The future of UN policing? The Norway-led Specialized Police Team to combat Sexual and Gender-Based Violence in Haiti 2010–2019.

Peacekeeping in Haiti and the development of the Haitian National Police

Sexual and gender-based violence in Haiti

The Specialized Police Team on Sexual and Gender-based Violence

SGBV 1 (2010-2014): Professionalization and strengthening of operational capacity in the HNP

SGBV 2 (2015–2019): Developing the Unit to Combat Sexual Violence (ULCS) and further specialization.

Relevance, effectiveness, and sustainability of the SPT activities

The SGBV offices in the HNP Commissariats

The One Stop Center at Justinien Hospital

The Unit to Combat Sexual Violence (ULCS)

How to cite this publication:

Marianne Tøraasen (2021). The future of UN policing? The Norway-led Specialized Police Team to combat Sexual and Gender-Based Violence in Haiti 2010–2019.. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI Report 2021:3)

The purpose of the specialized police team deployed to Haiti under MINUSTAH was to help build the Haitian National Police’s capacity to prevent, investigate and prosecute SGBV, which had increased dramatically in the aftermath of the 2010 earthquake. Two years after the specialized police team’s departure, this report examines the relevance, effectiveness and sustainability of the team’s SGBV projects in Haiti.

List of abbreviations

BINUH United Nations Integrated Office in Haiti

DPKO/DPO Department of Peace Operations

HNP Haitian National Police

MINUSCA United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilizations Mission in the Central African Republic

MINUJUSTH United Nations Mission for Justice Support in Haiti

MINUSMA United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali

MINUSTAH United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti

MONUSCO United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

SGBV Sexual and gender-based violence

SPT Specialized Police Team

ULCS Unit to Combat Sexual Violence

UN United Nations

UNMISS United Nations Mission in the Republic of South Sudan

UNPOL United Nations Police

Summary

This report examines the Norway-headed specialized police team’s (SPT) projects on sexual and gender-based violence, deployed to the United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH) from 2010 to 2019. The focus is on the relevance, effectiveness and sustainability of the projects under the SPT. The overall aim of the SPT was to build the capacity of the Haitian National Police (HNP) to prevent, investigate and prosecute sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV). The prevalence of SGBV increased dramatically in the aftermath of the 2010 earthquake, and the HNP was not sufficiently prepared and equipped to combat it. At the time of deployment, specialized police teams were a new approach to UN policing in peacekeeping missions, and there existed little formal guidance on the team’s role. The experiences from the Norwegian-led specialized police team in Haiti hence helped inform the further conceptualization of SPTs, which are today becoming more frequent in UN policing in peacekeeping missions.

The SPT benefitted from having an earmarked budget for programming funded in its entirety by the government of Norway. During the first SGBV project (2010-2014), activities included extensive training of HNP personnel, implementing a SGBV course in the basic training of new cadets from the HNP School, and support the building/refurbishing and equipping dedicated SGBV offices in the HNP Commissariats all over the country. The expected outcome was a more professionalized HNP with stronger operational capacities. The second SGBV project (2015-2019) resulted in the creation of a specialized unit to combat SGBV, several workshops and seminars. Expected outcomes included a more professional, coordinated and harmonized response to SGBV investigation, among the HNP and other relevant actors.

Through interviews with key stakeholders and written sources, this study takes a closer look at the wider outcomes of the activities completed by the SPT, two years after the closure of the UN peacekeeping mission and the departure of the SPT. The SPT projects addressed important needs in the HNP and in Haitian society. Feedback from counterparts on the quality of services provided by the SGBV offices, and particularly the ULCS unit, signals that staff are competent in SGBV issues. They also reportedly treat victims who report cases with more care and less discriminatory attitudes than what is the norm among HNP. Still, the effectiveness of these specialized SGBV units is severely hampered by a lack of organized follow-up; no systematized registering of cases; and a lack of means needed to investigate cases and do awareness-raising, among other things. The sustainability of the efforts is also threatened by a lack of funding and follow-up: Several of the SGBV offices in Haiti’s regional departments have closed down, and all lack necessary equipment. The deteriorating economic and sociopolitical situation of Haiti threatens both the effectiveness and sustainability – and the future impact – of the SPT efforts, exemplified by how the Haitian National Police School have not managed to educate any new cadets since 2019. For future use of SPTs in UN peacekeeping missions, it is important to consider how activities will be sustained and monitored once completed, with regards to funding, follow-up, and collaborative UN partners still on the ground after the team’s departure. If not, one risks that the framework set up by the SPT will fade away.

Introduction

In the wake of the 2010 earthquake, sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) in Haiti increased dramatically. In response, Norway sent a specialized police team (SPT), deployed to the United Nations Stabilizations Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH). The aim was to build the capacity of the Haitian National Police (HNP) to prevent, investigate and prosecute sexual and gender-based violence. At the time of deployment, specialized police teams were a new approach to UN policing and there was little formal guidance on the role of SPTs. Until then, most police deployed to UN peacekeeping missions had been ‘individual police officers’ (IPOs) or members of ‘formed police units’ (FPUs). The Norwegian-led SPT in Haiti thus became a pilot project, and the experiences from this team formed the basis for the further conceptualization of specialized police teams in United Nations Peace Operations.

A specialized police team is defined as a multidisciplinary team of experts in a particular field of police work seconded by one or several UN Member States. SPTs provide operational support, capacity training, and development services to host-state counterparts in specialized police fields such as investigations, serious and organized crime, community-oriented policing, or SGBV. The SPT is deployed as a team of 2 to 15 police officers and civilian policing experts, usually for a period of 12 months. Today, SPTs are present in UN peacekeeping missions in Mali (MINUSMA), the Democratic Republic of the Congo (MONUSCO) South Sudan (UNMISS) and the Central African Republic (MINUSCA). According to the UN, the increased use of SPTs in peacekeeping missions reflects the growing demands from host-states for more specialized police expertise and operational support targeting specific capacity gaps in the local police and law enforcement. While UN peacekeeping missions normally control project money within their own budgets, SPTs are often deployed with their own project funding, which is meant to increase effectiveness. The Norwegian-led team in Haiti was fully funded by the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs with a budget of more than 15.5 million NOK in total and was hence the first SPT with their own funding earmarked for programming.

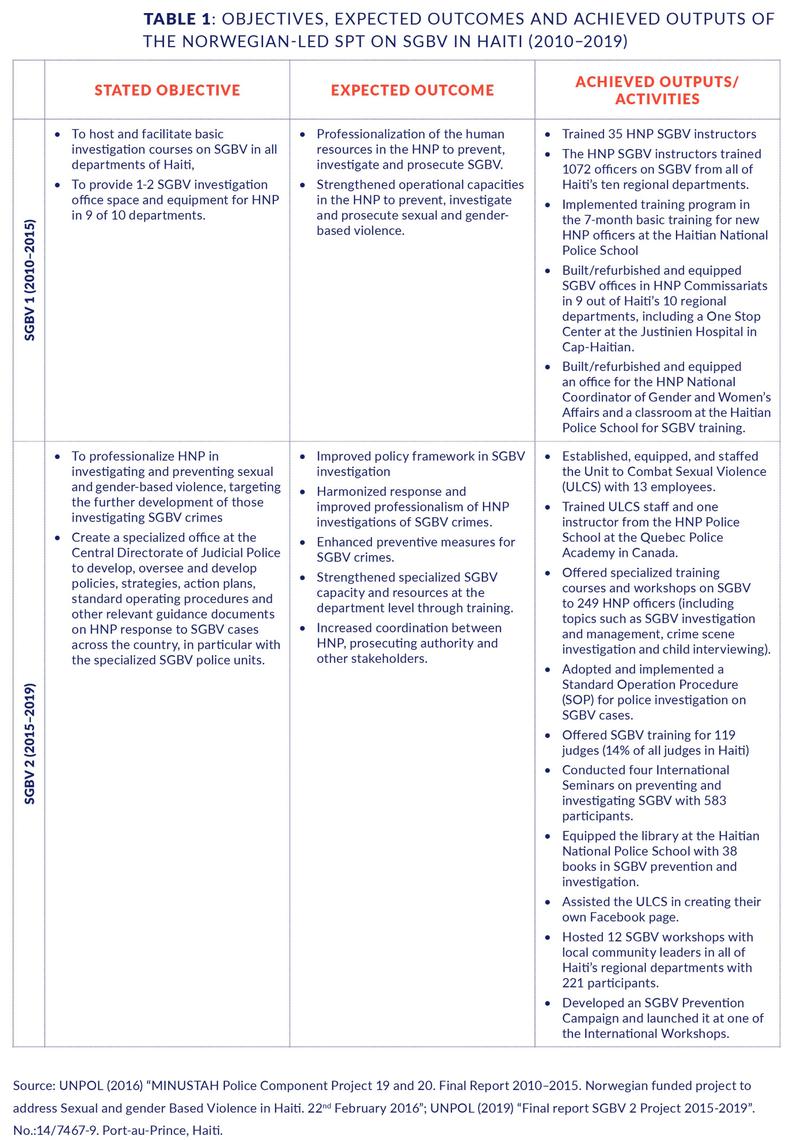

The main stated objective of the first SGBV project was to host and facilitate basic investigation courses on SGBV in all of Haiti’s departments and to provide SGBV investigation office space and equipment for HNP in 9 of 10 departments. The program aimed to contribute to the professionalization of human resources and strengthened operational capacities in the HNP to prevent, investigate and prosecute SGBV. The stated objective of the second SGBV project targeted more specifically the further development of those investigating SGBV cases and to support the creation of a specialized SGBV unit in the Central Directorate of Judicial Police (DCPJ), which would develop guidance documents on HNP response to SGBV cases and oversee and monitor its use across the country. The expected outcome was strengthened specialized SGBV capacity, enhanced preventive measures for SGBV crimes, and more harmonized approach to the investigation of SGBV crimes, involving cooperation with other justice actors. The list of outputs and activities achieved by the SPT is long, and includes training of around 1700 HNP officers, other justice actors and local community leaders on SGBV issues; introducing a one-week training course on SGBV for new cadets at the Haitian National Police School; refurbishing/building and equipping 13 dedicated SGBV offices in HNP Commissariats all over Haiti; and establishing a specialized SGBV unit charged with leading national work on SGBV investigation and prevention, just to mention some. For a total overview of the outputs, stated objectives and expected outcomes, see Table 1.

Based on these outputs, the Norway-led SPT was deemed a successful innovation and has been referred to as “the future of UN policing”. This report examines these activities in in greater detail, two years after the SPT members – and with them the dedicated funding – left Haiti. This follow-up approach helps assess to what extent the SPT has contributed to the anticipated outcome of a better, more professional, and harmonized approach to SGBV. To address this question, the report focuses on the relevance, effectiveness, and sustainability of the various SGBV projects led by the SPT in Haiti. As specialized police teams are becoming an increasingly used approach to UN policing with several teams currently deployed to UN peacekeeping missions, there are important lessons to learn from the SPT in Haiti.

Methodology

This study was conceived under a framework agreement between the Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI) and the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, established to provide relevant knowledge about Norwegian foreign policy and development assistance. Between January and June 2021, the author conducted semi-structured interviews with key informants, such as former SPT team members in Norway, the National Police Directorate in Norway, the UN police division, BINUH personnel, HNP officers, Haitian judges, and NGOs working on SGBV issues in Haiti. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, travel was restricted at the time of research. The interviews were thus conducted through Teams, WhatsApp, phone calls or e-mails, and in Norwegian, English and French. The author also draws on previous fieldwork in Haiti which included visits to the Unité de Lutte Contre les Crimes Sexuels (ULCS) – the Unit to Combat Sexual Violence in the capital Port-au-Prince, and interviews with numerous justice actors and women’s rights activists. In addition, the study draws extensively on project documents and reports from the various UN missions to Haiti, reports from the UNDPO, evaluation reports and final reports from the SPT projects and other team documentation.

The meanings of relevance, effectiveness and sustainability in this study is based on the evaluation criteria defined by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Development Assistance Committee (DAC) for assessing interventions in development work. Relevance is defined as “the extent to which the intervention objectives and design respond to beneficiaries’, global, country, and partner/institution needs, policies, and priorities, and continue to do so if circumstances change” and seeks to assess whether the intervention is “doing the right thing”. Effectiveness refers to “the extent to which the intervention achieved, or is expected to achieve, its objectives, and its results”, while also considering the relative importance of the different objectives or results. Sustainability refers to “the extent to which the net benefits of the intervention continue, or are likely to continue”, which includes “an examination of the financial, economic, social, environmental, and institutional capacities of the systems needed to sustain net benefits over time”. Impact (“the extent to which the intervention has generated or is expected to generate significant positive or negative, intended or unintended, higher-levels effects”) will only be briefly addressed, as too little time has passed since the end of the SGBV projects to detect its “ultimate significance and potentially transformative effects”.

Measuring effectiveness of the SPT outputs poses some challenges in the Haitian context. One way to measure effectiveness is through potential changes in reported SGBV cases. An increase in reported cases under investigation might reflect increased professionalization and operational capacities of the HNP regarding SGBV crimes. However, this approach has several weaknesses and challenges. Neither the Unit to Combat Sexual Violence (ULCS) in Port-au-Prince nor the SGBV offices in the HNP commissariats across the country could provide statistics for this study, reflecting the lack of systematized registration of SGBV and other crimes in Haiti. Using national statistics available in various UN reports do not allow for isolating the effects of the SPT initiatives from other initiatives on sexual and gender-based violence by various actors focusing on this issue, of which there are many in Haiti. The UN used to collect statistics manually from police stations across the country, but this has not been done systematically since the downscaling of the UN missions. Furthermore, when the UN headquarters collapsed in the 2010 earthquake, all statistics on SGBV were lost. There is thus no foundation for comparison prior to the SPT’s deployment in 2010. A more fruitful approach for this study will be to look specifically at the different initiatives made under the SPT’s direction, and to study their reach, use, and quality. Talking to NGOs and justice actors who works with victims of SGBV provides a valuable user perspective. One limitation to this approach is that my sample of NGOs only work in some parts of the country. However, their insights can give an important indicator of the effectiveness of the SPT’s efforts.

Peacekeeping in Haiti and the development of the Haitian National Police

Since the fall of the Duvalier dictatorship in 1986, Haiti has been stuck in a protracted and violent transition towards democracy, marked by political instability, coups, foreign intervention, natural disasters, extreme poverty, and an inability by fragile governments to provide basic services to its citizens. The United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH) was established in 2004. The authorization of MINUSTAH was prompted by widespread armed conflict and the second ousting of democratically elected President Jean-Bertrand Aristide. The MINUSTAH mandate was to restore and secure a stable environment, to protect and promote human rights and the political process, and to improve government institutions and the rule-of-law structures. A key goal was to professionalize the Haitian National Police (HNP) and prepare it for maintaining peace and security in the future.

The creation of a national police force was first envisaged in the post-authoritarian constitution of 1987. During the military coup (1991-1994), a special police unit of the armed forces (FAD’H) were responsible for policing. President Aristide demobilized the armed forces when he was elected president in 1994 and established the Haitian National Police. The HNP had thus only existed for a decade when MINUSTAH arrived in 2004. At that point, the police force was severely weakened by a deteriorating economy, growing political instability and violence. Many HNP officers also lacked formal training and policing skills.

The devastating earthquake on 12 January 2010 inflicted a severe blow to Haiti’s already fragile economy and infrastructure. It is estimated that 220,000 people died in the earthquake, and 1.5 million people were displaced. The MINUSTAH mandate was extended in order to help rebuild Haiti. In October 2017, a smaller follow-up peacekeeping mission, the United Nations Mission for Justice Support in Haiti, MINUJUSTH, took over. The new mission focused on further strengthening the rule of law institutions and the HNP. MINUJUSTH completed its mandate in October 2019, which marked the end of 15 years of consecutive peacekeeping in Haiti. Today, the United Nations Integrated Office in Haiti (BINUH) plays an advisory role to the Government of Haiti, focusing on political stability, good governance, and the rule of law. BINUH consists of around 20 strategic advisors on specific fields, including policing, gender and SGBV. BINUH does not work on an operational level and is only present in Port-au-Prince.

Sexual and gender-based violence in Haiti

The deployment of the Norwegian specialized police team (SPT) under MINUSTAH was a response to the spike in sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) in the aftermath of the 2010 earthquake. Sexual and gender-based violence is far from a new phenomenon in Haiti and was a serious problem also before the earthquake. Occupying forces, military and paramilitary groups have a history of sexually assaulting Haitian women and girls and of using rape as a political tool. In the shantytowns of Port-au-Prince, rape is commonly perpetrated by the armed gangs who control the area. Rape was previously considered an offense to an individual’s moral integrity or honor and was not made a criminal offense to an individual’s physical integrity until 2005. The earthquake exacerbated women’s existing vulnerabilities through mass displacement and social and economic dislocation. It also destroyed the few existing protection mechanisms against SGBV. Women and girls became targets of sexual violence and exploitation in the chaotic and unsafe internally displaced person (IDP) camps, where adequate security and access to services was lacking. One study estimates that as many as 10,000 individuals were sexually assaulted in the six weeks following the earthquake.

The HNP was never sufficiently equipped to combat SGBV, and the destruction of much police infrastructure in the earthquake further worsened the situation. Victims who reported sexual and gender-based crimes in Haiti reportedly often faced discriminatory and sexist attitudes among police staff. Widespread corruption, lack of competence regarding correct procedures for investigating and responding to SGBV and a shortage of police resources led to high dismissal rates of the few cases that were taken to court. Victims’ fear of reprisals, economic dependency on the perpetrator, shame, community stigmatization and a lack of trust in the police and justice system contributed to few cases being reported. Combined, there was a de facto impunity for sexual and gender-based violence in Haiti.

The Specialized Police Team on Sexual and Gender-based Violence

Norway was invited by the UN to deploy police officers to Haiti under MINUSTAH in late 2010, and left with the closure of MINUJUSTH in early 2019. The idea of a specialized police team was reportedly initiated by the then Norwegian Police Advisor to the UN in New York, following discussions in the UN on how to improve the approach to UN policing in UN peacekeeping missions. The traditional approach to UN policing in peacekeeping was through individual police officers (IPOs) and formed police units (FPUs). IPOs have been used for capacity-building of host-state police and law enforcement in UN peacekeeping missions. However, the difference in policing cultures and approaches to police training, as well as the frequent staff rotations, have posed challenges to IPOs’ capacity-building efforts. It was believed that having a specialized team with a concrete project and with similar policing cultures would ensure more focused and effective activities, and that the personnel with the relevant expertise would be recruited to the mission. MINUSTAH had a greater focus on crime prevention than most UN peacekeeping missions at the time. When the earthquake struck and reports of sexual and gender-based violence in IDP camps soared, it was suggested that Norway – which at that time had Haiti as one of its selected Partner Countries in Development – would send a specialized police team with a focus on crimes of SGBV. As part of the preparations, Norwegian senior officers travelled to Haiti on a fact-finding trip where they met with the MINUSTAH mission leadership and key HNP officials who confirmed that police capacity training with a focus on SGBV was needed – and welcome. Following this, the Norwegian Police Directorate, assisted by the Gender Adviser in the Police Division at UN Department of Peace Operations (DPKO, now DPO) in New York, developed a concept that ‘concentrated specifically on strengthening the HNP’s capacities to prevent, investigate and prosecute sexual and gender-based violence of deploying a specialized police team to work on SGBV under MINUSTAH’. The focus on SGBV was also based on objectives in the HNP development plan, which was written by the UN in collaboration with the HNP. The concept of a specialized police team on SGBV was then adopted and approved by the DPKO Police Division. At the time, there was little formal guidance on the role of SPTs in UN peacekeeping missions, and the novel concept was initially met with some skepticism in the UN. The Norwegian government offered to fund the SPT through the UN, but the funds had to be earmarked for the team’s work on SGBV. The funding would come from the Norwegian government’s Women’s Grant (Kvinnebevilgningen) which supported projects on women’s and children’s rights and security.

The SPT initially consisted of a team of five SGBV experts from the Norwegian police, who were deployed to Haiti for a year at a time. As French and Haitian Kreyol are the official languages in Haiti, the team started including UN police from Francophone countries. They eventually started a partnership with Canada as they had a similar policing culture to Norway. During the development and implementation of the project goals, the SPT consulted extensively with local police and justice actors, and thus benefited from local knowledge about actual needs on the ground and how to best address them. This collaboration was also intended to create local ownership that would help ensure sustainability once the SPT mandate was over. Building SPT objectives on the goals in the HNP Development Plan was in line with the fundamental principle for UN police in peacekeeping missions that all capacity development should be demand-driven and appropriate in relation to host State needs. The team attributes its success partly to the identification of competent, goal oriented and motivated counterparts in the local community who they collaborated closely with.

The team also benefitted immensely from having access to their own funding outside of the UN framework. In UN peacekeeping missions, civilian, military and police personnel providing technical assistance and advice tend to be the main resource for capacity-building. Financial support for programming beyond the deployment of personnel is very limited and has not traditionally focused on capacity building of host-state institutions. Limited project funding to support programming “…has been identified as a key factor that limits the impact on intended beneficiaries’ in peacekeeping missions.” Having guaranteed funding of more than 2 million USD for the two project periods (SGBV 1, 2010-2014, and SGBV 2, 2015-2019) was, according to the team, an invaluable contribution to the results. The team, however, reported challenges in getting hold of their own funds from the Finance, Acquisition and Procurement Section under MINUSTAH and MINUJUSTH, due to complicated rules and regulations on financial procedures. This led to some delays of payments and even cancelled activities. Being assigned to other tasks in the mission, like assistance during elections, a lack of resources in the HNP and shifts in HNP leadership meant that some activities took longer than planned.

SGBV 1 (2010-2014): Professionalization and strengthening of operational capacity in the HNP

The main goal of the first SGBV project was to professionalize the human resources in the Haitian National Polce (HNP), and to strengthen the HNP operational capacities. Professionalization of the police was pursued by organizing and facilitating courses on basic SGBV investigation for Haitian police officers. One purpose was to give the HNP a better understanding of SGBV-related cases, and to establish appropriate methods for interviewing victims and witnesses, collecting evidence, and other procedural approaches. Another goal was to change the attitude and the way of thinking around SGBV crimes among as many HNP personnel as possible, on all institutional levels and in all of Haiti’s ten regional departments. To that end, the project supported a ten-day instructor’s training (“train the trainers”) of 35 HNP officers. The idea behind the instructor’s course was to produce a base of knowledge within the HNP, a platform that would help sustain, maintain, and be adapted to changes in society and the judicial system. In turn, these HNP trainers were used as trainers for a total of 1072 officers from all of Haiti’s regional departments in five-days courses on basic SGBV investigation developed by the HNP instructors in close collaboration with the specialized police team (SPT). The SPT and the HNP also developed four-day seminars for 51 senior HNP officers. The SPT hoped that a focus on high-ranking officers would help influence the priority given to investigations of SGBV. Women – who make up 10% of HNP officers – were prioritized for training. The SPT considered the training of women as important due to their position as female role models and the need to include women’s voices and perspectives in the discussion during courses. Participants were chosen by the Gender Focal Points in the HNP. The Gender Focal Points themselves also participated. According to the SPT’s calculations, over 25% of HNP officers in each department participated in courses on SGBV during the first project period. The team did thorough evaluations of the training courses, including surveying participants.

The SGBV training program was integrated into the basic training at the Haitian National Police School. From 2014, all new police cadets received one week of SGBV training during their seven months of training at the school. This included discussions of ethics and awareness-raising on SGBV issues.

The second objective of the first SGBV project was strengthening HNP’s operational capacity through infrastructure development. This resulted in building/refurbishing and equipping a total of 13 dedicated SGBV offices inside or near the police commissariats in nine of Haiti’s ten departments. The purpose of these offices was to provide suitable equipment for SGBV investigation, and to serve as a quiet, less public environment for the reception and interviewing of SGBV victims. The SPT met with HNP directors in each department to identify the need and location of each office. One of these offices was inside the Justinien Hospital in Cap Haitian, constituting (possibly) Haiti’s first One Stop Center. The intention was that victims of sexual violence could file complaints with the police while receiving health care and legal assistance in the same building, with the hope that this would lower the threshold for seeking help. The SPT also helped build/refurbish and equip an office for the HNP National Coordinator of Gender and Women’s Affairs and a classroom at the HNP Police School reserved for SGBV training of cadets.

The SGBV project’s first phase ended in December 2015 after having been extended for two more years in 2013 due to delays in the financial and procurement processes. Based on the outputs of the first SGBV project, a follow-up project was developed. The surplus from the budget was transferred to the SGBV 2 Project.

SGBV 2 (2015–2019): Developing the Unit to Combat Sexual Violence (ULCS) and further specialization.

While the SGBV 1 project aimed to build a base for SGBV work within the Haitian National Police (HNP), SGBV 2 targeted the further development of those investigating SGBV cases at the specialist level. The project proposal for SGBV 2 built on the Haitian National Police Strategic Development Plan (2012-2016) which identified the need to develop a specialized unit on SGBV within the HNP Central Directorate of Judicial Police (DCJP). The Unité de Lutte Contre les Crimes Sexuels (ULCS) – the Unit to Combat Sexual Violence, was established in 2015 under the DCJP. Strengthening the unit became the main priority for the specialized police team (SPT) the coming years.

The purpose of the ULCS was to have a centralized SGBV office with national responsibility to develop common strategies and procedures that would guide the HNP’s response to SGBV. The unit would also oversee the application and harmonization of these strategies and procedures across the country, in particular with the SGBV offices in the regional departments. The ULCS would also take charge of professional development and develop focus areas and national campaigns on SGBV. The unit was intended to follow-up on the other SGBV initiatives implemented over the years, and thus secure sustainability after the departure of the SPT.

In 2018, the ULCS moved into a new 170 m2 building with a waiting room, offices for 13 investigators, interview rooms, meeting rooms, kitchen, and toilets, equipped with office furniture, computers, printers, internet access and other necessary office equipment. Ten additional investigators were added and received training on SGBV investigation during a five-days intensive course at the Quebec Police Academy. The training of the ULCS investigators involved interview techniques in SGBV cases, such as building trust, practicing active listening, understanding how memory works, non-verbal communication etc. An instructor from the Haitian National Police school in Port-au-Prince also participated in the Quebec training. The SPT originally intended to assist the ULCS in setting up a website on SGBV prevention with information about the ULCS services, prevention campaigns, and information on what kind of support the police and the legal system could offer to SGBV victims. However, due to limited access to computers – both in the HNP and among the general population – it was decided that a ULCS Facebook page, which was accessible through personal smartphones, was a better option.

The ULCS and the SPT participated in developing and implementing the new HNP Strategic Development Plan 2017-2021. Part of this involved improving statistics on SGBV, which are poor and unreliable in Haiti. Prior to 2018, there was no database on SGBV crimes in Haiti. To address this and keep track of cases, the SPT helped install a newly developed case registry program on ULCS computers, with the intention of having this rolled out in HNP police stations in all of Haiti’s regional departments as well. The SPT, together with instructors from the police school, also assisted the HNP in developing a Standard Operation Procedure (SOP) for police investigation of SGBV cases and disseminated electronic and hardcopy versions to police stations around the country, as well as to new cadets at the Haitian National Police School. Implementation of the SOPs in Haiti’s regional departments was combined with an assessment trip of the SGBV offices built under SGBV 1.

Further professionalization of the HNP continued under SGBV 2 through training of HNP officers. This included specialized courses on management and SGBV, child interviewing, and crime scene management, with a total of 249 participants – of which at least 180 were women. Whereas SGBV 1 had focused only on the Haitian National Police, SGBV 2 also focused on cooperation throughout the judicial chain. This included SGBV training courses for 116 judges from Appeals courts in all jurisdictions in 2017-2018. The aim was to strengthen judge’s knowledge and capacity concerning SGBV crimes and to improve coordination and collaboration between actors in the judicial chain. Formerly trained instructors were used with the intent to boost local ownership and sustainability. As part of SGBV awareness raising beyond the HNP, the SPT also held 12 two-days workshops to discuss SGBV from a local community perspective. The objective was to facilitate ‘sit togethers’ in all of Haiti’s regional departments, where key stakeholders and community leaders in local communities were invited to develop a common understanding of SGBV cases and victim care, including best practice on SGBV prevention, and to take new insights back to their communities. Participants included HNP officials, judges, local councilmembers (‘kaseks”), mayors, psychologists, doctors, vodou representatives, catholic and protestant priests, student associations, and journalists. A total of 221 people participated in the local community workshops, including 132 men and 89 women. The workshop was led by a female judge specialized in SGBV and representatives from the ULCS unit in Port-au-Prince.

The SPT also helped organize four international seminars at the Haitian Police School in Port-au-Prince, with the objective of introducing international standards on preventing and investigating SGBV crimes and inspire HNP and other justice actors on how to improve their practices. It was also a goal to bring different actors working on SGBV in the justice chain together to create a better understanding of the work that is done and to able these actors to connect. 583 people participated, and the seminars received publicity in Haiti and abroad.

The SGBV 2, as the previous project, achieved all its planned activities. The SGBV 2 benefited from the knowledge base and the contact network that was established during phase one. Clearly defined goals, frequent reporting and thorough evaluations after each activity provided a basis for learning, motivation, and sense of responsibility for members of the specialized police team. When the team left – and with them the dedicated funding – in February 2019, there were concerns that the SGBV efforts would disintegrate. Local counterparts expressed determination to continue with several of the activities, such as the International Seminar and the SGBV workshops with local community actors. The Chief of the Criminal Affairs Office (BAC) communicated that he intended to recruit 8 new investigators to the ULCS unit and place it higher up in the DCPJ organizational structure. Two Canadian UN police officers became responsible for follow-up and transitions towards BINUH, which was established in October 2019.

Relevance, effectiveness, and sustainability of the SPT activities

During the nine years they were present in Haiti, the Norwegian-led specialized police team (SPT) produced many outputs intended to build the capacity of the Haitian National Police (HNP) to prevent, investigate and prosecute sexual and gender-based violence. This section will look beyond the immediate results and assess to what extent they contributed to achieving the overall objectives. To that end, this section will look specifically on the relevance, effectiveness, and sustainability of the SPT’s initiatives, and comment briefly on impact where possible. Put short: Did the SPT’s initiatives work and will they last?

The SGBV offices in the HNP Commissariats

Between 2012 and 2014, the specialized police team supported the establishment of 13 offices dedicated to SGBV investigation in nine out of Haiti’s ten departments, including the one in the Justinien Hospital. In Haiti, many police stations lacked the necessary equipment for investigating SGBV and could not offer privacy for victims who wanted to report cases. Since there is a serious social stigma towards victims of SGBV in Haiti, creating a safe and suitable space for receiving SGBV victims was an important contribution to combatting SGBV. To identify the need and location of each office, the SPT consulted with HNP directors in each department. There were initial concerns by the team that, as soon as they left, the offices would be used for something else or fall into disrepair. The last official assessment of these premises by the SPT themselves was done in combination with the implementation of the Standard Operation Procedure (SOP) 2016 and 2017. For this report, updated information on the status of the SGBV offices was done through the help of BINUH and the Gender Focal Points in the HNP who interviewed staff at the SGBV offices and provided the author with updated photos in May 2021.

Today, 9 out of the original 13 SGBV offices are still operational. The office in Port Margot (Nord) was set on fire by a mob in April 2013 and never rebuilt. The Fond-des-Negres office (Nippes) closed and was moved to a new location in Miragoane (Nippes). The SGBV offices in Mirebalais (Centre) and Aquin (Sud) have also closed and report that SGBV cases and victims are taken care of by HNP staff at the commissariat or in neighboring SGBV offices. For some victims, this may entail a longer and more expensive journey to offices specialized in SGBV, which may raise barriers for filing complaints to the police. This may have decreased the effectiveness of these efforts in these specific departments.

The remaining offices are still used for SGBV investigation. A total of 46 HNP officers are assigned as SGBV Focal Points throughout these offices. All officers have reportedly received SGBV training, but there has been no new training since 2018. According to recent updates, these offices are functioning but with many logistical limitations and they are not sufficiently equipped. Most lack electricity and basic, necessary equipment, such as functioning toilets, computers, printers, cameras, office supplies and chairs. The Haitian National Police (HNP) reportedly does not provide investigators adequate equipment, and they continue to operate with equipment received during the implementation of SGBV projects under MINUSTAH and MINUJUSTH, of which much has broken down or has been stolen.

The case registry program introduced by the specialized police team is not being used in the SGBV offices, and no statistics on reported cases are available. This makes it difficult to measure effects based on reported cases. During the UN peacekeeping missions, SGBV cases were collected and registered by UN police travelling to the commissariats in the regional departments. It is not in the mandate of the new United Nations Integrated Office in Haiti (BINUH) to collect statistics in the departments and there are currently no reporting lines between the SGBV and Gender Advisor in BINUH and the SGBV offices. Hence, the follow-up of the SGBV offices in the districts has not been done in any systematic way since the SPT’s last assessment trip in 2016-2017. The SPT reported that at the time, they lacked the capacity to do a more qualitative and systematic assessment of the work being done at the SGBV offices. The deterioration of the offices is likely a consequence of lacking follow-up and limited resources allocated from the HNP.

When asked about whether NGOs working on SGBV issues were aware of the SGBV offices, and whether they used to bring victims to these offices, responses were mixed. One NGO reported that they had heard about the offices at the time of inauguration, but that more publicity was needed and that victims were not necessarily aware of what kind of services they could provide. Nor was there any known phone number where the SGBV staff could be reached directly. The NGO in question preferred to accompany victims to the justice of the peace (a judge at the lowest level of court) to file complaints in cases of flagrant offences. One NGO reported that staff were mostly unaware of the SGBV offices, but this seemed to vary across departments. A third NGO however did have the habit of orienting victims towards the specialized offices in the commissariats in the area where they worked. These findings suggest that there are differences in the offices’ visibility, accessibility and how they are used, which is likely influenced by local leadership and exacerbated by a lack of organized follow-up. It appears that more publicity around the SGBV offices and its services is needed. This can be achieved through a closer collaboration with NGOs and women’s groups providing victim support.

The assessment by NGOs working with SGBV of the quality of work in the police offices was generally positive, but with some challenges. One NGO reported that the offices both provided support and collaborated well with women’s organizations. Another NGO stated that the reception of victims was of very good quality. Victims were reportedly listened to in an attentive way. HNP officers provided sufficient assistance with filing complaints and referred victims to specialized organizations like health clinics when needed. One NGO claimed that victims were usually treated better at the SGBV offices than in ‘ordinary’ police stations around the country. However, often cases were never followed up, which, according to one NGO, caused victims to seek remedies elsewhere.

The One Stop Center at Justinien Hospital

The SPT supported the One Stop Center in the Justinien Hospital, Cap Haitian, North Department. The co-location of health services, police and legal assistance was a pioneering concept in Haiti. This initiative responded to the challenge of medical certificates in Haiti. Though not technically required by law, the medical certificate is treated as an essential piece of material evidence by the justice system in sexual violence cases. However, to get hold of a medical certificate, a victim must seek medical care within 72 hours of rape to preserve evidence. The ability to act quickly depends on the victim’s knowledge of health services and capacity to travel. Women who report a rape without having a medical certificate risk being accused of lying, and their cases are often dropped. Co-locating health services and the police under the same roof may lower barriers for women to seek help and increase chances that their cases prevail.

The study finds that the One Stop Center appears to have been effective but short-lived. BINUH reports that the center has closed down (see details below), but some evidence indicate that it may have had an effect on reported cases during the time it was operational. The number of reported SGBV cases registered in the North department of Haiti, home of the One Stop Center, increased from 56 cases in 2012 to 102 cases in 2015. This was the only one out of ten departments with a noticeable increase in reported cases. Statistics for the other departments have remained stable during the same period. This may also be linked to the fact that the proportion of HNP officers who received SGBV capacity training from the SPT was higher in the North department than the average in the rest of Haiti. Although statistics in Haiti is unreliable, the numbers suggests that the presence of the One Stop Center and the high level of SGBV-trained HNP may have lowered the threshold for victims of SGBV to file complaints.

However, according to the National Coordinator of Women’s Affairs in the HNP, the One Stop Center is no longer operational. Collaboration between the health services, legal services and the police was reportedly challenging from the very beginning. Internal disputes over management roles, particularly between the police division and the civilians, weakened the unit over time. There was also reportedly a lack of follow-up from the UNPOL Operational Pillar in the years after the creation of the center. The last official visit registered was from the US Embassy in November 2014. The lack of staff supervision, cooperation difficulties, a shortage of funding and the advanced state of disrepair has led to the closure of the unit. As of June 2021, the police office inside the hospital is reportedly still in use. However, no further details on the current status of the office, nor updated statistics on SGBV crimes, could be provided for this study.

The Unit to Combat Sexual Violence (ULCS)

The Unit to Combat Sexual Violence (ULCS) is still operational, and counterparts praise how the unit receives victims of SGBV. Still, the unit is not fully serving its intended role as responsible for following up and continuing the work under the SPT. Strengthening the ULCS was the main goal of the SGBV 2 project. One concern among SPT members was that the brand-new office space inside the Central Directorate of Judicial Police (DCPJ) premises would soon be taken over by something other than SGBV investigation. This has not happened yet. 13 HNP investigators are still working on sexual and gender-based violence in the unit. There have also been shifts in leadership at the ULCS unit, and the unit has had problems in the past with leaders being targeted with violence and quitting. The current leader has not received training under the SPT. The ULCS staff report that they have received no training on SGBV since 2019. In 2018, the Chief of Criminal Affairs Office (BAC) communicated intentions to recruit 8 additional investigators, but this has not yet happened. Nor has the unit been placed higher up in the DCPJ organizational structure as hoped.

The ULCS receives cases from the commissariats and welcome victims directly to their office. They also collaborate closely with organizations providing legal assistance and victim support. All NGOs consulted for this study were aware of the ULCS, and those present in the Port-au-Prince area collaborated very closely with the unit. Sources noted that the quality of services at the ULCS was generally good, and that the unit could sometimes play an advisory role to other justice actors working on SGBV, which suggests a high competency among staff on SGBV investigation practices. The personnel at ULCS were particularly praised for how they received and interviewed victims. As stated by one major NGO providing victim support: “Obviously, victims are treated better at ULCS than in normal police stations. The welcome is very cordial. The interview takes place in a discreet space. One very often feels empathy in the attitude of investigators towards survivors.” In other words, victims at ULCS do not seem to be met with the same discriminatory and blaming attitudes commonly found among Haitian police. This suggests that training of specialized SGBV investigators in the ULCS have had an effect in the sense that they create a more welcome environment for victims of SGBV which may inspire more victims to file complaints.

However, the case registry installed by the SPT is not really being used, which makes it hard to assess how many SGBV cases are registered with the ULCS and how many cases proceed to the prosecutor’s office. There is a lack of reporting between the ULCS and the SGBV offices in the departments, who do not provide statistics on sexual and gender-based crimes to the ULCS. This hampers efforts to measure effectiveness and future impact. Moreover, it affects the progression of cases. The effect of the case registry system becomes very limited as long as it is not being used systematically. As stated by one NGO:

… there is no follow-up being done. One gets the impression that the work of this office ends with the recording of the complaint. We must continually repeat testimonies to help investigators remember cases. In this regard, for over a year, we have not stopped pushing investigators on more than a dozen cases of rape against minors and young adults. To date, we have no information on what has been done. Such delays in processing cases greatly facilitate the escape of suspects and discourage survivors from continuing the legal process.

The effectiveness of ULCS unit is severely hampered by a lack of means. After the end of MINUJUSTH, the unit has no international funding, and it is now the HNP who are responsible for maintaining operations. Insight into the HNP budget was not available for this study, so it is unclear how much financial support the unit receives. However, according to some HNP sources, the ULCS unit has been somewhat neglected by the HNP leadership. This is reflected in the lack of material resources: The ULCS building has no internet and no fixed phone, and the unit lacks vehicles, fuel, and protective gear to summon people for questioning and to visit crime scenes. One NGO reported that the ULCS had been called upon in cases of emergency, but that they never managed to arrive on the scene due to logistical problems which led to cases being dropped.

The lack of means also hampers effective collaboration between the ULCS and the SGBV offices in the departments. One indented role of the ULCS was to sustain and follow-up on the SGBV initiatives after the departure of the specialized police team. This role is difficult to perform without sufficient means to communicate and travel. The increased insecurity and political instability in Haiti since the departure of the UN peacekeepers has further complicated travelling. ULCS staff claimed that the ULCS initially did some awareness raising and advising the population on what to do in cases of SGBV, but these initiatives have fallen through due to lacking means and logistical challenges.

Training and workshops on SGBV

According to sources in BINUH, the one-week course on sexual and gender-based violence in the 7-month basic training at the police school has been ongoing since 2013. The school has its own personnel responsible for training who received training at the police academy in Quebec, and the classroom is still devoted to SGBV training. Between 946 and 1348 new recruits received the training each year. This means that a total of 6976 new cadets have received basic training on sexual and gender-based violence at the school since 2013. However, there have been no new promotions since 2019 due to the sociopolitical crises that has been ongoing for the past three years. At the same time, sources in BINUH report that the police force is losing around 400 officers every year as officers retire or resign. According to BINUH, there are plans for a new class of cadets during 2021. However, this may be postponed yet again due to the upcoming constitutional referendum and parliamentary elections scheduled for later this year, which are expected to cause political turmoil, and the recent spike in infection rates of COVID-19.

One ambitious goal of the SGBV projects initiated by the SPT was to contribute to an attitudinal change in the HNP through training. It is hard to measure the effect of the various workshops, seminars, and courses on attitudes towards sexual and gender-based crimes without a comprehensive baseline study. It is also difficult to link potential attitudinal change directly to the SPT efforts rather than to other awareness raising initiatives by various actors. Though largely anecdotal, the SPT’s own assessment of training and sources interviewed for this study claimed to have detected some attitude change among participants in workshops and training. For instance, a Catholic priest uttered at the first day of the SGBV workshop in his department that it was not possible for a man to rape his wife as long as they were married. Two days later, after hours of discussion with members from his local community under the leadership of a Haitian female appellate judge and SGBV expert, he claimed to have changed his mind completely. And a vodou priestess claimed that she did not know what to do when women and girls from her community had been victims of rape until the workshop. After the workshop, she knew how to help and which other members of her community to contact. The choice of having workshops where discussions were led by Haitian counterparts who knew the Haitian justice system and local challenges connected to SGBV, seems to have been productive. During these workshops, the SPT mostly helped out logistically and financially, rather than “lecturing”. Including participants from the local community such as priests, youth leaders, vodou representatives and local councilmembers, in addition to HNP officials and other justice actors, shows that realities on the ground were taken into account when designing the workshops. More specifically, this relates to the role that informal justice plays in Haiti and the fact that few Haitians interact with formal justice actors during their life. Increased collaboration between actors in the local community on SGBV issues may be important to combat SGBV.

The findings from the ULCS unit and the SGBV offices suggest that staff who have undergone specialized training in SGBV treat victims better and are competent enough in their field to advice other justice actors working on SGBV cases. 97% of 884 HNP officials who responded to the team’s evaluation survey at the end of an SGBV training course reported that they were able to perform better or much better after the SGBV training. Although this type of self-assessment has several weaknesses, it suggests that the content of the courses responded to the capacity gaps and needs in the HNP. This is in line with other findings from Haiti which shows that training on SGBV actually works. According to a study from 2011, lawyers note that since the earthquake, with the increased awareness of gender-based violence, “…there has been some improvement among those police officers that have undergone training on how to deal with victims of GBV. The failure to adequately respond is a function of some police officers’ lack of such training, as well as confusion as to their roles and when or how to arrest individuals. There is a noticeable difference in the reactivity between officers who have been well-trained and those who have not been sensitized in cases of GBV in particular”.

With this in mind, it is likely that the extensive training of the HNP and the wider chain of justice – reaching 1744 participants during the two SGBV projects, in addition to 583 participants during international workshops and 6976 cadets at the Haitian National police school – may have contributed to at least some professionalization and attitudinal change with regards to sexual and gender-based violence. However, this study finds that SGBV training and awareness-raising initiatives have largely ceased: There have been no new promotions from the HNP Police School and no more SGBV workshops or International Seminars since 2019 due to a lack of funding and the ongoing political crises. The ULCS’ awareness-raising responsibilities have also waned. Knowledge needs to be maintained to have an impact, but the current financial and socio-political situation seriously hampers the effectiveness and sustainability of the SPT’s training efforts.

Conclusion and lessons learned

This report has followed up on the SGBV projects initiated by the Norwegian-led specialized police team (SPT) under the MINUSTAH and MINUJUSTH. By collecting data from Haiti two years after the departure of the SPT, the study assesses the development and status of the different SGBV initiatives with regards to relevance, effectiveness, and sustainability. During the two SGBV projects, the SPT team achieved a long list of outputs and activities in the form of training of the Haitian National Police (HNP) and other justice actors, constructing suitable office space for SGBV investigation and training, creating a specialized unit to combat SGBV, and more. This study has assessed to what degree these activities have contributed to a better, more professional, and harmonized approach to SGBV in the Haitian National Police.

To what extent did the SPT do the right thing? SGBV had de facto impunity in Haiti, which suggests that the focus on preventing, investigating and prosecuting SGBV was appropriate for the Haitian context. The focus on SGBV was adopted based on an observed and very pertinent need for assistance after the earthquake in 2010. The earthquake both destroyed police infrastructure and made particularly women and girls in Internally Displaced Person (IDP) camps extra vulnerable to sexual and gender-based violence. Engaging in fact-finding trips; building the project objectives on the Haitian National Police Development plan; and collaborating closely with the Haitian National Police, justice actors and other local counterparts both when developing and implementing activities; and adjusting activities according to evaluations and local realities when needed, appears to have helped the SPT’s projects address real needs on the ground and in the HNP. Furthermore, the focus on building police capacity was in line with MINUSTAH and MINJUSTH’s mandate to professionalize the HNP and strengthening rule of law institutions. The focus on SGBV was also in line with the Norwegian Government’s focus on women, peace and security in conflict-affected contexts.

To what extent did the SPT achieve its objectives? The effectiveness of the SPT in terms of desired outcomes is uneven. The project-based approach of a specialized police team with their own funding for programming helped achieve a wide range of outputs, which was acknowledged by the UN mission and eventually helped appease skepticism towards the novel concept. However, there is a difference between direct outputs and wider/long-term effects of interventions, and some of the SPT’s stated outcomes – like “professionalization of HNP staff” and “strengthened specialized SGBV capacity” are too vague to measure systematically. The lack of available statistics on reported and prosecuted SGBV crimes in the SGBV offices in the Commissariats and in the ULCS makes it hard to assess the effect of these outputs, as well as future impact. Still, the qualitative data from this study suggests that extensive training may have had some positive effects, exemplified by how the ULCS unit is praised for being knowledgeable and taking care of victims. However, a lack of means, follow up, and systematized registration of cases severely hampers the effects of the unit and the other SGBV offices around the country. It matters little that victims are well received if they do not seek out these services, if cases are dropped due to lacking resources, or if offices are forced to close.

To what extent will the benefits last? Sustainability was a major concern during the SGBV projects, and the specialized police team took care to improve sustainability through aligning its goals with the Haitian National Police Development Plan, “training-the-trainers”, implementing Standard Operational Procedures (SOPs), creating the ULCS unit to do follow-up, and implementing an SGBV training course into the curriculum at the Haitian National Police School, just to mention some. However, the sustainability of the SPT initiatives suffer from a halt in funding and a lack of economic progress in Haiti. With the end of MINUJUSTH, financial and logistical support for police reform programs is concluded, of which the HNP has become completely dependent. The HNP has struggled to provide basic policing services to the population since. In 2019, staff shortages and lack of resources in the HNP became frequent complaints, leading to police officers joining on the protests that had been sweeping the country for more than a year, staging a walk out from police stations nationwide. Prospects for sustainability are bleak in the current economy which is gradually deteriorating. Actors involved in police reform during peacebuilding in Haiti have previously been criticized for not doing enough to ensure that “the economic conditions in Haiti did not hinder progress or sustainability of reform.” For the first time in 13 years, the HNP received a significant budget increase in 2020 as a response to escalating gang-related criminality and the following public outcry. So far, this has had scant impact on police development and is largely reserved for fighting gang violence and providing security during the upcoming elections. Police reform continues with support from the UNDP and Canada, among others. BINUH leadership has expressed will to continue the work started by the SPT, but the mission does not have the capacity to follow up on all initiatives. Canada and BINUH are discussing sending Canadian police officers to Haiti to assist, but this is still very much up on the air and depends on how the political situation develops.

What can we learn from this study of the Norwegian-led SPT on SGBV in Haiti? First, having an earmarked budget for the SPT’s projects helps immensely on producing outputs. However, due to the project-based approach of SPTs – which is temporary in nature – it is important to consider how these outputs will be funded and sustained once the team is gone. Without secured funding, chances are the framework established by the SPT will deteriorate and expected outcomes will not be achieved.

Second, follow-up of activities is vital for their effectiveness and sustainability. The Norwegian-led SPT in Haiti reported that they lacked resources to follow up on past activities. Resources should be allocated to the SPT to follow up on completed activities to see if they work as intended, and to identify and address challenges to their effectiveness and sustainability. There is also a need for improved collaboration between SPTs in UN missions and other UN agencies on the ground, like UNDP. Remaining UN agencies could be responsible for follow-up purposes after the SPT and the UN mission leave. However, in order to fulfill this role, these agencies need external funding.

Third, better collaboration between SPTs and other UN agencies can contribute to a more holistic approach to police reform. It is important to focus on the wider chain of justice as the challenges connected to SGBV investigation, like lacking capacities and discriminatory attitudes, are also found higher up in the justice system. As this may be outside of the SPT mandate, collaboration with other UN agencies is needed. Similarly, including local community leaders in SGBV awareness-raising may help ground the issue.

Fourth, in line with other research on police reform in Haiti, this study finds that training can be effective in building police capacity. However, with the enormous outflow of officers from the HNP and no new recruits since 2019, one risks that this capacity decreases. It is thus important to ensure that the Haitian National Police School is up and running and able to deliver trained police officers.

Last, in order to assess effectiveness – and in the longer run, the wider impact – of SPT projects, it is important to clearly state expected outcomes in more measurable terms. Vague and unclear objectives make it hard to measure achievements beyond direct outputs. It is also important to continue monitoring activities after their completion in order to be able to say anything about real outcomes and the wider impact of the intervention.