Women in the Judiciary in Guatemala: Living between Professionalization and Political Capture

1.1. Women Judges: Perspectives on Institutional Change

1.2. Judicial change in fragile states

2. Women in the judiciary in Guatemala

2.1. Background: Changes and Continuities

2.2. An in-depth look at statistics

3. Career Paths and Appointments: Becoming a Female Judge

3.1. Career Paths and the School of Judicial Studies

3.2. A flawed appointment system

4. Training and Evaluation: Double-edged swords for women

4.2. Training in Legal Pluralism and the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

5. Security and Employment Conditions: Between a Lack of Protection and Discrimination

5.2. Working conditions: wages and retirement

6.1 Femicide and Other Forms of Violence Against Women Courts

6.2. Violence against women and the experience of women judges

7. The Political Capture of the Courts in Guatemala: Implications for Women Judges

7.1. Judges associations: a battlefield

7.2. “Regressions” and their effects on women judges

Conclusions and Recommendations

How to cite this publication:

Rachel Sieder, Ana Braconnier, Camila De León (2022). Women in the Judiciary in Guatemala: Living between Professionalization and Political Capture. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI Working Paper WP 2022:2)

Studies of female judges have tended to focus on the Global North, analyzing the factors that explain the presence or absence of women in the courts, the impact of informal institutional cultures on their professional opportunities, and whether they adjudicate cases differently from their male counterparts. Most of these studies assume that “glass ceilings” or patriarchal relationships are the main obstacles to women’s career advancement in the judiciary. “Glass ceilings” refer to invisible barriers created by unwritten rules that prevent women from advancing to decision-making positions in their professional careers. However, there is less analysis focused on the experiences of women judges in fragile states where, despite reforms to increase judicial independence, external pressures and informal politics within the judiciary continue to limit judges’ independence. What can the study of women judges in fragile or regressive authoritarian states tell us about the procedures and prospects for institutional transformation?

Our analysis of the situation of women judges in Guatemala reveals that they experience pressures to limit their independence in gender-specific ways. Focusing on women’s experiences as they enter a judicial career and work as judges enriches our understanding of the limits to judicial independence and the process of political capture in fragile states, as well as the ways in which gender differences manifest themselves in patriarchal social and institutional cultures.

About the authors

Rachel Sieder is Research Professor at the Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social (CIESAS). Ana Braconnier is a Postdoctoral Researcher at CIESAS, Mexico City. Camila De León is a lawyer and researcher in socio-legal issues based in Guatemala City.

About this publication

This report is part of the project “Women on the Bench: The Role of Female Judges in Fragile States,” coordinated by Elin Skaar (Chr. Michelsen Institute, Bergen), with Pilar Domingo (Overseas Development Institute, London) and Siri Gloppen (University of Bergen), 2017- 2022. The project is funded by the Research Council of Norway (RCN) through its NorGlobal program (CMI-17038/RCN-274500). See https://www.cmi.no/projects/2122-women-on-the-bench

Parts of this paper were presented in the Seminar on Empirical Studies of Law (SEED) of the Instituto de Investigaciones Jurídicos (IIJ) at the UNAM, Mexico, and in seminars for the Women on the Bench project. The authors are grateful for the comments and suggestions of Karina Ansolabehere, Erika Bárcena, Erin Beck, Mayra Ixchel Benítez, Juan Bertomeu, Elvyn Díaz, Juliana Franco Calvo, Pilar Domingo, Siri Gloppen, Pedro Ixchiu, Aslak Orre, Francisca Pou, Andrea Pozas Loyo, Luis Ramírez, Julio Ríos Figueroa, Ruth Rubio Marín, Camilo Saavedra, María Paula Saffón and Elin Skaar. The analysis presented in this paper is the sole responsibility of the authors.

1. Introduction

Studies of female judges have tended to focus on the Global North, analyzing the factors that explain the presence or absence of women in the courts, the impact of informal institutional cultures on their professional opportunities, and whether they adjudicate cases differently from their male counterparts. Most of these studies assume that “glass ceilings” or patriarchal relationships are the main obstacles to women’s career advancement in the judiciary. “Glass ceilings” refer to invisible barriers created by unwritten rules that prevent women from advancing to decision-making positions in their professional careers. However, there is less analysis focused on the experiences of women judges in fragile states where, despite reforms to increase judicial independence, external pressures and informal politics within the judiciary continue to limit judges’ independence. What can the study of women judges in fragile or regressive authoritarian states tell us about the procedures and prospects for institutional transformation?

Our analysis of the situation of women judges in Guatemala reveals that they experience pressures to limit their independence in gender-specific ways. Focusing on women’s experiences as they enter a judicial career and work as judges enriches our understanding of the limits to judicial independence and the process of political capture in fragile states, as well as the ways in which gender differences manifest themselves in patriarchal social and institutional cultures.

With the support of numerous international development cooperation agencies, the professionalization of the judiciary in Guatemala was promoted after the end of the armed conflict in 1996. Subsequently, specialized courts were created to address key human rights issues such as corruption, serious human rights violations during the internal armed conflict, and femicide. Both the establishment of a professionalized judicial career structure and the creation of these courts opened opportunities for women judges. Compared to other countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, Guatemala has a relatively high percentage of women judges (43% in 2018). However, the increasing capture of state institutions by alliances between corrupt ruling and business elites and organized crime underscores the judiciary’s growing lack of “societal autonomy” (Bowen 2017). As we suggest in this working paper, ultimately political capture has trumped judicial professionalization and modernization. While the political capture of the judiciary by criminal structures does not necessarily prevent the participation of women judges per se, it does deter human rights and anti-corruption-oriented female judges from pursuing their careers.

This study presents a qualitative analysis based on a sample of 25 female judges (see Annex 1). To obtain a representative sample from the universe of cases, selection was random but included women judges at all levels, from Justice of the Peace courts up to the Supreme Court of Justice. We interviewed judges in Guatemala City and in municipalities of the departments of Quetzaltenango, Sololá, and Chimaltenango. Although not an exhaustive sample in terms of quantitative validity, it allows us to observe similarities and variations. In 2019, we conducted semi-structured interviews and recreated life histories of the female judges in the sample. We complemented the interview material with a review of judicial archives (through access to public information from the Judicial Career Council), Guate Compras (to trace patterns of contracting in public institutions), and articles from the main newspapers.

We develop our analysis focusing on four elements that, according to our interviewees, help guarantee judicial independence: (1) professionalization; (2) security conditions; (3) working conditions; and (4) institutional design. First, professionalization (through training and postgraduate studies) increases judges’ skills of legal argumentation and therefore strengthens their criteria to issue more robust judgements. Without professionalization, we would expect to find greater ambivalence in the legal criteria brought to bear in adjudication. Second, optimal security conditions afford protection from internal and external pressures and threats, allowing rulings to be handed down with greater autonomy. Without such conditions, judges are arguably less protected, and therefore more inclined to yield to pressures and threats. Third, with better working conditions, including decent salaries, adequate retirement pensions, safe facilities, and reasonable workloads, judges are less exposed to economic and political pressures, threats, or simply physical and mental exhaustion that hinders their optimal professional performance. Fourth, the greater the transparency in the institutional architecture (including opportunities that open or close with the establishment of specialized courts, nomination procedures, and the actions of professional associations and judges’ associations), the greater the clarity in the rules for a professionalized judicial career. Otherwise, networks of influence and informal relationships may come to privilege certain judges over others. We found that each of these four elements relevant for judicial independence had specific gendered dimensions.

The working paper is divided into seven chapters. In this Introduction, we review the literature that considers the relationship between a greater presence of women judges and changes to the judiciary. In contrast to most of the research on women judges which focuses on stable democracies, our approach seeks to understand the challenges of institutional transformation in cases of fragile states with compromised judicial independence.

In the second chapter, we contextualize the situation of women judges in Guatemala from the 1980s through to the present. Despite the differences between a judicial system under dictatorship and a more democratized system, we find enduring continuities that point to the limits of judicial change in transitions to democracy.

In the third chapter, we describe prevailing career paths and the appointment system in the judiciary as described by our interviewees. Although career paths are varied, entry-level appointments are strongly influenced by gender-based power relationships.

In the fourth chapter, we focus on judges’ professionalization. Judicial reforms since democratization have contributed to the specialized training and education of female judges. However, the system of performance evaluation suffers from certain flaws, which in turn have a negative effect on female judges.

In the fifth chapter, we describe security and employment conditions, addressing structural aspects of the judiciary and the insecurity stemming from matters that female judges hear in their courts, and the location and physical conditions of the courts themselves. We also briefly addressed issues of salaries, retirement, and workloads. These affect both male and female judges, but gender inequalities tend to make it even more difficult for women to perform optimally as professionals.

The sixth chapter analyzes the experiences of women judges in the courts dealing with Femicide and Other Forms of Violence against Women. These institutional spaces have been key to advancing gender perspectives within the judiciary and opening possibilities for greater gender justice for Guatemalan women. However, we suggest that absent a commitment on the part of the Supreme Court of Justice to promote gender training throughout the judiciary, and under conditions of political capture, gains made to date may suffer reversals.

In the seventh and final chapter, we analyze the current political situation in the judiciary with special emphasis on the implications for women judges. We conclude that, in contexts of political capture of the judiciary in fragile states such as Guatemala, “glass ceilings” could be replaced by “impunity ceilings”. These impunity ceilings generally prevent women judges committed to human rights from progressing in their judicial careers, in contrast to women judges who favor the status quo.

1.1. Women Judges: Perspectives on Institutional Change

An extensive literature has focused on women in different branches of government, although there is less research on women’s presence and experience in the judiciary compared to the legislature (Basabe-Serrano 2017, 2019, 2020; Jarpa Dawuni 2021; Schultz and Shaw 2013). Most research focuses on the Global North and politically stable judicial systems, which are nonetheless characterized by exclusionary, elitist, and patriarchal policies and institutional cultures (Mackay, Kenny, and Chappell 2010). These studies have contributed to our understanding of the impact of formal rules and informal norms and networks on women judges’ experiences and decision-making, while enhancing our understanding of their role in transforming the judiciary. The study of women judges is thus part of a broader field of research on institutions, focusing specifically on the importance of gender parity in institutional change (or lack thereof), a perspective that has been termed “feminist institutionalism” (Mackay, Kenny, and Chappell 2010). Such studies have tended to emphasize the impact of women judges on judicial politics in terms of “democratic legitimacy, increased public confidence, and trust in the judiciary.” (Feenan 2008, 491).

Four main approaches have been developed to analyze why gender matters in judicial politics, focusing on experiences in the Global North, particularly in Anglo-Saxon societies: (1) the “differential” approach; (2) the “equal opportunity” approach; (3) the “diversity” approach; and (4) the “feminist” approach.

The differential approach asserts that simply being a woman judge contributes to “enhancing women’s legal status” (Feenan 2008), but also claims that “women bring an ethic of care to justice issues in contrast to men’s perspectives” (Feenan 2008). This perspective has been criticized for standardizing female judges and assuming a stereotypical female ethic of “sensitivity and empathy” (Hunter 2013, 210), while ignoring the intersectionality of complex identities and interests that different female judges may embody.

In contrast, the “equal opportunity” approach stresses the need for “equal opportunities” for women through judicial appointments based on meritocracy, i.e., their qualifications (Feenan 2008). Such an approach argues that equal opportunity will break traditional male dominance within the judiciary, challenging the patriarchal view that only male judges have the legal knowledge necessary to dispense justice. It also argues that the inclusion of qualified women in the courts is critical to building judicial legitimacy.

The “diversity” approach argues that greater representation of diversity within the courts is fundamental to democracy, as the judiciary must reflect the pluralism of society in terms of class, gender, ethnicity, and race (Ifill 2000; Feenan 2008; Rackley 2013). Developed mainly in the United Kingdom, the United States, and Canada, this perspective promotes women’s entry to the judiciary and law schools to transform these more elitist and traditionally male-dominated spaces.

Finally, the fourth “feminist” approach asserts that feminist judges are more likely to include women’s subjectivities and even intersectional analyses in their judicial decisions (Hunter 2008; 2013). These critical socio-legal studies argue that the supposed “universalism” of the law really reflects male subjectivities. To have feminist judgments, however, the presence of women judges alone is insufficient; there need to be laws to combat gender discrimination and violence, and feminist judges exercising gender perspectives within the courts.

These four analytical approaches have improved our understanding of how women affect the judiciary and the different viewpoints that may be expressed through their decisions. After significant efforts to achieve more equitable gender representation in judicial institutions, we would expect greater opportunities for women in the courts to advance their careers and for more judicial change to occur. As Dressel, Sánchez-Urribari, and Stroh (2018) note, however, assumptions about judicial behavior and legal-institutional change derived from the Global North do not always fully correspond to the realities of courts in other contexts.

1.2. Judicial change in fragile states

To date, comparatively less attention has been paid to women judges in fragile states where armed conflicts and political settlements have shaped both judicial institutions and the possibilities for judicial independence. Constitutional and institutional reform to strengthen the rule of law has been a central focus of peacebuilding and transitions to democracies (Domingo and Sieder 2001; Gloppen, Gargarella, and Skaar 2005; Brinks and Blass 2018). In such contexts, the importance of intergovernmental organizations and international development and cooperation agencies in peace processes has meant that certain institutional prescriptions for promoting the rule of law became universalized in the 1990s and 2000s (Domingo and Sieder 2001).

Judicial independence is linked to the ways in which judges are appointed or elected, the stability of their positions, their career prospects, personal security, and the guarantees that they can exercise their roles without undue interference from other branches of government, their superiors, or other social actors. External judicial independence refers to selection and appointment procedures that protect judges from undue interference from other branches of government. Reforms in the Global South supported by international institutions have focused specifically on promoting greater external judicial independence by reforming selection and appointment procedures and establishing merit-based judicial career systems.

Yet, as Bowen observes in her study on the limits of judicial autonomy in Central America, threats to judicial independence emanate not only from politicians maneuvering for more compliant courts, but also from a wide range of powerful social actors (Bowen 2017). Bowen explores the relationship between external judicial independence and what she calls “societal autonomy”: safeguards against pressure from social actors, particularly corrupt businessmen, perpetrators of gross human rights violations, and organized crime groups. Judiciaries characterized by low societal autonomy may no longer be formally controlled by the executive, but “hidden powers” exercise “more diffuse and clandestine control” through corruption and different forms of coercion, ultimately undermining formal rules intended to guarantee judicial independence (Bowen 2017, 175-6).

In fragile states, “relational dynamics between judges and other judges, politicians, political groups, legal actors, and other individuals and collective entities matter” (Dressel, Sanchez-Urribari and Stroh 2018: 574), often a great deal and in markedly different ways than how they matter in the Global North. In this regard, the internal workings of the judiciary and the degree of internal judicial independence are particularly important.

Internal judicial independence implies de jure and de facto guarantees that judges’ decisions will not be influenced or determined by their superiors through mechanisms such as administrative sanctions, arbitrary transfers, or obstructing promotions. Low internal judicial independence facilitates co-optation, where judges at higher levels exert undue influence over the lower ranks of the judiciary. If high-level judges can exert this type of pressure on their subordinates to secure specific outcomes, then internal independence is compromised. Internationally supported reforms in fragile states to strengthen internal judicial independence include internal evaluation systems, incentives for judges, and accountability procedures. However, to date there is little empirical research on how these systems work in practice, and specifically for women judges.

Theories of judicial politics, which focus on the relational and informal political networks that shape the context in which judges operate, can better explain the dynamics and outcomes of the judiciary in contexts of low societal autonomy. Judges function as part of their own courts, but also as part of networks within the judicial apparatus that may at the same time have links to broader political and social networks (Dressel, Sanchez-Urribari, and Stroh 2018; Bowen 2017). A focus on the experiences of women judges in fragile states allows us to analyze the dynamics that exist between gendered social norms, formal institutional arrangements, and informal politics within the judiciary. Institutional prescriptions for greater judicial independence have tended to ignore the weight of informal mechanisms, including underlying gender inequalities and political dynamics that constrain or promote women judges.

In this working paper we explore the gendered dynamics of judicial politics in Guatemala, where reforms in the 1990s promoted formal judicial independence through professionalization, opening significant opportunities for women judges, but where ultimately low societal autonomy is decisive for their experiences of entering and practicing as judges.

2. Women in the judiciary in Guatemala

Studies of women judges in Guatemala and Latin America have pointed to both the achievements and limitations that they have experienced in the judiciary over time and under different political regimes. Many of these achievements and limitations persist, although the experience of women judges today also signals significant changes. In this section, we first review some background on women judges in Guatemala prior to the justice reforms implemented in the 1990s, and secondly, present an overview of the gender balance in the judiciary up to 2019.

2.1. Background: Changes and Continuities

A few years after the political transitions towards democratization in Central America, the Costa Rican author Tirza Rivera Bustamante in her book “Las juezas en Centroamérica y Panamá” [Women Judges in Central America and Panama] pointed to the prevalence of “glass ceilings” for women pursuing a judicial career in the midst of a male-dominated environment, as well as the practice of corruption and clientelism within the judiciaries of the region (1991). She also noted the increasing “feminization of the legal profession” that contributed to greater participation of women in the practice of law across the region, including within national judiciaries. In addition, judicial reforms promoted by international institutions led to greater gender equity by seeking to democratize the legal profession. (Rivera Bustamante 1991: 65). However, this valuable publication, unique for its study of women judges in the region, was published before the reforms to the Guatemalan justice system that were spelled out in the 1996 Peace Accords.

In her description of the situation of women in the judiciary in Guatemala in the 1980s, Judge Olga Esperanza Choc reveals a panorama that diverges in some respects from the current situation outlined in this paper but is also surprising for its many similarities.

Three aspects are different: the percentage of women judges in the judiciary; the existence of an association of women judges; and the participation of women judges in high-impact positions. Judge Choc wrote in 1991: “Gradually, women have been incorporated into the judiciary, holding different positions; from janitor, clerk, secretary, judge, to magistrate” (1991: 184). According to her data for 1989, one of the nine sitting magistrates at the Supreme Court of Justice was a woman, while 7% of the appellate courts, and 11% of judges of first instance were women (Choc 1991, 184–85). Current figures show a greater participation of women in the judiciary (see Table 1). In almost thirty years, the number of women judges has increased fourfold. This increase is due to several factors, as we will see in the next section.

Table 1: Evolution in the percentages of women judges and magistrates

|

% |

1989 |

2018 |

|

Supreme Court of Justice |

11 |

50 |

|

Appellate Courts |

7 |

38 |

|

First Instance Courts |

11 |

44 |

Sources: Prepared by the authors, comparing 1989 data presented by Olga Esperanza Choc (1991) with our data collected in 2018 from the Court Management System.

Second, in addition to this increase in female judges, we find a greater number in high-impact positions, and no longer just in family, children’s, or criminal courts (because they are less lucrative, as Rivera Bustamante explains (1991: 69)). For example, in 1991 in Guatemala, just one of the eight magistrates of the Supreme Court of Justice was a woman; by 2019, when the data for this paper was collected, the Supreme Court of Justice had gender parity. The same can be said of the more recently created jurisdictional bodies, such as the High-Risk or Femicide courts (see chapter six), which are mostly occupied by women judges.

Third, Choc wrote in 1991 that “in Guatemala there has never been, nor is there, an organized grouping of women judges. There is a great deal of individualism and professional competition is very high” (1991: 187). This is no longer the case since the Association of Women Judges of Guatemala was created in 2018. As we detail in chapter seven, this association aims to improve the working conditions of female judges and magistrates.

In contrast, five aspects of similarity or continuity stand out: the profiles of women judges; the underrepresentation of Indigenous, Xinca, or Garifuna amongst women judges; the motivations for becoming judges; patriarchal beliefs; and the practice of corruption and clientelism.

First, the profile of female judges remains very similar to the one described by Choc. “The average age of female judges is 35 years old, most of them are single (I am referring to women who have never married, are divorced, or are single mothers). As for men, the average age is 40 and 95% are married” (1991: 186). Currently, according to the female judges we interviewed, the majority are single mothers. This data is relevant for the analysis of working conditions, insofar as female judges encounter various difficulties in balancing their judicial careers with family life (discussed in more detail in the next section). Judge Choc identified a gap in the 1990s: “Indigenous women and men do not have any level of participation and decision-making in the policies and actions of the current ‘national state’” (1991: 183). This underrepresentation of Indigenous women amongst judges continues to date. It was not possible to obtain an overview of the judiciary in terms of ethnicity and race since no statistics are collected on these criteria within the institution. There is only a breakdown by gender, as we will show below.

Second, the women who pursue a career as judges maintain the same motivations: “the desire to impart justice, to improve their working conditions and their economic and social status, to be able to attend conferences and training courses, even to be selected for scholarships granted by international organizations,” recalls Judge Choc (1991: 186). These motivations, as we show in this paper, are still valid.

Third, for Judge Choc there is a glass ceiling in the Guatemalan judiciary preventing women from occupying decision-making positions due to “cultural, economic, ideological and political beliefs”.... (1991: 187). To date, the prototypical role of women is centered on care of the home and family. There is a generalized idea that women in the judiciary will work in different positions, but focused on “fields traditionally classified as suitable for the female sex (family, minors) or in administrative support positions” (1991: 185). While women’s entry into the judiciary is now determined by their professional training in accordance with current regulations, their promotion to appellate courts and the Supreme Court is still determined by other elements, particularly the “political reasons” identified by Judge Choc over two decades ago. (1991: 184). Today, the “political reasons” refer to the capture of the justice system by criminal networks through the nomination and performance evaluation systems (as discussed in the last chapter of this paper on the “impunity ceiling”).

Since the 1990s, then, observers have noted that in the region “in practice the judiciaries lack independence. Some observers have called them “the Cinderella of the central government... Corruption, political interference and lack of financial independence and trained personnel, have characterized the region’s judicial branches [...]” (Rivera Bustamante 1991: 72–73). To address this lack of judicial independence and democratize Guatemala’s justice system, reforms to the judiciary were carried out after the Peace Accords by means of the Commission for the Strengthening of Justice and its report “Una nueva justicia para la paz” [A New Justice for Peace] (1998). The measures included a Judicial Career Law and the creation of the School of Judicial Studies and the Judicial Career Council. However, as Bowen observes, the introduction of novel forms of institutional design “provided multiple entry points for corruption and allowed social actors to use the law selectively in a kind of perverse formalism” (2017: 144), undermining judicial independence. The creation in 2007 of the International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG in Spanish), a United Nations entity whose central objective was to coordinate and strengthen the national penal system institutions, was another chapter in the long process of attempts to strengthen judicial independence and fight impunity (Bowen 2022). In 2017, the Judicial Career Law was revised (by decree 32-2016) during discussions about reforms to the justice sector led by civil society sectors, the Public Prosecutor’s Office, CICIG, and the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) in Guatemala. This reform sought to change the system for electing members of the Judicial Career Council, ensuring a greater degree of separation of administrative and jurisdictional functions within the Supreme Court of Justice. The professional training offered at the School of Judicial Studies sought to give greater weight to academic training and merit as a means of advancing in a judicial career. One of its objectives was to guarantee judicial independence, given that judges should be chosen for their academic and professional profiles, hopefully excluding the corruption that may result from the positioning of individuals beholden to certain interest groups.

In sum, challenges to guaranteeing judicial independence persist and, as we discuss in the last chapter of this paper, have been heightened by the political capture of the state by criminal structures, and the increasing criminalization of independent judges and prosecutors.

2.2. An in-depth look at statistics

With the negotiations to end the internal armed conflict and the signing of the Peace Accords in 1996, international donors and Guatemalan professionals supported judicial modernization and professionalization. Key commitments were approved to improve accountability and respect for human rights. As a result, the number of courts increased, as did specialization within the judiciary. The current structure of the judiciary is shown in Organizational Chart 1:

Organizational Chart 1: Structure of the Judicial Branch

Source: Judicial Organism

At the top is the Supreme Court of Justice. The Supreme Court is made up of thirteen magistrates, including the presidency, which is rotated annually and elected by the thirteen magistrates. The Supreme Court is organized into three chambers: the criminal, civil, and amparo [writ of protection] and pre-trial chambers (the latter is responsible for granting writs of protection and evaluating whether state actors should maintain immunity from prosecution). Below the Supreme Court are the appellate courts. Numbering thirty in all, they are divided into criminal, civil, family, labor, children and adolescents, administrative, and fiscal law. This number includes the departmental mixed chambers of appeal that hear all branches of law in the country’s departments [sub-national territorial divisions].

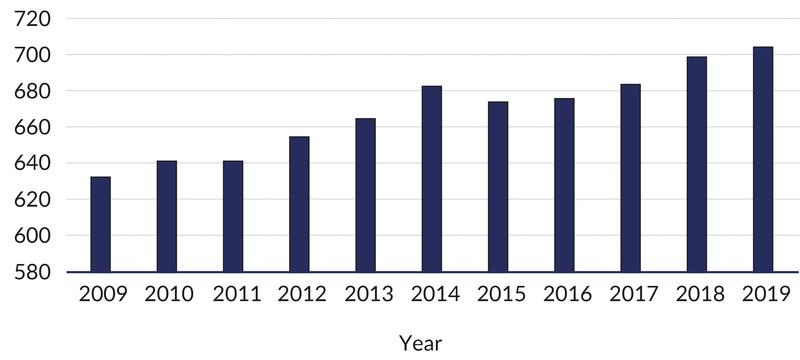

As a result of the modernization and professionalization process, the number of courts increased, in part driven by the creation of specialized courts to address violence against women (created in 2012), drug trafficking, and high-level corruption (the High-Risk Courts). Table 2 depicts the creation of courts and tribunals in the country from 2009 to 2019.

Table 2: Number of tribunals and courts from 2009 to 2019.

Source: CIDEJ, Court Decisions published in the Official Gazette.

The creation of the professionalized judicial career through competitive exams to enter the School of Judicial Studies opened new opportunities for women to train as judges (see chapter three of this report). Professionalization boosted the presence of women in the judiciary such that, currently, about 43% of judges in Guatemala are women (Impunity Watch 2017: 14, and authors’ data from the Court Management System collected in 2019).

Judges at the lower levels of the judiciary, i.e., justice of the peace courts, courts of first instance, and sentencing courts, now enter exclusively through the professionalized judicial career path established by the School of Judicial Studies. The courts of first instance and sentencing courts include ordinary criminal courts and new specialized criminal courts created in recent years: Femicide and Other Forms of Violence against Women, and High-Risk (the latter focused on drug trafficking, transitional justice cases related to serious human rights violations, and complex corruption cases). The judges of these specialized courts are recruited directly through competitive calls for first instance judges and justices of the peace, who entered the judiciary through professional competitions. The other first instance courts hear civil, family, labor, child and adolescent, administrative and tax cases, with a total of 218 of these courts throughout the country. At the bottom of the judicial hierarchy are the 370 justice of the peace courts, one in every municipality, that deal with civil and criminal cases.

Appointments to the appellate courts and the Supreme Court of Justice, according to Article 215 of the Political Constitution of 1985 (amended in 1993), are made every five years by the national Congress from lists of candidates proposed by nomination commissions, one for the appellate courts and another for the Supreme Court. This selection system entails two stages. In the first, the commissions consist of the rector of one of the country’s universities (who presides), the deans of the law schools at each of these universities, representatives elected by the College of Lawyers and Notaries of Guatemala (CANG), and representatives elected by the magistrates of either the appellate courts or the Supreme Court of Justice, depending on the court in question. In the second stage, the plenary of the Congress elects the magistrates based on the lists sent by the Nominating Commission. Until 2022, eligible candidates included judges who had advanced in their judicial careers and lawyers who are not professional judges, although in practice lawyers have been increasingly favored over career judges.

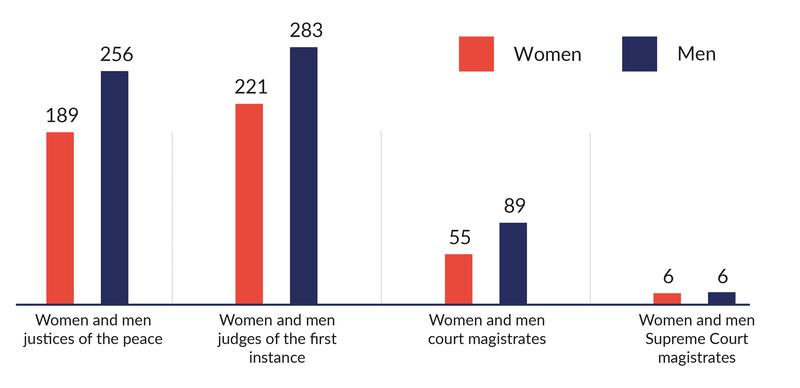

Basabé-Serrano (2017) suggests that, although the prevailing patriarchal political culture means that courts are not spaces that women can always easily access, or where they can advance their careers, they are not necessarily excluded from the highest levels of the judiciary. In Guatemala, women have been appointed to become magistrates of the highest courts. During the first two decades of the 21st century, three female justices presided over the Supreme Court (Ofelia de León, 2005-2006; Thelma Aldana, 2011-2012; and Silvia Patricia Valdés, 2016-2017). In 2019, the Supreme Court had gender parity for the first time, with six male and six female justices. In addition, the last three heads of the Public Prosecutor’s Office were women and two female candidates competed for the presidency of the country in the 2019 elections. Although there is no legislation in Guatemala that promotes gender quotas in positions of power, the courts and tribunals have undoubtedly been a space for women’s participation in public office, as identified in table 4.

Table 4: Percentages of women and men in the judiciary and Magistracy (in 2018).

|

|

Women |

Men |

Total |

|

Total Judges |

410 |

539 |

949 |

|

First Instance |

221 |

283 |

504 |

|

Justice of the Peace |

189 |

256 |

444 |

|

Total Magistrates |

61 |

95 |

156 |

|

Supreme Court |

6 |

6 |

12 |

|

Appellate Courts |

55 |

89 |

144 |

|

Total |

471 |

634 |

1105 |

|

Percentage |

42.6 |

57.4 |

100 |

Source: Prepared by the authors based on data from the Court Management System.

Viewed another way:

Table 5: Bar depiction of staffing of women and men in the judiciary and Magistracy (in 2018).

Source: Prepared by the authors based on data from the Court Management System.

Women have undoubtedly made significant advances within the judiciary over the past three decades. However, as we posit in the next section of this paper, the prevailing patriarchal political culture means that the courts are not spaces women can always easily access, or where they can advance their careers beyond particular “glass ceilings” and “broken rungs.” The growing trend toward state capture by criminal structures, particularly at the highest levels of the judiciary, has reduced opportunities for independent, human-rights-oriented judges, many of them women, to ascend to the high courts. Even so, a good number of women choose to enter the judiciary, advance in their judicial careers, and pursue specialized training. According to data collected from our sample of interviewees, their experiences are very varied. Despite this variety, there are common gender-related difficulties, since inequalities for women continue to exist.

3. Career Paths and Appointments: Becoming a Female Judge

The experiences of female judges indicate that the judiciary has been an institution providing opportunities for professional women. Their backgrounds prior to entering the judiciary varied, and sometimes they brought specialized prior knowledge in specific subjects. In addition, the School of Judicial Studies has strengthened their academic training. However, the appointment system continues to be marred by discrimination based on gender, by sexism and sexual harassment.

3.1. Career Paths and the School of Judicial Studies

Although our sample is not representative of the entire universe of women judges, our findings suggest that most female judges graduated as lawyers or notaries from the Universidad San Carlos de Guatemala, at its Guatemala City and Quetzaltenango campuses. Many entered the School of Judicial Studies directly after graduation to undertake training as judges. Others indicated that they followed different career paths prior to becoming judges. In several cases, they were teachers, or worked in national and international non-governmental organizations as project managers, in foreign institutions, in government positions, or as lawyers.

The interviewees saw the judiciary as an institution that provides job stability and opportunities for career advancement. Despite being trained and qualified to work in the judiciary, some female judges indicated that they chose to put their training and professional careers on hold to take care of their children and families.

“You ask how I entered the judiciary. I stopped working because I had my second child, and my work situation became more difficult to reconcile with my personal life. In other words, how do you juggle both aspects? I decided to resign because my children were a higher priority. My income changed substantially. It damaged me as a person, limited me as a professional. That’s what made me think about having to separate [from my husband] because it wasn’t the life that I thought it would be.”

Professional experience prior to entering the judiciary can contribute to developing interpretations focused on specific issues. For example, according to a female judge of the first instance in a Criminal Sentencing Court for Crimes of Femicide and Other Forms of Violence against Women:

[In her previous job], “there was a third program, which was for youth animators, who were also colleagues who trained young people in how to prevent unwanted pregnancies, and these young people had to reproduce this knowledge, on the basketball courts, in the high schools. For me it was a very good experience because it gave me a more scientific knowledge of sexuality and a gender perspective. In other words, I was already working on the issue of equality in the exercise of sexuality. And it also helped me to reject the myths of gender roles, the myths of virginity [...].”

These prior work experiences complement the courses and training within the judiciary. One of aims of the reforms made to the Judicial Career Law was to increase professionalization through continuing education within the School of Judicial Studies. The idea was that initial and core university studies be complemented with postgraduate courses and specializations.

The reformed School of Judicial Studies has made it easier for women professionals to begin a career in the judiciary. With the signing of the Peace Accords in 1996, specifically the Agreements on Strengthening Civilian Power and the Role of the Army in a Democratic Society, the need for a law regulating the judicial career was made explicit. In 1999 Congress approved the Judicial Career Law (Decree # 41-99 and Agreement 6-2000). This mandate was crucial for the democratization of the justice system since it sought to promote a transparent system for the election and promotion of judges and magistrates. With this law, the School of Judicial Studies of the judicial branch (formally created in 1986) was reformed and is currently the institution in charge of “planning, executing, and facilitating the technical and professional training and education of judges, magistrates, officials, and employees of the judicial branch, in order to ensure excellence and ongoing professional training for the efficient performance of their positions” (Judicial Career Law, 1999).

There are two main types of admission to the judiciary for candidates aspiring to judgeships:

- by election, through the School of Judicial Studies, where candidates from outside or within the judiciary study for two years at the school and compete for a position; and

- by appointment.

Prior to the approval of the Judicial Career Law in 1999, it was common for judicial clerks to be promoted to the position of judge through a series of internal exams. Several of the female judges interviewed who studied at the School of Judicial Studies previously worked as clerks, and in some cases underscored that they were encouraged to apply for the career by the judges with whom they worked. Typically, they started from the lowest positions on the ladder, but over the years the field opened so that they could eventually aspire to become judges.

“...the 20 years that I worked as a clerk .... most of us were women and I had female judges as bosses, so that motivates you to continue your career, to say, well, I also want to be a judge, that’s what motivates you; they were excellent judges.”

Since 1999, candidates for judgeships apply to external calls (to which trial lawyers can apply) and/or internal calls (for candidates who are already within the judiciary). They can then enter to become judges through career-path professionalization at the School of Judicial Studies. Several of the interviewees commented that the selection of candidates to enter the school was equitable in terms of gender. The first director of the School of Judicial Studies was María Eugenia Morales, a renowned feminist and jurist, who later became a Supreme Court justice. Her commitment to a selection policy that respected gender equity was undoubtedly instrumental in expanding the presence of women within the judicial career.

3.2. A flawed appointment system

The second option is to become a judge by appointment. According to Guatemala’s Constitution, lawyers who have practiced for at least five years prior to their appointment may be named as judges and magistrates. After completing courses at the School of Judicial Studies, the final grades of each class are published in ascending order. Pursuant to the judiciary civil service law and the career law, the Supreme Court must appoint the best qualified group as justices of the peace or judges of first instance (depending on the terms of the original call). Likewise, after having completed their professional studies, selected candidates must accept their appointment and go where they are assigned. A female judge from the first graduating class of the Judicial School in 1998 noted:

“They signed contracts to participate in all the training. They received a stipend and committed to accepting the judgeships they were assigned. So, given that commitment, they can’t say I want to be sent to such-and-such a place or choose the posting they want.”

It is particularly difficult for women with small children when they are assigned to a municipality far away from the cities of Guatemala or Quetzaltenango, where most professionals in the country live, study, and work. This is because in the justice of the peace courts judges are required to be available every day of the year, which supposedly means living in the municipality. However, in practice many tend to return to see their families on weekends, but this is only feasible if they work within commuting distance of their homes. One female judge commented:

“My first assignment as interim judge was in Canillá, a municipality in Quiché, which apparently is close [to where I lived], but it actually very far away. That was my first posting, and I took it up when I was about 4 months pregnant. And I left my daughter in Guatemala; she was about a year and three months old, my oldest daughter. So, I went when I was pregnant. The roads were impassable, terrible conditions. I couldn’t leave; the justice of the peace works 24 hours a day, 365 days a year without the right to rest. Far from home.”

This judge was not the only interviewee who pointed out that postings fail to take female judges’ family situations into account. Often, female judges enter the judiciary with young children and elderly parents. In these situations, postings often disrupt family ties, duplicating the judges’ work and family burdens. The current system of allocating judgeships makes it particularly difficult for women to pursue a judicial career, in effect constituting a facet of the “glass ceiling”.

The lack of an appointments system appropriate to women’s family situations is compounded by clientelism. Even if women have performed well in the School of Judicial Studies appointment as a judge has not been automatic. While discretional selectivity negatively affects both men and women, appointments combine both gender discrimination and factors of affiliation or loyalties, i.e., forms of clientelism. In the school’s first graduating class, female candidates generally received high marks, some earning the highest grades. However, these achievements did not always guarantee that they would be appointed promptly or easily. Appointments have sometimes been quite slow. Several female judges told us that, rather than gender being the main factor behind discrimination, political factors were involved, or “connections... for one to be appointed.”

Another judge commented that, in her graduating class, although three women qualified in first, second, and fifth place, none of the three was appointed:

“When we sat down to analyze, we saw that out of the top five places the three of us who had not been appointed were women, and we saw that there were people who had even failed courses who were men and who [nonetheless] were appointed [as judges].”

This judge, who ranked first in her class, sued the Supreme Court of Justice through an injunction filed at the Constitutional Court, which she won a year later. The Constitutional Court gave the Supreme Court five days to issue her appointment as a judge. In response, the Court assigned her to one of the most remote and least supported courts in the country. She served there for three years before being transferred to another region. She interpreted her transfers as a kind of reprisal by the judiciary, specifically because of interests linked to organized crime.

Another female judge who had scored very high in the first graduating class of the School of Judicial Studies (1998) commented that the results were never published because most applicants did not qualify. However, several men who had not passed the tests were appointed as judges. When she complained to a magistrate about this discrimination, he told her “You’re too young.” This female judge petitioned the judiciary, “I filed a complaint saying that there was corruption by criteria of friendship; I made him see that I was going to make it public.”

Finally, other types of gender discrimination, specifically the expectation of sexual favors in some cases, also exist within the appointment system. A female Supreme Court magistrate, who has fought against sexual harassment in the judiciary, said that rumors circulated that in order to begin a career or to decide where to assign judges, the president of the Judicial Career Council received favors or asked female judges to have intimate relations in exchange. In this regard, a woman judge said:

“They sent me to Zacapa, to the mountainous area. They appointed another male judge [to a less remote posting] and they sent me further away....... maybe because I didn’t arrive in a skirt…. later when they gave me my posting, I saw that the previous one had been revoked to give that position to a male colleague. There’s a lot of sexism [in the mountainous region]; to reach the villages you must travel in a police patrol car and it’s very hard for people to respect a woman’s authority because they prefer to see an older man [as a judge].”

The same Supreme Court magistrate confided that filing a case of sexual harassment within the judiciary continues to be a challenge. The difficulty lies in building a judicial authority for an internal-affairs jurisdiction able to judge powerful people, such as a president of the Judicial Career Council. At the time of the interview, the creation of mechanisms to tackle sexual harassment was still under discussion.

Even with professional qualifications, the lack of “connections” in judicial appointments exposes women to sexual harassment. According to one female judge:

“To be appointed you must...know people. In my case, I didn’t have any acquaintances.... I talked to a friend who was a woman justice of the peace and she told me ‘Look, the magistrate who works in this area can help you; he’s very accessible’. I went to the magistrate, it used to be by area, by region, but he didn’t have any vacancies available for me to be assigned as a justice of the peace. Then he told me ‘This other magistrate, he does have vacancies available to assign you. I started to ask around about what he was like, and they told me ‘Look, if you show up in a skirt, he’ll treat you well and will put you wherever you want’ so... It was a little sad for me to see that situation... obviously I said I’m not going to go in a skirt; if he wants to appoint me, I’ll go in pants and if not, it’s not for me. That was an unpleasant moment.”

Gender discrimination also occurs in the higher echelons of the judiciary. For example, a female Supreme Court justice shared the following:

“The Council [of the Judicial Career] put out a call for judges for the High-Risk courts. Two people applied, a man and a woman. The man had been working here for 15 years, but had two or three disciplinary sanctions; he’d been suspended from work and had been sanctioned three times in those 15 years for misdemeanors. She worked seven years without a single administrative offense. She had a higher qualification than he did and scored better in an evaluation. Who do you think the Council appointed? The man. He was the one who had administrative faults and sanctions and was poorly evaluated, but because he was the most senior of the two, the Council appointed him. Then we said that we wouldn’t endorse that appointment because according to meritocracy it was her turn. The Council didn’t change the decision; it left the [male] judge in post.... It’s difficult; you can see how opportunities are closed to women.

Several female judges told us that in certain regions of the country (rural areas, but in general throughout the eastern region), it was difficult for users of the judicial system to accept a woman as a judge, and more so if she was relatively young:

“My first posting was as justice of the peace in San Francisco El Alto and when I arrived, people would come in [to the courthouse] and say to me ‘Excuse me, is the judge here?’ I am the judge, come in, I would say to them.‘Ah no’, they would say, ‘we want to talk to a man’. No, I told them, I am the judge and it’s the same thing. ‘No, it’s not the same’, they would say, and then they would leave... There was another man who arrived... It made me laugh because he would say ‘What are you doing here? What are you doing sitting there? You should be at home.’”

This distrust of female judges is particularly acute in cases of domestic violence or disputes:

“There are times when they even insult you, ‘Yeah, of course a woman won’t rule in favor of men’, something like that almost always happens. Or they say, ‘Since she’s a woman, she’s protecting other women, so we’re discriminated against; that’s unconstitutional.’ I’ve heard that more than once.”

To conclude, for women entering the judiciary involves a decision to build a judicial career, guarantee one’s job security, and continue training with the support of the School of Judicial Studies. The system of appointments is flawed by gender discrimination and sexual harassment as well as by forms of clientelism, informal relationships, and social and political connections. The current appointment system negatively affects the performance of female judges by not considering their family situations (they are often the heads of household), and by influence peddling and clientelistic relationships that generally favor men, who, as our interviews reveal, are assigned to the most coveted jurisdictions. The weight of clientelistic relationships in assignments can lead to sexual harassment against women.

For female judges, the difficulties are not limited to the appointment system. The opportunities provided by professional training and points-based evaluation are also limited both procedurally (the rules for training and evaluation) and by everyday practices. Training and evaluation are thus double-edged swords for female judges.

4. Training and Evaluation: Double-edged swords for women

Through their initial training, continuing education and specialization, such as diploma courses, master’s degrees, or doctorates, female judges have found ways to develop specializations. Academic and professional training encompasses multiple topics and approaches. Training programs have also played a positive role in improving women’s performance evaluations for their career advancement. Ongoing professionalization, however, has also negatively affected female judges’ careers. While it has opened doors for them, because of its weight in evaluations, professional training has turned into a race to accumulate titles and diplomas.

The School of Judicial Studies has developed training and education programs and signed academic training agreements with universities and NGOs in Guatemala. Other training programs have been promoted by organizations, such as the Association of Judges and Magistrates, the Association of Women Judges, and the Association of Lawyers and Notaries of Guatemala.

In addition, in 2012 the judiciary created two more regional branches of the School of Judicial Studies, one in Quetzaltenango and the other in Chiquimula. This geographic decentralization benefited female judges by bringing training opportunities closer to them. A female judge who attended the school acknowledged:

“I went [to the School of Judicial Studies], yes, I remember, six months [training for] justice of the peace. The school was only in Guatemala City, but now it’s better because it’s in Xela [Quetzaltenango]. Then I always worked a few days and then [travelled to go to] the School.”

Postgraduate programs in agreement with national universities provide another training option. According to data obtained through public information requests, from 2015 to 2019, five agreements were signed to develop different academic programs. For some interviewees, these programs have been very helpful in advancing their training, professionalization, and specialization. For example, since 2017 an “Academic Updating Program” has been carried out with the Rural University of Guatemala. This plan offers an opportunity to graduate to judges who have completed master’s level classes, but who never completed their degree. As explained in the academic cooperation agreement, the Rural University offers a specific curriculum so that employees of the judiciary can graduate and obtain a university degree. In this way, judges and other justice practitioners can continue with postgraduate studies. A female judge noted:

“About two years ago, the judicial branch began encouraging judges who hadn’t finished their studies, or who had undertaken maybe one semester of a master’s program. The magistrates motivate us and make inter-institutional agreements between the judicial branch and the Mariano Gálvez University or the San Carlos [University]. They say, ‘look, if you haven’t finished a master’s degree, take advantage of this opportunity and work on it’. Or if you haven’t studied a master’s degree, ‘look, we encourage you to get a master’s degree.’”

Agreements have been signed with San Pablo University (2019) and Mariano Gálvez University (2016) for specializations in labor law. The former coordinates master’s and doctoral programs in labor law. The latter has offered postgraduate programs in labor law, social security, and business administration. Finally, the master’s degree in Gender and Justice, in agreement with Mariano Gálvez University, has existed since 2015 and was widely mentioned by our interviewees.

Thus, the School of Judicial Studies has generally expanded the possibilities for male and female judges to specialize. We are particularly interested here in training in gender and legal pluralism. Training in gender has opened opportunities for female judges to practice within the special criminal jurisdiction of Femicide and Other Forms of Violence Against Women (although, as discussed in chapter six of this report, there are also threats to their safety in these courts). In addition, training in legal pluralism and the rights of Indigenous Peoples also favors female judges, providing them with aspects to improve their deliberation in the communities where they work, while improving their scores in the points-based performance evaluations.

4.1. Gender training

Specializations in gender issues and access to justice were developed following the creation and expansion of laws aimed to address violence against women. The trainings are currently defined within the Institutional Policy of the Judiciary on Gender Equality and Promotion of Women’s Human Rights (Women’s Commission, 2016).

Funding from international cooperation agencies has been crucial to these efforts. The Women’s Commission of the Supreme Court of Justice has conducted workshops for the promotion of women’s human rights. Similarly, the Secretariat of Indigenous Peoples of the Supreme Court of Justice has provided training on access to justice for Indigenous women, developing intercultural approaches and exchanging experiences in conflict resolution combining the state’s justice system and Indigenous community justice. The Women’s Secretariat of the Executive Branch has also provided training on these same topics. International organizations (USAID, OXFAM, UN Women, OHCHR, Impunity Watch, among others) have also provided training covering intersections such as youth and gender, peacebuilding, security and justice, sexual violence, and post-conflict humanitarian planning.

In addition, according to reports released by the Supreme Court of Justice, the judiciary has signed agreements to promote these issues with the Asociación Movimiento por la Equidad de Guatemala (Association of the Movement for Equity in Guatemala, AME), the Instituto de Estudios Comparados en Ciencias Penales de Guatemala (Institute of Comparative Studies in Criminal Sciences of Guatemala, ICCPG), Mujeres Transformando al Mundo (Women Transforming the World, MTM), and the Myrna Mack Foundation. For example, together with the School of Judicial Studies, the Myrna Mack Foundation has run an academic program for judges and judicial personnel to facilitate access to specialized justice for women victims of violence. Programs have also been carried out in the different regions of the country to decentralize training.

Gender specialization was established by judicial policy. The master’s degree in Gender and Justice includes jurisprudential analysis at the national and international levels, differences in the study of rulings with and without a gender perspective, and analysis of public policies from a gender perspective. In this way, female judges are prepared to deal with these specialized cases and draw on sophisticated legal argumentation.

Several interviewees indicated that this has been especially helpful for women judges who sit on the criminal courts for Femicide and Other Forms of Violence Against Women. One judge stated:

“it’s been a very good experience because we have got to know each other… The project began with three of the specialized courts: Quetzaltenango, Guatemala, and Chiquimula. We were mostly women, although of course being a woman doesn’t mean you’re automatically committed to [a gender perspective]. However, those of us who started knew what the project was, that we had to apply the law and a gender perspective. Not all of us [were acquainted with gender perspectives] because the subject had not really been taught, only this training at the university. As a result, several schools were opened with master’s degrees in gender [...] We all went through that process of preparation and induction prior to starting here in the Femicide courts.”

As an incentive for specialization, scholarships have been offered. The same judge quoted previously commented that the master’s degree has influenced legal interpretation and the way justice is dispensed:

“As for the master’s degree in gender, I saw it in the newspaper, and it caught my attention. I said ‘women’s rights’, that’s great. I even invited several of my colleagues at the time. I was in the last year of my doctorate in criminological sciences. They said, ‘you’re crazy, that’s a horrible subject, what’s wrong with you?’ Well, I went and participated in the selection process because the scholarship was also granted through competition. [...] I loved it.”

During this interview, this judge emphasized her exceptional interest in academic training to achieve excellence. Her curriculum lists four master’s degrees, a doctorate in criminological sciences, and another ongoing doctorate in public administration.

4.2. Training in Legal Pluralism and the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

With the creation of the judiciary’s Secretariat for Indigenous Peoples (formerly the Indigenous Affairs Unit), abundant training in Indigenous Peoples’ law, Indigenous law, and legal pluralism has been developed.

“We have had trainings, workshops, and courses in Indigenous rights. In that sense the judiciary does care... there are many alliances with numerous international organizations that join forces, and we are in constant training about Indigenous rights.”

Learning a Mayan language is also encouraged, and knowledge of a Mayan language is considered within the points-based evaluation system. One female judge interviewed expressed an interest in learning a Mayan language to “break that language barrier”:

“The Secretariat of Indigenous Peoples offered a course, but unfortunately, it’s in the mornings…. I can be a very qualified judge, but if people don’t have access to justice [...] it won’t do me any good to speak the language if I’m delaying my cases, right? That’s why I didn’t start the course this time, but one of my challenges is to speak the language if I stay in Chimaltenango. Another challenge is to form a referral network in Chimaltenango where I can work in coordination with Indigenous authorities, where they can get acquainted with the state justice system, and we can get to know each other and work together, be on the same page; we both share the goal of justice. We started to find out who the authorities are, where they are located, we’re undertaking that process right now.”

Just as the School of Judicial Studies encourages the education and training of justice practitioners, the performance evaluation system also recognizes the amount of training received through a points system. According to the information we gathered, the evaluation system considers postgraduate university studies and training. As some female judges pointed out during our interviews, the Judicial Career Council has not yet drafted regulations to indicate the precise items to be evaluated and their weight.

According to information obtained through public information requests, the percentage distribution in the evaluations is difficult to understand. “Extracurricular merits” are measured in the performance evaluation (such as publications, university teaching, participation in the School of Judicial Studies, among other activities). Although these measures are intended to strengthen academic and professional training, female judges say they are impossible to achieve due to the work and family burdens explained above.

Judges are evaluated every five years by the judiciary. They need to demonstrate that they have undergone various kinds of training. As in most professional evaluations, no consideration is given to women’s family circumstances. For several of the female judges interviewed, this situation was far from ideal:

“You know what, another issue I would like to address is the issue of training. The appointments are for five years and every five years you must be evaluated and then analyzed, and there I feel a disadvantage because we are measured by the same yardstick as a male judge [...] They ask us for the same amount of training, the same knowledge, so that you score the same when you apply for positions. When you apply for positions, they don’t say ‘oh, because you are a woman, you have children’, they don’t say that. They repeat what your curriculum says. And if you are a mother, what time do you have for further education? Either you stop being one thing or you stop being the other. So, when they measure us like that, maybe it’s not the method, but the instrument they use to measure us; it automatically leaves you out because they are measuring us in the same manner.”

Another female judge commented:

“I believe that the gender issue has an impact because of your personal situation. For example, I’m sure that I got as far as I have because I don’t have a husband. Because I invest my time in my own training and no one is questioning me. For example, my children’s father: If I went to training and I wore a dress like this, he would ask, ‘Are you going to model or to study?’ So, what is he telling me? You know what the traffic is like in [Guatemala City]. So, you can’t say, ‘I’m going to be home at seven o’clock’ because that’s just not going to happen. So [then the suspicion is] ‘did she go to study or why did she take so long?’ All that weighs on you. I do see that many of my female colleagues stay home to avoid the risk of being late. Maybe they have other aspirations, but they put them aside to avoid problems.”

Some interviewees emphasized that women’s responsibilities prevented them from furthering their education. In any case, some aspect of life ends up being sacrificed to fulfill other responsibilities. The grades for university studies, training received, and extracurricular merits are evaluated equally for men and women. However, interviewees often pointed out that access to education and professionalization through training lacks equal conditions due to family and marital social norms reinforced by dominant gender ideologies.

Gender has an influence on access to training. However, the female judges we interviewed also pointed to other elements that restrict their access to education and training. For example, geographical factors make it difficult to access courses and other issues related to one’s position in the judiciary, as do high costs and limited enrollment openings on courses. In addition, a perverse effect of evaluation by points-scoring is that the search for education and training has become a race to accumulate points to move up the ladder. According to the interviewees, these difficulties transcend gender.

In the initial years, the School of Judicial Studies was located only in Guatemala City. According to a woman judge from Quetzaltenango who heard cases in Sololá, access to the School was differentiated not because of gender discrimination but because of geography:

“I don’t think there’s a gender bias. I really don’t see it. I feel that the opportunity cost is more to do with whether we’re based in the capital or other regions of the country, regardless of whether we are women or men. Obviously not all of us women can leave our home to go to the capital to train, so our opportunity cost is higher than that of women in the capital. For example, we used to leave [Quetzaltenango] at three in the morning to be at the School at 7:30 am, sometimes we couldn’t even have breakfast. We studied from 8 to 5 in the afternoon, then we had to face all the traffic in [Guatemala City], we would get home at midnight, and then go to work [the next day]. It is not the same as being in the capital, having breakfast, going to school, getting out in the afternoon, and arriving home. In other words, the opportunity cost is totally different.”

The same judge went further:

“They assign a score to your academic training inside and outside the judicial branch. For that reason, many from the capital have better curricula than those from the regional departments because they have access to training, and we don’t.”

The geographic location of the court therefore influences access (or lack thereof) to training. The Judicial Career Council must approve a judge’s request to enroll in training or postgraduate courses. Several interviewees say that these approvals are often difficult to obtain, especially because their court must not be left unattended:

“[...] we have to send a request to the Council and, on many occasions, they tell us that permission is denied and we can’t attend. I’ll be honest with you, sometimes I try in my free time, for example, four or five in the afternoon to attend a diploma course, but I’m on the alert because if I’m called by the court, I must go back. They demand academic credits and restrict our permissions, so it’s really complicated. Most of the time, most judges, well, we escape for a little while to be able to attend courses and fulfill the hours of training they require of us.”

According to our interviewees, as a justice of the peace, it is difficult to enroll in postgraduate courses or training because these courts must be permanently staffed. For example, one interviewee emphasized:

“In terms of training, the judiciary does not facilitate conditions, regardless of whether you’re a man or a woman, especially if you’re a justice of the peace. When you’re a justice of the peace, as originally [stipulated] you must remain in your court, it must be continuously staffed, then it’s quite difficult to study. In [a court of first or second] instance, it becomes a little easier.”

In addition, court officers don’t have access to many the trainings offered by the School of Judicial Studies. As another female judge pointed out:

“Court officers are not required to have [gender training]. In other words, someone applies for a position, and if they meet the technical requirements, they are given the post, but looking at the handling of daily work, they don’t seem to have a gender focus... they don’t seem to have taken ownership of that methodology.”

Another difficulty mentioned in the interviews is the limited number of enrollments available for courses. One woman judge acknowledged the efforts of the judiciary, stressing that:

“[Enrollment notices go out] throughout the region. That’s why when you go to enroll, there aren’t any places left. How many are there if we’re talking about the whole region, Retalhuleu, Huehuetenango, San Marcos, Quetzaltenango? They all come here. They can open a lot of places for you to receive training, but there isn’t enough space. But courses are being held, the effort is being made. The [Supreme Court] has worked hard.”

Tuition fees for graduate programs are high in relation to a judge’s salary. A female judge in the doctoral program observed:

“I am pursuing a doctorate in Labor Law at the Mariano Gálvez University. There’s an agreement with the judiciary regarding courses. I thought about one at San Carlos University, but due to family and time issues, I didn’t apply. I’m happy with the doctorate, but it’s hard, exhausting, there are exams every week. [...] It’s expensive to continue studying; you pay Q.2,000 per month for the doctorate, Q. 1,300 for registration, Q.3,000 for the thesis, Q.15,000 for the graduation ceremony.”

That same judge emphasized an aspect that came up numerous times in interviews. The search for training is closely linked to the performance evaluation requirements. Obtaining points has been an incentive for judges to pursue postgraduate studies or training. Thus, she said, “All this also is calculated in points: Two points for a master’s degree, three for a doctorate, out of a total of 100 established by the Regulations of the Judicial Career.”

As explained above, the performance evaluation takes into consideration academic, professional, and extracurricular merits through a points system. Several female judges emphasized that training is an area in which they can increase their score to hasten their promotion in their judicial careers. However, participating in postgraduate courses or training seems to have turned into a race to accumulate titles and diplomas. She explained:

“[the evaluators] come and say: ‘Show me records of this,’ they interview us, they tell us ‘Well, your academic record is worth so many credits or points. How many courses did you attend during the year? How many diplomas do you have? Do you have a master’s degree? So many points; if you don’t have a master’s degree that lowers your points […] Last year I was getting a doctorate, which is three years, but they told me ‘It doesn’t matter if you prove [that you’re studying], we’ll approve it [for points] when you graduate.’ Something else they ask you, ‘Diplomas, doctorates, are you a teacher?’ Yes, I’m a university professor, I tell them, because I also teach at night either at the Mariano Gálvez University or at the Rafael Landívar University here in Guatemala; I prove that I give classes because that gives you points; they regularly include it. Often, our workload as judges means there’s no time left for training, so you must study at the weekends. And what do you do about your family? Being a judge is a bit complicated, but ultimately you can manage everything.”

In summary, even though the School of Judicial Studies is a gateway for women that encourages the academic training and professionalization of female judges and other justice practitioners, experiences of entry into the judiciary continue to be characterized by asymmetrical relations between men and women. These asymmetries are not limited to gender discrimination alone, since our interviews reveal that women continue to face difficulties in obtaining jobs, even if they are the most-qualified students at the School of Judicial Studies.

5. Security and Employment Conditions: Between a Lack of Protection and Discrimination

Widespread insecurity in Guatemala means that women judges face specific challenges in their professional practice because of their gender. The experiences of women judges reveal the challenges they face in ensuring their safety; these are related to the different matters they hear in their courts, along with the location and physical conditions of the latter. Regarding job security, while issues of salaries, retirement, and workloads affect both male and female judges, social gender inequalities tend to add to women’s greater responsibilities and burdens of care.

5.1. Safety Conditions

Practicing as a judge in Guatemala can involve great security risks that have specific implications for women. Generally, there is no security detail assigned to justices of the peace, who depend on the National Civil Police or local civil authorities should problems arise. Security is reserved for courts of instance and specialized courts, although there is not always adequate coverage. Security officers are generally assigned when there are threats or attacks, which are common.