his single ‘Sam7a’ and wrote that they reject ‘any actions of sexual assault, abuse or harassment against women and explicit condemn actions of sexual assault against minors’.

The controversy caused by a number of public cases and the MeTooSudan twitter account shows that Sudan doesn’t need a Me Too moment, it needs a full-blown revolution that starts by addressing how deeply entrenched exploitative and harassing behavior is within political, activist and creative circles, and that makes unrelenting actions to reform the judicial system and personnel and gives survivors platforms that are larger than twitter accounts.

This Sudan blog post is written by Reem Abbas, a freelance journalist, writer, researcher and communications professional. She tweets using @ReemWrites

The views expressed in this post are those of the author, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the ARUS project or CMI.