Missing from the picture: Men imprisoned for ‘moral crimes’ in Afghanistan

The law: men and consensual sexual crimes in Afghan criminal codes

The numbers: Men in prison for moral crimes

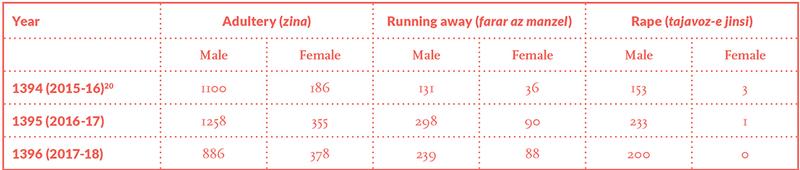

Table 1: Men and women imprisoned for adultery, running away and rape

How to cite this publication:

Aziz Hakimi, Torunn Wimpelmann (2018). Missing from the picture: Men imprisoned for ‘moral crimes’ in Afghanistan. Bergen: Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI Insight 2018:2)

Recent years have seen sustained focus on the prosecution of Afghan women and girls for ‘moral crimes’ such as adultery and ‘running away’. However, many Afghan men are also charged with and convicted for moral crimes. This paper examines how Afghan law penalizes men for consensual heterosexual acts, and presents statistics suggesting that hundreds of men are currently imprisoned for such ‘moral crimes’ in the country. It argues that although women are particularly vulnerable to prosecution for moral crimes in Afghanistan, debates and advocacy over this issue must include men’s experiences too.

Introduction

This paper provides a first discussion of a neglected topic in debates and activism about gender equality in Afghanistan – the prosecution of men for ‘moral crimes’, or more specifically, consensual heterosexual crimes such as adultery and elopement. Research and advocacy have almost exclusively focused on women and girls’ imprisonment for moral crimes. We argue that although women and girls are particularly vulnerable to charges of moral crimes, this does not justify a total omission of men’s experiences and situations. Men are not exempted from the controls imposed on sexuality in Afghan society and by the Afghan state, even if such controls are applied somewhat differently to men than to women. This paper summarizes how Afghan criminal law penalizes male consensual heterosexual acts, and presents some initial statistics suggesting that hundreds of men are currently incarcerated for such crimes. It ends with some pointers regarding the need for further research on the topic.

Background

The imprisonment of women for consensual sexual crimes such as adultery, attempted adultery and ‘running away from home,’ has received a fair amount of attention and scrutiny in post-2001 Afghanistan. At any one time during this period, between 300 and 600 women have been incarcerated in Afghan prisons for these ‘moral crimes’ (Human Rights Watch 2013; Human Rights Watch 2016). Activists and human rights workers – both local and international – have kept track of the number of women in jail for moral crimes, provided legal aid, and engaged systematically with the Afghan authorities on the issue. In particular, they have criticized the imprisonment of women for ‘running away from home’, pointing out that, in contrast to actual adultery (zina), running away from home (farar az manzel, lit. ‘escaping from the house’)2 is not listed as a crime in Afghan law.

(...) there is a noticeably lack of attention to the fate of men in debates and advocacy over moral crimes. Whilst there have been several reports on the number of women in jail for ‘moral’ crimes, we know of no attempts to map the number of men charged with, or imprisoned, for the same crimes.

Afghan legal officials have responded to this criticism by invoking article 130 of the Afghan Constitution, which they see as permitting the application of Islamic fiqh3 in matters not covered by codified legislation. In 2010, the Supreme Court issued an advisory directive4 sanctioning the charging of women who run away from home by defining it as ‘attempted adultery’ (eqdam ba jorm-e zina). This directive spelled out why, according to Sharia, women running away from home were committing a punishable crime. It argued that ‘runaway’ women who went to the home of ‘strangers’ (lovers, friends, neighbors) rather than straight to the appropriate authorities (police or judiciary) or to the house of relatives or legal intimates (mahram- e shara’i) were in danger of committing actions prohibited by Sharia, such as adultery or prostitution. By relying on the principle of the means of prevention in fiqh (sa’d-e- zaraye), the judges of the Supreme Court constructed a new legal category of ‘attempted zina’ on the basis of which runaway women are being prosecuted in state courts.

Subsequent government statements suggest there is some disagreement within the justice sector over whether women going to the house of ‘strangers’ can be charged with a crime. In 2012, the Attorney General’s Office issued a directive stating that ‘running away’ has not been criminalized under Afghan law and state prosecutors should not file criminal cases under this term (cited in Hashimi 2017).5 However, the Supreme Court has continued to insist on the distinction between those women approaching recognized authorities and those fleeing to the houses of strangers. When asked by international actors to clarify whether running away from domestic abuse was a crime, the court issued another instruction on the issue. It declared that the actions of those women who leave their homes to escape family violence and importantly, who immediately ‘go to the judiciary, law enforcement agencies, legal aid organizations or their relatives’ houses do not constitute a crime’ (cited in Hashimi, 2017:217). It also stated that those running away for the purpose of moral crimes should be prosecuted, but legal officials should not use the term ‘runaway’ for such cases (ibid).

Legal practices in Afghanistan clearly discriminate against women. An explicit government policy, as spelled out in the Supreme Court directive, states that women can be punished not only for actual sexual acts – the crime of zina – but also for simply abandoning or moving beyond spaces supervised by close relatives or state authorities. This policy must be understood as part of a broader patriarchal gender regime in which women’s bodies must be tightly monitored and placed under authorized surveillance (either by the family or the state), and where the chastity of women is given infinitively more importance than the chastity of men. As such, women’s scope for moral transgressions is much more limited than those of men.

Nonetheless, there is a noticeably lack of attention to the fate of men in debates and advocacy over moral crimes. Whilst there have been several reports on the number of women in jail for ‘moral crimes’, we know of no attempts to map the number of men charged with, or imprisoned, for the same crimes. In fact, even media reports on individual cases of women charged with moral crimes seldom report on the fate of their male partners, who might be facing jail sentences of up to 15 years.6

Below, we undertake an initial survey of when and how men might be prosecuted and convicted for consensual heterosexual acts under the Afghan legal system.7 We present Afghan government statistics indicating that the number of men imprisoned for moral crimes are in the hundreds, possibly even surpassing that of women. We discuss what we can and cannot conclude from these numbers, including from the statistics that actually suggest a considerable number of men are serving prison sentences specifically ‘for running away’ from home.

The law: men and consensual sexual crimes in Afghan criminal codes

The Afghan criminal code makes the act of zina – sexual intercourse between a man and a woman not married to each other – a criminal offense.8 Under the 1976 penal code, in force until February 2018, zina was punishable with between 5 and 15 years in prison. Afghanistan’s new penal code, currently in force,9 has reduced the maximum punishment to 5 years imprisonment.10 The zina provisions in both laws apply to both men and women equally, with no differentiation.

However, the question of exactly what constitutes ‘Afghan law’ is disputed. In the early 20th century, Afghan ruler King Amanullah, then presiding over one of the few sovereign Muslim countries in the world, consolidated a unique legal system based on a pioneering combination of Islamic fiqh and codified law (Ahmed 2017). Since then, the place of Islam in Afghan state law has been understood in radically different ways by the country’s legal scholars and practitioners. As mentioned above, article 130 in the Afghan Constitution permits the application of Hanafi fiqh in matters not covered by codified law.11 To more secular oriented legal officials, this article merely provides a small, supplementary and limited role for uncodified fiqh. To others, article 130 reflects an overall perspective on Afghan law as proceeding in its totality from divine sources– the Quran and the Sunnah, the saying and deeds of the Prophet. As such, the country’s written codes (qanon) are derived from fiqh,12 and at the same time they make up only a part of the overall applicable legal framework.13 It is based on this second view that the Afghan Supreme Court has officially and explicitly sanctioned the prosecution and imprisonment of women for ‘attempted zina’, even though ‘attempted zina’ is not defined as a crime in the penal code.14

The Supreme Court directive (Approval 572) was a response to human rights officials and others demanding an explanation for the many women they had found in Afghan prisons convicted for ‘running away.’ Our research suggests, however, that Afghan jails also contain men charged with or convicted for moral crimes, including ‘running away’ from home. In turn, this means that also when it comes to men, an assessment of applicable Afghan law regarding moral crimes would need to go beyond codified law, i.e. the penal code.

Finally, it should be added that in the 1976 penal code, in force until very recently, zina also referred to coerced scenarios (i.e. rape).15 In practice, therefore, men (and very rarely, women)16 could be charged with both ‘consensual’ and ‘coerced’ zina under the 1976 code. As discussed below, this significantly impacts the practical possibility of identifying the number of men incarcerated for consensual sexual crimes – since actual records might not differentiate between rape and consensual adultery. The 2018 penal code and a 2009 separate piece of legislation on violence against women clearly differentiate between rape (tajavoz-e jinsi) and consensual adultery, reserving the term zina for consensual acts only. However, the 2009 law has been applied selectively by prosecutors and judges, with many preferring to only apply the 1976 code (Wimpelmann 2017). Whether the new penal code will have a significant impact on the adjudication of moral crimes remains to be seen.

The numbers: Men in prison for moral crimes

Very little statistical data on criminal justice is readily available in Afghanistan. Although the Supreme Court collects records of individual court cases at all levels, it does not process or publish this in a form that provides information on conviction rates or detailed specification on types of crime. Neither are records specified by the gender of the offenders.17 Likewise, the Attorney General’s Office maintains individual file records, albeit in tabulated form, but does not publish statistical information related to moral crimes. A long running project intended to create an online database containing the status of all legal cases in the country apparently remains work in progress.18

We know of no published estimations of the numbers of men imprisoned for ‘moral crimes’ in Afghanistan.

This dearth of available statistics has been a major challenge to researchers and human rights workers who have sought information about women’s treatment in the Afghan justice system. They have had no option but to create their own datasets, through review and compilation of individual case files. Such undertakings could require months, if not years, of efforts by multiple-member research teams. For instance, when the Ministry of Women’s Affairs published an overview of the outcomes of registered cases of violence against women over a one year period, it was based on extensive research over several years (MOWA 2014). A 2012 research report on women’s imprisonment for moral crimes (HRW 2012) similarly found no statistics. To establish the grounds for the incarceration of women for moral crimes, Human Rights Watch researchers interviewed female prisoners (58 in total) in six different prisons and juvenile detention centers and when available, reviewed the women of girl’s individual records on file with the prison authorities and the prosecutor’s office.

When it comes to male prisoners and moral crimes, no corresponding undertakings appear to have been initiated. We know of no previously published estimations of the numbers of men imprisoned for ‘moral crimes’ in Afghanistan. The closest appears to be a 2008 UN report, which provides details on the number and legal grounds of imprisonment of juvenile boys – but not adult men (UNODC 2008). This report found that around 13 percent of all male juveniles were incarcerated for moral crimes19 – 52 boys. 35 female juveniles were incarcerated for the same crimes. The 2008 report notes that there is no data available for the legal grounds of the imprisonment of adult male inmates. Some ten years later, however, the Central Prisons Directorate under the Ministry of Interior provided our research team with data on men (and women) incarcerated for various moral crimes; categorized by the gender of the offenders and their place of incarceration (judicial custody and/or prison). The table below shows the number of male and female inmates (nationwide) in the Afghan prison system, as recorded by the Prisons Directorate in recent years, for the following moral crimes: adultery, running away from home and rape.

To our knowledge, the figures in Table 1 represent the first government data available about the number of adult men imprisoned for consensual sexual crimes in post-2001 Afghanistan. The figures are rather astonishing at first sight. Not only do they contradict commonly held assumptions that Afghan men commit sexual transgressions with impunity, they also suggest that men are incarcerated for moral crimes at a much higher rate than women. Nonetheless, these numbers must be treated with considerable caution.

Table 1: Men and women imprisoned for adultery, running away and rape

Firstly, given that zina is applied to both forced and consensual sexual acts, the figures of men imprisoned for zina are likely to include a considerable number of men who have been convicted for ‘forced’ zina – i.e. rape. Even some of the men imprisoned for ‘consensual’ zina are likely to have forced themselves upon their co-defendants, since legal aid providers and others have repeatedly found female rape victims to be imprisoned for adultery instead.

Secondly, the number of men imprisoned for zina also includes those arrested in police raids on brothels, a situation where coercion can also be said to feature, since many women are forced into prostitution. In such raids, the number of men present, and therefore arrested, are typically higher than the number of women, which may go some way in explaining the higher number of men imprisoned for zina compared to women.

Thirdly, it is possible that the gender of some of these people might simply have been wrongly recorded, so that some of those appearing as men in the records might actually be women.21

Most strikingly, the statistics we have obtained indicate that a large number of men are currently in prison for ‘running away’ from home (farar az manzel).

These caveats should not detract from the fact that the statistics on male inmates merits further investigation. The fact that the number of females imprisoned for zina and running away in the Prisons Directorate’s data is broadly consistent with the patterns documented over the years – between 300 and 600 at any one time– is a good-enough reason to take the Prison Directorate’s figures on male prisoners seriously. It should be added that female prisoners have often benefited from the Afghan state’s pardoning policies, for example female prisoners detained for moral crimes are regularly pardoned by the President during Eid. The practice of pardoning women and not men for moral crimes might partly explain the high number of men detained for consensual sexual moral crimes, as reflected in official records.

Most strikingly, the statistics we have obtained indicate that a large number of men are currently in prison for ‘running away’ from home (farar az manzel).22 For example, in the year 1395 (201623) 298 men and 90 women were in prison on this basis whereas in 1396 (2017) 239 men and 88 women were imprisoned. In both years, the number of men imprisoned for running away was more than three times those of women. Given that Afghan legal and judicial authorities have never publicly endorsed the prosecution of men for ‘running away’, we sought further clarifications from the relevant government authorities (specifically from the Attorney General’s Office) in order to better understand the legal grounds for the incarceration of men currently serving jail time for ‘running away’ from home. As a result of our inquires, the Attorney General’s Office has initiated a judicial review of the case files of the 25 male prisoners presently recorded as serving jail terms for running away in Kabul’s central prison.

Even at this stage, our conversations with legal officials and practitioners suggest that men are regularly prosecuted for running away —and more generally, that the practice is endorsed by many Afghan legal officials. In particular, many legal officials see it as problematic that Afghan codified law does not criminalize, or as they prefer to put it ‘is not very clear’ about the act of running away ‘in cases involving a married or engaged women’.24 Engagement has no status as a legally binding agreement in Afghanistan, and even married women do not violate any codified law in Afghanistan by ‘running away’, as long as the act of zina does not feature. But as mentioned previously, many legal officials hold the view that Afghan law in its totality cannot be reduced to its legal codes. Consequently, and based on the view that running away with a married or engaged women is a violation of Sharia, if not codified law, some legal officials report that they apply article 130 of the Constitution and charge both the woman and the man with running away.

It should be noted that whilst women are also deemed to be committing a crime when they run away on their own, men are said to be running away only when they run away with a woman. But even if the basis for men’s incrimination in cases of running away is narrower, it nevertheless appears to occur frequently. Indeed, it has been specifically suggested that in cases involving the running away of an engaged or married woman, her male co-eloper is considered a ‘partner in crime’ and as such liable for prosecution by the state.25

The men convicted for actual zina also deserve further attention. Previous research and media reports suggest that numerous men are convicted of zina in the context of elopement. These are cases where a man and a woman have eloped with the intention of getting married. Often, the woman is already engaged to another man, sometimes with the unwanted marriage imminent. In other cases, the parents of the woman have been unwilling to agree to a match proposed by their daughter, upon which the woman runs away with the man of her choice. Whatever the case, Afghan codified law recognizes the right of men and women of majority age to marry without a guardian’s permission, and explicitly states that ‘carrying away a women for the purpose of marriage’ is not a crime (Article 425/ 599 in the 1976 and 2018 Penal Codes respectively).

Despite these legal guarantees, eloped couples often face numerous hurdles to getting married, which in turn might lead to charges of zina: local mullahs might refuse to perform the nikah (marriage rites) of an eloped couple. Our research also shows that even courts in Kabul might create extra-legal obstacles to eloped couples wanting to marry, such as consent of parents, proof of virginity (from women), proof of identity (a tazkira can only be issued on the basis of the father’s tazkira, thus requiring his consent), affidavits from witnesses, or reconciliation between the two families before a nikah can be officiated by a judge in the family court. Men (and women) might also find themselves convicted for zina based on flawed or circumstantial evidence. If a hymen examination, routinely forced upon eloped women,26 is held to show that an unmarried woman is not virgin, both parties might be charged with, and convicted of zina. Some judges are also inclined to rule that any unmarried couple who have spent time in privacy are guilty of adultery.

Preliminary Conclusions

The debate on moral crimes prosecutions in Afghanistan has almost exclusively focused on women, but as researchers have long argued, patriarchal gender orders also marginalize certain men (Cornwall and Lindisfarne 1994; Connell 1995). In the kinds of scenarios discussed in this paper, men – typically poor, young and lower status – feature as victims of patriarchal gender relations alongside their female partners. Like their female counterparts, many men are imprisoned for consensual zina, and – as it appears – merely for running away. It is certainly the case that women are, as a gender, more vulnerable to moral crimes charges, and they generally face more severe repercussions – both socially and legally. However, the disproportionate impact on women should not justify complete disregard for the plight of their male counterparts.

At the time of writing, we await further numbers and investigations on this issue, including verified statistical data from the Attorney General’s Office and the result of their internal investigation regarding 25 men currently held in Kabul’s central prison for ‘running away’. However, the numbers obtained from the Central Prisons Directorate, as well as other preliminary investigations strongly suggest that more focus on the incarceration of men for moral crimes is warranted. Admittedly, with the overall legal system in Afghanistan displaying severe weaknesses, the hundreds of men imprisoned for moral crimes are only a fraction of the male prison population, estimated at around 25,000. Many other of these 25,000 inmates might have also suffered unjust treatment in the courts. From this perspective, it might seem unfair to single out for attention only those men who are incarcerated specifically for (heterosexual) moral crimes.

However, if the starting point is to problematize the Afghan state’s prosecution of consensual relations outside of marriage, then the complete exclusion of men from the picture seems a glaring omission. The relative attention and support provided to women incarcerated for moral crimes has brought about real positive effects. The yearly rounds of presidential pardons have included significant numbers of women convicted for moral crimes. Women charged with moral crimes have also been more or less guaranteed free legal representation in recent years (Day and Rahbari 2017).

From this perspective, it only seems reasonable to ask how many men are in fact jailed for adultery and running away. The data presented in this brief represents a first and initial attempt to answer this question. It indicates that hundreds of Afghan men are currently in prison for consensual (hetero) sexual relations, including running away. More comprehensive research is needed to uncover the legal grounds for their imprisonment and to better understand how many men have been affected by the Afghan state’s prosecution of moral crimes.

A first step would be the release of the results of the Attorney General’s Office’s investigation regarding imprisonment of the 25 men for ‘running away’ in Kabul’s central prison. Moreover, similar investigations should be undertaken across all the provinces in Afghanistan. We also welcome the release of the Case Management System data on men’s prosecution and imprisonment for moral crimes. However, establishing a comprehensive, detailed picture of men’s imprisonment for moral crimes would require in depth studies of a substantial number of individual cases, including men convicted for zina as well as ‘running away’. In other words, efforts similar to those already undertaken over the Afghan state’s punitive actions against women for ‘moral crimes’.

Notes

1 The research upon which this paper is based forms part of the research project New Afghan Men? Marriage, Masculinities and Sexual Politics in Contemporary Afghanistan, funded by the Research Council of Norway (grant 249707), carried out by Peace Training and Research Organization and Chr. Michelsen Institute. We want to thank Masooma Sa’adat for her tireless, persistent and skillful research assistance. We also want to thank Deniz Kandiyoti, Magnus Marsden and Siavash Rahbari for helpful comments on an earlier version of this paper.

2 The phrase ‘escaping from the house’ is a more accurate translation of the Dari term farar az manzel. However, since the term ‘running away’ has so far been used in English language discussions about the topic, we have chosen to use this latter term.

3 In Muslim-majority countries, the basis of law has historically been the will of God, and fiqh refers to the methodology of ascertaining legal conclusions from divine sources (the Quran and the Sunnah- sayings and deeds of the Prophet). Sharia, whilst sometimes used interchangeably with fiqh, refers to rules of God and thus includes a broader domain of life, such as fasting and praying (see Wimpelmann, 2017, 182).

4 High Council of Supreme Court Approval #572, dated 24 August 2010.

5 Hashimi argues that the AGO directive is open to misuse because it adds ”other circumstances where people runaway to commit any other crime is not covered [by this directive]” (2017: 217).

6 ‘Moral crimes’ (jarayem-e akhlaqi) might also refer to other, non-sexual acts deemed contrary to public moral and religion, such as drinking and gambling. In fact, government records sometimes include these acts under the rubric of moral crimes. In this paper, we use the term moral crimes to refer to sexual crimes only. Also, we only cover heterosexual crimes.

7 Men are also charged with and convicted of lawat (sodomy). The prosecution of homosexual acts in the Afghan justice system is beyond the scope of this study, but it is certainly a question meriting further research.

8 In classical Islamic jurisprudence, zina is one of several crimes of Hudood. The definition, punishment and evidentiary requirements of Hudood crimes are derived from holy sources (the Quran and the Sunnah- the sayings and deeds attributed to the Prophet). As such, Hudood crimes are invested with special religious significance, and to formally abolish Hudood would represent a secularization of law. Hudood punishments are formally recognized in the current Afghan Penal Code (Article 2 (2) but largely not enforced in practice. The Hudood punishment for zina is stoning to death if the perpetrator is married, and lashing if he or she is not.

9 The new penal code (as the previous one) has been enacted as a presidential decree and must be submitted to the parliament for ratification.

10 Both the old and the new penal codes also explicitly recognize the Hudood punishment for zina (Article 643 (2) in the 2018 code and article 426 in the 1976 code) - but without spelling out these punishments.

11 Article 130 reads: “In cases under consideration, the courts shall apply provisions of this Constitution as well as other laws. If there is no provision in the Constitution or other laws about a case, the courts shall, in pursuance of Hanafi jurisprudence, and, within the limits set by this Constitution, rule in a way that attains justice in the best manner.”

12 See footnote 3.

13 For a (rare) analysis of the early development of Afghanistan’s rather unique combination of codified law and Sharia, see (Ahmed 2017).

14 Approval 572, dated 24 August 2010 (1389/6/2), High Council of Supreme Court of Afghanistan. Some would argue that the enactment of the new penal code in February 2018 renders this advisory directive null and void, since the new penal code supersedes the directive.

15 The definition of all sexual intercourse (whether consensual and coercive) out of wedlock as the crime of ‘zina’ is in line with classical understandings of Islamic law (Azam 2015). The 1976 penal code therefore signals adherence to Islamic jurisprudence. For the same reason, despite the establishment of rape as a distinct crime in the 2009 EVAW law, many prosecutors and judges still prefer to use the word zina to refer to rape, sometimes (but not always) applying the term ‘forced zina’ (zina bil jabr). However, reading the 1976 penal code’s provisions on zina (articles 425-429) one is inclined to conclude that these were written mainly with rape in mind, since the articles formulate a number of aggravating factors applicable to rape scenarios. Most likely, the term zina was inserted as a late compromise to placate more conservative groups who wanted a stricter adherence to classical fiqh. Indeed, (Samandary 2014) suggests that the initial text of the law used ‘rape’ and that zina only appeared in a later version . Whatever the case, the articles have in practice been used to adjudicate both consensual zina and rape.

16 As abettors to the crime.

17 Upon our request, the Supreme Court made available the following figures; in 1394 there were 3520 convictions for moral crimes and 451 convictions for rape (tajavoz-e jinsi). The corresponding numbers for 1395 were 2197 and 285 respectively. There were no further specifications of the type of offenses contained in the moral crime category or information about the offenders’ gender.

18 We have been informed by AGO that the Case Management System (CMS) database, currently operated by a private international contractor contain technical errors that needs to be corrected before we can access data about the prosecution of men for moral crimes. One example we were given relates to the gender specification of offenders; the gender of some of the female offenders had been wrongly recorded as male.

19 The figure is believed to include an unspecified number of boys convicted of lawat (sodomy). The authors note that these boys might in reality have been raped.

20 The Afghan year 1394 corresponds to 21 March 2015-20 March 2016, 1395 corresponds to 21 March 2016-20 March 2017 and so on.

21 It appears that this error has occurred at a large scale in the Case Management System (CMS), an online database set up by donors to provide up to date information on the status of all legal cases in the country. The CMS is designed to collect and centrally process case information from all the different judicial organs, including the Supreme Court, Attorney General’s Office, Ministry of Justice and Ministry of Interior. The default gender category in the CMS is male and those entering data might have failed to change the gender to female in many cases. AGO staff compiling data from the CMS found up to 140 cases of ‘running away’ where it appeared that women had incorrectly been recorded as men. Our request for access to the data on moral crimes in the Case Management System has been put on hold by the Attorney General’s Office following the discovery of this mistake. We have been informed that we will receive new data from AGO once the technical errors had been rectified. At the time of writing it is unclear when the process of reviewing and correcting the data in the CMS will be finalized and how soon after we might get access to this data.

22 The Attorney General’s Office claims to have ceased prosecutions for running away in 1395 (2016). We have not seen any instructions issued by the AGO to that effect. Neither have we been able to access data that would verify this claim, such as details of indictments and convictions by year. The statistics from the Prisons Directorate simply provides the number of inmates currently imprisoned for running away at any one time, it does not tell us anything about the year of conviction.

23 See footnote 20.

24 Interviews with legal officials and lawyers in Kabul, autumn 2017.

25 Personal communication by a member of the research team with a group of prosecutors in the Attorney General’s Office in Kabul, 11 December 2017.

26 Following pressure from human rights activists, Article 640 of the new penal code lists virginity tests without the women’s consent or the order of an authorized court a sexual assault, punishable by short term imprisonment.

References

Ahmed, F. (2017). Afghanistan Rising. Islamic Law and Statecraft between the Ottoman and British Empires. Cambridge/ London, Harvard University Press.

Azam, H. (2015). Sexual Violation in Islamic Law: Substance, Evidence, and Procedure. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Connell, R. W. (1995). Masculinities. Cambridge,UK, Polity.

Cornwall, A. and N. Lindisfarne, Eds. (1994). Dislocating Masculinities: Comparative Ethnographies. London, Routledge.

Day, D. and S. Rahbari (2017). Legal Aid Assessment and Roadmap (LAAR). Kabul, Asia Foundation: 1-256.

Hashimi, G. (2017). ”Defending the Principle of Legality in Afghanistan: Towards a Unified Interpretation of Article 130 to the Afghan Constitution.” Oregon Review of International Law 18(185): 185-226.

Human Rights Watch (2013) ”Afghanistan: Surge in Women Jailed for ‘Moral Crimes’. Prosecute Abusers, Not Women Fleeing Abuse.”

Human Rights Watch (2016) ”Afghanistan: End ‘Moral Crimes’ Charges, ‘Virginity’ Tests

President Ghani Should Honor Pledge not to Arrest Women Fleeing Abuse.”

MOWA (2014). First Report on the Implementation of the Elimination of Violence against Women ( EVAW) Law in Afghanistan Kabul, Islamic Republic of Afghanistan, Ministry of Women’s Affairs.

Samandary, W. (2014). Shame and Impunity: Is violence against women becoming more brutal? Kabul, Afghan Analyst Network.

UNODC (2008). Afghanistan. Implementing Alternatives to Imprisonment, in line with International Standards and National Legislation. Assessment Report. Vienna/ New York, United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime: 1-101

Wimpelmann, T. (2017). The Pitfalls of Protection: Gender, Violence, and Power in Afghanistan. California: University of California Press.